Rolling His Jolly Tub: Composer Elliott Carter, St. John’s College Tutor, 1940-1942

Hollis Thoms

[This account of Elliott Carter’s time as a Tutor at St. John’s College, 1940-1942, was originally published in The St. John’s Review 53, no. 2 (Spring 2012). The editors are grateful to Susan R. Paalman, Dean of St. John's College Annapolis, for permission to reprint it here.]

Elliott Carter at St. John’s College

Tutor, 1940-1942

Away went he out of town towards a little hill or promontory of Corinth called (the) Cranie; and there on the strand, a pretty level place, did he roll his jolly tub, which served him for a house to shelter him from the injuries of the weather.

—Rabelais

[ 1 ] Elliott Carter, now one of America’s foremost living composers, was a Tutor at St. John’s College from 1940 to 1942. This was a turbulent time both for the College and for Carter. The College was still in the process of phasing out the “old” curriculum and was trying to establish the “new” Great Books curriculum. Then, just after the last students under the old regime were graduated in 1941, World War II began to coopt college-age men for the war effort. In Carter’s life, his recent marriage, together with the lingering effects of Great Depression, made it imperative for him to secure an academic position. At the same time, he was transforming his compositional practice, casting off traditional influences, and moving in a radically new musical direction. The story of Carter’s time at St. John’s is the story of two interlaced experiments: the College’s experiment in higher education, and Carter’s experiment in finding his vocation as a composer.

Elliott Carter, 1908-1940

[ 2 ] Elliott Cook Carter, Jr. was born in New York on December 11, 1908 to lace-import businessman Elliott Cook Carter, Sr. and his wife Florence, née Chambers. The young Elliott was intended to succeed his father at the lace-import firm. As he grew, however, his musical talents and interests led him away from business and toward a career in music. The elder Carter was openly contemptuous of such an impractical scheme (Wierzbicki 2011, 5-6). But Clifton J. Furness, music teacher at the Horace Mann School where Carter studied from 1920 to 1926, recognized and encouraged his student's talent. He took the teenage Carter to avant-garde concerts, exposing him to new music by composers such as Bartók, Ruggles, Stravinsky, Varèse, Schoenberg, and Webern. And he introduced him to many New York musicians and composers, including Charles Ives, the eccentric millionaire businessman and experimental composer. Ives often invited Carter to join him and his wife in their Carnegie Hall box for performances by the Boston Symphony, which, under the leadership of Serge Koussevitzky, commissioned many new works by living composers. Ives became a musical and intellectual role model for Carter.(1)Wierzbicki 2011, 7-9.

[ 3 ] The distance between the younger Carter’s ambitions and his father’s continued to grow during these years. When Carter was sixteen in 1925, his father took him along on a business trip to Vienna, where all his attention was focused on trying to acquire all the currently available scores of Schoenberg and Webern. Carter remembers going with his father to a performance of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, which the father summed up with “Only a madman could have written anything like that.” Yet that performance was one of the experiences that inspired the young Elliott to become a composer.(2)Edwards 1971, 40, 45.

[ 4 ] So, contrary to his father’s wishes, Carter decided to study music at Harvard. Ives wrote a letter of reference in which he pointed to Carter’s artistic instincts:

Carter strikes me as rather an exceptional boy. He has an instinctive interest in literature and especially music that is somewhat unusual. He writes well—an essay in his school paper—“Symbolism in Art”— shows an interesting mind. I don’t know him intimately, but his teacher in Horace Mann School, Mr. Clifton J. Furness, and a friend of mine, always speaks well of him—that he’s a good character and does well in his studies. I am sure his reliability, industry, and sense of honour are what they should be—also his sense of humor which you do not ask me about.(3)Schiff 1983, 15-16.

[ 5 ] He intended to major in music at Harvard in the fall of 1926, but lasted only a semester in that program. He remained at Harvard, however, but opted to spend his undergraduate years working on a degree in English literature. The Harvard music department was not to his liking, since it would have nothing to do with the new music in which Carter was interested. Carter said that he “would have been glad if somebody at Harvard had explained to me what went on in the music of Stravinsky, Bartók and Schoenberg, and had tried somehow to develop in me the sense of harmony and counterpoint that these composers had.”(4)Wierzbicki 2011, 11.

[ 6 ] Carter enjoyed his English literature experience, but, as with music, he went further than the traditional literature offerings, which stopped with reading Tennyson. He preferred reading more avant-garde authors such as Gerard Manley Hopkins, William Carlos Williams, Marianne Moore, T. S. Elliot, e. e. cummings, James Joyce, D. H. Lawrence, Gertrude Stein, and others. In addition to studying classics, philosophy, and mathematics, he also studied German and Greek—which, in addition to his fluency in French, made him quite proficient in languages. Carter spent his undergraduate years pursuing the broadest possible education, for he saw music not merely as a technical study, but as an art form embedded in and intimately connected with the liberal arts. He, did, nonetheless, participate in more traditional musical activities during his time at Harvard, taking instruction in piano, oboe, and solfeggio at the Longy School. He sang tenor in the Harvard Glee Club and in a Bach Cantata Club. He also spent time studying the scores of the past masters, taking full advantage of the vast holdings of the Harvard music library.(5)Wierzbicki 2011, 15-19.

[ 7 ] Carter’s youthful interest in the new music can be seen in the repertory of works he performed with his old music teacher Clifton Furness in a joint piano recital in Hartford, Connecticut on December 12, 1928: the program included pieces by Igor Stravinsky, Darius Milhaud, Arnold Schoenberg, Francis Poulenc, Alfredo Casella, Gian Francesco Malipiero, Henry Gilbert, Charles Ives, Eric Satie, Paul Hindemith, and George Antheil.(6)Schiff 1983, 15.

[ 8 ] After Carter graduated, he went on receive an MA in musical composition at Harvard, because, when Gustav Holst came as a visiting composer and Walter Piston returned from studying in Paris, there was a new interest in contemporary music at Harvard, so that Carter felt more at home in the altered the musical environment. Piston recommended that Carter go to study with the well-known teacher of composition Nadia Boulanger at the École Normale de Musique de Paris, and Carter did so from 1932-1935. Carter’s fluency in French made Paris a natural choice; and because both Piston and Aaron Copland, whom Carter knew and admired, had studied with her, he felt that it was a reasonable thing to do.(7)Wierzbicki 2011, 20-21.

[ 9 ] Despite persistent financial worries while in Paris — his father did not approve of the plan and cut his allowance in half, though his mother continued to supplement the allowance — Carter thrived as a student of Boulanger, whom he remembers with admiration for the way she illuminated both the past and the future of music:

The things that were most remarkable and wonderful about her were her extreme concern for the material of music and her acute awareness of its many phases and possibilities. I must say that, though I had taken harmony and counterpoint at Harvard and thought I knew all about these subjects, nevertheless, when Nadia Boulanger put me back on tonic and dominant chords in half notes, I found to my surprise that I learned all kinds of things I’d never thought before. Every one of her lessons became very illuminating. . . . Mlle. Boulanger was a very inspiring teacher of counterpoint and made it such a passionate concern that all this older music constantly fed me thoughts and ideas. All the ways you could make the voices cross and combine or sing antithetical lines were things we were involved in strict counterpoint, which I did for three years with her—up to twelve parts, canons, invertible counterpoint, and double choruses—and found it fascinating.”(8)Edwards 1971, 50, 55. Emphasis added.

Then also, when I was studying with Mlle. Boulanger I began for the first time to get an intellectual grasp of what went on technically in modern works. I was there at a time when Stravinsky, who was of course the contemporary composer she always admired most [was also in Paris]. . . . The way she illuminated the details of these works was just extraordinary to me. . . . I met Stravinsky, because he used to come to tea at Mlle. Boulanger’s. . . . [W]hat always struck me every time I heard Stravinsky play the piano—the composer’s extraordinary, electric sense of rhythm and incisiveness of touch that made every note he played a “Stravinsky-note” full of energy, excitement and serious intentness.”(9)Edwards 1971, 51, 56. Emphasis added.

[ 10 ] Boulanger’s attitude toward music matched his own: in his daily lessons, composition as a craft was combined with composition as in the context of the liberal arts. Carter spent three years studying with Boulanger, and as a result of her tutelage, he gained both the musical craftsmanship and the self-confidence to produce compositions that he considered worth preserving. It was only “after Paris” that Carter “could begin to compose.”(10)Wierzbicki 2011, 24.

[ 11 ] After his return from Paris, Carter immersed himself in musical activities, groups, and composing, first in Boston and then in New York. He wrote a number of choral works including one called “Let’s Be Gay,” a work for women’s chorus and two pianos based on texts by John Gay. It was written for, and performed by, the Wells College Glee Club in the spring of 1938, which was led by his friend Nicolas Nabokov, who was to figure again in Carter’s career a few years later.(11)Wierzbicki 2011, 25.

[ 12 ] The Great Depression made it impossible for Carter to find a secure job, but he was able to become a regular contributor to Modern Music, a journal that had been founded in 1924 as the house organ of the New York-based League of Composers. In the process of writing thirty-one articles and reviews for the journal, he gained familiarity with current compositional activity in New York, and he developed the skills of a professional music critic.(12)Wierzbicki 2011, 26-27.

[ 13 ] In addition, he was hired as a composer-in-residence for the experimental ballet company Ballet Caravan, formed in 1936 by Lincoln Kirstein, whom Carter had met in Paris. In that same year, Carter wrote the piano score of a ballet for the company, called Pocahontas, which premiered in 1939. In June of 1940 the New York Times announced that an orchestral suite drawn from the ballet had won “the Julliard School’s annual competition for the publication of orchestral works by American composers.” This prestigious award finally launched Carter’s career as a composer at the age of 31.(13)Wierzbicki 2011, 27.

[ 14 ] Shortly before the premiere of Pocahontas, on July 6, 1939, Carter married Helen Frost-Jones, a sculptor and art critic, whom he met through his friend Nicolas Nabokov. With the possibility of a family now on the horizon, Carter redoubled his efforts to find employment. At Aaron Copland’s suggestion, he applied in the spring of 1940 for a teaching position at Cornell University. Cornell was actively considering him, but the school was not in a hurry to hire. Carter, on the other hand, wanted a position for the fall. So instead he accepted an offer to teach music, mathematics, physics, philosophy, and Greek at St. John’s College in Annapolis.(14)Wierzbicki 2011, 28.

[ 15 ] The offer from St. John’s was also due to Carter’s friend Nicolas Nabokov, who recommended Carter after himself turning down the offer of a position for 1940-1941. In a letter to Stringfellow Barr dated June 22, 1940, Nabokov explained, first, that he could not accept the position for that year because his wife was expecting a child and, since they lived in Massachusetts, it would be too inconvenient to move or to commute between the arduous new job and his family; second, that the compensation offered at St. John’s College was not adequate for him to take care of his new family; and third, that he could not in good conscience leave Wells so soon before the beginning of the fall term.

[ 16 ] In declining the position, Nabokov recommended a substitute: “Mr. Elliott Carter of whom I spoke to you the other day and more extensively to Mr. Buchanan would in my opinion fit perfectly into the St. John’s place of education. . . . Mr. Carter as you will see from his curriculum vitae and the enclosed articles is a very thorough, serious and reliable man and I recommend him to you very highly. . . . [H]e is very anxious to undertake the job.” He suggested that Carter could substitute for him during the coming school year, and then Nabokov himself would come to St. John’s the following year. Nabokov did indeed arrive at St. John’s the following fall to take over the teaching of music; but Carter did not leave. Instead he spent a second year at St. John’s teaching Greek, mathematics, and seminar.(15)Nabokov 1940.

[ 17 ] Carter’s decision to accept the position at St. John’s could not have been easy to make. He was just beginning his career as a composer, trying to develop a distinctive creative voice in challenging financial circumstances, which were made even more challenging by his recent marriage. This was certainly a turbulent time in his life.

[ 18 ] He was to join the St. John’s community at a turbulent time in its own history. The college had recently launched an educational experiment unprecedented in American higher education, the success of which was far from certain. The prospect of teaching at the third oldest college in the nation (the direct predecessor of St. John’s, King William’s School, was founded in 1696, after Harvard in 1636 and William and Mary in 1693) might have seemed a more stable position than anything the young composer could find in New York, but he would soon discover a great deal of unstable dissonance in the community he was to join.

St. John’s College in 1940: Turbulence

[ 19 ] In 1937, St. John’s College found itself at a crossroads. In addition to a severe financial crisis, the physical plant was in deep disrepair. A weak Board of Governors and Visitors had appointed three new Presidents within nine years in an attempt to find someone who could remedy the situation. All three had failed, however, and the College had lost its accreditation status with the Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools. Demoralized faculty members were leaving.(16)See Murphy 1996 and Rule 2009 for the facts in this section.

[ 20 ] The stronger members of the Board decided to take drastic action. They named Robert Hutchins, President of the University of Chicago, who had long been involved in attempts to revive the liberal arts, to chair the Board. The Board also hired two colleagues of Hutchins’ from the Committee on Liberal Arts at Chicago as President and Dean, Stringfellow Barr and Scott Buchanan. Their charge was to effect a complete transformation from a traditional college curriculum to a radically “old” Great Books curriculum. There would no longer be the traditional options leading to specialized degrees; the faculty would no longer teach only in their areas of expertise, but in all areas of the curriculum; the college would no longer participate in intercollegiate sports; there would no longer be fraternities on campus.

[ 21 ] Instead, the completely renovated curriculum, known as the “New Program,” consisted of two seminars (discussion groups) per week on one of the books on the prescribed reading list, five tutorials (small classes) per week in mathematics, five language tutorials per week, at least one three-hour laboratory period per week, and at least one formal lecture per week.(17)Barr 1941, 44.

[ 22 ] In order to effect the change, the New Program was phased in over a four-year period. Students entering in the fall of 1937 were allowed to choose which curriculum they would pursue. Thereafter, all incoming freshmen entered the New Program. Carter arrived in the 1940-1941 school year, the last year of the unsettled transitional period, at the end of which the last graduates under the old curriculum were awarded their degrees alongside the first graduates under the New Program. By Carter’s second year, 1941-1942, the New Program had completely replaced the old curriculum.

[ 23 ] Clearly, the board was taking a risk by instituting such an innovative and untried curriculum, and the risk paid off slowly. On 1937 there were twenty freshmen who entered in the New Program; in 1938, forty-six; in 1939, fifty-four; and in 1940, when Carter arrived, there were ninety-three. The total number of students held steady at around 170 during the first four years, so the transition seemed relatively painless from the enrollment point of view. But the exodus of faculty members continued, since quite a few were not prepared to give up their specialties to become co-learners along with their students in an environment of cooperative learning in all the liberal arts.

[ 24 ] In his quarterly report to the board of April 1939, Stringfellow Barr described the sort of student and the sort of tutor that would thrive in the New Program. The students would have to be able to think clearly and imaginatively, read the most diverse sorts of material with understanding and delight, distinguish sharply between what he knows and what is mere opinion, have an affinity for first-rate authors and an aversion to second-rate authors, derive great pleasure from exercising his intellect on difficult problems, and desire to be a thoughtful generalist rather than a highly proficient specialist. The tutors, on the other hand, would have to transcend divergent intellectual backgrounds, be clear expositors, imaginative artists, and cooperative fellow seekers, know how to teach and learn through discussion, and, above all, be intellectual treasure-hunters.

For unquestionably, the treasures our authors had written were for our generation partially buried. We needed men who wanted to help our students dig them up. The best that we could do, the best indeed that could be done, was to call for volunteers, volunteers for the treasure hunt, remembering for our comfort that this treasure hunt has never wholly ceased during the intellectual history of our Western civilization.(18)Nelson 1997, 52-59.

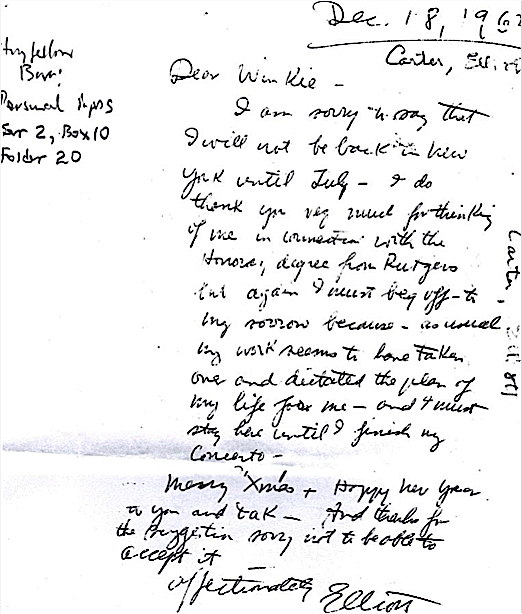

[ 25 ] When Stringfellow Barr and Scott Buchanan recruited Elliott Carter they were looking for a “treasure hunter.” They found in him a kindred spirit who transcended intellectual narrowness, thought clearly, and was an imaginative artist. Their relationship continued long after all of them had left St. John’s. Years later, in 1962, when Barr was invited to nominate Elliott Carter for an honorary degree at Rutgers University, Carter replied from Rome in a letter that testifies to their enduring friendship. (Barr was affectionately called “Winkie” by his close friends.)(19)Carter, 1962.

Dec. 18, 1962Dear Winkie —

I am sorry to say that I will not be back in New York until July — I do thank you very much for thinking of me in connection with the honorary degree from Rutgers but again I must beg off — to my sorrow — because as usual my work seems to have taken over and dictated the plan of my life for me — and I must stay here until I finish my Concerto — Merry Xmas and Happy New Year to you and Tak [?] — And thanks for the suggestion Sorry not to be able to accept it —

Affectionately, Elliott

Fig. 1

Letter to Scott Buchanan (St. John’s College Library Archive, Barr Personal Papers, Series 2, Box 10, folder 20)

1940-1941: Tutor and Director of Music

[ 26 ] In the college catalogue of 1940-41, Carter was listed as Tutor and Director of Music.(20)St. John’s College Catalogue 1940-41. His responsibilities included supervision of the entire music program. According to the college newspaper, The Collegian, which ran a long article in October about the upcoming year’s music program, Carter would plan and schedule a series of six concerts by visiting artists; he would give a lecture the week before each concert to discuss the works on the program; he would organize and direct student instrumental ensembles to appear in recitals and accompany the Glee Club; he would conduct the Glee Club, which was to rehearse three times per week and give numerous recitals during the year; he would lead a music discussion group on Saturday mornings for interested students; he would lead a counterpoint, harmony, and composition class for interested students; he would supervise concerts of recorded music four times per week; he would prepare the music room in the late afternoon each day for students to listen to recorded music.(21)The Collegian, Oct. 19, 1940.

[ 27 ] Carter seems to have taken to these duties enthusiastically, if the pictures in the 1941 St. John’s College Yearbook give any indication. In the faculty section of the yearbook there is a picture of Carter working assiduously at his desk, and in the Glee Club section there is a photo of him directing the singers with deliberation. The yearbook also provides a positive evaluation of Carter’s work with the Glee Club over the year:

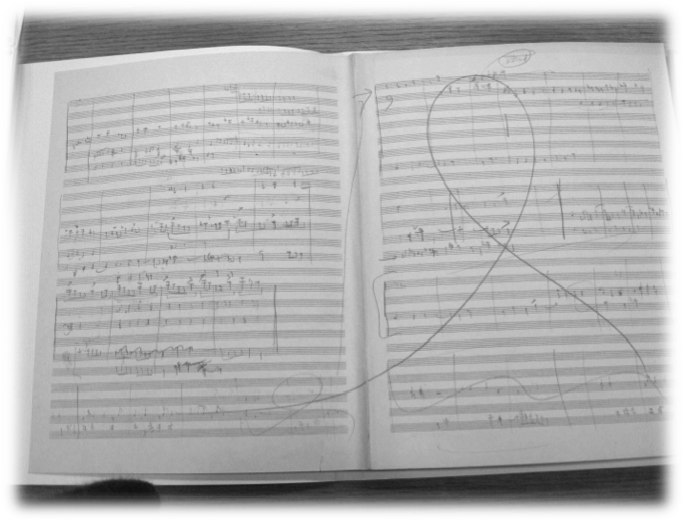

The aims of the Club are primarily to foster competent group singing (not necessarily concert competency), to gain a better understanding of choral music, and . . . to let the ear hear what the voice does. To date the criticisms received from the two mid-winter recitals give encouragement to the feeling that the Glee Club is headed in the right direction. Studies, scholarship work, and talents turned toward other interests have naturally taken their toll of the initial roster, but there still remains a group large enough to work with the music under consideration. The members are from the three lower classes, which means that their return next fall will leave only the task of inducting freshmen and learning new songs; this is indeed a strong incentive for the club’s continuation and success.(22)St. John’s College Yearbook, 1941, 30.

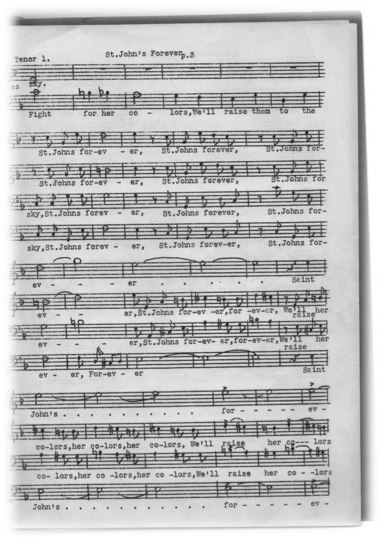

Fig. 2

Carter’s four-part setting of “St. John’s Forever”

[ 28 ] And the work Carter did with the music program was indeed quite varied. For instance, on Saturday, December 20, 1940, the Glee Club performed, at the request of Scott Buchanan, on the St. John’s College monthly radio broadcast from WFBR in Baltimore. On that occasion they sang “St. John’s Forever,” arranged especially by Carter for the broadcast. (A copy of this arrangement can be found in the St. John’s College Music Library.) They also sang at “Miss Alexander’s Christmas Party” on December 18. And Carter assisted in making the musical arrangements for the end-of-term variety show That’s Your Problem, which showcased the vaudeville talents of both students and tutors.(23)The Collegian, Nov. 13 and Dec. 13, 1940.

[ 29 ] When the first performance of the year’s concert series was announced, The Collegian took the opportunity to explain the purpose of the lectures that Carter would give in preparation for each concert:

While Mr. Carter plans to discuss primarily the program for each concert, the entire lecture series will form a course in music appreciation. As Mr. Carter is himself a talented musician, the course affords a unique opportunity in musical education.(24)The Collegian, Nov. 1, 1940.

The Collegian also reviewed each concert, and while the performances were sometimes panned, sometimes praised, there was no criticism of Carter’s work in organizing the series and lecturing on the pieces performed.

[ 30 ] Things went less swimmingly with some of Carter’s other duties. The counterpoint, harmony, and composition class that had been announced in October was “on the verge of collapse” at the start of the second term because of waning attendance. The Saturday morning music discussion class was considered to be “somewhat irregular”; nevertheless, in January the group had just finished an analysis of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, and was starting to study Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations.(25)The Collegian, Jan. 31, 1941. In February it was announced that, “at the request of a small group of students,” Carter would be offering a new class in ear training and sight-singing on Saturday mornings.(26)The Collegian, Feb. 14, 1941.

[ 31 ] Taking into account the addition of this new class, Carter’s teaching schedule for his first year at St. John’s looked like this:

Elliott Carter's Teaching Schedule, 1940-41

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday | |

| 10-12 | Music discussion and ear training | ||||||

| 2-3 | Counterpoint | Counterpoint | |||||

| 4-6 | Music Room | Music Room | Music Room | Music Room | Music Room | Music Room | |

| 6-7 | |||||||

| 7-8 | Recorded Music | Glee Club | Recorded Music | Glee Club | Glee Club | Recorded Music |

[ 32 ] In addition to his teaching hours, it seems that Carter was responsible for writing several manuals relating to musical studies during the fall 1940 term. Not surprisingly, he authored a “Manual of Musical Notation” explaining how to read and write music, which was no doubt intended for the use of students in his various music classes. But his name is also attached to several manuals of musical studies that were part of the Freshman Laboratory curriculum: “Musical Intervals and Scales,” “The Greek Diatonic Scale,” and “The Just Scale and Its Uses.”(27)Schiff 1983, 336. Another manual exists for a fourth laboratory unit called “The Keys in Music,” which, though unsigned, must also have been devised by Carter, because the musical examples are written in his distinctive musical script. (All the documents mentioned in this paragraph can be found in the St. John’s College Library Archives.)

[ 33 ] All these manuals demonstrate Carter’s understanding of the integration of music with the rest of the curriculum of the New Program. The “Manual of Music Notation,” for instance, likens music to language, and musical notation to linguistic writing systems.

Musical notation is the method used to represent graphically the patterns of sound which are the basis of music. Like the writing which represents the language of words, it serves man to overcome his lapses of memory by maintaining a more permanent record and aids him in the transmission to other men of the work of his mind as well in art as in thought. The simplest kind of notation of music sounds indicates in a general way the prolongation or shortening of the vowels of words and also the rise and fall of the voice while it is sounding them.(28)Carter 1941, 1.

[ 34 ] The comparison between music and language was a favorite notion of Scott Buchanan’s, and Carter seems to have agreed with him. It is likely that the two discussed the matter before Carter wrote this manual. There is a record from this period of Buchanan’s thoughts on music—a three-page outline of the topic “Music” dated November 8, 1940 that shows clear parallels to Carter’s formulation. The first page of the outline contains these notes:(29)Buchanan 1940, 1.

|

Voice—noise

Measurement and Words Verbal Analogies |

It appears that the two men were in agreement that music is one of the writing and reading disciplines in the liberal arts tradition, and that this view needed to be expressed somehow in the New Program.

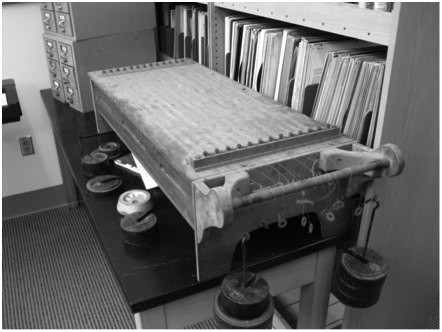

[ 35 ] If Carter’s music-notation manual links the study of music to the study of language, his laboratory manuals even more clearly link it to the study of mathematics and physics. In 1939-1940, the year before Carter’s revision of the music element in the laboratory program, there was only one music laboratory exercise during the entire year, and the text of the manual for that exercise was a mere five pages that described the design of a simple, two-string sonometer (sounding board), gave instructions for duplicating Pythagoras’ experiments on musical ratios, provided directions for creating various musical scales, and posing questions to be answered in laboratory reports. Carter’s four laboratory units brought the total number of manual pages devoted to musical topics up to sixty-eight, and the experiments he devised demonstrate a wide-ranging knowledge of early music theory and mathematics. The lessons covered Pythagoras’ experiments, Euclid’s division of the canon, the music of Plato’s Timaeus, and Kepler’s notions of the musical relations among the planets; he had the students create eight- and thirteen-string sonometers to explore the discovery and historical development of musical intervals, modes, scales, melodies, harmonies, and chord progressions from the most ancient tunings through the experimental temperaments of the Baroque and early Classical period to modern equal temperament. (The sonometer in the accompanying photo is located in the St. John’s College Music Library.)

Fig. 3

Carter’s Sonometer

[ 36 ] Moreover, these lessons were coordinated with the readings that students were doing in the mathematics tutorial and seminar. According to the teaching schedule, the Freshman music laboratories would have occurred during the fifteenth through the eighteenth weeks of the school year, that is, probably in December and January. These units therefore would have followed previous laboratory studies of physical phenomena dealing with rectilineal angles, areas, weights and measures, light, lenses, and circular motion, and mathematical studies of polygons, simple ratios, compound ratios, and simple quadratic equations.

[ 37 ] Virgil Blackwell, Carter’s personal assistant, calls the two years at St. John’s the “lost years,” because they have not been much discussed by Carter’s biographers. He also told me that Carter had a good laugh when he saw the image of the sonometer I had sent via email;(30)Personal communication, Nov. 6, 2011. he remembered that “the students made the sonometer.”(31)Personal communication, Nov. 8, 2011. These remarks indicate that Carter approached the teaching of the music laboratories in the participatory, exploratory, experimental spirit of the New Program. He and his students would investigate the most complex concepts of tuning by means of the sonometers they built with their own hands, by applying bridges, weights, rulers, wires, nails, rubber mallets, bows, and resin to manipulate string lengths in an effort to discover the mathematical underpinnings of the auditory phenomena.

[ 38 ] While Carter thus set the foundations for the mathematical study of music at St. John’s, his initial designs began to be modified in the very next school year. Since the program of study at the college has always been under continuous revision, the music labs too went through changes over the years, until Carter’s original contributions were all but forgotten. His four laboratory exercises lay neglected in the library archives, together with the drawings of the eight- and thirteen-stringed sonometers. The seventy-year old sonometer, discovered some years ago in a basement storage room, was tucked away as a curious relic in a corner of the music library, its purpose and origin unknown.

1941-1942: Tutor of Greek, Mathematics, and Seminar

[ 39 ] In the 1941-42 school year, Carter’s friend Nicholas Nabokov arrived at St. John’s to take over the duties of Director of Music. Nabokov expanded the music program considerably. While the Glee Club continued, he added two new vocal groups: a chamber choir and something called the “Vespers” group. He also started a chamber ensemble and a community orchestra.

[ 40 ] Since Carter had relinquished his responsibilities to Nabokov, he then took on the regular teaching schedule of a tutor at the College. Initially it was difficult to determine exactly what he taught during his second year. After seventy years, the original records of teaching schedules and tutor assignments had been lost. But the current Assistant Registrar at St. John’s, Jacqueline Thoms, recently discovered some ledgers detailing all the classes attended by each Senior in the graduating class of 1945 during their four-year career, together with the names of their tutors. By compiling the classes that these students attended during their Freshman year, it was possible to identify the classes Carter taught during the 1941-42 school year, and the number of students in each of his classes.(32)Ledger 1941-42.

[ 41 ] This research confirms the facts that were already known about Carter’s teaching that year. He taught Freshman Greek, Freshman Mathematics, and his four Freshman Laboratory units when they came up in December or January. In addition, he co-led a Freshman Seminar with fellow tutor Bernard Peebles.

Elliott Carter's Teaching Schedule, 1940-41

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | |

| 9-10 | Greek Tutorial 9 students |

Greek Tutorial 9 students |

Greek Tutorial 9 students |

Greek Tutorial 9 students |

Greek Tutorial 9 students |

| 10-11 | |||||

| 11-12 | Mathematics Tutorial 9 students |

Mathematics Tutorial 9 students |

Mathematics Tutorial 9 students |

Mathematics Tutorial 9 students |

Mathematics Tutorial 9 students |

| 12-2 | |||||

| 2-5 | Laboratory Freshman Exercises 15-18 [students] |

||||

| 5-8 | |||||

| 8-10 | Seminar with Peebles 18 students |

Seminar with Peebles 18 students |

[ 42 ] Although Carter’s responsibilities as Director of Music were no doubt heavy, his responsibilities as a tutor were even heavier. In addition to facilitating discussion in his Greek and Mathematics tutorials, he also had to set up, prepare, and lead the laboratory exercises for the students. All these classes also required him to read and respond to short papers and reports, and to devise and correct occasional quizzes. In his Seminar he had to complete the extensive required readings from the Great Books, moderate the two-hour long seminar discussions twice a week, read longer papers, and conduct oral examinations. In addition, he also would have spent considerable time advising students individually on their classwork, and helping them to write, revise, and complete the required essays.

[ 43 ] One can get an idea of the sheer amount of reading Carter had to do for seminar alone from the schedule of readings from the 1940-41 school year, which would not have changed much during the following year:

| September 26 | Homer, Iliad, 1 | November 11 | Aeschylus, Choephoroe, Eumenides |

| September 30 | Homer, Iliad, 2-4 | November 14 | Plato, Charmides, Lysis |

| October 3 | Homer, Iliad, 5-10 | November 18 | Plato, Symposium |

| October 7 | Homer, Iliad, 11-16 | November 21 | Herodotus, History, 1-2 |

| October 10 | Homer, Iliad, 17-24 | November 25 | Herodotus, History, 3-5 |

| October 14 | Plato, Ion, Laches | November 18 | Herodotus, History, 6-7 |

| October 17 | Homer, Odyssey, 1-8 | December 2 | Herodotus, History, 8-9 |

| October 21 | Homer, Odyssey, 9-16 | December 2 | Plato, Gorgias |

| October 24 | Homer, Odyssey, 17-24 | December 2 | Plato, Republic, 1-2 |

| October 28 | Plato, Meno | December 12 | Plato, Republic, 3-5 |

| October 31 | Plato, 3 works | December 16 | Plato, Republic, 6-7 |

| November 4 | Plato, Phaedo | December 19 | Plato, Republic, 8-10 |

| November 7 | Aeschylus, Agamemnon | ||

| Christmas Vacation | |||

| January 6 | Plato, Cratylus | February 13 | Plato, Philebus |

| January 9 | Plato, Phaedrus | February [17] | Plato, Timaeus |

| January 13 | Sophocles, 2 works | February 20 | Aristotle, Categories |

| January 16 | Aristotle, Poetics | February 27 | Aristotle, Prior Analytics |

| January 20 | Sophocles, 2 works | March 3 | Aristotle, Posterior Analytics |

| January 23 | Euripides, 3 works | March 6 | Aristotle, Posterior Analytics |

| January 27 | Plato, Parmenides | March 10 | Aristotle, Posterior Analytics |

| January 30 | Plato, Theatetus | March 13 | Thucydides, History, 1-2 |

| February 3 | Plato, Sophist | March 17 | Thucydides, History, 3-4 |

| February 6 | Hippocrates, 4 works | March 20 | Thucydides, History, 5-6 |

| February 10 | Hippocrates, 5 works | ||

| Spring Vacation | |||

| March 31 | Thucydides, History, 7-8 | May 1 | Lucretius, On the Nature of Things |

| April 3 | Aristophanes, 3 works | May 5 | Lucretius, On the Nature of Things |

| April 7 | Aristophanes, 3 works | May 8 | Euclid, Elements, Bks. 5, 10, 13 |

| April 10 | Aristotle, Politics, 1-4 | May 12 | Aristarchus, Sun and Moon |

| April 14 | Aristotle, Politics, 5-8 | May 15 | Aristotle, Physics, 1 |

| April 17 | Plutarch, 5 works | May 19 | Aristotle, Physics, 2-3 |

| April 21 | Plutarch, 3 works | May 23 | Aristotle, Physics, 4 |

| April 24 | Nicomachus, Arithmetic, 1 | May 26 | Archimedes, Works (unspecified) |

| April 28 | Nicomachus, Arithmetic, 2 | May 29 | Lucian, True History |

| (Barr Buchanan Series III, Curriculum in Motion, December 1940, Box 2, Folder 25, St. John’s College Library Archives) | |||

[ 44 ] As we have seen, Carter’s remarkable education prepared him well for his duties as a tutor at St. John’s. Nevertheless, the new experience of teaching Freshmen, the pace of the curriculum, and the many hours spent meeting individually with students must have kept him extraordinarily busy.

1940-1942: Elliott Carter, Composer

[ 45 ] According to Virgil Blackwell, Carter says that his choral work The Defense of Corinth was written during his time at St. John’s College, and that he began working on the sketches for his Symphony No. 1 immediately after leaving the college, when he and his wife moved west to Arizona and New Mexico. Both works relate to our consideration of Carter’s career at St. John’s.

[ 46 ] The Defense of Corinth for speaker, men’s chorus and piano four hands, was commissioned by the Harvard Glee Club and performed by them on March 12, 1942, with G. Wallace Woodworth conducting (Schiff 1983, 329). The work has many similarities to Stravinsky’s Les Noces, Schoenberg’s Moses and Aaron, and Orff’s Carmina Burana. It is based on a passage from “The Author’s Prologue” to Book Three of Gargantua and Pantagruel by François Rabelais (1495-1553). The text could be construed as a satirical commentary on militarism and a mockery of war-hysteria. Carter’s work was composed close to the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The satirical attitude toward war displayed in the piece did not, however, carry over into Carter’s personal life: he attempted to enlist in military service as soon as the United States entered hostilities, as did many of his St. John’s students over the next few years. Because he had terrible allergies, however, he was rejected for active duty on health grounds. Eventually, from late 1943 until June 6, 1944 he worked as a musical advisor for the U.S. Office of War Information.(33)Wierzbicki 2011, 29.

[ 47 ] Whatever his personal political feelings, Carter’s The Defense of Corinth is a musical metaphor for his situation as composer in a world made mad by war. The work is divided into three distinct sections. In the first section, a speaker and male chorus use the spoken narration, speech-song, and full singing of a speaker and male chorus joined with a four-hand piano accompaniment to build up musical textures in imitation of the building up of the Corinthian war effort against Philip of Macedon:

Everyone did watch and ward, and not one was exempted from carrying the basket. Some polished corslets, varnished backs and breasts, cleaned the head-pieces, mail-coats, brigandines, salads, helmets, morions, jacks, gushets, gorgets, hoguines, brassars and cuissars, corslets, haubergeons, shields, bucklers, targets, greaves, gauntlets, and spurs. Others made ready bows, slings, crossbows, pellets, catapults, migrains or fireballs, birebrands, balists, scorpions, and other such warlike engine expugnatory and destructive Hellepolides. They sharpened and prepared spears, staves, pikes, brown bills, hailberds, long hooks, lances, zagayes, quarterstaves, eesleares, partisans, troutstaves, clubs, battle-axes, maces, darts, dartlets, glaives, javelins, javelots, and truncheons. They set edges upon scimitars, cutlasses, badelairs, backwords, tucks, rapiers, bayonets, arrow-heads, dags, daggers, mandousians, poniards, whinyards, knives, skeans, shables, chipping knives, and raillons. . . . Every man exercised his weapon.(34)Rabelais 2004, 265.

[ 48 ] Accompanying this relentless concatenation of weaponry, the musical elements continue to pile up, steadily getting louder, sharper, more percussive; the voices progress to confused speaking and shouting, reaching a climax in pure noise.

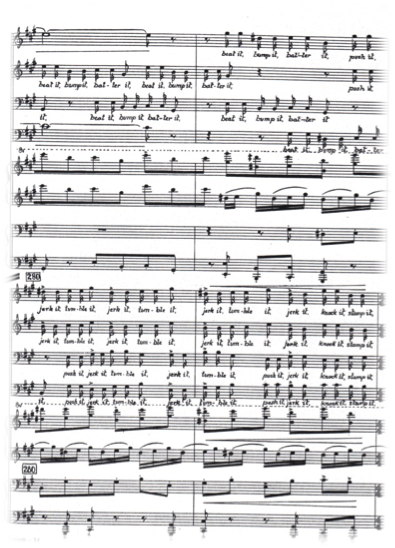

Fig. 4

The Defense of Corinth holograph score (Library of Congress, ML96.C288 [Case])

[ 49 ] The brief second section is a quieter setting in which the main character, Diogenes, seeing everyone around him so hard at work making war while he is not employed by the city in any way, contemplates what he should do. Surely this must reflect Carter’s state of mind at the time: unable to join the war effort because of his allergies, he finds himself surrounded by young men, including his students, preparing for and leaving for war. Like Diogenes, he must have been contemplating his situation, and what he should do next.

[ 50 ] In the third section Diogenes, in a moment of sudden awakening, is roused and inspired by the war effort going on all around him. He leaves town, goes toward a little hill near Corinth called Cranie,

and there on the strand, a pretty level place, did he roll his jolly tub, which served him for a house to shelter him from the injuries of the weather: there, I say, in a great vehemecy of spirit, did he turn it, veer it, wheel it, whirl it, frisk it, jumble it, shuffle it, huddle it, tumble it, hurry it, jolt it, justle it, overthrow it, evert it, invert it, subvert it, overturn it, beat it, thwack it, bump it, batter it, knock it, thrust it, push it, jerk it, shock it, shake it, toss it, throw it, overthrow it, upside down, topsy-turvy, arsiturvy, tread it, trample it, stamp it, tap it, ting it, ring it, tingle it, towl it, sound it, resound it, stop it, shut it, unbung it, close it, unstopple it. . . . And then again in a mighty bustle, he . . . slid it down the hill, and precipitated it from the very height of Cranie; then from the foot to the top (like another Sisyphus with his stone) bore it up again, and every way so banged it and belabored it that it was ten thousand to one he had not struck the bottom of it out.(35)Rabelais 2004, 265.

[ 51 ] This text is set with hocket imitation and short fugue-like segments, piling the words on top of one another, so that the result is quite similar to the raucous first section. And also like the first section, it undergoes a steady crescendo until it reaches a thundering climax.

[ 52 ] At this point, the final section begins. The narrator speaks the last few lines quietly:

When one of his friends had seen, and asked him why he did so toil his body, perplex his spirit, and torment his tub, the philosopher’s answer was that, not being employed in any other charge by the Republic, he thought it expedient to thunder and storm it so tempestuously upon his tub, that amongst a people so fervently busy and earnest at work he alone might not seem a loitering slug and lazy fellow.(36)Rabelais 2004, 265.

[ 53 ] It is not too far-fetched to imagine that Carter may have seen himself in the role of Diogenes, and that composing this wild, raucous piece was Carter’s way of “tormenting his tub” in order to avoid being seen as doing nothing while everyone around him was consumed by the war effort. There is certainly no doubt that the atmosphere on campus after the declaration of war resembled the situation in Rabelais’ Corinth. The preparations for the war were both pervasive and intrusive. There were military exercises on campus, information poured in about military employment opportunities, new classes appeared on the mechanics of gasoline engines and the electronics of radio devices (The Collegian, various issues from 1942). Periodic lectures about the causes and progress and status of the war were offered, and a rash of military enlistment by the students so depleted enrollment that by the war’s end there was great concern that St. John’s might have to close its doors. The Defense of Corinth certainly reflected the conditions that surrounded Carter while he composed the work, and no doubt reflected his inner state as well.

[ 54 ] Carter’s second major work of 1942 is his Symphony No. 1, which he completed in Santa Fe, New Mexico, about six months after leaving St. John’s. In the sketches for this work, which are housed at the Library of Congress along with the holograph score and the revised score from 1954 (Carter 1942), it seems that Carter is again playing the role of Diogenes tormenting his tub; this time, however, the tub is the Symphony. The 184 pages of sketches show beating, battering, slicing, compressing, enlarging, twisting, and transforming of apparently innumerable musical ideas from all three movements in the finished piece. There is an explosive vitality combined with a restless energy in the musical handwriting, which seems almost thrown onto the pages in instants of creative inspiration.

Fig. 5

Sketches for Symphony No. 1 (Library of Congress ML96.C288 [Case])

[ 55 ] What is more, this material is not limited to musical notations. The sketches fall into ten categories: 1. Fragments of one to many lines, some crossed out; 2. single-line drafts worked out and developed; 3. two-part piano reductions of sections in progress, for playing at the piano; 4. fair copies of two-part piano reductions, including one of the entire first movement, 5. reductions of three to five parts, for working out complex ideas; 6. larger orchestral reductions with instrumentation noted; 7. full-score drafts with instrumentation noted; 8. verbal notes, such as “add a few dotted rhythms” or “avoid too many accents on the first beat”; 9. letter designations for the various motives and themes, such as “A,” “B,” “C,” and so forth; 10. verbal notes on the sequential organization of musical elements within a section.

[ 56 ] Out of all these disparate elements, Carter fashioned an elegant, hand-copied full score of 149 pages on December 19, 1942. In this pre-Xerox, pre-computer era, it must have taken a considerable amount of time just to write out such a meticulous manuscript. And if one adds to that the amount of time that was clearly devoted to beating the tub while inventing, revising, discarding, reworking, drafting, and re-drafting the thousands of sketches, it seems plausible to think that Carter began working on the symphony while still at St. John’s. Blackwell, however, indicated that Carter was “adamant” about the fact that he began working on the piece only after leaving St. John’s. If that is correct, then the explosive creative energy displayed in the sketches suggests that his compositional urge had been suppressed by his intellectual and instructional responsibilities at St. John’s, so that once those responsibilities were lifted, his musical imagination was able to generate ideas profusely.

[ 57 ] The Symphony No. 1 is a Janus-faced work, looking backward toward the influence of slightly older contemporaries like Roger Sessions, Roy Harris, and Aaron Copland, but also forward toward traits that would become characteristic of Carter’s style—cross-accents and irregular groupings of rhythms, interplay of tonal centers, fluidity in the shaping of musical motives, a transformational approach to motivic development, evocative orchestral coloring (particularly in the use of woodwinds), and simultaneous balancing of dissimilar ideas (Schiff 1983, 117-121). The Symphony already shows the continuous ebb and flow from sparseness to complexity, from delicacy to brutality, from quietness to cacophony, from simple textures to convoluted contrapuntal intricacy that would appear fully developed in his masterpiece, the Concerto for Orchestra of 1969. One can see in the sketches and hear in the music that 1942 was a time of compositional turbulence for Carter. He must have been bursting with competing ideas from old and new sources, all pushing him toward discovering his unique artistic voice. Whatever attractions the undeniably novel environment of St. John’s held for him as a curious, intelligent, inquisitive, and liberally educated thinker, he must have felt that, in his heart, he was essentially meant to be a composer. What else could he do but leave, so that the potential composer within him could become actual?

Epilogue: Elliott Carter, Composer and Liberal Artist

[ 58 ] In the years just after leaving to pursue his composing career, Carter wrote two essays that relate to his tenure as a tutor at St. John’s. The first, “Music as a Liberal Art” (Carter 1944), which was written only two years after he left the college, discusses the decline of music as a liberal art in America. Citing the fundamental importance of musical training in Plato’s Timaeus and Aristotle’s Politics and Poetics, Carter laments the fact that music has become a specialized and technical discipline, divorced from the connection it once had to the other liberal arts. At St. John’s, however, he says, “music has actually been taken out of the music building. It is no longer the special study of the specialist, of the budding professional. Instead it is examined in the classroom, seminars, and laboratories, in an effort to give it a working relationship with all other knowledge” (Carter 1944, 105). After describing in greater detail the relations between music, mathematics, philosophy, and physics in the St. John’s curriculum, Carter maintains that

[w]hen the student sees the interconnection of all these things, his understanding grows in richness. And since today no widely accepted esthetic doctrine unifies out though on the various aspects of music, such a plan at least conjures up the past to assist us; it helps to raise the various philosophical questions involved. In one way or another these questions must be considered, for it is not enough to devote all our efforts to acquiring the technical skill essential to instrumentalists, composers, and even listeners. There must be good thinking and good talking about music to preserve its noble rank as a fine art for all of us, and the college is one of the logical places for this more considered attitude to be cultivated.(37)Carter 1944, 106.

As we have seen, Carter’s view of music education was deeply attuned to the experimental approach being taken at St. John’s. This alignment must have made his teaching in the New Program a meaningful and rewarding experience for him, and this article is evidence of how highly he regarded the method of musical studies at St. John’s.

[ 59 ] The second article, “The Function of the Composer in Teaching the General College Student” (Carter 1952), reveals a second aspect of Carter’s understanding of music as a liberal art. While it is certainly true that reconnecting music to the other liberal arts provides students with a more profound understanding of music than specialized musical instruction, it is also true that connecting the other liberal arts to music provides students with a more profound understanding of their own inner life than specialized instruction in any discipline. In this article, Carter discusses the difference between the “outer-directed” man, whose primary focus is on adapting his inner life to the demands of society, and the “inner-directed” man, whose primary focus in on adapting the demands of society to his individual conscience and imagination. Both the teaching scholar and the teaching artist, according to Carter, are trying to “preserve that liveliness of the individual mind so important to our civilization.”(38)Carter 1952, 151. But they go about it in different ways.

[ 60 ] On the one hand, the teaching scholar of the general music student aims for the “all-embracing, the dispassionate view of his subject” and “tries to find a harmonious and rationally explicable pattern in the past and present.” By contrast, the teaching artist is “only occupied with those aspects of music most important to him as an individual”; his goal as an artist is to create unique artworks that can move his audience and possibly shift societal demands. In short, the teacher treats music objectively, the artist, subjectively. This basic difference in attitude toward the subject gives rise to a difference in emphasis that marks the gulf between teaching scholar and teaching artist: the scholar highlights the “pastness of the past,” and communicates to students the impassive historicity of the subject matter, whereas the artist highlights the “presentness of the past,” and communicates to students the pliability of the past as material for the reshaping powers of the creative individual. Carter admonishes higher education for its preference for teaching scholars, who give students “scraps of information” about the past; he praises the teaching artist for “constantly trying to find a more powerful method of making his students more culturally alive,” by reshaping the past into a living and vital present.(39)Carter, 1952, 153-154. At present, Carter emphasizes,

we have got to help our students to realize that to enjoy the arts creatively and imaginatively will be far more rewarding to them as individuals in terms of stimulating vividness of thought and feeling, quickness of understanding, and ingeniousness in dealing with new problems—far more rewarding than the mere passive enjoyment which most mass-produced entertainment invites.(40)Carter 1952, 155.

[ 61 ] The contemporary serious composer must be able to engage students in the “presentness of the past,” must be able to absorb the musical past, sublimate its essence, and recast it into new shapes that speak movingly to the present while at the same time embodying what was most enduring in the music of the past.

[ 62 ] At this point in the article, Carter once again describes the music program at St. John’s. Because the college wanted to move away from the teaching scholar’s approach to music toward a teaching artist’s point of view, “they called in a composer on the hunch that he would grasp the idea more than other members of the musical profession, and a plan was worked out from which it was hoped that students of widely different musicality could make contact with art.”(41)Carter 1952, 156. It was hoped that students might attain “esthetic awareness” by studying music under the guidance of a composer, who could help the students see beyond the “pastness of the past” to the “presentness of the past” by showing them music history and the masterworks of the great composers through the contemporary lens of his actively creative perspective.

[ 63 ] But the teaching artist is not limited to exhibiting his works to his students. On the one hand, by means of his compositions, the teaching artist “can give life to and express all those things which, at best, he can but poorly indicate with words.” On the other hand, “sometimes verbal teaching, that is, the articulation of the principles and ideas he strives to embody in his works, is a valuable part of his development as a composer; and in this case he can be a useful member of the academic world.”(42)Carter 1952, 158. In this last circumstance, the artist can bring his students along into the internal aspect of his creative process, and possibly stimulate them to develop their own creative powers.

[ 64 ] In this essay, as in much of his music, Carter seems to be trying to hold together two complex and somewhat contradictory themes. It is simultaneously true not only that the composer is the best teacher when he is writing music and indirectly teaching others, but also that his students, and the composer himself as well, also benefit from his talking about music and directly teaching others. The two truths conflict. The working composer must be somewhat solitary; he must spend time away from others pursuing his personal creative projects. The teaching composer must engage in communal life; he must bring “presentness to the past” by speaking with others about listening to, performing, and creating music. For the teaching artist, this counterpoint of competing activities can enrich and deepen his creative life. But no one can do both at the same time.

[ 65 ] For Carter, his two years at St. John’s as a teaching artist seem to have stimulated his already intense creative drive – so much so, that he found it necessary to stop teaching in order to focus on his art. Over the years, he has returned to the role of teaching artist often, giving innumerable workshops, coaching prospective composers in academic and non-academic settings, lecturing and writing essays about music education for academic audiences. One could argue that it was Carter’s decision to join the faculty at St. John’s that provided the opportunity for him to become an extraordinary teaching artist, and that it was his decision to leave St. John’s that provided the opportunity for him to create the many enduring artworks through which he could reach an ever widening circle of students with his teaching. Without both coming and going from St. John’s, Elliott Carter could not have become Elliott Carter.

Footnotes

8. Edwards 1971, 50, 55. Emphasis added.

9. Edwards 1971, 51, 56. Emphasis added.

15. Nabokov 1940.

16. See Murphy 1996 and Rule 2009 for the facts in this section.

17. Barr 1941, 44.

19. Carter, 1962.

20. St. John’s College Catalogue 1940-41.

21. The Collegian, Oct. 19, 1940.

22. St. John’s College Yearbook, 1941, 30.

23. The Collegian, Nov. 13 and Dec. 13, 1940.

24. The Collegian, Nov. 1, 1940.

25. The Collegian, Jan. 31, 1941.

26. The Collegian, Feb. 14, 1941.

28. Carter 1941, 1.

30. Personal communication, Nov. 6, 2011.

31. Personal communication, Nov. 8, 2011.

32. Ledger 1941-42.

Bibliography

Blackwell, Virgil. 2011. Personal email messages to and telephone conversations with the author in November.

Buchanan, Scott. 1940. “Music,” three-part handwritten note dated November 8, at Harvard University Libraries, MS Am 1992, No. 1547.

Carter, Elliott. 1941. “Manual of Music Notation.” St. John’s College Library Archives.

———. 1942. Sketches for Symphony No. 1, Library of Congress Performing Arts Manuscripts, ML96.C288.

———. 1950. The Defense of Corinth. Library of Congress Performing Arts Manuscripts, ML96.C288.

———. 1944. “Music as a Liberal Art,” Modern Music 22:1, 12-16. Reprinted in Else Stone and Kurt Stone, The Writings of Elliott Carter (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1977), 105-109.

———. 1952. “The Function of the Composer in Teaching the General College Student,” Bulletin of the Society for Music in the Liberal Arts College 3:1, Supplement 3. Reprinted in Else Stone and Kurt Stone, The Writings of Elliott Carter (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1977), 150-58.

———. 1962. Personal letter to Scott Buchanan. St. John’s College Library Archive, Barr Personal Papers, Series 2, Box 10, folder 20.

The Collegian. (St. John’s College newspaper.) Various issues, 1940-1941, 1941-1942.

Maryland State Archives, St. John’s College Special Collection, MSA 5698.

Edwards, Allen. 1971. Flawed Words and Stubborn Sounds: A Conversation with Elliott Carter. New York: W. W. Norton and Company.

Ledger 1941-42. Large format class ledger. St. John’s College Registrar’s Office Archives.

Murphy, Emily A. 1996. “A Complete and Generous Education”: 300 Years of Liberal Arts, St. John’s College, Annapolis. Annapolis, Maryland: St. John’s College Press.

Nabokov, Nicholas. 1940. Letter to Stringfellow Barr, June 22, 1940. St. John’s College Registrar’s Office Archive.

Nelson, Charles. 1997. Stringfellow Barr: A Centennial Appreciation of His Life and Work, 1897-1982. Annapolis, Maryland: St. John’s College Press.

Rabelais, Francois. 2004. Five Books Of The Lives, Heroic Deeds And Sayings Of Gargantua And His Son Pantagruel, translated by Sir Thomas Urquhart and Peter Motteux. Whitefish, Montana: Kessinger Publishing.

Rule, William Scott. 2009. Seventy Years of Changing Great Books at St. John’s College. Educational Policy Studies Dissertations. Paper 37. http://digitalarchive.gsu.edu/eps_diss/37

Schiff, David. 1983. The Music of Elliott Carter. New York: DaCapo Press.

St. John’s College Catalogue 1940-41. St. John’s College Registrar’s Office Archives.

St. John’s College Yearbook, 1940-1941, 1941-1942. St. John’s College Library Archives.

Stone, Else and Kurt. 1977. The Writings of Elliott Carter: An American Composer Looks at Modern Music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Wierzbicki, James Eugene. 2011. Elliott Carter. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Other Resources Located at St. John's College

In the St. John’s College Library Archives

Photo of Elliott Carter at desk Musical programs from 1940-41 Carter’s Five Laboratory Manuals:

“Musical Intervals and Scales” (Laboratory Exercise 15, 1940)

“The Greek Diatonic Scale” (Laboratory Exercise 16, 1940)

“The Just Scale and Its Uses” (Laboratory Exercise 17, 1940)

“The Keys in Music” (Laboratory Exercise 18, 1940)

“Manual of Musical Notation” (1 March, 1941)

In the St. John’s College Music Library

Carter’s sonometer

Carter’s four-part setting of “St. John’s Forever”