Papers from the Special Session “Elliott Carter: 10 Years On,"

at the AMS/SEM/SMT Joint Annual Meeting, New Orleans, November 10, 2022

The Publication of Elliott Carter’s Epigrams

John Link

Abstract

Elliott Carter completed the draft score of Epigrams for piano trio in September, 2012. But his final illness prevented him from fully reviewing the page proofs of the engraved score, and at the time of his death on November 5th a number of textual questions remained unresolved. This paper is an account of the textual editing that preceded the publication of Carter's final composition.

[ 1 ] Epigrams, for violin, cello, and piano, was Elliott Carter’s last composition, written between April and September 2012. By that Fall, Carter was already looking ahead to his next project. He told Virgil Blackwell that he was reading Marianne Moore with the thought of writing a second song cycle on her poetry, and he told Fred Sherry that he was reading Sappho, an equally intriguing prospect that, alas, was not to be realized.

[ 2 ] Although Epigrams was essentially complete at the time of Carter’s death on November 5th, he had not been able to review the final proofs of the score and thus a number of textual issues were left to be resolved. The piece had been commissioned by the Aldeburgh festival and was scheduled to receive its world premiere in June 2013, so the evaluation of the score was a matter of some urgency. The process was guided by Carter’s manager Virgil Blackwell, his longtime proofreader Allen Edwards, and his editor at Boosey & Hawkes Zizi Mueller, and it involved many of Carter’s friends and colleagues. We all worked with a sense of great responsibility to do right by the piece and its composer, but also with a deep sense of sadness and personal grief.

[ 3 ] After he completed the draft score of Epigrams, Carter followed his usual practice in this period and sent photocopies to Allen Edwards for proofreading. Edwards reviewed five of the piece’s twelve short movements prior to meeting with Carter. In the meantime, Carter had decided on the final ordering of the movements, experimented with quirky titles for them (which he later rejected), and made a few additional edits. After their meeting – at which Carter answered some, but by no means all, of his questions – Edwards updated the proofs of these five movements (nos. I, III, IV, V, and X of the final set) and sent them to Boosey & Hawkes for engraving by David Nadal.

[ 4 ] Carter made a few other edits on additional photocopied pages, but his final illness prevented any further work on the proofs. After Carter’s death, Blackwell sent the last of the composer’s edits to Edwards with a request that he evaluate the feasibility of publishing all twelve movements. Lacking Carter’s resolution of many of his queries, Edwards nevertheless finished marking up the proofs, accompanied by six pages of written commentary, on December 8th. He scrupulously differentiated between edits made “by the composer” and those that reflected his own best judgement, and he cautiously described the proofs an “interpretation.”(1)Edwards’s notes are now in the Elliott Carter Collection of the Paul Sacher Foundation in Basle, Switzerland.

[ 5 ] To resolve the question of whether the piece (or a subset of its movements), was complete enough for performance and publication, Fred Sherry arranged a private reading session at the Juilliard School on February 17, 2013. Sherry played cello, Christopher Otto played violin, and Stephen Gosling was the pianist. Blackwell, Mueller, Edwards, and I attended. The reading session convinced all of us that the piece was not only substantially complete but also of excellent quality, and on February 21, Blackwell wrote to Aldeburgh to say that the full twelve-movement Epigrams would be authorized for the scheduled world premiere. After a follow-up meeting on March 29 performance materials were produced and sent to Aldeburgh, and after the premiere attention turned to the publication of the fine-print edition.

[ 6 ] At that point Virgil Blackwell asked me to review the roughly 100 pages of sketches that Carter made during the composition of Epigrams to see whether they could shed any light on the remaining ambiguities in the score. That the sketches were not consulted earlier is only partially due to the press of events in the aftermath of Carter’s death. More significant is that Carter and Edwards rarely consulted Carter’s sketches during the proofreading and editing of his compositions. Their practice of working only with the most recent set of proofs, whether photocopied or engraved, typically imposes a clear succession of authority on Carter’s manuscripts: The most recent set of proofs typically supersedes all previous states, including the autograph score and the sketches. Thus, it is not surprising that after Carter’s death, Edwards and Blackwell kept to the editorial procedures that had been in place during Carter’s lifetime, although they did solicit input from colleagues who had worked closely with Carter, including Oliver Knussen, Ursula Oppens, and Fred Sherry.

[ 7 ] But the sketches turned out to be of enormous value. In many cases they confirmed the readings that Edwards had proposed – vividly illustrating his deep understanding of Carter’s style and working methods. But in several cases, the sketches brought to light new evidence that pointed to alternative readings, not all of which were included in the published score. They illustrate both the promise and the peril of working with sketch materials in textual editing.

Epigrams VII

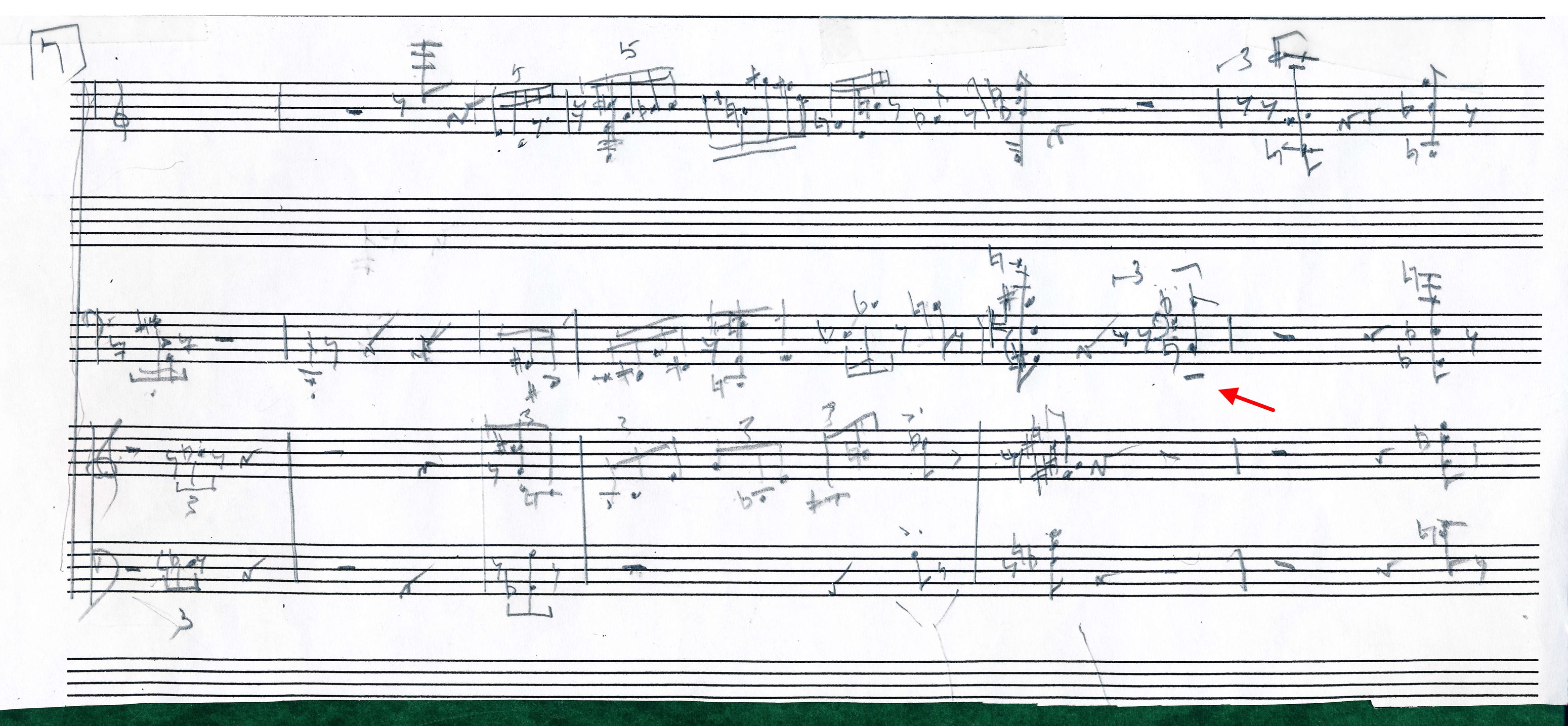

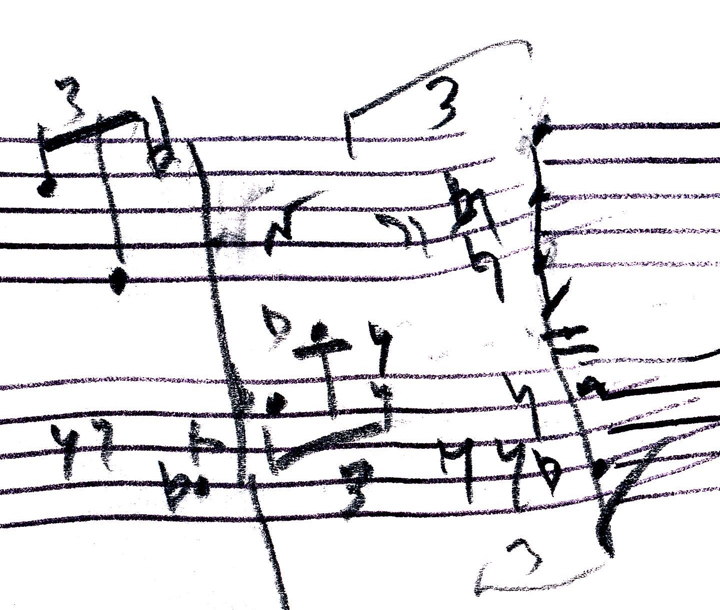

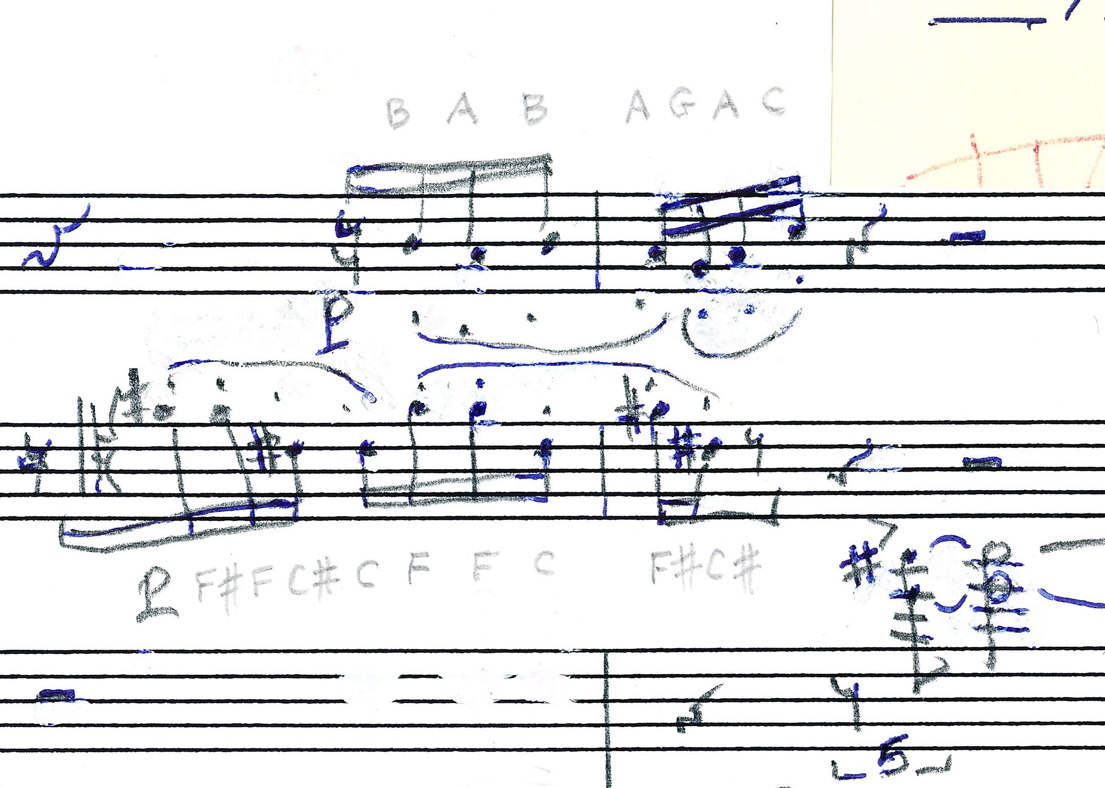

[ 8 ] In Epigrams VII, the strings are pizzicato throughout. But the published score has a somewhat puzzling footnote: “Based on an initial textual reading, later superseded, violin and violoncello were believed to be arco from beat 3 of m. 10 through the downbeat of beat 3 in m. 13.” The basis for this belief was a single mark in the autograph, shown with an arrow in Example 1.

Example 1

Epigrams VII, mm. 7-11, autograph score

Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation. Used by permission.

[ 9 ] In his notes, Edwards explained that he had interpreted this mark as a tenuto dash and wrote “This suggests that the composer was thinking ‘arco’ in this measure – plausibly for both stringed instruments, as a sectional marker.” At the Juilliard reading session, the players tried out the change to arco and liked what they heard. It was subsequently added to the performing materials that were used for the Aldeburgh premiere, for the memorial concert at Juilliard on May 22nd, and for a performance by the Birmingham Group for Contemporary Music at the Library of Congress in April 2014.

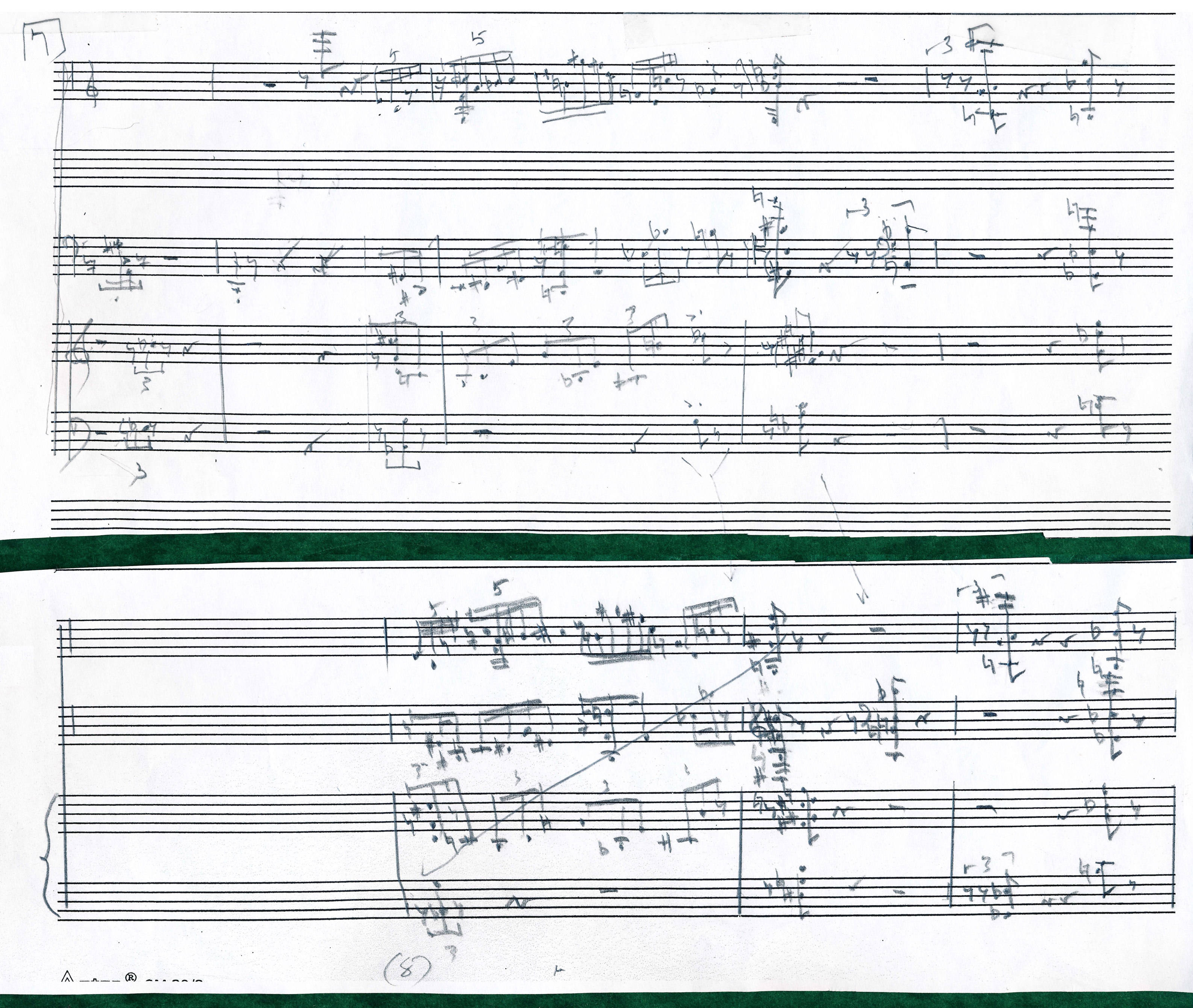

[ 10 ] By the time of the premiere, the momentum for a change to arco in these measures was quite strong. It was thus something of a surprise to find among Carter’s sketches a system that he had cut from the bottom of the score page in question. When this system is viewed in its original context, a very different picture emerges (see Ex. 2).

Example 2

Epigrams VII, mm. 7-11, autograph score, with cut-away sketch page

Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation. Used by permission.

[ 11 ] The chronology here is not certain, but it appears that after writing the upper system, Carter thought to add a beat of rest in m. 8, to add space between the violin’s E6 and the following tutti outburst. That gave the measure five beats, so Carter added a light barline before the last beat. Then he decided to rewrite the following measures on the system below, using a heavier pencil, with the tutti outburst on the downbeat of m. 9. To compensate for the added beat, Carter omitted the fourth beat of the old m. 9, but then drew an arrow to the end of the new m. 9 to show where he thought to reinsert it. That would push back the chords on the downbeat of m. 10 (indicated by his second arrow). At that point Carter changed his mind. He drew a diagonal line through the bottom system and abandoned the possible revision.

[ 12 ] Nevertheless, it appears that one detail from the alternate passage – the isolated cello quadruple-stop in the second-to-last measure – almost made it into the upper system, where the chord has only the top two notes – a double-stop: C3-B♭3. Carter added a ledger line below the staff for the E3, using the same heavier pencil seen in the alternate version. But then he had second thoughts and the ledger line, abandoned but not erased, was left behind. This abandoned ledger line, misread as a tenuto dash, turned out to be the only evidence for a change to arco in the central part of Epigrams VII, so the change was deleted from the published score, and a footnote was added, to explain (at least partially) why mm. 10-13 were played arco in the early performances.

Epigrams V

[ 13 ] The resolution of the “arco question” in Epigrams VII has a particularly satisfying narrative arc, complete with a “Eureka” moment when the two halves of the divided score page are reunited, like the two halves of an amulet in a fantasy novel. But not all of the textual issues in Epigrams can be so definitively resolved, even when the chain of textual authority can be established clearly.

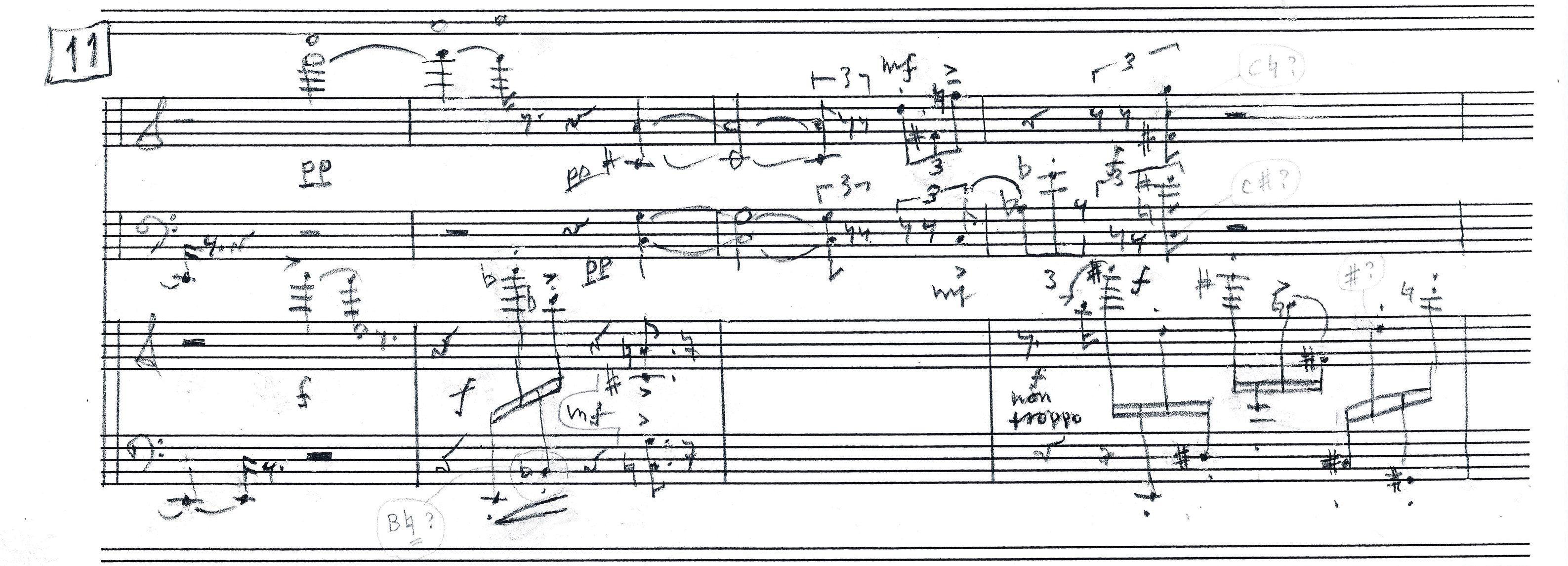

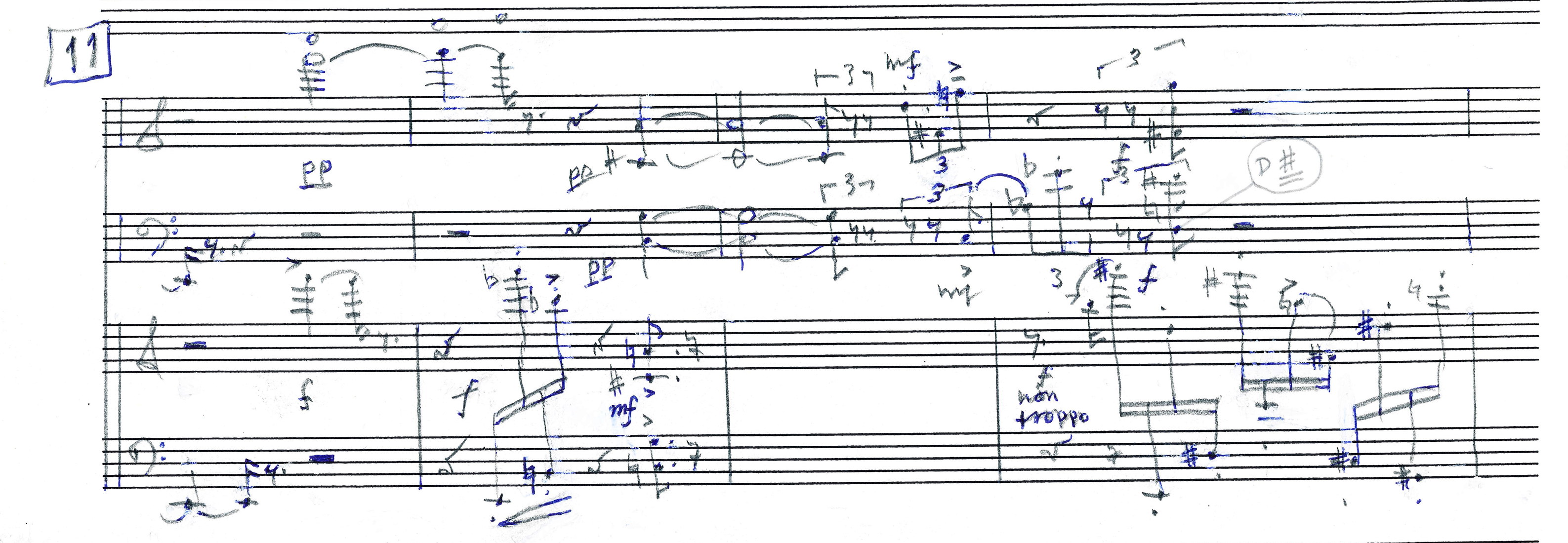

[ 14 ] Reviewing the manuscript of Epigrams V prior to his meeting with Carter, Edwards flagged several problems (see Ex. 3). One of these was the string chord in m. 14, which punctuates a brief piano toccata. Noticing the apparent octave ‘C’s between the bottom note in the cello and the middle note in the violin, Edwards speculated that perhaps Carter meant for the cello to play C♯ and the violin to play C-natural.

Example 3

Epigrams V, mm. 11-14, photocopy of autograph score, with Allen Edwards autograph queries

Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation. Used by permission.

[ 15 ] But in his clean-up of the proofs after Carter’s death, Edwards instead wrote the bottom note of the cello chord on the line above (see Ex. 4). And he made a circled note to the engraver that it should be D♯. This solution reads the note as doubling the piano’s D♯ on the fourth 16th note in beat 2, and this is the version that was used for the published score.

Example 4

Epigrams V, mm. 11-14, photocopy of autograph score, with Edwards’s autograph markings

Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation. Used by permission.

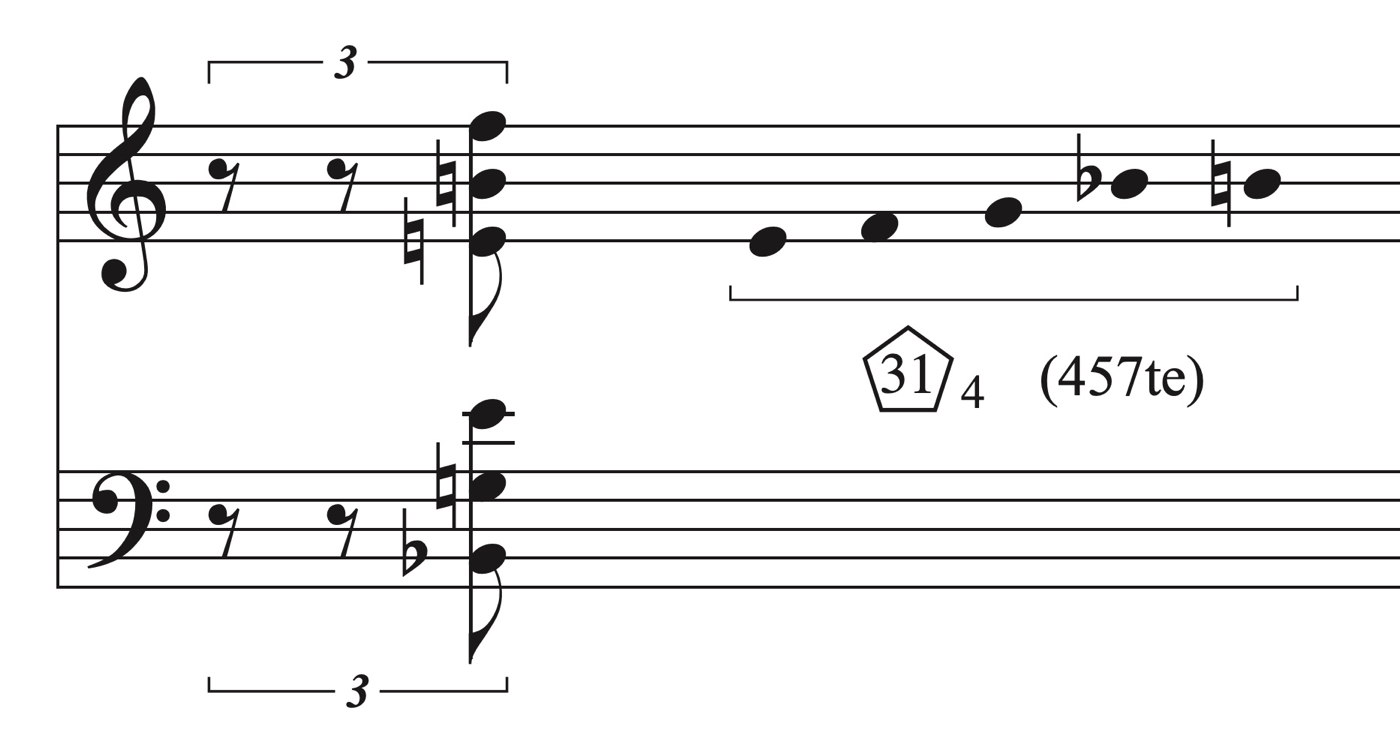

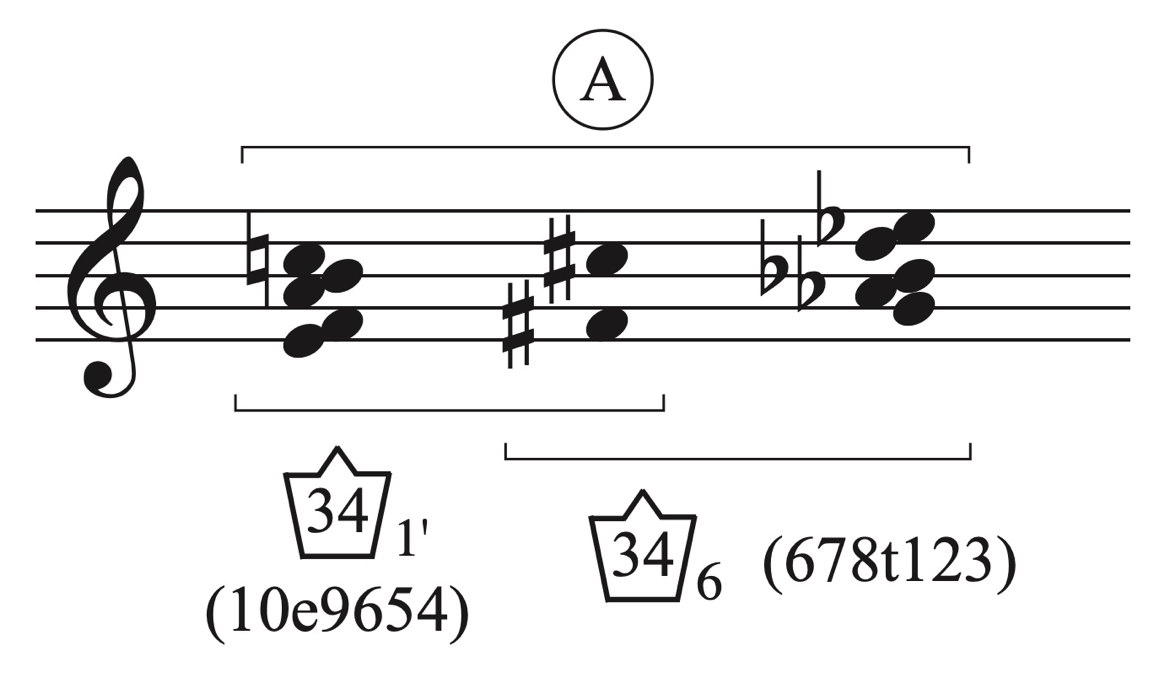

[ 16 ] Here again, the sketches point to a different reading. Carter initially wrote this passage two semitones lower, in a sketch dated April 25th, 2012, shown in Ex. 5.

Example 5

Epigrams V, mm. 11-14, autograph sketch

Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation. Used by permission.

[ 17 ] The string chord in m. 14, marked with an arrow, is B♭2, G3, E4 in the cello and E4, B4, F5 in the violin. Together they form derived core pentachord 31 (01367) (shown on the right side of Ex. 6), a ubiquitous harmony in Carter’s late music and a subset of both the all-trichord hexachord, and of derived core septachord 34 (0124789), which is the harmonic basis for the entire set of Epigrams.(2)See John Link, Elliott Carter’s Late Music (Cambridge University Press, 2022), 53-59. Note that Carter first wrote the middle note of the violin chord as B♭, then overwrote the flat with a natural sign. When he transposed this passage up two semitones for the pencil score, Carter evidently misread the natural as a flat and transposed the note to C, rather than C♯, thus forming the octave with the bottom note of the cello chord, which Edwards quite rightly flagged as a probable error. But Edwards read the cello note, rather than the violin note, as the culprit.

Example 6

Epigrams V, mm. 11-14, autograph sketch (detail) with transcription and harmonic analysis

Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation. Used by permission.

|

|

Epigrams IV

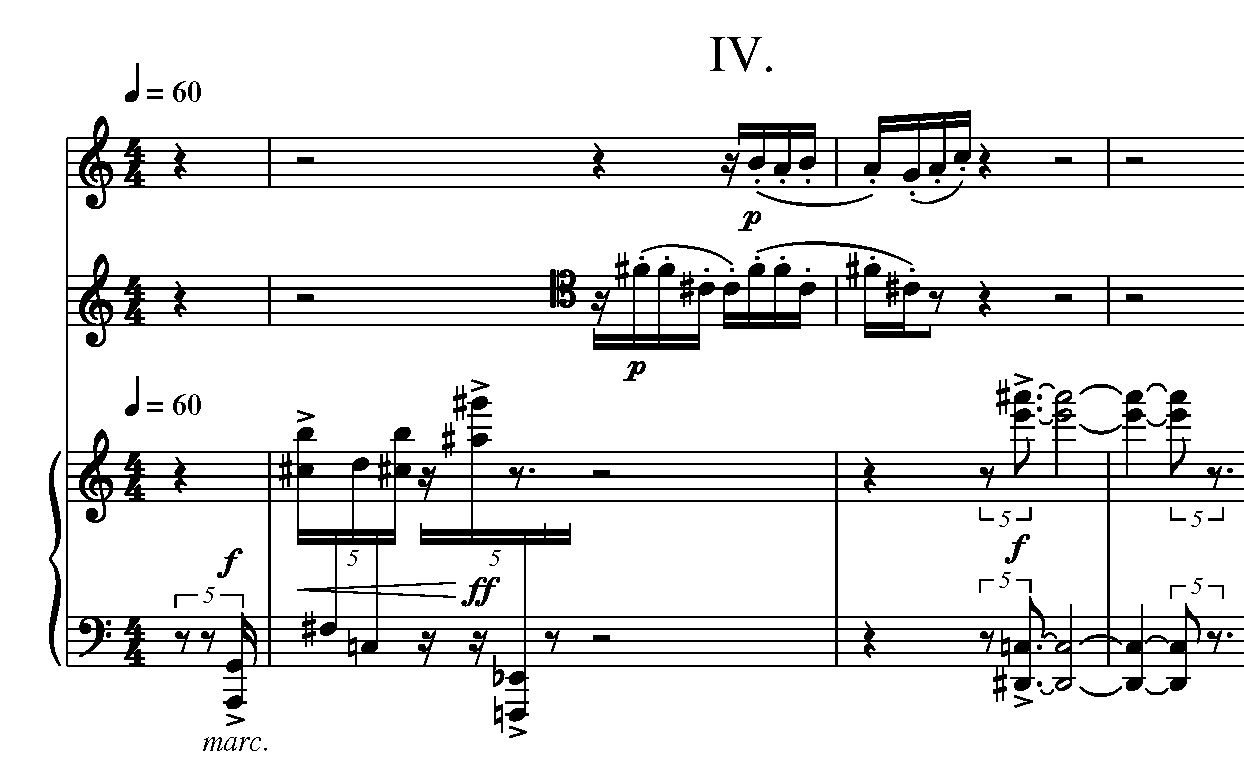

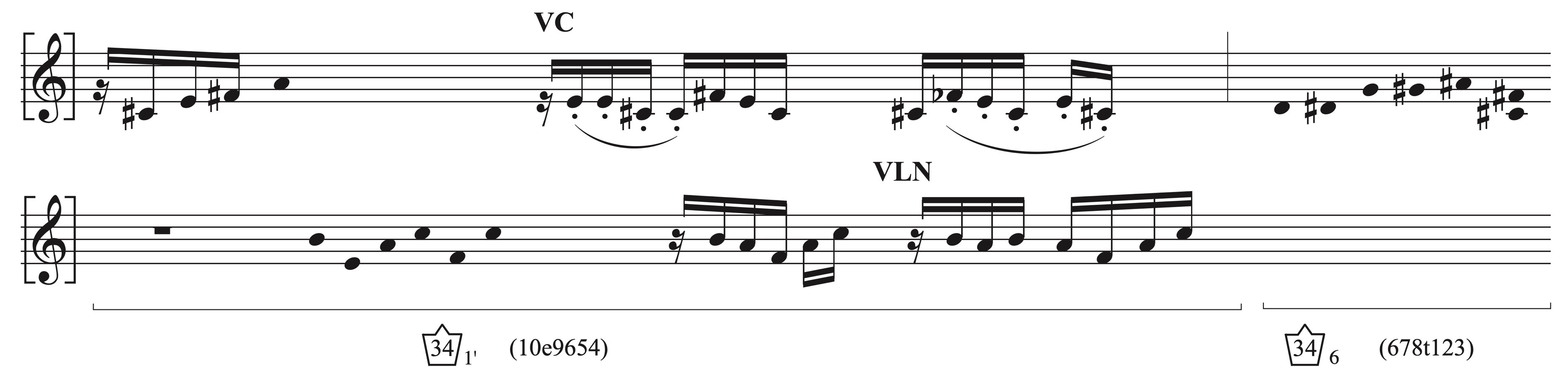

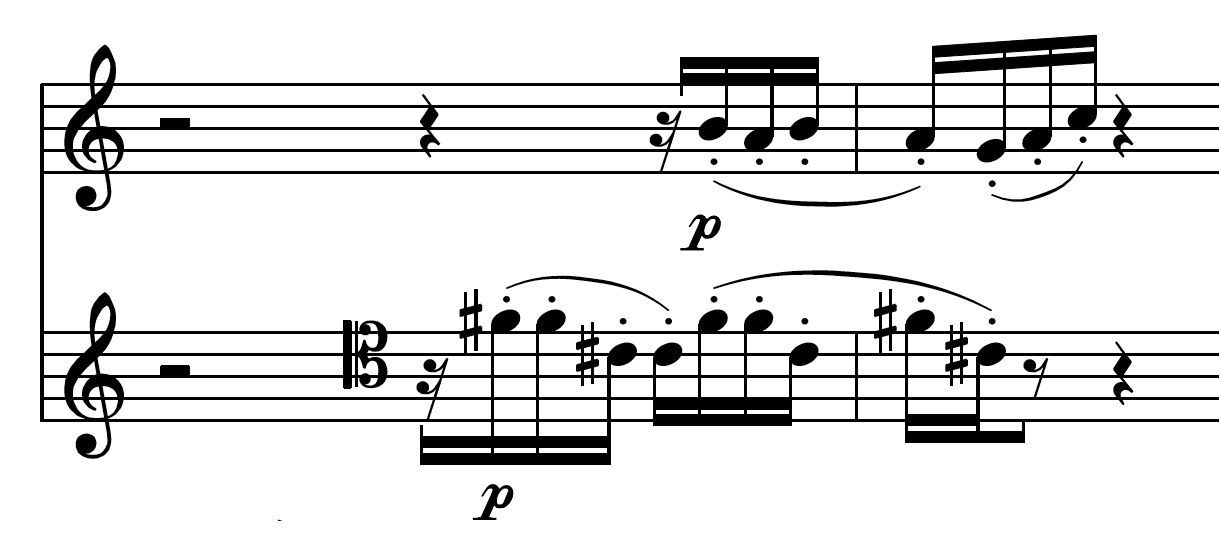

[ 18 ] My last example is from the opening measures of Epigrams IV, where the strings respond to the initial piano flourish with a quiet series of staccato 16th notes (see Ex. 7).

Example 7

Epigrams IV, mm. 1-3, published score

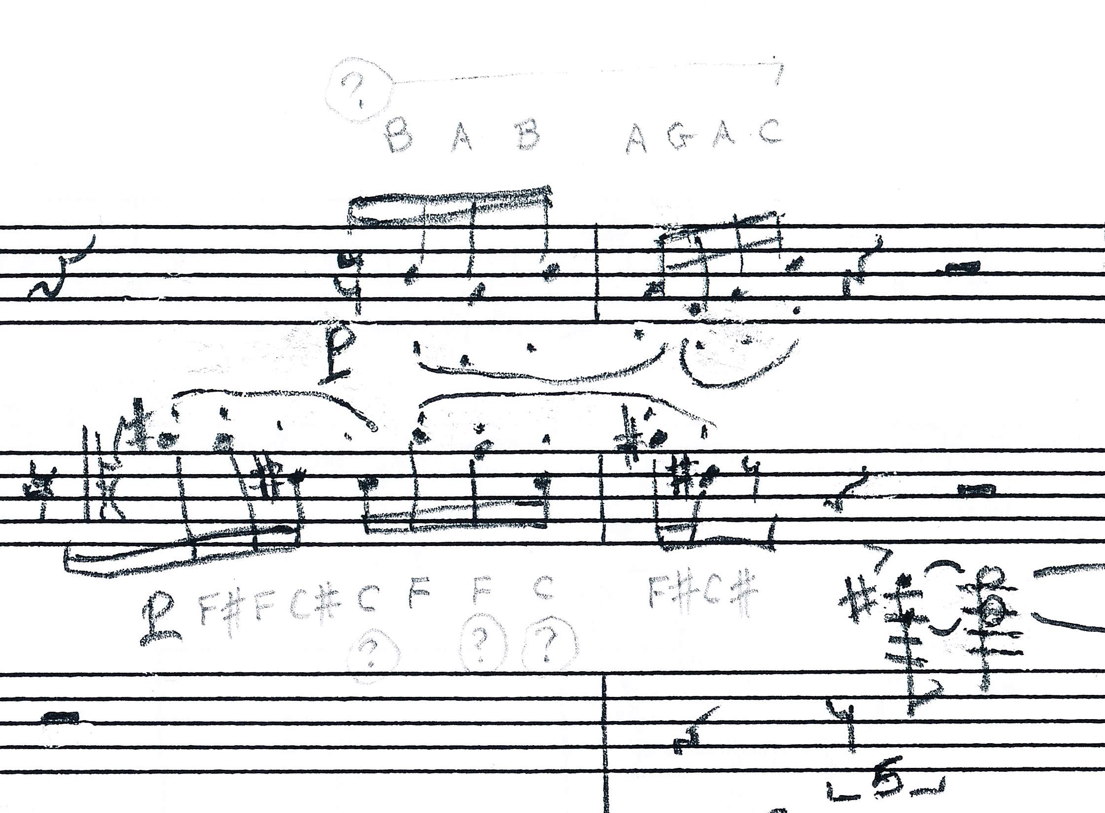

[ 19 ] In Carter’s pencil score, the first pitches in the strings are not entirely clear. When Edwards reviewed this passage, he added letter names for Carter to confirm, and question marks where his uncertainties were greatest (see the left side of Ex. 8). But Carter apparently did not provide answers. Edwards removed the question marks in the proofs he sent to Boosey & Hawkes (shown on the right in Ex. 8), but he made it clear that Carter had not reviewed his reading. In his notes, Edwards wrote that in the last beat of the measure, the cello’s pitches, “are interpreted as C F F C.” Again, the sketches suggest a different reading.

Example 8

Epigrams IV, mm. 1-2,

photocopies of autograph score, with Edwards's autograph queries (left) and markup (right)

Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation. Used by permission.

|

|

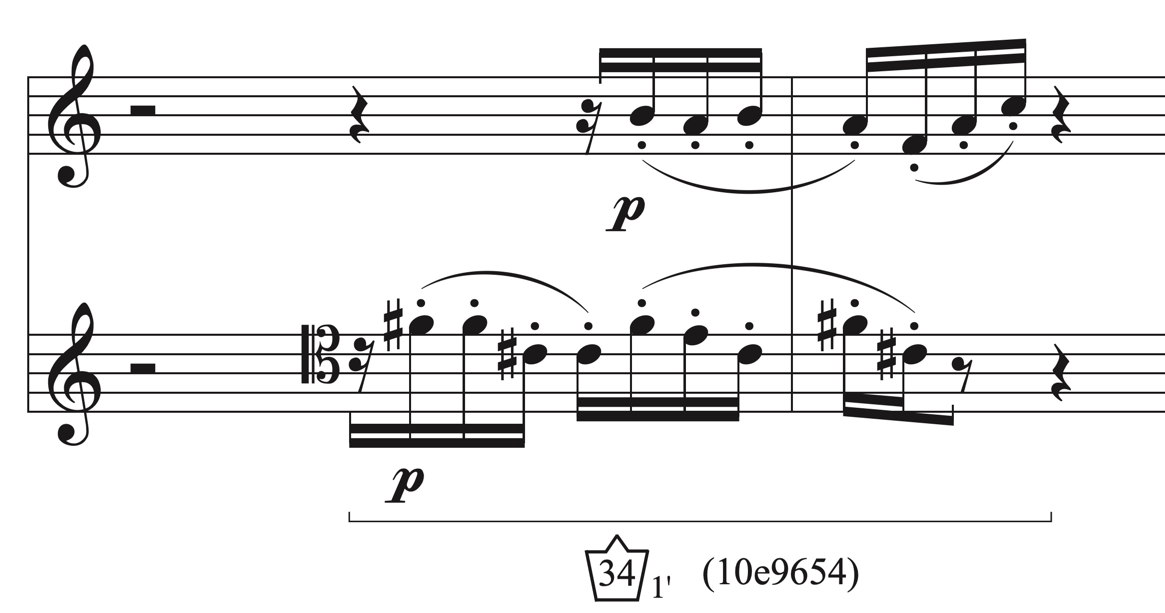

[ 20 ] Carter’s harmonic plan for these measures is inferable from a sketch dated July 20th shown in Ex. 9 with my transcription and harmonic analysis.

Example 9

Epigrams IV, mm. 1-4, autograph sketch and transcription and harmonic analysis

Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation. Used by permission.

[ 21 ] On the top staff, C♯, E, and F♯ are reworked into two additional groups assigned to the cello, while in the lower staff (also with an implied treble clef) B, A, C, and F are notated, and twice reworked for the violin. Together these seven pitch classes form the familiar septachord 34. To the right, on the top staff, Carter wrote the remaining five pitch classes – D, D♯, G, G♯, A♯ – followed by a C♯-F♯ dyad. Together, they form a second septachord 34, and the two septachords complete the aggregate, with C♯ and F♯ as common tones.

[ 22 ] A second sketch, with the same date, shows how Carter realized this passage. (See the left side of Ex. 10.)

Example 10

Epigrams IV, detail from autograph sketch of mm. 1-2 and partial transcription, with harmonic analysis

Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation. Used by permission.

|

|

[ 23 ] Although it is quite rough in places, the sketch clearly confirms the reading I’ve transcribed on the right side of the example, again illustrating the septachord 34 harmony heard throughout the piece. The version in the published score is shown in Ex. 11.

Example 11

Epigrams IV, detail from the published score mm. 1-2

Conclusion

[ 24 ] By the time the fine-print edition of Epigrams was in final review, David Nadal and I were effectively the last people standing. I think everyone felt that they had done their best, and it was time to wrap it up. Allen Edwards had retired, and he made it clear that he had had his final say and that the rest was up to us. He had been the first editor of every new piece by Elliott Carter for more than a decade, and Carter trusted his judgement on editorial matters as he did few others.

[ 25 ] David Nadal and I checked every edit we made with Virgil Blackwell, as Carter’s representative, and Zizi Mueller, then President of Boosey & Hawkes, but by then it was clear that they would support our decisions. And we had then what I’ve shared in this article: compelling textual evidence, supported by harmonic analysis consistent with Carter’s practice, that argued for alternate readings of several key passages. But we couldn’t ignore the meticulous care and sound judgement of not only Allen Edwards but of Carter’s other friends and colleagues as well – Fred Sherry, Ursula Oppens, and Oliver Knussen among them. Their suggestions were informed by decades of experience knowing and working directly with Carter. And they were entirely consistent with the kinds of editorial changes that Carter authorized during his lifetime and even made himself on numerous occasions. Had Carter been able to review every change that Edwards proposed in his “interpretation,” it is very likely he would have approved most of them. Would Carter have preferred the sketch-based readings that I have presented here? We don’t know.

[ 26 ] When we work with primary sources, we have an ethical obligation, not only to strive for textual accuracy, but to respect the people who created those texts, and the contexts in which they worked. When we put words (or notes) into their mouths, we must take the utmost care not to replace their truths – however veiled – with our own.

[ 27 ] Nevertheless, it would be misleading to say that a definitive text of Epigrams is beyond our reach, although in a sense it is: The only person who could resolve the piece’s textual ambiguities definitively is Elliott Carter, and of course he is no longer with us. But, in another sense, we are extraordinarily lucky. By any measure, the score’s textual ambiguities are few, and there are good choices, albeit difficult ones, for resolving them. Like the readings that I have presented here, the readings in the published score not only reflect the love and care of many people who were close to Carter, they are also the product of contrasting voices, engaged in thoughtful, honest, and vigorous debate. And that is perhaps the most valuable lesson that Elliott Carter’s music can teach us.

Footnotes

1. Edwards’s notes are now in the Elliott Carter Collection of the Paul Sacher Foundation in Basle, Switzerland.

2. See John Link, Elliott Carter’s Late Music (Cambridge University Press, 2022), 53-59.

Bibliography

Carter, Elliott. 2014. Epigrams (score). New York: Hendon Music (Boosey & Hawkes).

Link, John. 2022. Elliott Carter’s Late Music. Cambridge University Press.