Metrical Invention in Carter’s Drafts of the Opening Measures of Scrivo in Vento

John Link

I thank Guy Capuzzo for sharing the Scrivo in Vento transcriptions he made at the Paul Sacher Foundation, which inspired this essay.

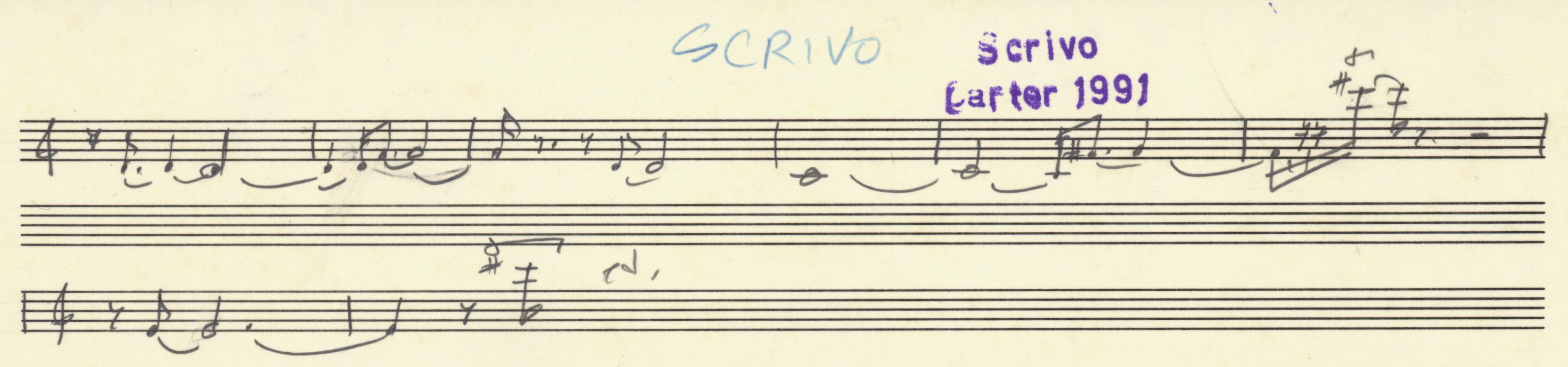

[ 1 ] The 18th Rencontres de la Chartreuse of the Centre Acanthes, in July, 1991, was dedicated to the music of Elliott Carter. This festival, which included concerts, lectures, and master classes, was held in Villeneuve-lès-Avignon, France, largely in the dramatic setting of La Chartreuse, a complex of buildings and ruins that served as a Carthusian monastery during the fourteenth-century reign of the popes in Avignon. Carter composed a short piece for solo flute for the festival – Scrivo in Vento – dedicated to the flutist Robert Aitken, who gave the world premiere on July 6th. The title comes from a sonnet in Petrarch’s “Rerum vulgarium fragmenta” (Fragments of things in the common tongue [i.e. Italian, rather than Latin]), also known as Rime Sparse, or Il Canzoniere. In his program note Carter said that he chose a Petrarchan title because the poet lived in Avignon from 1326-1353. By a happy coincidence the premiere took place on Petrarch’s 687th birthday.

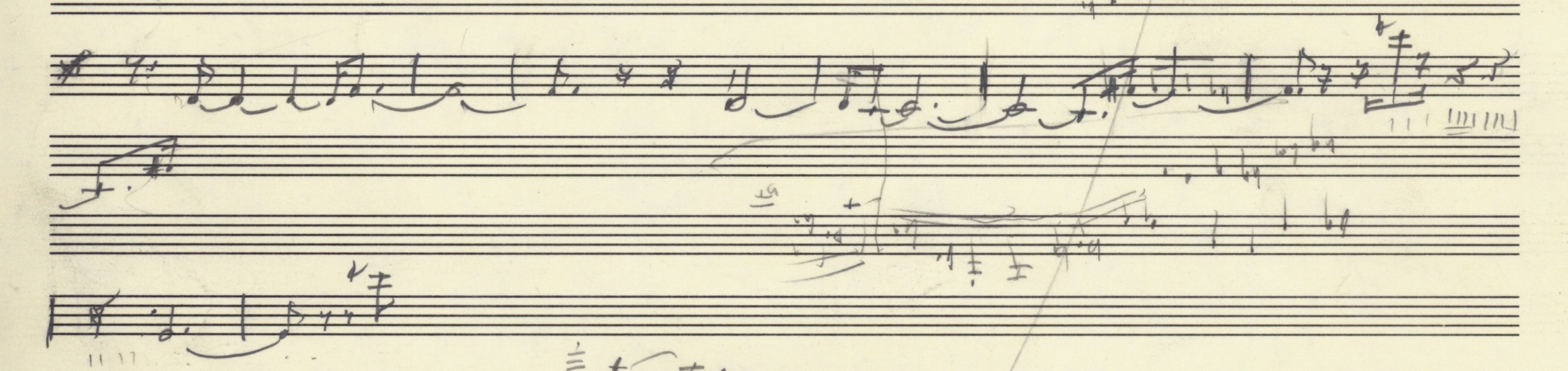

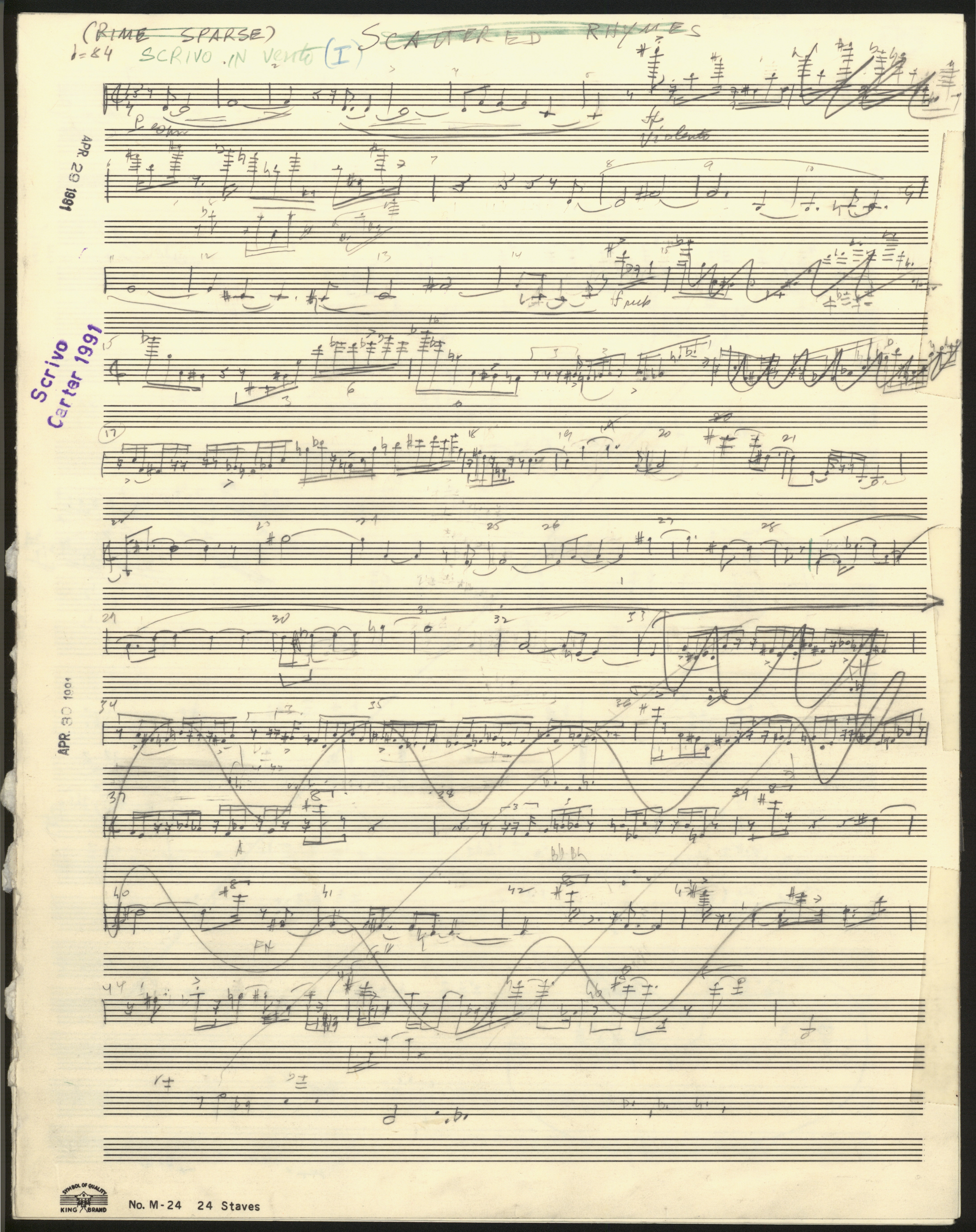

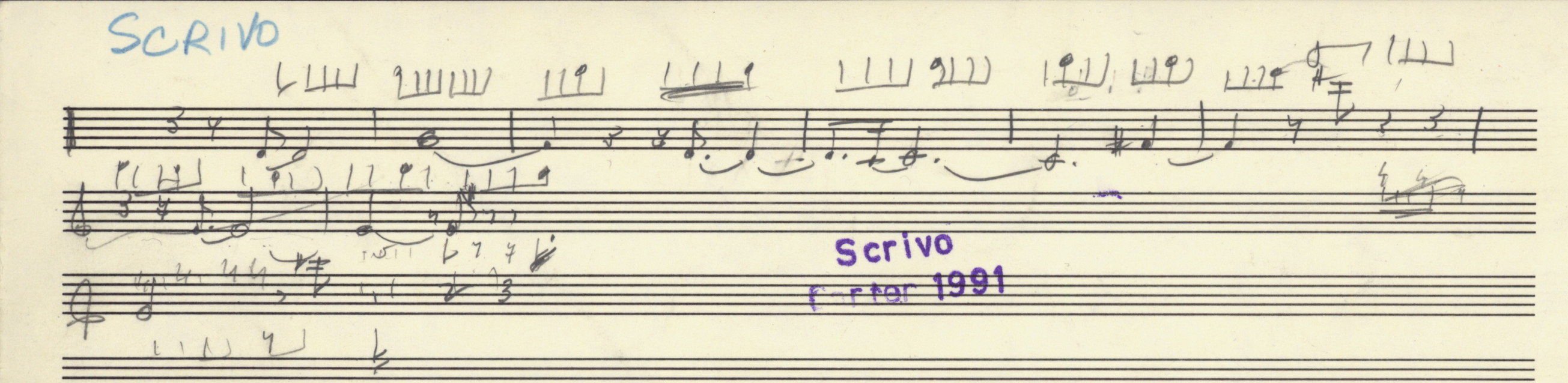

[ 2 ] These associations help to explain the notations at the top of Example 1, from the first page of Carter’s four-page rough draft of the piece. “Scattered Rhymes” is Robert M. Durling’s translation of “Rime Sparse,” and Carter evidently considered both the English and the Italian versions as titles for his piece.(1)See Durling 1976, 36. But he crossed out both of them and wrote in “Scrivo in Vento” (I write on the wind, with a pun on “Scrivo invento” [I write, I invent]).

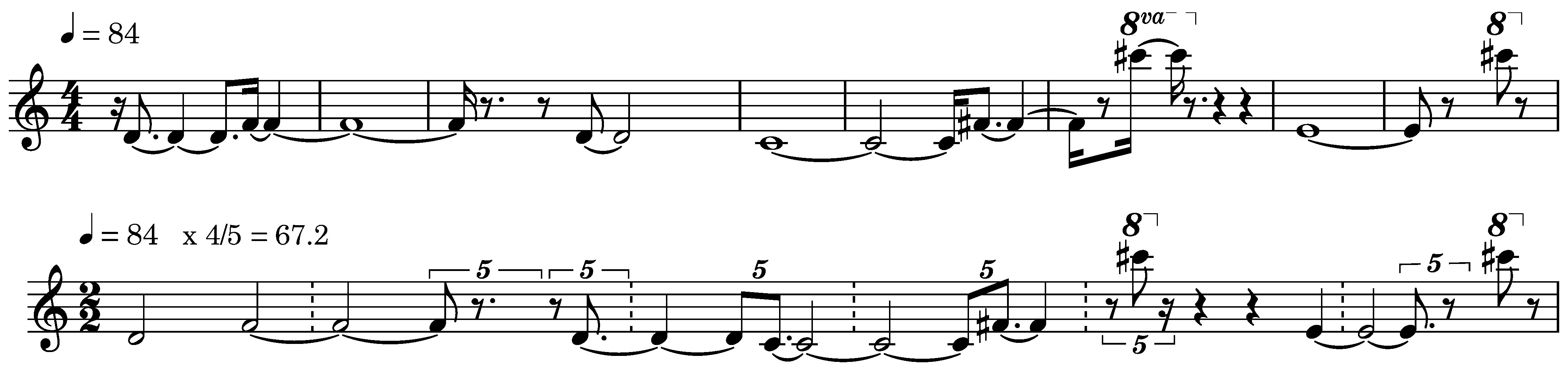

Example 1

Scrivo in Vento, first page of draft 1 (sketch 0315)

Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation, used by permission

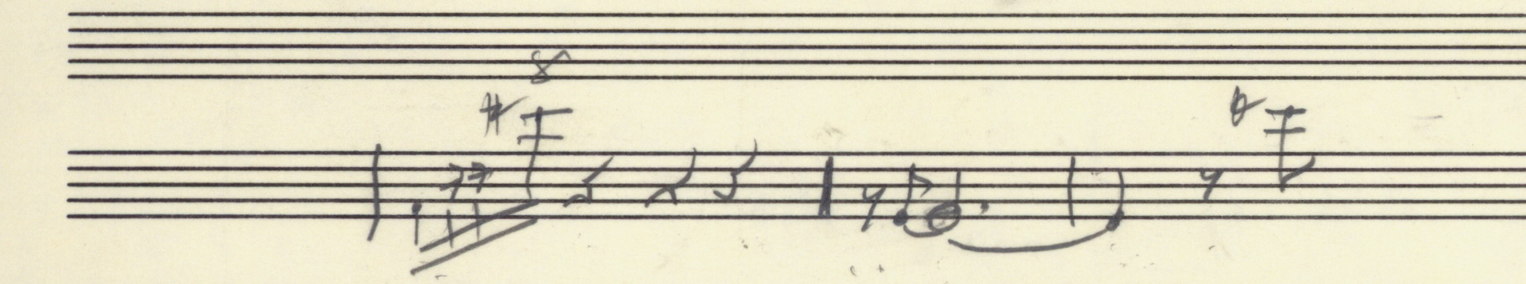

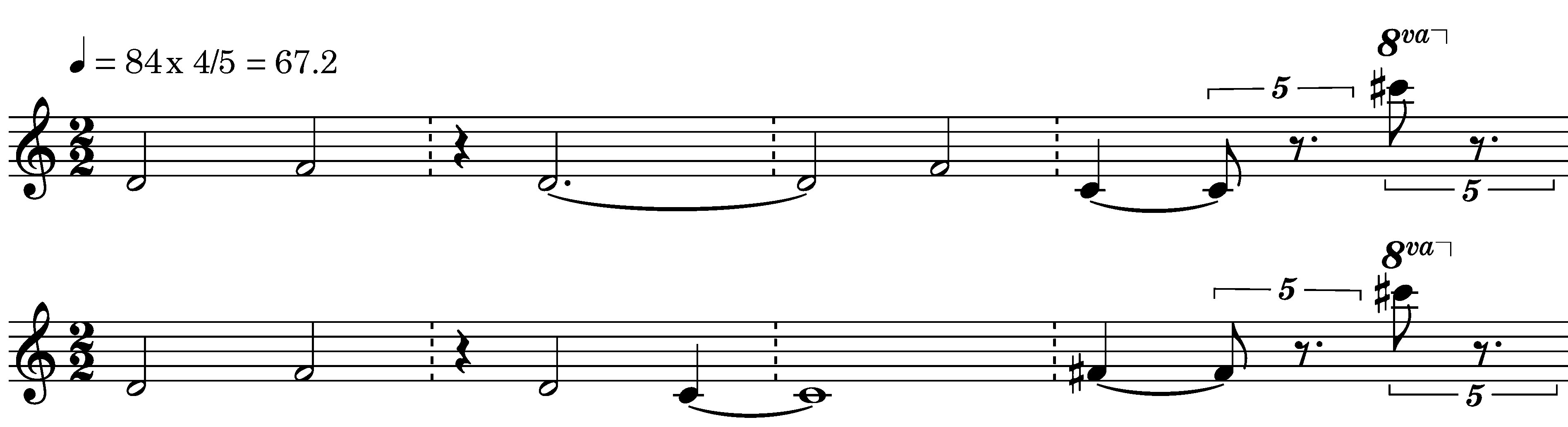

[ 3 ] The opening of the piece, which the published score indicates should be played “not too freely,” juxtaposes two highly contrasting kinds of music: a tranquillo melody that is low, slow, and legato, and a violento outburst that is high, fast, and marcatissimo. Carter made several revisions to his initial draft of this opening. The first one, shown in Example 2, shows a number of significant changes. In place of the (025) trichord at the beginning of Example 1 (D4, F4, C4), Carter substituted a complete statement of the all-interval tetrachord (0146) [0256]. He also added an additional back-and-forth between the two types of music. In the second draft the melody pauses after an isolated C#7 interrupts it in m. 6, then continues with its own single note E4 before the violento music interrupts again.(2)Draft 2 ends with a high C# (in his haste Carter omitted the 8va symbol) to mark where the revised opening connects to its continuation: the violento statement beginning in the last measure of the first staff of draft 1. Draft 2 thus adds to the stark opposition in draft 1 a subtle dovetailing, as though the melody were responding hesitantly to being rudely interrupted, just as a human speaker might do.

Example 2

Scrivo in Vento, draft 2, opening (sketch 0311, staves 1-3)

Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation, used by permission

[ 4 ] With this revision Carter settled on the harmony, texture, and character that the opening passage would have in the finished composition. But as is clear from the two roughly sketched versions of the end of Example 2, some details remained unresolved. To resolve them Carter sketched several additional drafts of these measures, leaving the pitches unchanged but making small, yet consequential, changes to the rhythm.

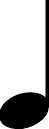

[ 5 ] A clue to the nature of these changes is the pulse stream that Carter notated above the staff in Example 2, with pulses recurring every five eighth notes. Its significance is not immediately clear, as neither the D4 in m. 3, nor the C4 in m. 4 coincides with the stream’s pulses. To clarify the underlying rhythmic organization, I have transcribed the second draft, then re-notated it with the pulses of Carter’s “every-five-eighth-notes” pulse stream falling on half-note beats, and their binary divisions on quarter notes (see Example 3). Because I have reduced the written durations by 4/5 (four eighth notes in my re-notation are equal to five eighths in the sketch) I have also reduced the tempo to 4/5 of the original tempo of  = 84, so that the sounding durations are the same in both versions.

= 84, so that the sounding durations are the same in both versions.

Example 3

Scrivo in Vento, draft 2, opening – transcription and re-notation

[ 6 ] The re-notation in Example 3 makes it easier to see that every attack in the opening measures falls either on a pulse of the main pulse stream or on one of its binary divisions. And because the pulses of the division stream are grouped in pairs by the pulses of the main stream, a sense of metrical organization can be inferred in this passage. The initial D4 and F4 are “on the pulse,” while the following D4 and C4 are “off the pulse,” (i.e. on pulse divisions), creating a syncopation with respect to the pulses of the main stream. The concluding F#4 and C#7 are back “on the pulse.” In the first version of the end of this passage Carter placed the E4 off the pulse as well, but in the second version he moved it one pulse division earlier, so that the last three notes – C#7, E4, and C#7 – occur on three successive pulses of the main stream.(3)Note that the 2/2 meter of my re-notation was chosen for convenience. I assert only the salience of two continuous, nested pulse streams: a “main” stream with pulses every half note (equal to every five eighth notes in Carter’s sketch) and a “division” stream with pulses every quarter note (equal to every five sixteenths in Carter’s notation). I make no claims about the way(s) pulses in the main stream may be grouped.

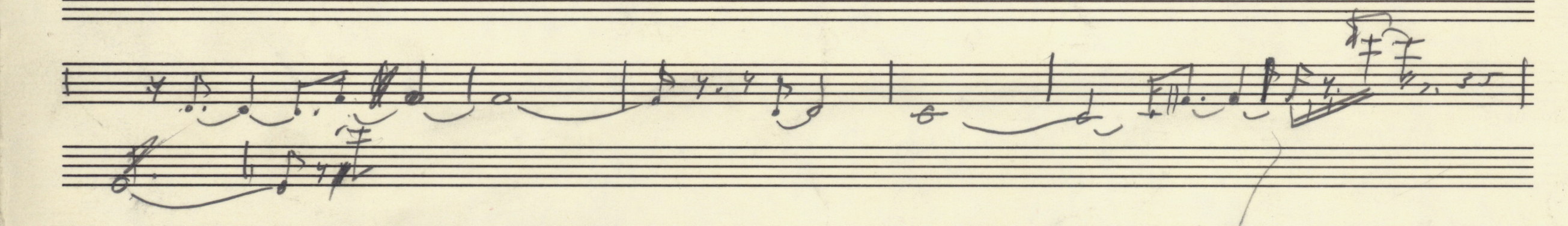

[ 7 ] Carter’s drafts of the Scrivo in Vento opening are all concerned with refining the rhythmic and metrical organization of this passage. If we similarly re-notate Carter’s first draft from Example 1 we can easily compare it to the second draft (see Example 4).

Example 4

Scrivo in Vento, opening measures of drafts 1 and 2, both re-notated at 4/5 the original tempo

Although he revised the harmony, Carter preserved the metrical placement of the first two notes and the last two notes (all of which occur on the pulse), and of the second D4, which is the only note in draft 1 that is syncopated. Its long duration (seven pulse divisions) impedes the momentum generated by the first two notes. And the last three notes fall on successive pulses of the main stream, making the arrival of C#7 somewhat less of a surprise. The second draft corrects both of these shortcomings. The initial upward movement from D4 to F4 (both on the pulse) is balanced by a descent from D4 to C4 (both syncopated). And the longer duration of the second D4 in draft 1 is now assigned to C4, where it breaks up the regular pulses that anticipated the arrival of C#7 in draft 1, instead suggesting a ritardando (two pulse divisions for the second D4, seven for C4), which the arrival of C#7 surprisingly interrupts only two pulse divisions after F#4 sounds.

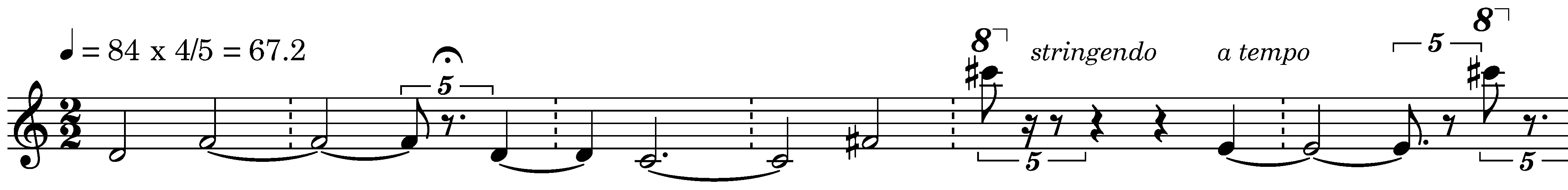

[ 8 ] The re-notations of Carter’s first two drafts illustrate the predominance of the underlying pulse streams. But Carter may have thought that they were too predominant. His third draft, shown in Example 5, introduces a very different kind of rhythmic disruption.

Example 5

Scrivo in Vento, draft 3 (sketch 0311, staves 5-6)

Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation, used by permission

[ 9 ] In this draft Carter shifted the melody to begin five sixteenth notes earlier, but he kept the durations of the D4 in m. 3, and the following C4 and F#4, the same. The only events with new durations are the F4 in m. 1, which is lengthened by an eighth note, and the pause before the E4 in m. 7, which is shortened by the same duration. Example 6 shows a transcription and re-notation of this draft.(4)Note that the change of tempo makes the sixteenth-note beat divisions of the original sketches equal to quintuplet sixteenths in the re-notations. Here we can see that, beginning with the third note, four attacks – on D4, C4, F#4, and C#7 – are delayed by a quintuplet eighth each, after which the E4 and C#7 at the end are both realigned with the pulses of the division stream. The effect is a kind of written-out rubato, with a slight pause before the D4 at the end of m. 2, and a quasi-stringendo before the E4 in m. 5, as shown in Example 7.

Example 6

Scrivo in Vento, draft 3, transcription (upper staff) and re-notation (lower staff)

Example 7

Scrivo in Vento, draft 3, re-notated to show the underlying rubato.

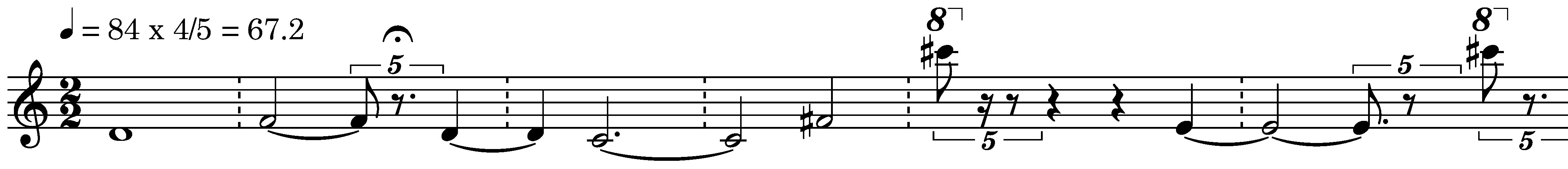

[ 10 ] Draft 3 introduces a fascinating interpretive problem: should the quasi-fermata after the first two notes cause a kind of hemiola in the main pulse stream that is eventually resolved on the E4 (as in the Example 6 re-notation), or should the pulse stream’s fourth pulse simply stretch a little (as in Example 7), as a beat might do in an expressive performance of a similar passage in Chopin or Brahms? Carter’s remaining drafts, shown in Examples 8a, b, and c, are all attempts to resolve this question.

Example 8

Scrivo in Vento, drafts of the opening measures

Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation, used by permission

a) draft 4a (sketch 0311, staves 11-14)

b) draft 4b (sketch 0311, staff 23)

c) draft 5 (sketch 0314, staves 1-3)

Example 9

Scrivo in Vento, drafts 3, 4a, 4b, and 5, re-notated at 4/5 the original tempo

[ 11 ] Example 9 shows re-notations of drafts 3, 4a, 4b, and 5. In draft 4a, the E4 is moved later, so that its metrical position aligns with those of the previous four notes, and the quasi-hemiola is only resolved with the final C#7. Draft 4b is a revision of the ending of draft 4a, which moves the resolution of the quasi-hemiola earlier, to the first C#7. But in draft 5, which he wrote neatly on a separate page, Carter dispensed with the quasi-hemiola altogether. In this version (which matches the published score) the slight pause before the second D4 is interpreted as an expressive stretching of the main pulse stream, rather than as a departure from it. (See Example 10.)

Example 10

Scrivo in Vento, draft 5, re-notated to show the underlying rubato.

[ 12 ] Carter’s drafts of the opening of Scrivo in Vento illustrate how close attention to small rhythmic details can have far-reaching effects on metrical organization and phrasing. It is in this context that Carter’s performance instruction “not too freely” should be understood. Both the expressive pause after the first pair of notes and the implied coordination of the melody with the underlying pulse streams are expressed in terms of the Cartesian grid of the notated beat divisions. They become palpable only when the notated tempo is observed fairly strictly. Of course performers may then choose to adjust their performances in various ways to bring out these details of the composition, but only if they are aware of them.

Footnotes

2. Draft 2 ends with a high C# (in his haste Carter omitted the 8va symbol) to mark where the revised opening connects to its continuation: the violento statement beginning in the last measure of the first staff of draft 1.

3. Note that the 2/2 meter of my re-notation was chosen for convenience. I assert only the salience of two continuous, nested pulse streams: a “main” stream with pulses every half note (equal to every five eighth notes in Carter’s sketch) and a “division” stream with pulses every quarter note (equal to every five sixteenths in Carter’s notation). I make no claims about the way(s) pulses in the main stream may be grouped.

4. Note that the change of tempo makes the sixteenth-note beat divisions of the original sketches equal to quintuplet sixteenths in the re-notations.

Bibliography

Durling, Robert M. 1976. Petrarch's Lyric Poems: The Rime sparse and Other Lyrics. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.