Papers from the Special Session “Elliott Carter: 10 Years On,"

at the AMS/SEM/SMT Joint Annual Meeting, New Orleans, November 10, 2022

Carter, Pedagogy, and the Undergraduate Theory Curriculum

Peter Smucker

Abstract

Curricula that characterize Carter’s music as representative of one primary theoretical concept likely perpetuate a narrow understanding and appreciation of his music. A focus on a more experiential and phenomenological approach to his music offers an opportunity to situate Carter in an undergraduate curriculum as more than simply the composer most associated with tempo modulation.

This paper therefore provides pedagogical applications of Carter’s music with a focus on the aural experience of his music, rather than technical attributes. In the first of three parts of the presentation, I orient Carter’s music in current undergraduate theory curricula. Using sample assignments, I show how a student’s assessment of Carter’s music—possibly for the first time—typically addresses technical, rather than aural features. Such approaches may offer only tangential relevance to how Carter’s music might “capture the attention” of undergraduate students, and how they can engage with it. The second part of the paper focuses on alternative pedagogical approaches to his music. Using experiences from my own classroom instruction, I show how descriptive, gestural, and other aural identifiers offer a pathway toward a more immediate connection between students and Carter’s late music. Additionally, I show the practicality of these methods, which resonate with recent increases in visual representations of music in the public sphere (Chan-Hartley 2021). In the third part of the paper, I offer three brief examples of undergraduate assignments, rubrics, and learning outcomes that use Carter’s music to illustrate these aurally focused approaches. One assignment is on aural training, another on writing and public engagement, and the third on composition.

These alternative pedagogical approaches offer ways to engage critically with Carter’s music far beyond tempo modulations. The paper provides a way for Carter’s music to no longer be confined to undergraduate course units on 20th-century techniques, and rather within a larger context of experiencing music and finding its value. Such approaches provide both accessibility and relevance for the future educators, performers, and composers that populate most undergraduate music theory courses.

Introduction: A Student’s First Encounter with Carter’s Music

[ 1 ] I owe a lot to Dr. Michael Cherlin for my interest in and love of Elliott Carter’s music. In March 2006, when I was a graduate student in music theory at the University of Minnesota, there was a massive five-day Elliott Carter festival. During that week, there were numerous concerts, scholarly papers and discussions, and an hour set aside for Carter to sit and talk to a room full of undergraduate and graduate students. Although I had heard of Elliott Carter before — likely during my undergraduate studies — this was the first time I had really experienced his music in a concentrated and meaningful way. It was during that semester that I learned how to analyze and appreciate Carter’s music from a variety of angles, particularly through Michael Cherlin’s fondness for teaching his students the theories of David Lewin, and Michael’s inescapable love of poetry. It was because of that semester of graduate school that I went on to do a project on Carter’s “Am Klavier” from Of Challenge and Love (1994) for my master’s degree and eventually my dissertation on Carter’s late chamber music at the University of Chicago.

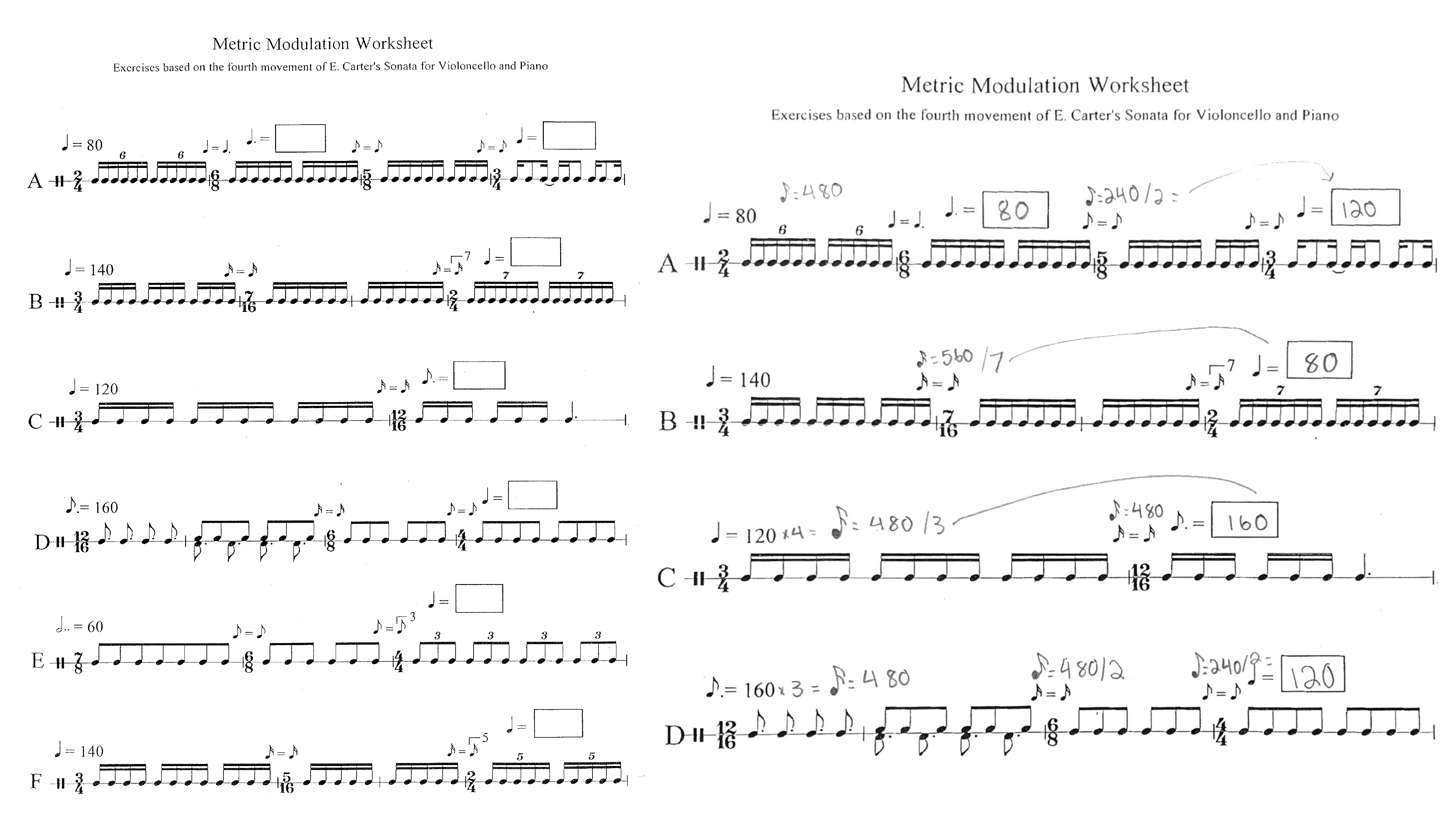

Example 1

Metric Modulation Worksheet

[ 2 ] Years after my graduate studies, when I now find myself in front of an undergraduate classroom, I still find that I am excited to talk about Carter’s music. Yet, at first I was only giving my students a worksheet that looks something like Example 1. Each line of out-of-context tempo modulations is based on excerpts from Carter’s Duo for Violin and Piano (1974). The worksheet in Example 1 holds potential for undergraduate students. It affords them the opportunity to cultivate and refine their analytical skills while broadening their understanding of compositional techniques. This pedagogical approach is inspired by foundational texts such as Stefan Kostka and Matthew Santa’s Materials and Techniques of Post-Tonal Music, 5th ed. (2018), and emphasizes the technical aspects of composition rather than focusing on individual composers. Kostka and Santa give a “relatively simple” example of a tempo modulation from Carter’s Cello Sonata (1948):

The most reliable way to calculate the new tempo is to first compute the tempo of the common note value in the first tempo:

If= 84, then

= 4 x 84 = 336

and then to figure out what that means in terms of the beat in the second tempo:

If= 336, and the new beat is the dotted quarter, then the new tempo is 336/3 = 112. (2018, 117)

[ 3 ] To the credit of my students, they dutifully calculated the shift from one tempo to another by determining the speeds of the various note values and often showed their work of multiplication and division. But for many of them – all 18-19 year old music majors – my exercise could have been their first encounter with Carter’s music; and this realization left me wanting to offer them more – a way to better express my interest in this music to them. This essay examines how we, as pedagogues, might expand our students’ exposure to Elliott Carter’s music in an undergraduate music theory curriculum, offering pedagogical strategies and curriculum designs to enhance a student’s interaction with Carter’s music.

[ 4 ] In music history courses and textbooks Carter is typically placed in the context of American modernism, and often within broad analytical contexts. This method of reception may be doing a better job introducing Carter’s music to our undergraduates than the ones used in their music theory and aural skills courses. After surveying many commonly-used undergraduate textbooks that include post-tonal, modern, and contemporary theories, it appears that a “standard” theory curriculum usually reserves Carter’s music to illustrate the topic of tempo modulation (see Clendinning and Marvin 2021; Kostka, Payne, and Almén 2018; Laitz 2016; Gotham, et al. 2021; Roig-Francolí 2021; Kostka and Santa 2018). Other texts use an occasional Carter example to highlight concepts such as intervals and voice-leading or mention him in passing (see Burstein and Straus 2020; Straus 2016; Holm-Hudson 2017) or not at all. In my survey of aural training textbooks for undergraduates, I was hard pressed to find many examples of Carter’s music beyond an occasional sight-singing example for either meter or rhythm (see Ottman and Rogers 2019; Karpinski and Kram 2017; Benward and Kolosick 2010; Phillips, Murphy, et al. 2021; Berkowitz, Fontrier, and Kraft 2017).

[ 5 ] Many of us use these textbooks successfully in our classrooms, but it is likely that curricula that characterize Carter’s music as representative of only one primary theoretical concept perpetuate a narrow understanding and appreciation of his music.(1)Anecdotally at least this appears to be so: I welcome casual conversations with my former students about their undergraduate experiences in their core music theory courses, and when I ask them about Elliott Carter, I feel fortunate when I get responses like: “He was the tempo modulation guy, right?” Assignments like the worksheet shown in Example 1 tend to address compositionally technical, rather than experientially aural, features. Such approaches may offer only tangential relevance to how Carter’s music might aurally capture the attention of our undergraduate students, and how they can engage with it if offered other tools.

Aural Pedagogy with Carter’s Music

[ 6 ] If we look for alternative ways to teach Carter’s music to undergraduates, we might do well to borrow Carter’s own words as a guide. In his 1990 interview with Jonathan Bernard, Carter offers a way forward for an aurally-focused approach. As part of a discussion on sketch studies and analytical approaches to his music, Carter says that,

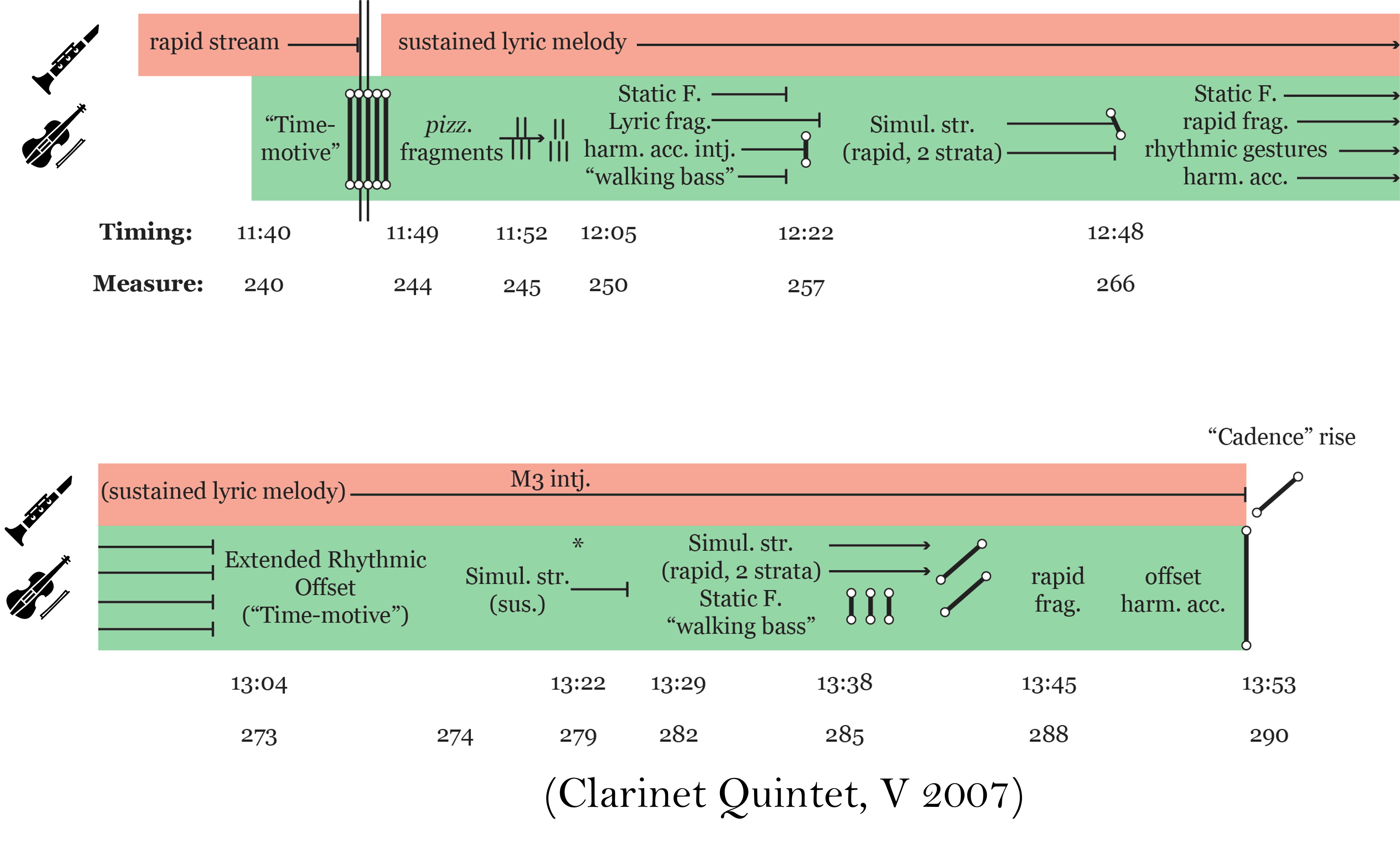

I do feel that analysis which starts by assuming the artistic value of a work, and then analyzes it, seldom tells you what it is that makes the work so interesting to hear. All it does is tell you that the chords are this way and that, and that they’re inversions of different sorts and so forth, and I keep feeling that I would rather read theoretical articles that explain why it is that the work, when heard, captures our attention, and what is so valuable about it musically, and then show what it is that contributes to this experience. (Bernard 1990, 205).

Better to take a page from our experience as aural training instructors and focus on what is exciting about this music from a listener’s perspective. If we were to adapt Carter’s words for our teaching purposes, we might say that we aim to use pedagogical methods that explain why it is that the work, when heard, captures the attention of our students.

[ 7 ] A more experiential and phenomenological approach to Carter’s music offers a way to develop such pedagogical methods in an undergraduate curriculum. Recent experiential approaches in the field of public music theory reinforce similar notions of accessibility and reception for a wider audience. Hannah Chan-Hartley (2021) demonstrates the use of a “visual listening guide,” which provides models for creating an aurally-focused approach to music. Creating an aural “map” for a piece helps indicate significant “landmarks and other features.” Although the context for public music theory is quite different from an undergraduate classroom, the methods Chan-Hartley proposes to guide a listener’s first experience of a new piece of music can be fruitfully adopted for undergraduates. Similarly, my own research into defining and cataloguing salient aural features and motives in Carter’s late chamber music has found an exciting application in the classroom. I first used this research in my undergraduate classroom in 2017 with the aim of creating an immediate interaction between Carter’s music and my students by focusing on how descriptive, gestural, and other aural identifiers offered them a pathway for hearing and responding to what they heard in this music.

Example 2

Elliott Carter, Clarinet Quintet (2007). Visual Representation (video)

[ 8 ] The dynamic, animated slides in the 30-second video in Example 2 accompany a brief excerpt from Carter’s Clarinet Quintet (2007) with descriptive, gestural, and visual representations of his music. These representations consist mostly of words that move dynamically over time, emphasizing their descriptions. My students observed five primary categories of words: melodic descriptors; textural descriptors; specific interjections that interrupt defined textures; salient gestural and aural cues; and formal “aural” boundaries defined by combinations of defined aural cues, textures, and silence. Even without the definitions of these terms (which we discussed after listening to the excerpt), my hope was that my students would quickly synthesize associative meanings with what they were hearing in real time.

[ 9 ] When I first decided to do this exercise, I wasn’t sure what to expect. To my delight, after we listened to and watched this excerpt of Carter’s music, I said something as simple as, “tell me what you think.” The impact was immediate. It was the response that most of us yearn for when teaching undergraduates. Multiple hands went up, some students were initially talking over each other, and the conversation evolved such that, at least in my memory, it reached the point where I had to say something like, “this is a great conversation, but we’re running out of time and need to move on!” The success of this assignment was in marked contrast to more calculation-based exercises like the one in Example 1 and prompted me to follow up with others.

Sample Assignments for the Undergraduate

[ 10 ] The three different assignments offered here incorporate Carter’s music but with optional—rather than required – technical analysis. For each sample assignment there is an overview, potential learning outcomes, possibilities for assessment, and a “next-level” example that includes more advanced music-theoretical topics for ways to expand student engagement with the music. All the following assignments and courses may be adapted to best fit the needs of the instructor.

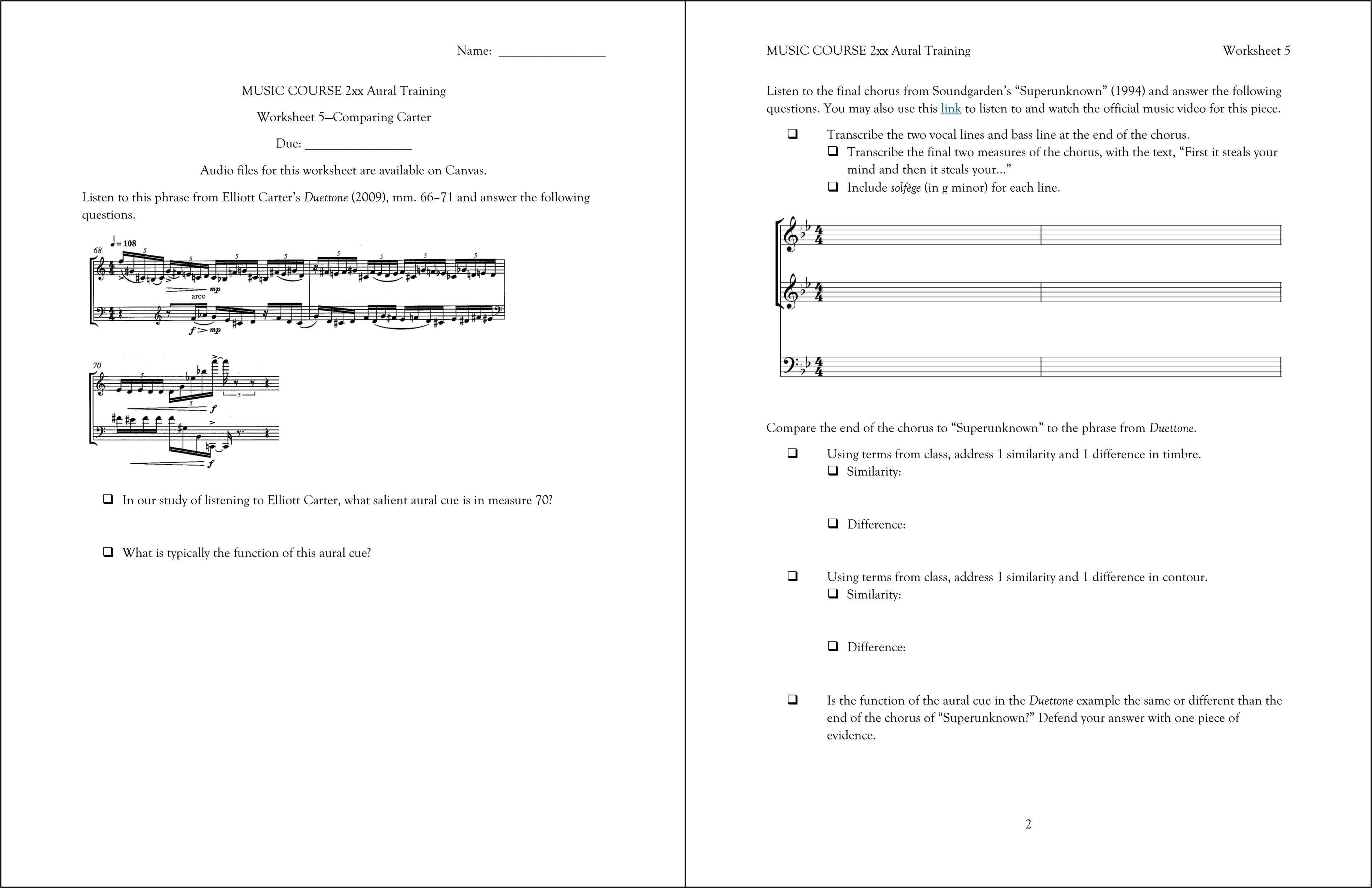

1. Aural Training: Comparison

[ 11 ] In the assignment shown in Example 3, students listen to and compare excerpts of Elliott Carter’s music and a pop song. The first excerpt in this worksheet, from Carter’s Duettone (2009), prompts the students to identify salient aural features, such as the final “wedge-like” gesture in measure 70, which could have a specific function depending on its music context. Instructors may use preexisting aural functions (e.g., cadential, timbral, registral, formal, etc.), or involve the students in defining these functions through their own experiences of the music. The second part of this assignment provides a transcription task for the end of the chorus of Soundgarden’s 1994 song, “Superunknown.” In a transcription assignment like this one, students can listen to a brief excerpt from a pop song as many times as they want and use their dictation skills to complete the tasks.

Example 3

Assignment #1. “Comparing Carter.”

[ 12 ] Why do this assignment? What is the benefit in comparing a violin duet of Elliott Carter and a grunge-rock song by Soundgarden? Comparing similar aural contour gestures and the function of these gestures can help students synthesize ideas across different styles of music. For this reason, the latter part of the assignment asks students to engage critically with contour, timbre, and aural function in both excerpts. If your college or university works through cycles of assessment and accreditation, stated learning objectives may be a necessary and useful part of the process of designing assignments. When we develop alternative theory pedagogies, considering these learning objectives may help focus our work.

[ 13 ] For this assignment, we could adapt and report the following learning objectives:

- Define and identify specific functions of aural features across different musical styles

- Transcribe melodic excerpts, including solfège and rhythmic syncopation

- Build vocabulary to compare musical timbre

- Build vocabulary to compare musical contour

Example 3A

Assignment #1 Grading Key

[ 14 ] A suggested grading key linking assessment to these learning outcomes is shown in Example 3A. A simple point spread for the functions and aural cues defined in the classroom can suffice. The transcription portion of the assignment focuses on the student’s rhythmic and melodic dictation skills. Grading should be mostly objective here, although the grader may need to consider situations such as incorrect solfège that nonetheless matches the incorrect pitches. The comparison questions are more subjective, as they force the students to think about how the contour of the lines in the Carter duet may or may not function in the same capacity as the diverging vocal and bass guitar lines in the Soundgarden song.

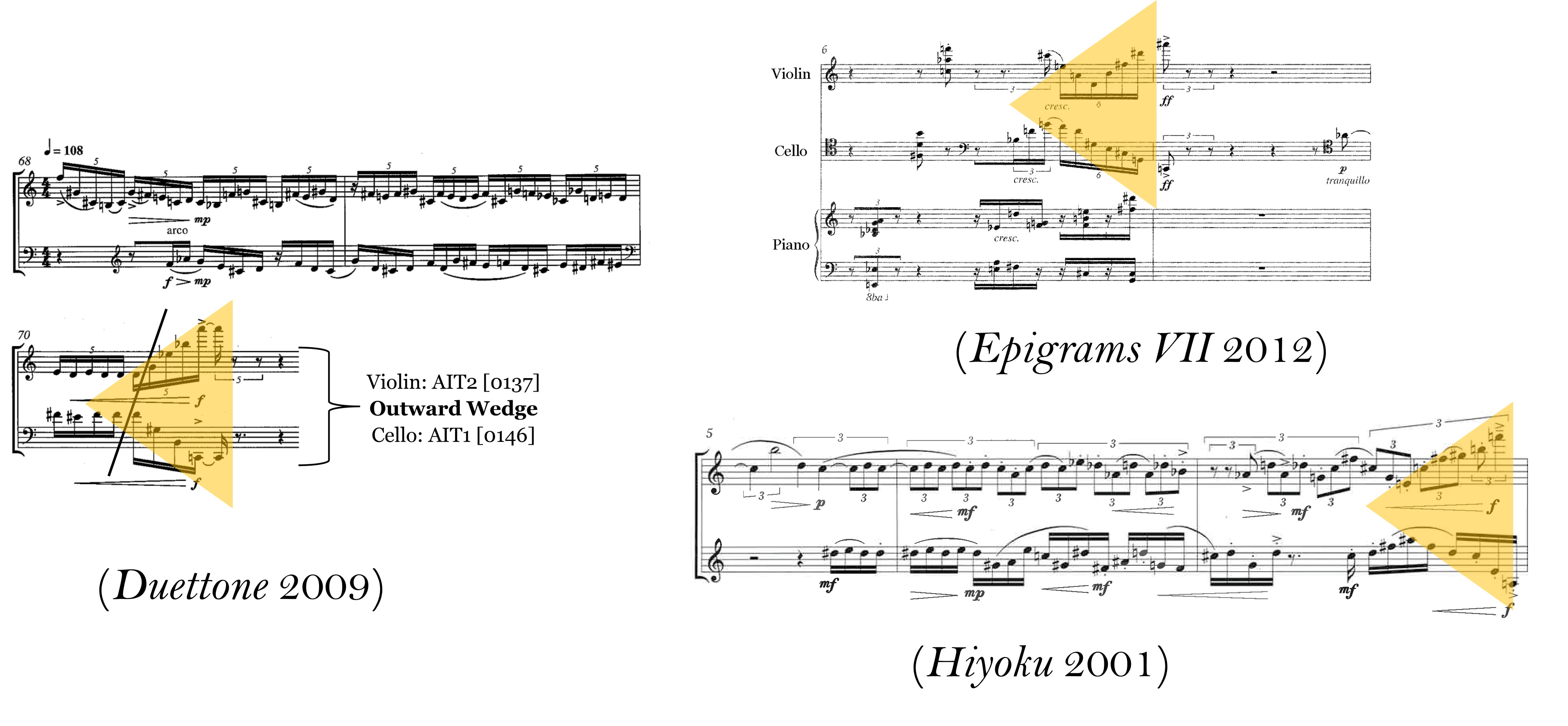

Example 4

Assignment #1 Expansion: Gestural Cues in Carter’s Music

[ 15 ] Depending on the level of the student, there may be ways to include more technical analysis. For example, Example 4 includes several excerpts from Carter’s music that involve the “outward wedge” gesture. As a part of a class discussion and in further study, students might look more closely at the pitch content of these gestures, such as the combination of the two all-interval tetrachords in the Duettone excerpt. Depending on the scope of the class, this portion of study may only involve recognition of this salient gesture in Carter’s music, or potentially a more detailed discussion of the function of tetrachord or hexachord completion for non-tonal cadential purposes.

2. Aural Training: Model Composition

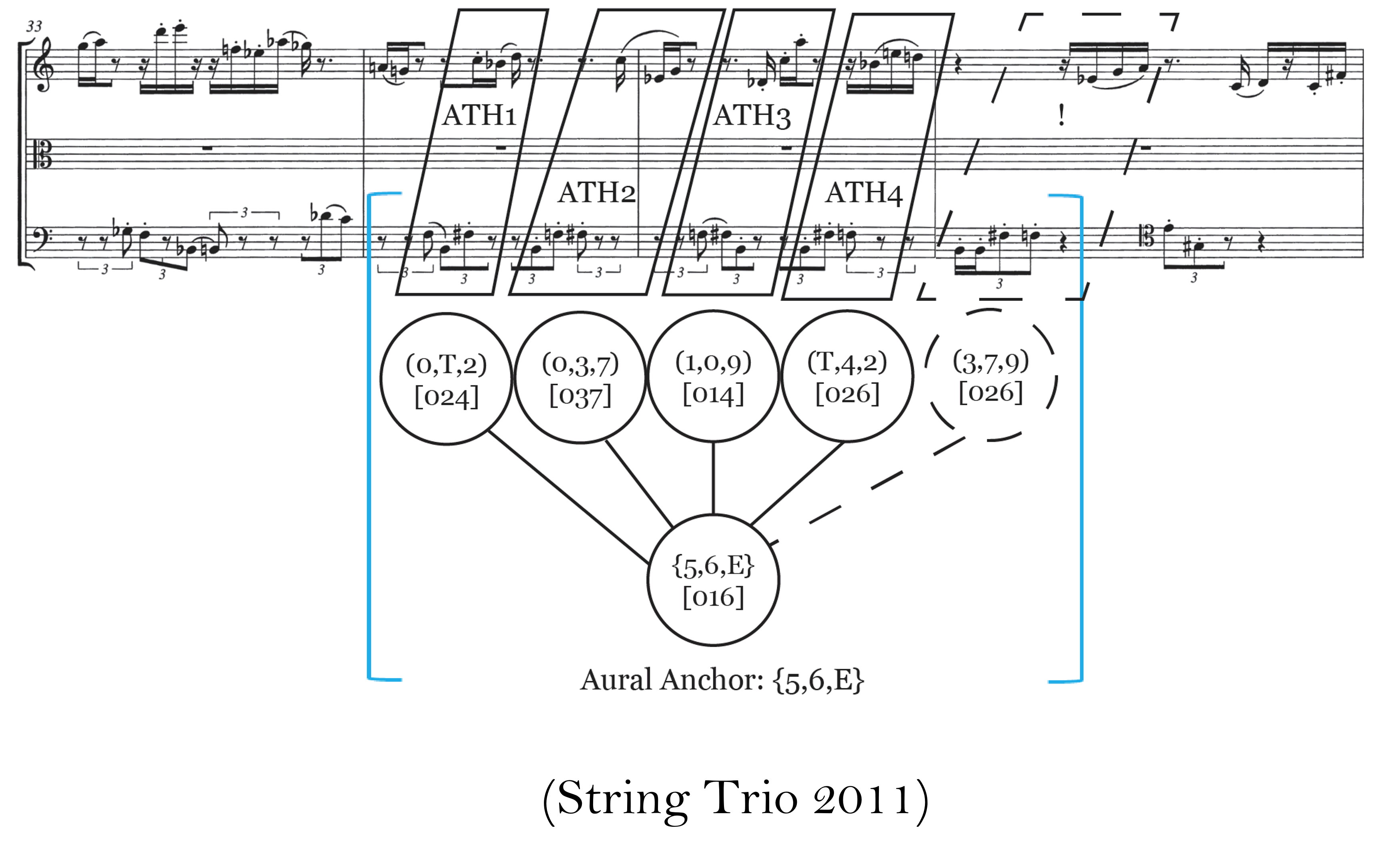

[ 16 ] In the second assignment, students are taking a hypothetical composition class—or a composition component of a music theory class—that asks them to model various composers, textures, and techniques. Students listen to and consider an excerpt from Carter’s String Trio (2011), shown in Example 5, which contains a prominent motive that anchors the passage with an interlocking melodic texture shared between two string instruments. Then, with a focus on combining a salient aural motive with other, less repetitive motives, students must compose two different passages in two different textures (which are presumably defined earlier in the course).

Example 5

Assignment #2. Model Composition

[ 17 ] Potential learning outcomes for this assignment might include the following:

- Compose short excerpts of music modeled on a variety of composers from the 20th and 21st centuries.

- Compose short excerpts that use varied musical textures.

- Employ compositional techniques based on salient aural features.

[ 18 ] Assignment #2 takes an alternative approach to assigning points by using a rubric. Grading musical compositions can often be subjective, but rubrics can offer a way to quickly provide an assessment with helpful feedback. Here, each of the two excerpts would get its own rubric assessment, which uses five components over a range of competencies. For each of the two excerpts that the student composes, they can see where they may be falling short, or if they failed to complete one or more components. Although most points (20 of 35) come from the student’s composition, additional points are given for practical tasks such as correct notation. These are to both train students in professionalism, but also to (hopefully) make our jobs easier during the grading process.

Example 6

Assignment #2 Expansion. Set Combinations in Elliott Carter’s String Trio (2011)

[ 19 ] Example 6 shows a way to expand this assignment with more detailed pitch combinations from the String Trio excerpt. While certainly not required, this example could provide another way to connect to the salient aural features of the excerpt for students with some knowledge of basic set theory. Here, a repetitive and unordered three-pitch motive—dubbed an “aural anchor” in the example—combines with four additional discrete trichords. The primary [016] “anchor” of pitch classes F, F[sharp] and B, alternatively combines with trichords [024], [037], [014], each forming an instance of the all-trichord hexachord [012478]. On the fifth combination (with pitches E[flat], G, and A), the pattern breaks, and thus too does the continuation of the salient aural motive in the cello.(2)See Smucker (2015). As part of a presentation on Carter’s music, such details may aid in model composition by providing students with ideas to stimulate their own creative process.

3. Aural Training: Aural Maps and Writing About Music

[ 20 ] The third and final sample assignment is suitable for a course that focuses on prose writing for musicians. For this project, shown in Example 7, students must generate a listening guide and accompanying program notes. The assignment draws on the Chan-Hartley reading described above. Such a project would require the students – many of whom may go on to be educators and performers who work in the public sphere – to think critically about how certain aspects of a piece are worthy of highlighting for the listener. Although the creation of a listening guide might require some technical analysis , the focus would remain on aural facets of the music. This outline has four main categories for the assignment, which again could be expanded as desired. In the first category, students choose the piece for which they will create a listening guide. (Offering a choice of even two options can provide the students with some additional agency and ownership of the project.) The second category asks the student to include certain components in the listening guide. These can be defined prior to or during class periods, or based on the discussion of the Chan-Hartley reading. The third category details the prose writing aspects of the project, while the fourth category provides logistical details.

Example 7

Assignment #3. Visual Listening Guide

[ 21 ] For this project, instructors would define the following learning outcomes for students:

- Distill multiple aural features into a visual or analytical representation.

- Generate prose intended for public engagement.

- Comprehend formal designs of complete pieces or movements in a variety of genres.

[ 22 ] For larger projects with numerous components, we can again turn towards a rubric to help guide our grading, both for meaningful feedback and efficiency of time. Unlike the specific point spread in the assessment file for Assignment #2, the accompanying assessment file for Assignment #3 provides a holistic rubric.(3)I would like to acknowledge my colleagues at Stetson University, Alexander Martin, Shannon Groskreutz, and Lonnie Hevia, who have collaboratively developed and used similar rubrics in our music theory curriculum. While there are seven graded components for the project, they are spread out over five levels of competency (Excellent, Very Good, Good, Fair, and Still Learning). In this rubric, each box lists only general competencies, although these could be expanded for each of the seven components to provide more detailed feedback. The final grade is an average of the seven competency levels.(4)For example, if four components receive “Excellent,” two receive “Very Good,” and one receives “Good,” the resulting grade would be 91.4%, the average of 100, 100, 100, 100, 85, 85, and 70. For larger projects such as this one, a more general compilation of competencies can make things easier for the grader, without sacrificing feedback for the student.

Example 8

Assignment #3. Visual Representation of Elliott Carter’s Clarinet Quintet (2007)

[ 23 ] Depending on how much freedom the student has to define and generate their own terminology, the outcome of this project may produce a wide range of results. The writing components of the project should adhere to college-level writing standards, although the visual listening guide could vary widely. For example, Example 8 offers one possibility of how a two-minute excerpt of Carter’s Clarinet Quintet (2007) might appear as a visual listening guide.

[ 24 ] The alternative pedagogical approaches given here offer ways to engage critically with Carter’s music far beyond the theoretical concept of tempo modulation. They open his music to more general inclusion in a variety of pedagogical settings and potentially shift the narrative of his reception in a broader way. I believe such approaches can provide both relevance for and accessibility to Carter’s music for the future educators, performers, and composers that populate most undergraduate music theory courses.

Footnotes

1. Anecdotally at least this appears to be so: I welcome casual conversations with my former students about their undergraduate experiences in their core music theory courses, and when I ask them about Elliott Carter, I feel fortunate when I get responses like: “He was the tempo modulation guy, right?”

3. I would like to acknowledge my colleagues at Stetson University, Alexander Martin, Shannon Groskreutz, and Lonnie Hevia, who have collaboratively developed and used similar rubrics in our music theory curriculum.

4. For example, if four components receive “Excellent,” two receive “Very Good,” and one receives “Good,” the resulting grade would be 91.4%, the average of 100, 100, 100, 100, 85, 85, and 70.

Works Cited

Benward, Bruce, and J. Timothy Kolosick. 2010. Ear Training: A Technique for Listening. 7th ed., Rev. Boston: McGraw Hill Higher Education.

Berkowitz, Sol, Gabriel Fontrier, Leo Kraft, Perry Goldstein, and Edward M. Smaldone, eds. 2017. A New Approach to Sight Singing. 6th edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Bernard, Jonathan W. 1990. “An Interview With Elliott Carter.” Perspectives of New Music 28 (2): 180–214.

Burstein, L. Poundie, and Joseph N. Straus. 2020. Concise Introduction to Tonal Harmony. Second edition. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Chan-Hartley, Hannah. 2021. “The Visual Listening Guide.” In The Oxford Handbook of Public Music Theory, edited by Daniel J. Jenkins. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197551554.013.26

Clendinning, Jane Piper, and Elizabeth West Marvin. 2021. The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis. Fourth edition. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Holm-Hudson, Kevin. 2017. Music Theory Remixed: A Blended Approach for the Practicing Musician. New York: Oxford University Press.

Karpinski, Gary S., and Richard Kram. 2017. Anthology for Sight Singing. Second edition. New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

Kostka, Stefan M., and Matthew Santa. 2018. Materials and Techniques of Post-Tonal Music. Fifth edition. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kostka, Stefan M., Dorothy Payne, and Byron Almén. 2018. Tonal Harmony: With an Introduction to Post-Tonal Music. Eighth edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

Laitz, Steven G. 2016. The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Theory, Analysis and Listening. Fourth edition. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Murphy, Paul, Joel Phillips, Elizabeth West Marvin, and Jane Piper Clendinning. 2021. The Musician’s Guide to Aural Skills. Ear-Training. Fourth edition. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

Ottman, Robert W., and Nancy Rogers. 2019. Music for Sight Singing. Tenth edition. NY, NY: Pearson.

Roig-Francolí, Miguel A. 2021. Understanding Post-Tonal Music. Second edition. New York: Routledge.

Smucker, Peter Christian Wyse. 2015. “A Listener-Sensitive Analytic Approach to Elliott Carter’s Late Chamber Music, 1990–2012.” Ph.D. dissertation. The University of Chicago.

Straus, Joseph N. 2016. Introduction to Post-Tonal Theory. Fourth edition. New York London: W. W. Norton & Company.