“A whole series of different kinds of inter-relations” in the Second Movement of Carter’s Sonata for Flute, Oboe, Cello and Harpsichord (1952)

Mark Sallmen

Abstract

A diverse set of musical repetitions creates a fascinating web of associations in the second movement of the Sonata for Flute, Oboe, Cello and Harpsichord (1952). Diverse types of themes – several five-pc ordered series, a melody-plus-accompaniment passage and a quartet of dyads – are subjected to varied repetition through transformations such as Tn/TnI, rotation, registral change and fragmentation. Other associations are generated by a network of unordered pcset types, spatial sets, and surface rhythms and gestures. Awareness of these relationships, which run the gamut from near-exact restatement to vestigial recollection, allows larger-scale processes to emerge. Consideration of thematic composing out, transpositional combination, “errors” that are subsequently “corrected,” and thematic fusion and reconciliation all lead to a comprehensive and nuanced view of the movement as a whole.

Building on Randall Shinn’s (1975) analysis of the work, the study widens the scope of inquiry into music of the early 1950s, supplementing the many studies of the First Quartet (1950–51). The paper provides insight into pitch structure in a work created at a time when Carter is exploring post-tonal set types amidst traces of extended tonality that linger from his earlier style. Finally, the essay engages other studies of chamber music that address set-type/human interaction, such as Mailman (2009) and Roeder (2012).

“And this is what I began to think about, from about 1945 or 1948 on… For instance, in my First Quartet, I began to think about how you could have – in the field of counterpoint – you could have one theme being stated and against that another line which would state what the future would be that would then become more important and more highly developed, and another line that would be recalling what you’d heard in the past in a sort of vestigial way. And one could make a whole series of different kinds of inter-relations between the present, the past, and the future within a piece of music.”

—Elliott Carter, 1998(1)Mullis (2018, [27]).

[ 1 ] The “different kinds of inter-relations” that Carter explored in his First Quartet (1950-51) can also be traced in the piece he would compose the following year, the Sonata for Flute, Oboe, Cello and Harpsichord (1952). This study focuses on the second movement of the Sonata, in which passages make multiple references, not only by placing references in different lines, but also by juxtaposing them within the same line, and by fusing them together to create music in which, for example, rhythm suggests one connection and pc content suggests another.

[ 2 ] The large-scale form of the Sonata’s second movement is clear enough: A–B–Coda. In Section A (mm. 69-154) the harpsichord and the instrumental trio each play short fragments that alternate back and forth without overlap.(2)Measure numbers in the movement run from 69 to 202. Section B (mm. 155-178), which David Schiff calls the “jazzy interlude” (Schiff 1998, 115), features tutti instrumentation.(3)For Sylvia Marlowe, who commissioned this work from Carter, jazz and the harpsichord were a routine pairing; she regularly performed in Baroque, pop, jazz and other styles in recital, on the radio, at the Rainbow Room in Rockefeller Center and on recordings (her debut record was entitled “Bach to Boogie-Woogie”). For more on her significant contribution to the resurgence of the harpsichord in mid-century America see Palmer (1989, esp. 110–117). The Coda (mm. 179-202) mixes the textures of Sections A and B.

[ 3 ] But within this clear overall structure there is a complex web of diverse references, a greater understanding of which facilitates an intense, deep, and dynamic hearing of the piece, allowing one to, for example, follow note-to-note coherence within a phrase, identify subtle longer-range references, and sense how instruments continue or interrupt one another’s musical ideas. References run the gamut from near-exact restatement to vestigial recollection. Variation in the clarity of these references arises through transformations such as fragmentation, ornamentation, re-ordering, transposition, inversion and rhythmic/registral alteration. The musical phenomena that create such references are many and varied and have diverse types of identifying features; in Carter’s words, speaking about the Sonata and the Cello Sonata (1948), there are “many kinds of musical characters” (Carter 1969, 228). Some references rely on rhythmic or gestural repetition, such as continuous sixteenths, compound melodies, timbral oscillations and “splashes,” a term I use to denote quick, ten-fingered arpeggiated chords in the harpsichord.(4)Carter uses the term “splashing dramatic gesture” to indicate a different figure that begins the first movement (Carter 1969, 231). Most references, however, rely on pc content.

[ 4 ] The analysis employs unordered, ordered, and partially-ordered pitch-class sets. I use integers to represent pitch classes: 0 = C, 1 = C♯/D♭, and so forth, with “t” and “e” standing for pcs 10 and 11. Curly brackets enclose unordered sets of pitch classes, e.g. {te24}; Forte numbers and prime forms enclosed in square brackets indicate set type, e.g. 4-z15[0146]. Further, following John Link (2019), subscripts without/with a prime marking (′) are used to indicate a particular set’s Tn/TnI relationship to its prime form. (In his labels Link uses Carter’s numbers and shapes to denote set types, not Forte numbers.) For example, three sets of type 4-z15[0146] are: 4-z150 = {0146}, 4-z15t = {te24} and 4-z15t′ = {t964}, which are related to their prime form by T0, Tt and TtI, respectively.

[ 5 ] Ordered sets of pcs are enclosed in angle brackets to indicate ordering from early to late; labels for ordered sets use upper-case letters to indicate Tn/TnI type, along with the subscript of the corresponding unordered set. For example, X7 = <78e1t> is a particular ordering of the pcs in the unordered set {78te1} = 5-10[01346]7. Similarly, X4′ = <430t1> is an ordering of {4310t} = 5-10[01346]4′. The use of X in both X7 and X4′ shows that they are related to one another by Tn/TnI; the 7 and 4′ subscripts are more specific, indicating a TeI relation with one another. I also use subscripted order position numbers enclosed in parentheses to indicate thematic fragmentation and order alteration. Two examples: 123 within X7(123) = <78e> refers to the first three notes of X7 = <78e1t> and 51234 within X4′(51234) = <1430t> refers to the rotation of the fifth note of X4′ = <430t1> to the beginning.

[ 6 ] Depictions of partially-ordered sets use both angle and curly brackets, as with Zt′ = < {58} {t1} {29} {6t} >, which depicts an ordered set of pc dyads, and with Y5′ = { <32e218> <D♭(add9) Fmaj7(♯5)>}, which depicts a six-pc melody and a chord progression.(5)The use of conventional tertian chord symbols is motivated not only by such statements of Y, but also by cadential moments and the jazz-inspired harmony in Section B.

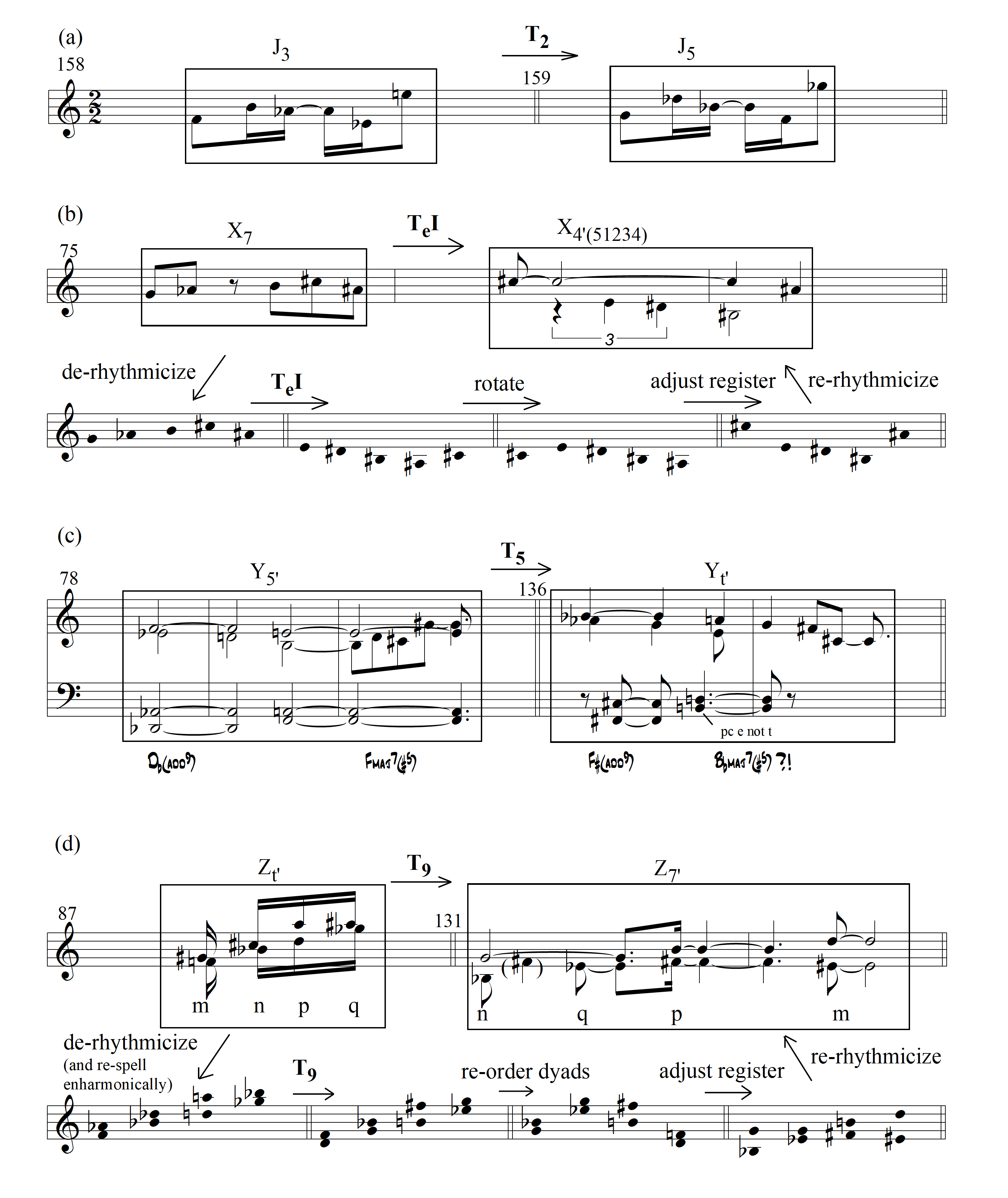

[ 7 ] Pc relations that preserve ordering totally or partially are evident in four primary “themes”: the jazzy interlude’s theme J and Section A’s themes X, Y, Z. These themes differ in their defining characteristics and modes of transformation, in the aural salience of their recurrences, and in the ways their various recurrences enliven the movement’s form. To give a sense of thematic and transformational variety Example 1 introduces the initial statement of each theme and one of its transformations.

Example 1

Primary themes.

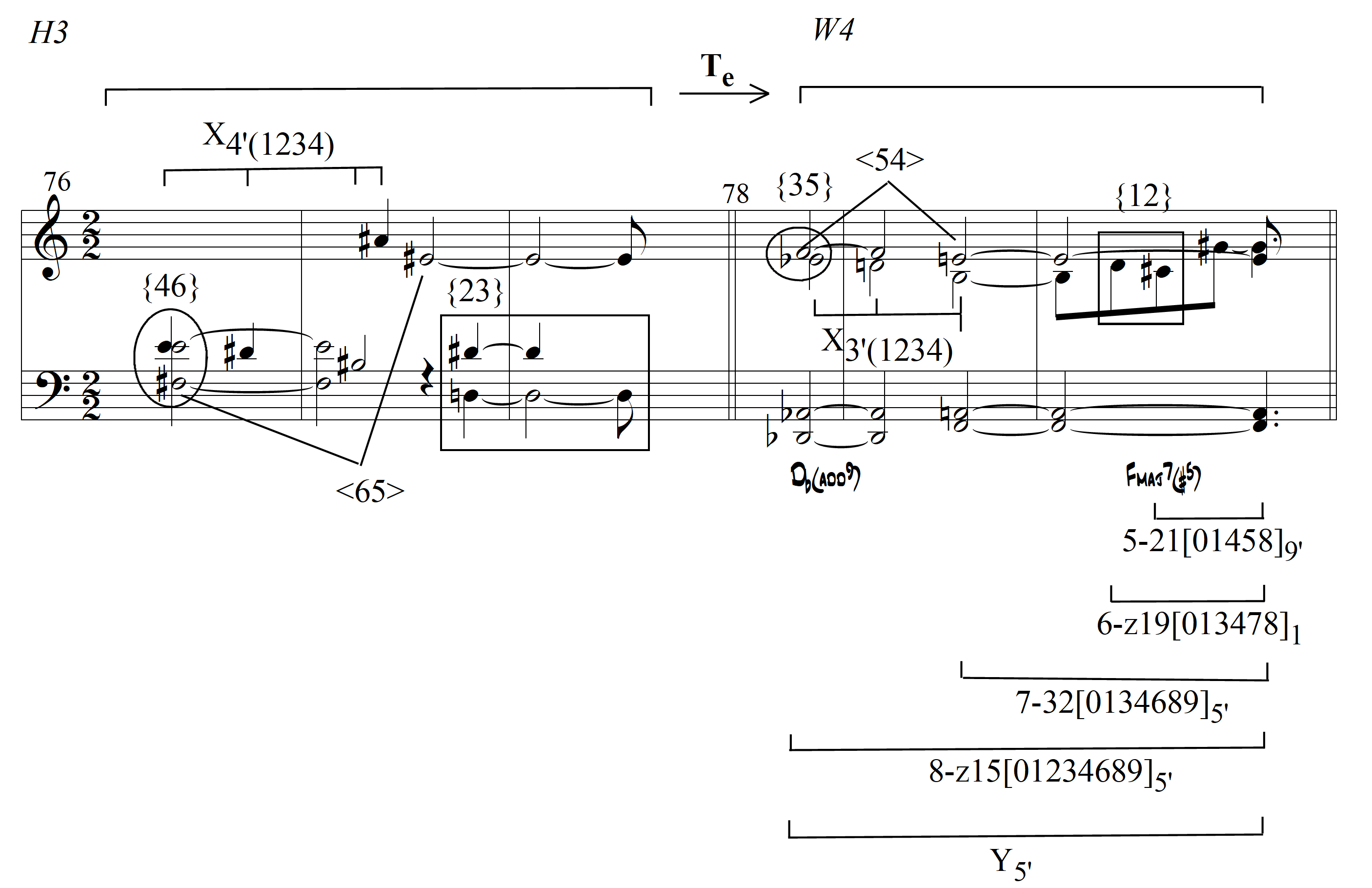

[ 8 ] Example 1(a) shows presentations of J3 = <5e834> and J5 = <71t56>, whose T2 relation is crystal clear due to identical rhythmic presentations and the precise pitch-space transposition of the entire theme up two half steps. This thematic clarity contrasts with the more challenging relations in Example 1(b-d). Example 1(b) shows X7 = <78e1t> and X4′(51234) = <1430t>, whose TeI relation is obscured by rotation and registral and rhythmic adjustment, transformational steps which are depicted on the staff below. Example 1(c) shows Y5′, whose <32e218> oboe melody unfolds over the chord progression <D♭(add9) Fmaj7(♯5)>. The presentation of Yt′ = {<874761> <F♯(add9) Bbmaj7(♯5)?>} transposes most of Y5′ up exactly five half steps in pitch space, but features a more animated rhythm and adjusts the register of the last note of its six-pc melody down an octave. The chordal F♯(add9) is clear but the B♭maj7(♯5) is not. A pc adjustment in the bass (pc ‘e’ instead of ‘t’), along with the altered rhythm of the passage undermines the otherwise clear connection between Y5′ and Yt′. Example 1(d) illustrates the connection of two series of dyads, Zt′ and Z7′. The dyads in Z7′ are T9 copies of those in Zt′ but in a different order and subjected to registral change and rhythmic alteration. Series of lowercase letters on the example track dyadic re-ordering.(6)For example, in Zt′ the ‘m’ dyad is {58}, which appears at the beginning; whereas in Z7′ the ‘m’ dyad is {25}, T9 of {58}, which appears at the end.

[ 9 ] As the analysis will show, a series of radically-transformed versions of X saturate the beginning of Section A1. X7 in particular is a recurring point of reference, appearing at the beginning of the movement, composed out within Section A1, at the beginning of Section B, and several times near the end of the Coda. Within Section A1 the expansive, homophonic Y5′ and the quick sixteenth-note articulation of Zt′ appear separately and create contrast, whereas in Section A3 a series of Y and Z thematic statements gradually reconcile the initial thematic contrast. While X, Y and Z dominate Section A, theme J, with its characteristic jazzy cinquillo rhythm, dominates Section B.(7)The rhythm can be characterized as a cinquillo (2+1+2+1+2) as in Washburne (1997, 59–60) or as a variant of the tresillo (3+3+2 ≈ (2+1)+(2+1)+2)) as in Rahn (1996, 73).

[ 10 ] In addition to such thematic relations, other references are created by spatial sets, such as <[3] [11]>, which denotes pitch intervals 3 and 11 ordered from low to high.(8)Randall Shinn identifies some of the instances of <[3] [11]> that I point to later in the paper (Shinn 1975, 42). In general, Shinn’s analysis, which addresses all three movements, focuses on interval, theme/motive, texture, and form. I build on his comments about the second movement, adding an account of set-type structure and more detailed discussions of theme. This bears a direct relation to Jonathan Bernard’s work with spatial sets; in particular, consulting Carter’s sketch materials for the Piano Concerto, Bernard notes that “the registral arrangement of the trichords could be as important to their identity as is their pc content” (Bernard 1983, 7).

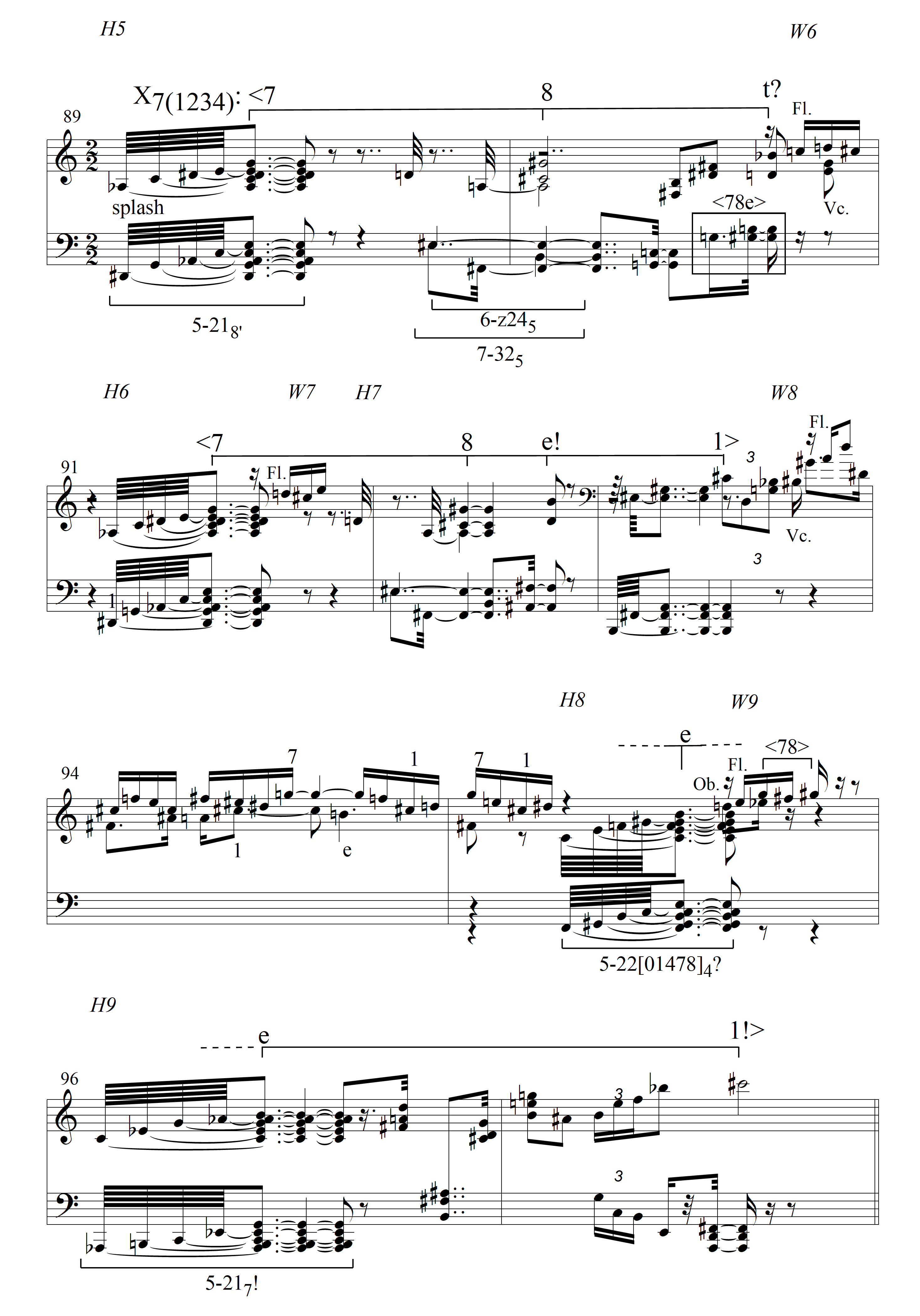

[ 11 ] Relationships among various unordered pcsets provide another layer of organization to the piece. Carter’s notated enumeration of the trichordal subsets of a particular hexachordal set type within the sketch pages for the First Quartet (1950-51) is direct evidence of Carter’s burgeoning interest in pcsets and sub-/super-relationships at this point in his career. My approach also interacts with set-theoretic analysis within accounts of Carter’s contemporaneous pieces. For example, Bernard (1993) studies all-interval tetrachords and their supersets in the First Quartet, Rao (2014) addresses the presence of 4-z15[0146] in the same work, Bernard (1988, 172) identifies set-type repetition in an excerpt from the Cello Sonata (1948), and Nichols (2016) uses recurring set types to relate themes in the Variations for Orchestra (1954-55).

[ 12 ] The pcsets in the analysis are created by considering one vertical slice of the musical texture, by grouping multiple adjacent vertical slices together, and, occasionally, by taking adjacent notes within a single instrument. Such pcsets are related to one another in five ways: 1) set-type identity, in which pcsets related by Tn/TnI articulate the same set type; 2) Z-relations, in which differing set types share the same interval-class vector (ICV); 3) abstract complementation, in which the ICV entries of complementary set types differ by the cardinality difference (and half of that for ic 6); 4) maximal similarity between sets of the same cardinality, in which ICVs share the maximum number of ics that it is possible for non-identical ICVs to share; and 5) abstract subset/superset relations involving sets that differ in cardinality by only one pc. Set-type identity is depicted with Forte labels such as 5-21[01458]. Complement relations are apparent when set cardinalities add to twelve and Forte’s catalog number is the same, as with 5-21 and its complement 7-21[0124589]. Z-relations are identified as the analysis proceeds, the most frequent Z-pair in the movement being 6-z19[013478]/6-z44[012569], a pair that is also central to the pitch organization of Carter’s song “Argument” from A Mirror on Which to Dwell (1976) (Schiff 1998, 174). Maximal similarity is invoked only to relate 5-21 to its ‘look-alike’ set type 5-22[01478], whose interval class vectors are 202420 and 202321, respectively.(9)For maximal similarity consult Morris (2001, 79 and Appendix C page 5). Z-relations, complement relations and subset/superset relations have been explained by, among others, Joseph Straus (2016, 112–123).

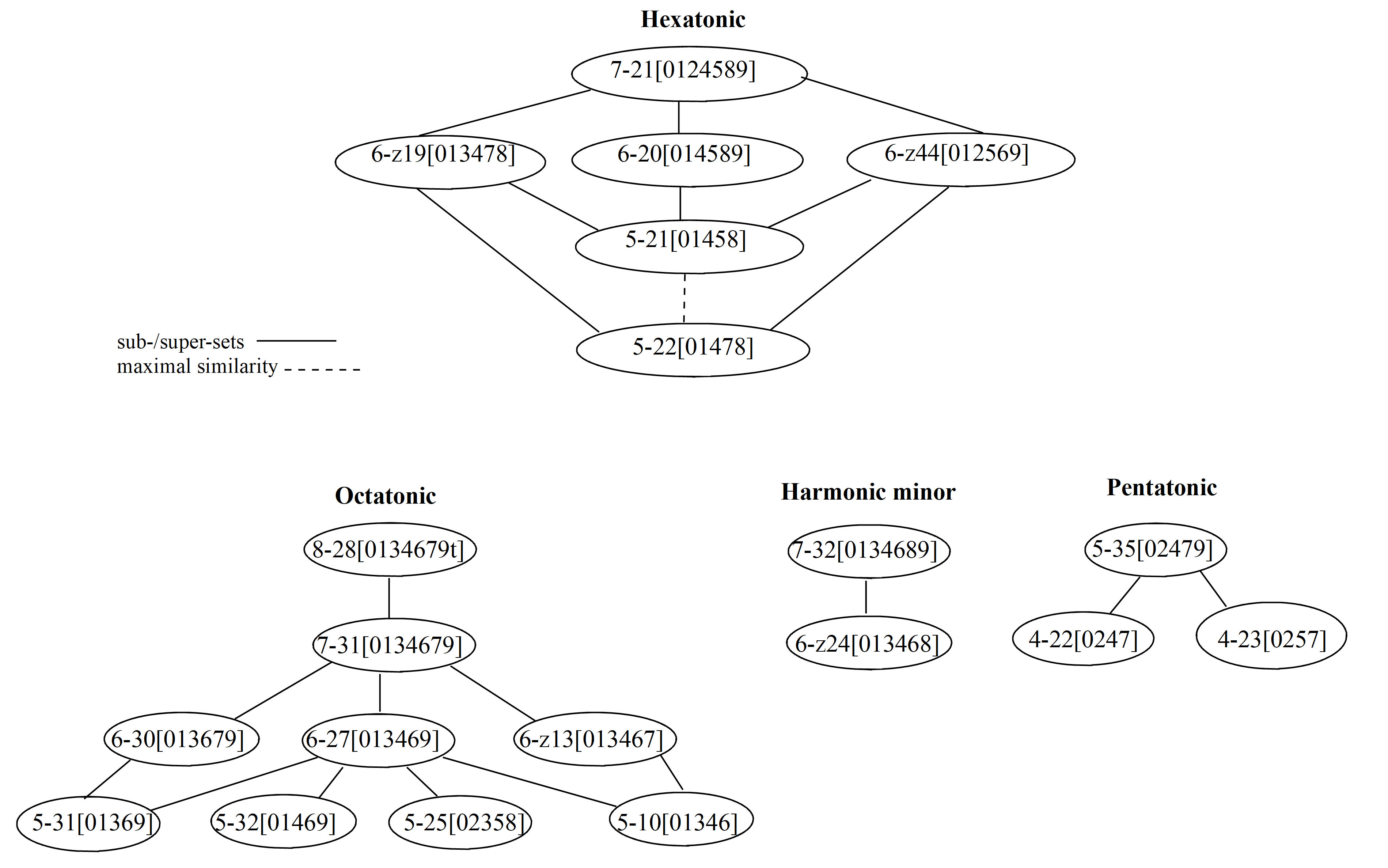

Example 2

Sub-/superset relations.

[ 13 ] In Example 2 solid lines identify subset/superset relations among twenty of the movement’s prominent set types. The relations create four networks. The hexatonic network is primary, featuring the set types that appear most often in the movement: the hexatonic collection itself, 6-20[014589], its superset 7-21 and its subset 5-21, along with 6-z19 and 6-z44, which are both subsets of 7-21 and supersets of 5-21. 5-22 is made an honorary member of this network with the dotted line that indicates its maximal similarity with 5-21.(10)The 7-21/6-20/5-21 relations are particularly interesting. 7-21 has the Complement Union Property (CUP) because the union of any 6-20 and any non-intersecting single note forms an instance of 7-21 (Morris 1990). 5-21 is embedded within 6-20 six times because omitting any note from 6-20 creates 5-21. For more sophisticated applications of CUP in Carter’s music consult Capuzzo (2000) and Roeder (2009). Three secondary networks also invoke familiar extended tonal collections. The octatonic network includes the octatonic collection, 8-28[0134679t], its sole septachordal subset, 7-31[0134679], three hexachords and four pentachords. These set types, for example, dominate the jazz-inspired harmonies at the beginning of Section B.(11)For a discussion of chordal extensions in the diminished scale (a.k.a. the octatonic collection) consult Levine (1995, 78–88, esp. 84). The remaining two networks are simpler. One involves the harmonic minor collection, 7-32[0134689], and its subset, 6-z24[013468], which appear regularly in Section A1. The other consists of the pentatonic collection, 5-35[02479], and two of its tetrachordal subsets, 4-22[0247] and 4-23[0257], which mark points of harmonic repose, especially near the end of Section A3. These networks provide a way to organize salient features of the movement’s complex set-type structure. Overall, thematic transformations such as those in Example 1(b-d) and set-type relations like those shown in Example 2 help to elucidate repetitions of musical material that are near rather than exact. Such analytic flexibility is necessary to bring to light the different types of inter-relations in the Sonata.

[ 14 ] I now turn to a discussion of each section of the second movement in turn. In Section A there are sixty-seven subsections alternating between woowinds-plus-cello trio and harpsichord, and labeled in my analysis W1–H1–W2–H2–W3–… H33–W34. I group these subsections into A1 (W1–H9), A2 (W10–W24), and A3 (H25–W34). The analysis of Section A addresses Sections A1 and A3 in detail and A2 more briefly. A1 introduces X, Y, Z, splash, and various primary and secondary set types. The paper identifies within A2 isolated recollections of earlier material and a series of local relationships within a short excerpt, and within A3 the gradual reconciliation of Y and Z. The analysis treats two excerpts from Section B: the tutti outburst, whose jazzy lines and harmonies lead to J, and a development of J that reveals points of comparison and contrast between Sections A and B. The Coda fuses material from various places in Sections A and B.

Section A1: Introducing X, Y and Z

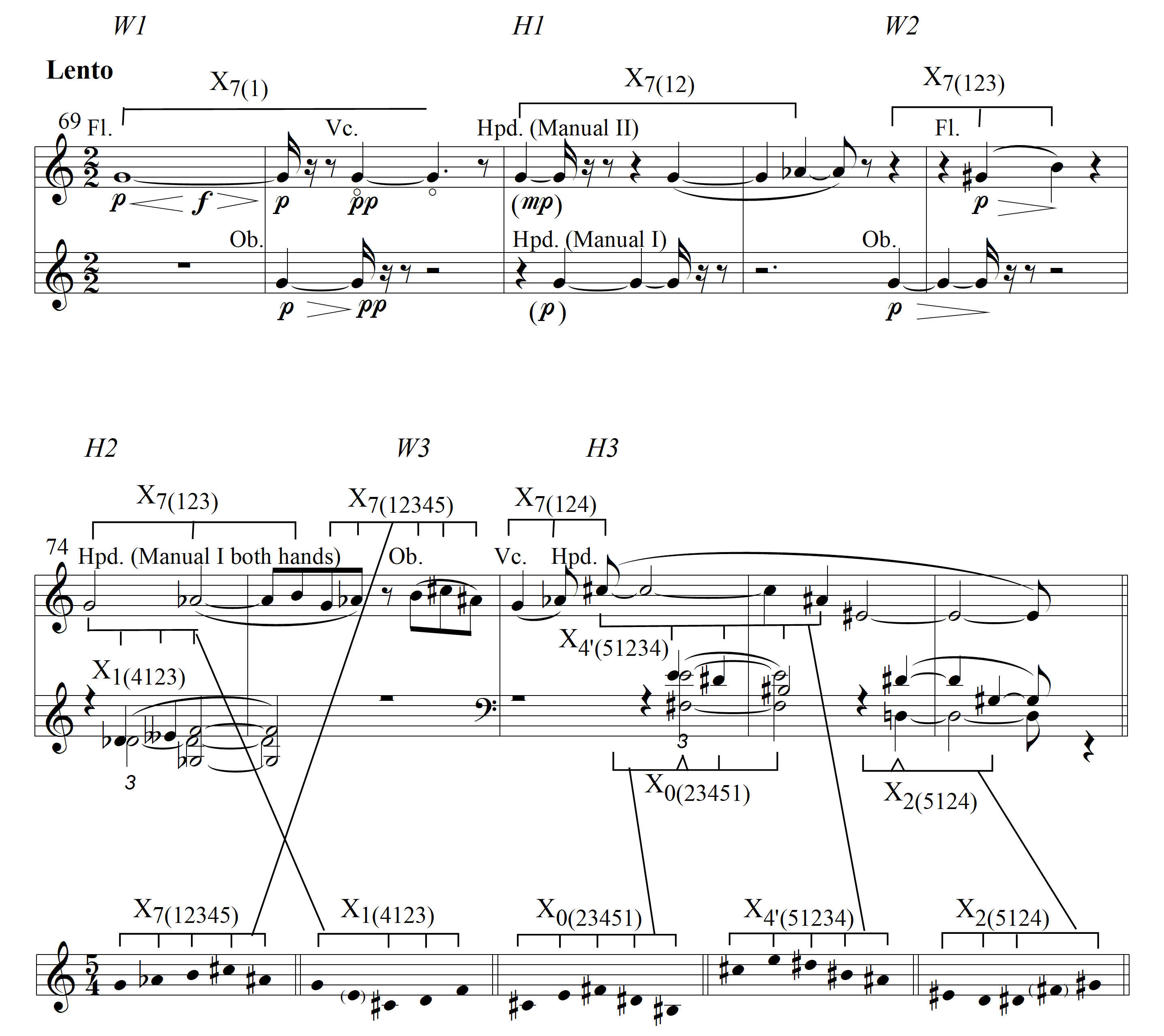

Example 3

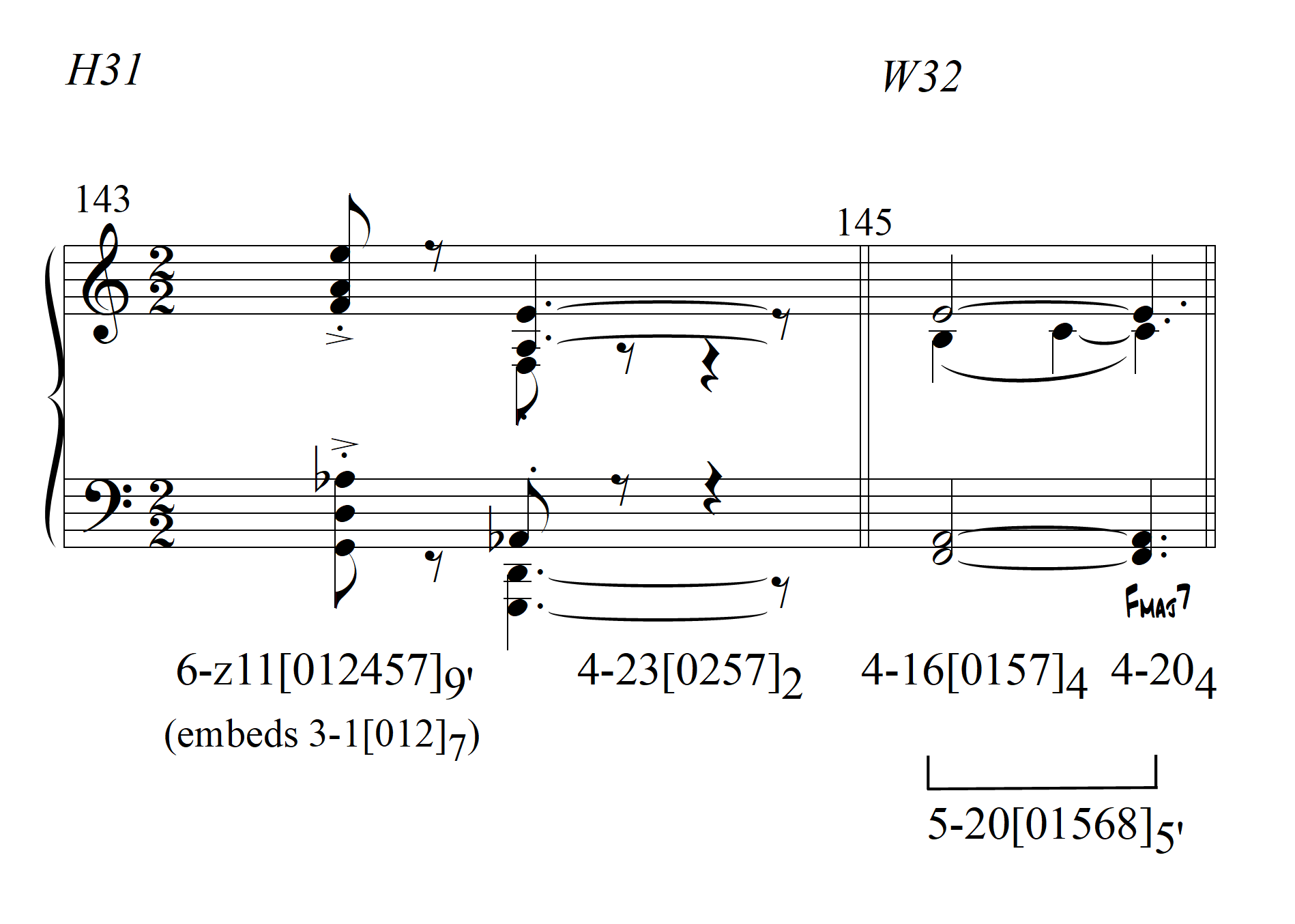

X in H2-H3.

[ 15 ] As shown in Example 3, the opening measures of the movement are dominated by X7 = <78e1t>, whose pcs are introduced gradually: X7(1) in subsection W1, X7(12) in subsection H1, and X7(123) in subsection W2. W1 states pc 7 in flute then oboe then cello, H1 states it thrice more and appends pc 8, and W2 features <78e>.(12)As others have noted, the timbral changes on pitch G4 strongly recall the seventh movement of Eight Etudes and a Fantasy (1950) for Woodwind Quartet (Schiff 1998, 115; Shinn 1975, 39). Randall Shinn views <78e> as globally generative: “The three-note motive, G, G-sharp, B, is extremely important because the intervals involved, particularly the minor third and the minor second, are used in the generation of a great number of motives in the movement” (Shinn 1975, 40). H2 states these pcs again, H2–W3 a complete X7, and W3–H3 another incomplete one, X7(124). Ornamenting and interacting with complete and incomplete statements of X7 are four transformed versions, two complete and two missing a note. In H2, X1(4123) = <7125> arises by combining left-hand <125>, which is a pitch-space transposition of X7(123) = <78e> with right-hand pc 7.(13)The use of an incomplete sequence of order positions in a parenthesized subscript indicates a subset of an ordered set, as with X3′(1234), which is missing the fifth note of X3′. This practice follows Sallmen 2007’s analysis of “In Genesis” from In Sleep, In Thunder (1981). Note that the main theme articulates 5-10[01346] in both works, <78e1t> in the Sonata and <689635> in “In Genesis”. Similarly, in H3, X4′(51234) = <1430t> arises by combining left-hand <430>, which is a pitch-space inversion of X7(123), with right-hand <1t>. At the same time, X0(23451) = <14630> arises by attending to pcs 4 and 6, which are struck simultaneously. The articulation of two complete five-note transformations by a total of only six notes is possible here because of the shared <1430> within both <14630> and <1430t>. H3 concludes with X2(5124) = <5238>, which omits a note, as in X1(4123), includes a simultaneously-struck dyad, as in X0(23451), and begins with order position 5, as in X4′(51234). Despite the complexity there is a certain transformational consistency here because all four additional versions of X involve rotation but not retrograde.

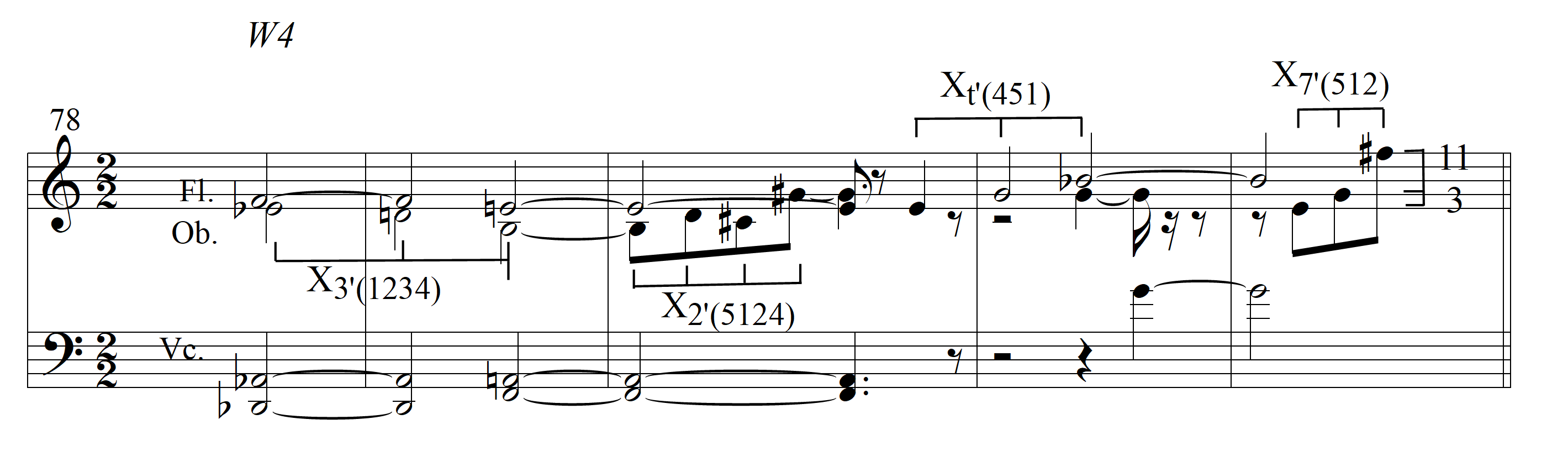

Example 4

X in I4.

[ 16 ] W4 connects to H3 in at least three ways (see Example 4). First, W4 dovetails with H3’s concluding pcs, retaining pcs 3 and 5 at pitch and pc 8 an octave lower, and moving the bass from pc 2 to 1, a minor ninth lower. Second, W4 embeds a series of inverted X fragments, X3′(1234), X2′(5124), Xt′(451) and X7′(512), whose overlapping sets of order positions cycle through X and around to its beginning: 1234, 5124, 451 and 512.(14)Some fragments have multiple possible labels; for example, Xt′(451) = X4(154) and X7′(512) = Xt′(453). X7′(512) provides the first of many articulations of the spatial set <[3] [11]>. Third, as illustrated in Example 5, the first half of W4 seems to be a Te re-composition of most of H3, a relationship that begins with a struck ic 2 in each case (H3’s {46} and W4’s {35}). Similarly, X4′(1234) is echoed at Te by X3′(1234); <65> and its Te transformation, <54>, unfold in a series of measure-long sustained notes; and H3’s {23} dyad is echoed at Te by the oboe’s {12} in W4, a pitch-class relation supported by the overall partial ordering but concealed by pitch interval and harmonic versus melodic presentation. The bass lines of H3 and W4 are related by RTe (<62> and <15>). The first part of W4 is clearly based on H3 but it also takes on a distinct role of its own, as Y5′. Y5′ articulates 8-z15 [01234689]5′, which is the abstract complement of 4-z15, the set type stated by the first four notes of X7.

Example 5

Relating H3 and I4.

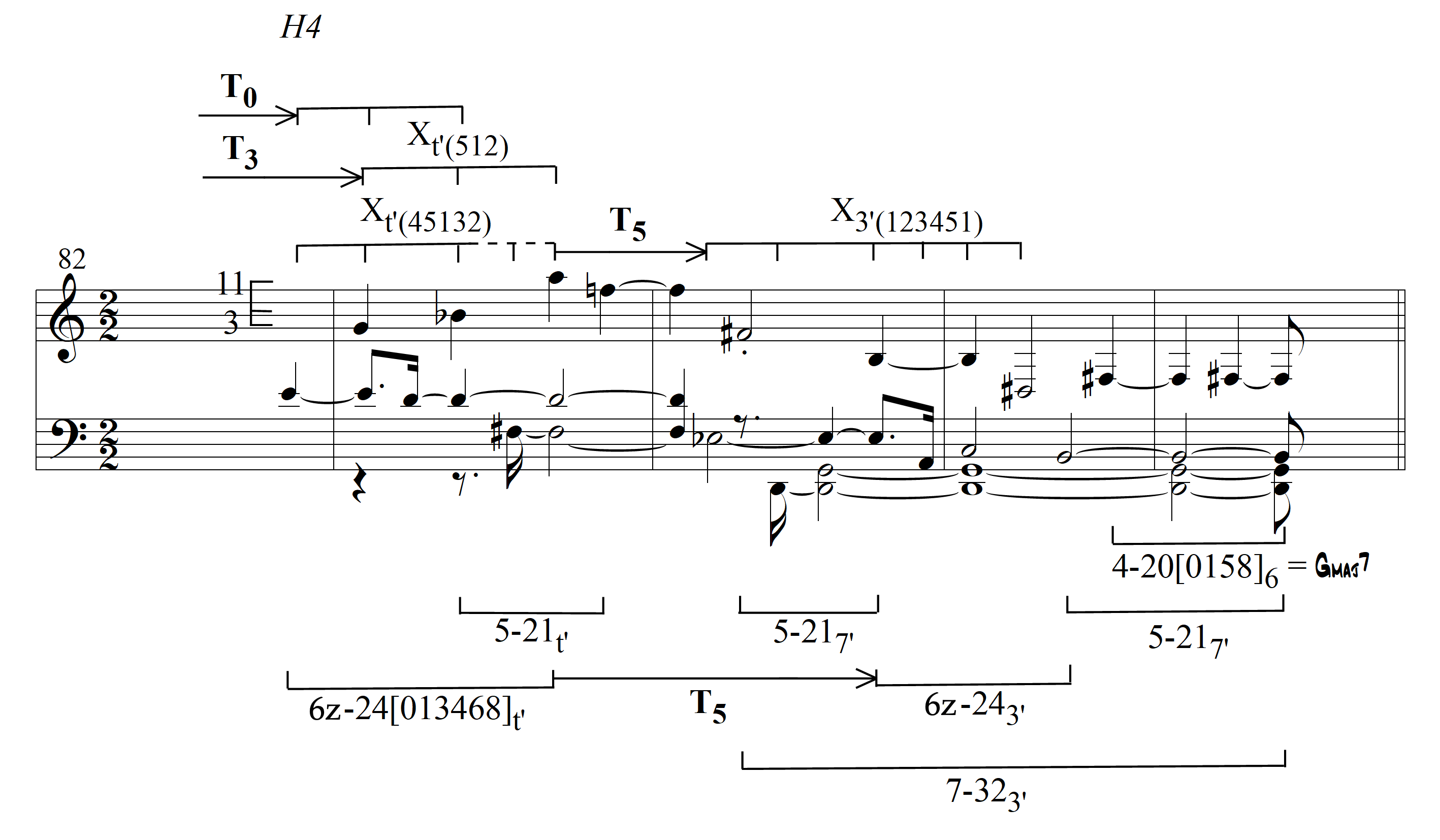

[ 17 ] Theme Y has emerged during material that develops theme X. Development of theme X continues throughout the rest of A1 as other new thematic, harmonic and textural features are introduced. As shown on Example 6, H4 begins with leisurely T0 and T3 references to the second half of W4 that combine to form Xt′(45132), all within the movement’s first 6-z24[013468], 6-z24t′. Xt′(45132) and 6-z24t′ are then recomposed at T5 by X3′(123451) and 6-z243′ in the midst of multiple 5-21s and a 7-32. The passage concludes with a cadential Gmaj7 = 4-20[0158]6.

Example 6

H4.

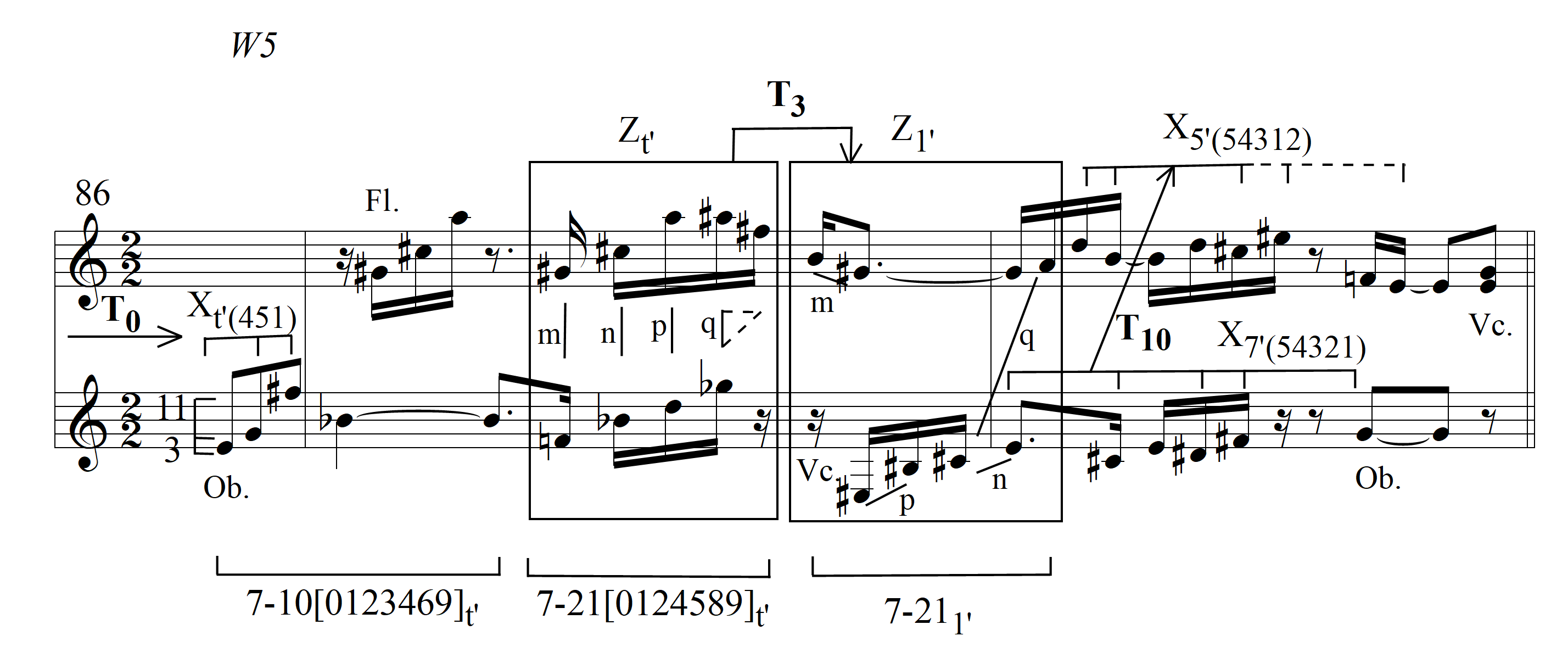

[ 18 ] As shown in Example 7, W5 begins with an exact repetition of the final oboe gesture of W4.(15)This recalls the behavior of the dolce stream within Riconoscenza per Goffredo Petrassi, “…after each interruption by another stream, it recommences by repeating the last few pitches of its previous appearance” (Roeder 2012, 124). This gesture’s contour is then copied, at double-speed by the flute’s <819>, which is then repeated, extended and accompanied by the oboe in similar motion. The resulting quartet of dyads, which articulates 7-21[0124589]t′, is the Zt′ introduced in Example 1 above. Immediately following Zt′ is its T3 copy, Z1′, in which dyads are melodic instead of harmonic, reordered as

Example 7

X and Z in W5.

[ 19 ] The movement’s first harpsichord “splashes” arrive in H5–H9, helping to articulate a linear statement of 4-z15[0146], X7(1234) = <78e1>, which unfolds in the upper notes of the harpsichord part (Example 8).(16)The expression of X7(1234) locally and then over the course of a few phrases engages the notions of motivic enlargement (Alegant and McLean 2001) and composing out (Straus 2004 and 2016, 159–63). The all-interval tetrachord 4-z15 appears often melodically and only occasionally harmonically in the Sonata, a seeming reversal of its use in Carter’s previous work: “My First String Quartet is based on an ‘all-interval’ four-note chord, which is used constantly, both vertically and occasionally as a motive…” (Edwards 1971, 106–107). For further discussion of the role of 4-z15 in the First Quartet see, for example, Bernard (1993) and Rao (2014). 4-z15 is also featured in the “Recitative” and “Canaries” movements of the Eight Pieces for Four Timpani (1950) (Schiff 1998, 133–34). To see the other all-interval tetrachord, 4-z29[0137], in a thematic context consult the analysis of Esprit rude/Esprit doux (1985) by John Roeder (2012, 115–122). 4-z15 and 4-z29 are used in competitive opposition in Scrivo In Vento (Mailman 2009).

Example 8

X7(1234) = <78e1> in H5-H9.

The opening presents <78t>, whose ‘erroneous’ pc t is accompanied by the ‘correct’ <78e> in short durations an octave lower.(17)Speaking about the First Quartet, Schiff characterizes the second violin’s entrance as “mistaken” because the instrument then drops out, waits and begins again (Schiff 1998, 57). The flute is quick to point out the harpsichord’s ‘error’, flaunting pc 1, the final pc of X7(1234). The harpsichord begins again, correcting its earlier error with pc e instead of pc t. <78e1> is completed this time but pc 1’s arrival seems unsatisfying – one octave lower than the rest of the line. The pcs of X7(1234) feature prominently, both in W8 where pc 7 is the longest and highest note of the flute line and pcs 1 and e are the longest and highest notes in the cello (m. 94), and in the flute line of W9, which embeds <78>. In H8 and H9 the harpsichord recaptures pc e atop consecutive splashes, the first of which seems to be another ‘error’, 5-22 instead of 5-21, which is then corrected to 5-217, topped by <78e>. This leads to another arrival on pc 1, the final pc of X7(1234). This arrival feels triumphant because it marks the registral highpoint of the movement so far.

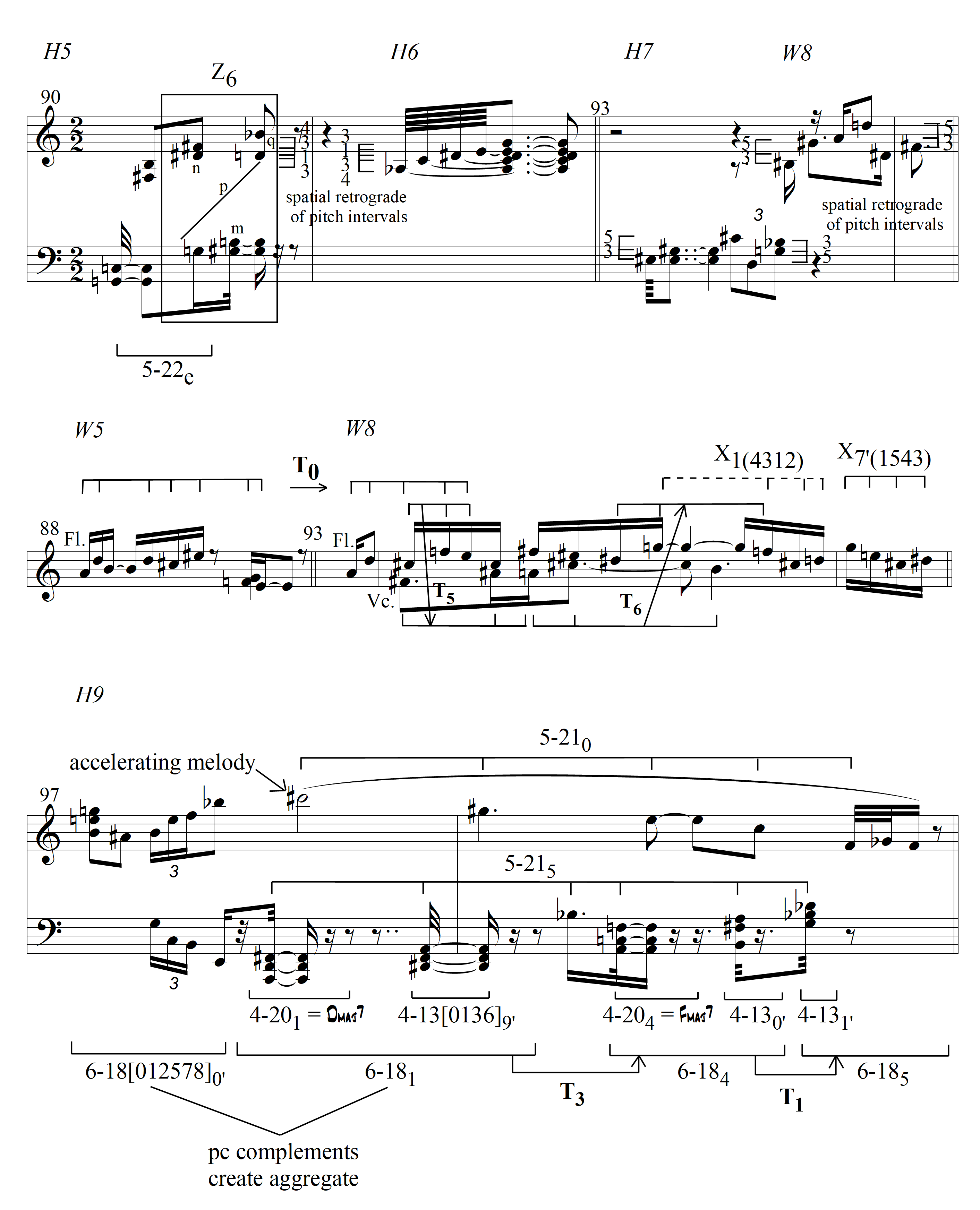

[ 20 ] Four other connections ornament the composing-out of X7(1234). First, the material leading to the harpsichord’s erroneous pc t creates three connections: 5-22e foreshadows the set-type of the later ‘erroneous’ splash, a jumbled Z6 recalls W5, and the right-hand part articulates a spatial set whose intervals appear in retrograde spatial order in the immediately following splash (<[3] [1] [3] [4]> vs. <[4] [3] [1] [3]>). (See H5 and H6 on Example 9.)

Example 9

H5-H9 details.

Second, spatial sets <[3] [5]> and <[5] [3]> create local continuity at the H7–W8 boundary. Third, the W8 flute line begins with <92154>, which summarizes the end of W5 at T0. W8 ends with X1(4312) = <7512> and X7′(1543) = <7413>, whose <75> and <74> fragments recall the very last gesture of W5, where the oboe sustains pc 7 as the flute states <54>. Finally, surrounding the climactic pc 1 at the end of the large-scale X7(1234), four consecutive instances of 6-18[012578] organize the material: 6-180’ and 6-181 are literal complements and so form the pc aggregate.(18)Such clear aggregate partitions are rare in this piece. Concerning contemporaneous twelve-tone thinking, consult Felix Meyer’s fascinating study of the manuscript and sketches for the Sonatina for Oboe and Harpsichord, an earlier work composed for Marlowe that remained unfinished, in which a twelve-tone row organizes the opening of the first movement (Meyer 2012, 225–27). The series 6-181–6-184–6-185 creates a large-scale projection of an X fragment; that is, the index pcs <145> express X5′(321).(19)The projection of one set by another suggests transpositional combination (Cohn 1988) and Boulezian pitch-class multiplication (Koblyakov 1990; Heinemann 1998; Losada 2014, 2017 & 2019). Of the resulting

Section A2: Isolated Recollections/Predictions and an Example of Local Continuity

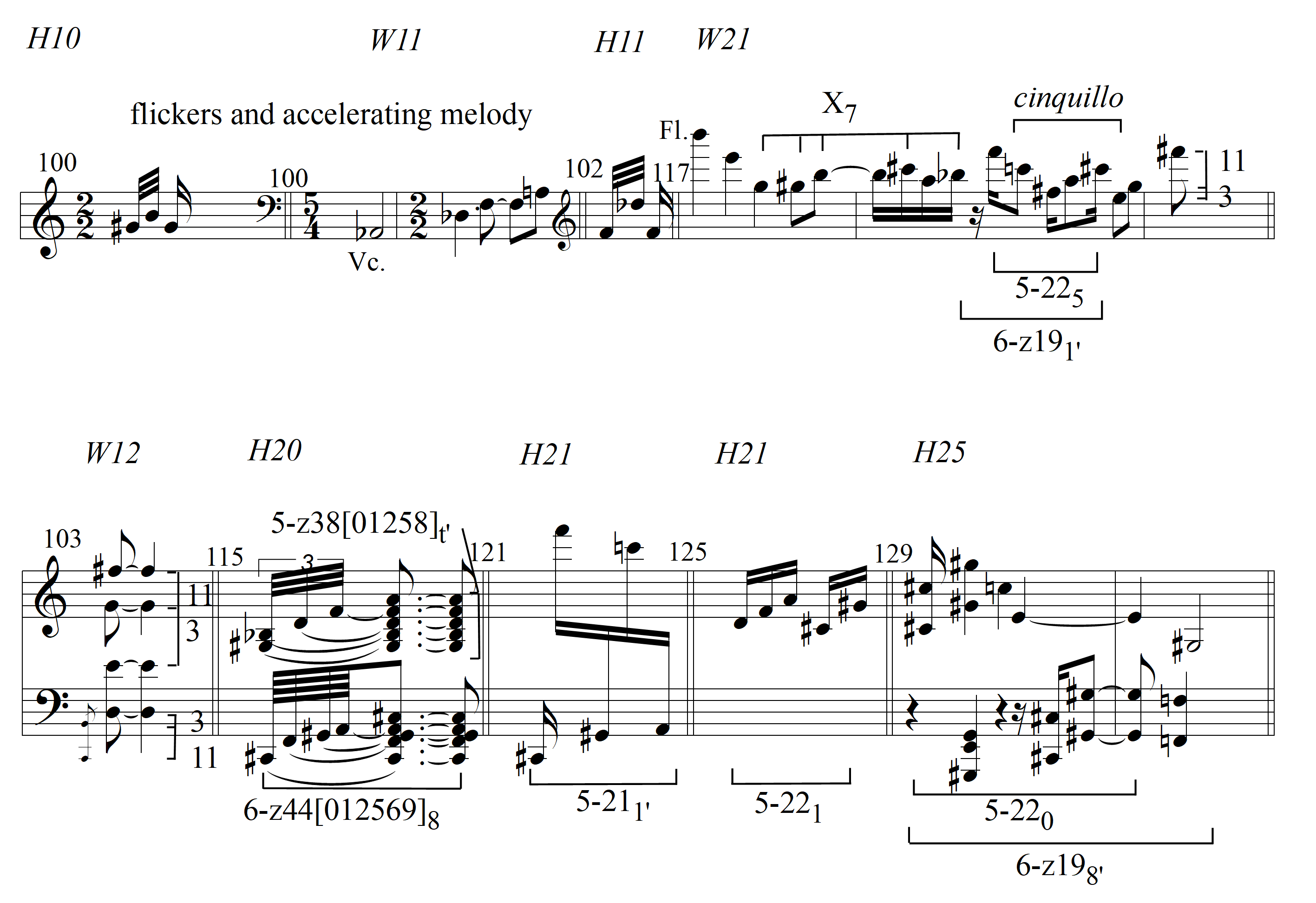

[ 21 ] Having addressed Section A1 in some detail I now provide brief glimpses into Section A2, first highlighting vestiges of the past and hints of the future, and then identifying continuity in the present within a short passage.

Example 10

Excerpts from Section A2.

As indicated on Example 10, thirty-second-note flickers and inversion of the accelerating melody in H10–H11 continue features of the immediately preceding H9. In the flute line of W21 recollections of X7 and <[3] [11]> frame a foreshadowing of Section B’s cinquillo rhythm. The opening chord of W12 has the spacing <[11] [3] [3] [11]>, which recalls <[3] [11]> from W4.(21)The chord here articulates 6-z26[013578], which embeds two instances of 5-20[01568], the set type of the 5-208′ and 5-203 chords that begin nearby W17 and W18, respectively (not shown). H20 is a lone splash, whose gesture looks back to H5–H9 but whose set types, 5-z38 and 6-z44, look forward to Section B. Conversely, H21 recalls earlier splash set types but within a new gestural context; 5-211′ is articulated by a converging compound melody in constant sixteenth notes and then 5-221 by <25918>, an ordered set that is often repeated and fragmented in H22–H24 (which are not shown). The bold imitative lines of H25 trumpet the pc pair {18}, which is a recurring element in most excerpts in this example.

Example 11

W12 - W14.

[ 22 ] Example 11 provides an excerpt from W12–W14 in which all instruments contribute to a continuous sixteenth-note composite rhythm; this provides a marked contrast to H5–H9, during which harpsichord splashes repeatedly interrupt the flute’s efforts to establish sixteenth-note momentum. Set-type repetition provides consistency within subsections, as shown by the pairs of 3-11[037], 5-32[01469] and 6-20[014589] in W12, H12 and W14, respectively. Brief ordered sets connect each subsection to the next; an initial RT0I relation between <063> and <960> gives way to a series of (R)T0 relations involving <38>/<38>, <10>/<01> and <9t3e>/<9t263e>. Further, the oboe features eighth-note descending leaps in both W12 and W13; this gestural similarity, along with temporal proximity and identical starting pitches, makes the latter sound like an intervallically-altered version of the former. Pc 6 plays a unifying role in the passage, acting as a pedal tone throughout H12–W14.

Section A3: Y/Z Reconciliation and Cadence

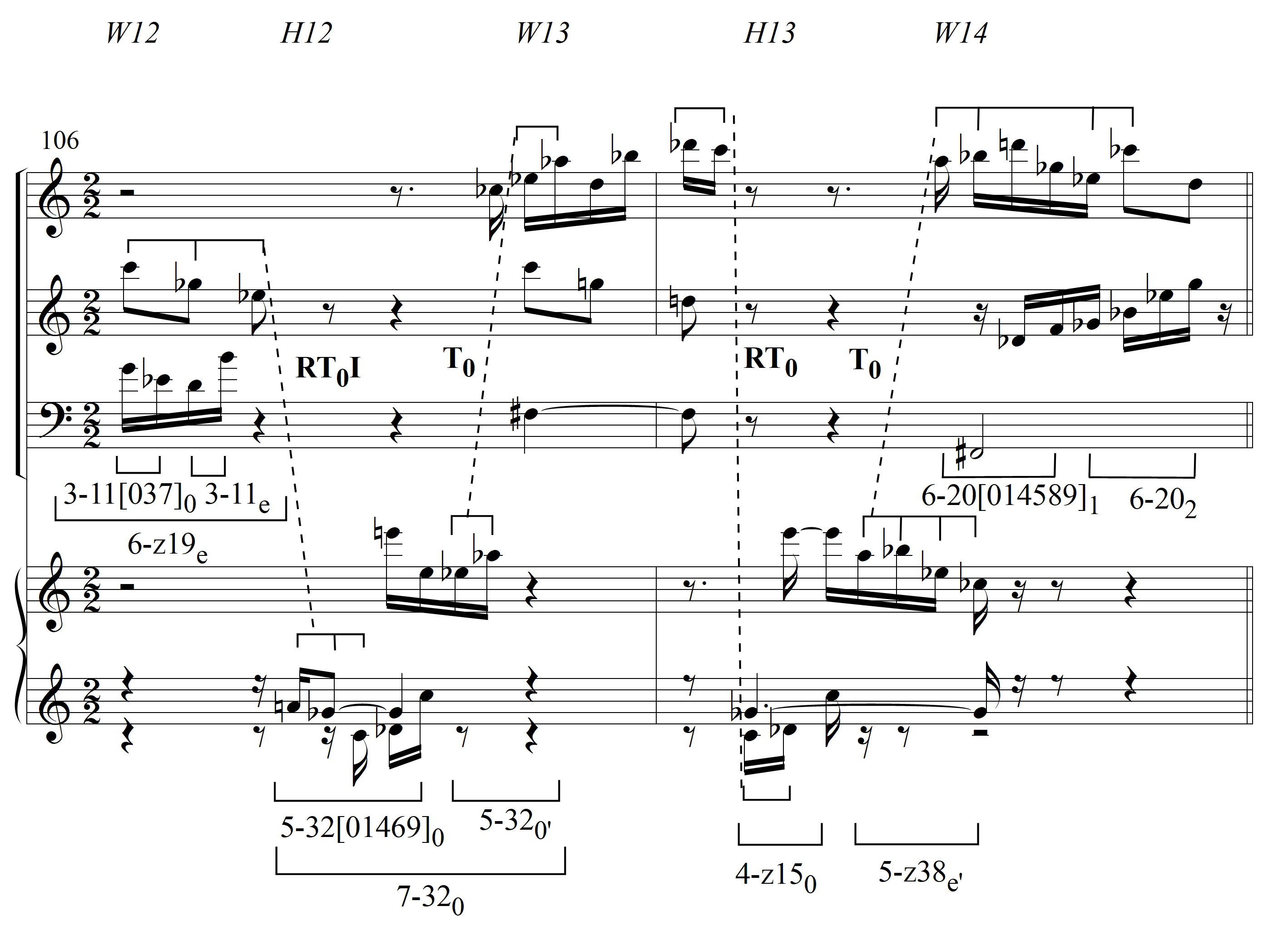

Example 12

Y/Z reconciliation.

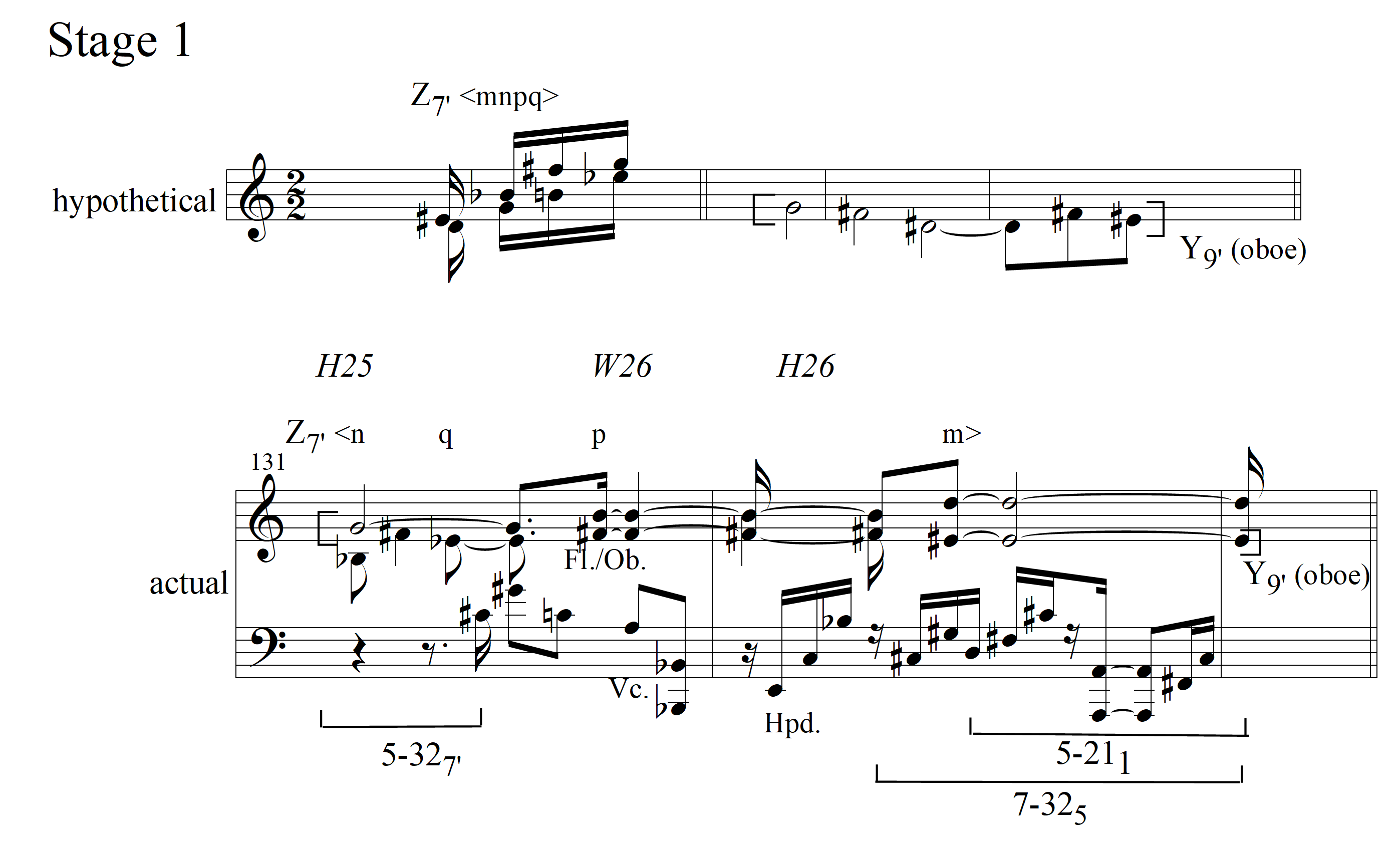

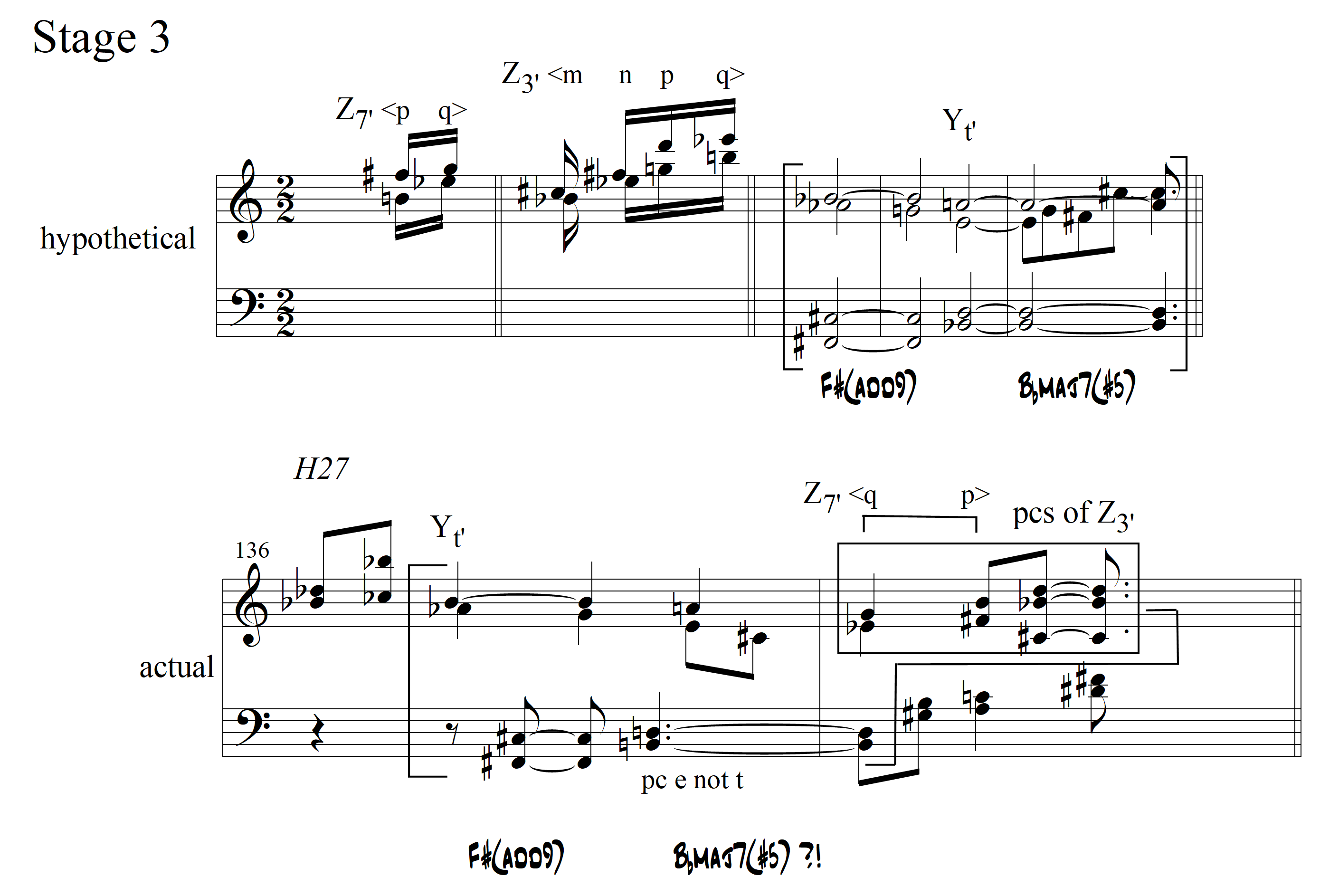

[ 23 ] H25–W31 are dominated by the re-emergence and reconciliation of Y and Z, which takes place in four stages, the first and third of which are dominated by the harpsichord and the second and fourth by winds/cello (see Example 12). The references become ever clearer because the amount of Y that is referenced increases, because the Z dyads eventually become well-defined and well-ordered, and because the later Y/Z pairings highlight Y/Z similarity through shared pitch classes. Each stage refers to both Y and Z via transposed versions of the original Y5′ and Z10′, which appeared first in W4 and W5, respectively. In Stage 1 the harpsichord’s right-hand part recalls most of the oboe line of Y9′ and the dyads of Z7′ in the jumbled order

[ 24 ] Stage 2 recalls the oboe and flute lines of Y5′, at the original pitch-class level but in a sextuplet-sixteenth melodic flourish that contrasts with its original leisurely presentation. As in Stage 1, Z7′ appears here in a jumbled ordering, this time

[ 25 ] In Stage 3 the harpsichord’s Yt′ copies Y5′ completely and in a rhythm that more closely resembles the original, although there are still features that conceal the Yt′/Y5′ relationship: the bass line’s pc e instead of t, the registral position of the final pc 1, and additional pcs. Z7′ appears once again, but in fragmentary form this time, with just two dyads present, <qp>. Z3′ is complete but its dyads are broken apart and jumbled.

[ 26 ] Stage 4 opens with Z5′, whose dyads appear, unadorned and uninterrupted, in ideal retrograde order,

Example 13

Concluding Section A.

[ 27 ] This obstinate flute moment is unceremoniously cut short by the harpsichord’s staccato 6-z11[012457]9′ chord, the only struck six-pc simultaneity of Section A and a particularly dissonant one due to the embedding of the chromatic trichord 3-1.(24)In this movement the chromatic trichord, 3-1[012], tends to be avoided as a simultaneity. Of the movement’s approximately 100 struck three-note simultaneities, not even one articulates 3-1; of the 100 other trichordal simultaneities formed by a combination of held and struck notes, 3-1 appears only twice. Larger simultaneities tend not to embed 3-1. For example, 4-1[0123], the only tetrachordal set type to embed 3-1 twice, is never articulated by a simultaneity, struck or otherwise. When larger simultaneities do embed 3-1, they sometimes seem to do so with the specific intention of creating a dissonant effect. As Persichetti’s comments on intervallic content suggest, the chromatic trichord is the only three-note sonority with one mild dissonance and two sharp dissonances (Persichetti 1961, 20). There is clear evidence that Carter had already begun to think about trichordal embedding within larger sets at this point in his career. Specifically, amongst the sketches for the First String Quartet is a page on which Carter, using a self-devised numbering system, explores the trichordal content of a 6-z24 chord, noting that ten trichord types are present and that 3-1 and 3-8[026] are absent (Soderberg 2012, 244). The subsequent disappearance of pcs 5 and 8 leaves a sustained consonant chord, 4-23[0257]2, a pentatonic subset that maximizes interval class 5 and avoids interval class 1 (see H31 in Example 13). W32’s varied repetition of Y5′ has pc e resolve to pc 0 instead of pc 1, creating Fmaj7 instead of Fmaj7(♯5), a more consonant sonority that links to the sustained cadential Gmaj7 of H4 and the Dmaj7 and Fmaj7 chords of H9. The subsequent recapturing of pcs 5 and 8 initiates a pentatonic cello line in W33. Section A concludes shortly thereafter with W34’s hexatonic answer to W33’s pentatonic cello line. The final six pcs articulate 6-20, the hexatonic collection, whose only septachordal superset, 7-21, and whose only pentachordal subset, 5-21, have played such leading roles in Section A.

Section B: Textural Contrast and Jazz

Example 14

Section B; tutti outburst.

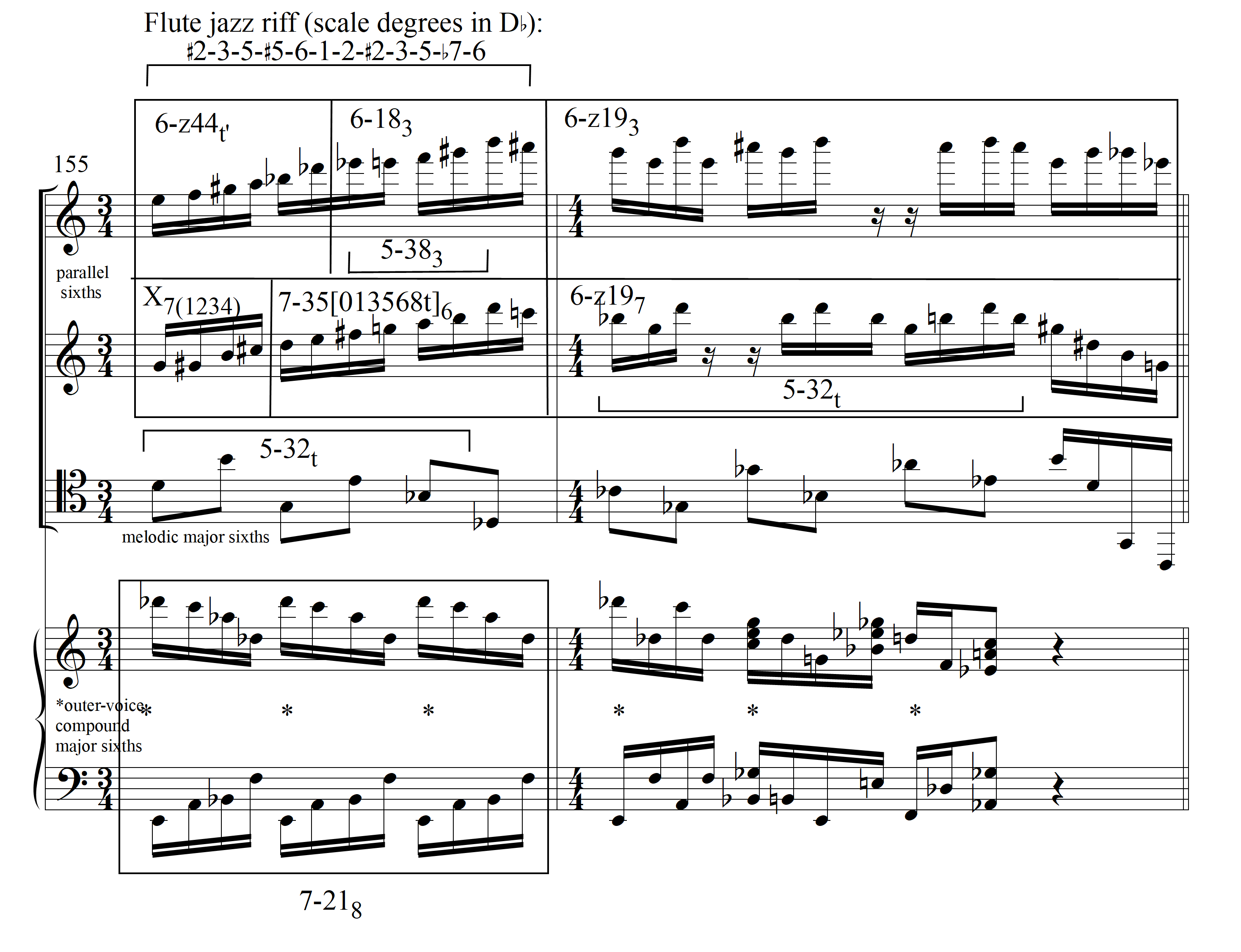

[ 28 ] Section B begins with a tutti outburst of sixteenth-note activity (see Example 14)—a startling contrast to Section A, where the harpsichord and the flute/oboe/cello trio never play simultaneously. Despite this contrast, instrumental parsing of the music reveals several references to Section A. Most clearly, X7(1234) in the oboe line provides a brief T0 recollection of the very opening of the movement and of large-scale structure in the splash section of A1, while the harpsichord’s 7-218 recalls the many recent instances of Z, though without the dyadic parsing that a clearer Z reference would feature. The flute’s 6-z44t′ and 6-183 make specific reference to the isolated splash of A2 and the accompaniment of the accelerating melody at the end of A1, respectively. Creating local continuity are the T4-related 6-z193 and 6-z197 in flute and oboe, the side-by-side 5-32[01469]t involving cello then flute/oboe, and the interval of the sixth (usually major), which arises through parallel motion in the flute/oboe, within the leaping cello line, and in outer voices in the harpsichord where a compound major sixth appears on each beat.

[ 29 ] Several features of the passage also foreshadow the jazzy feel of the upcoming J theme. First, thinking of the first measure of the flute line in terms of the key of D♭ major reveals the scale-degree succession ♯2–3–5–♯5–6–1–2–♯2–3–5–♭7–6, an ultra-clear boogie-woogie/jazz riff, especially if you mentally ‘swing’ the sixteenths. The harpsichord’s repeating arpeggios that emphasize D♭ also reinforce this interpretation.

Example 15

Octatonic chords at the tutti outburst.

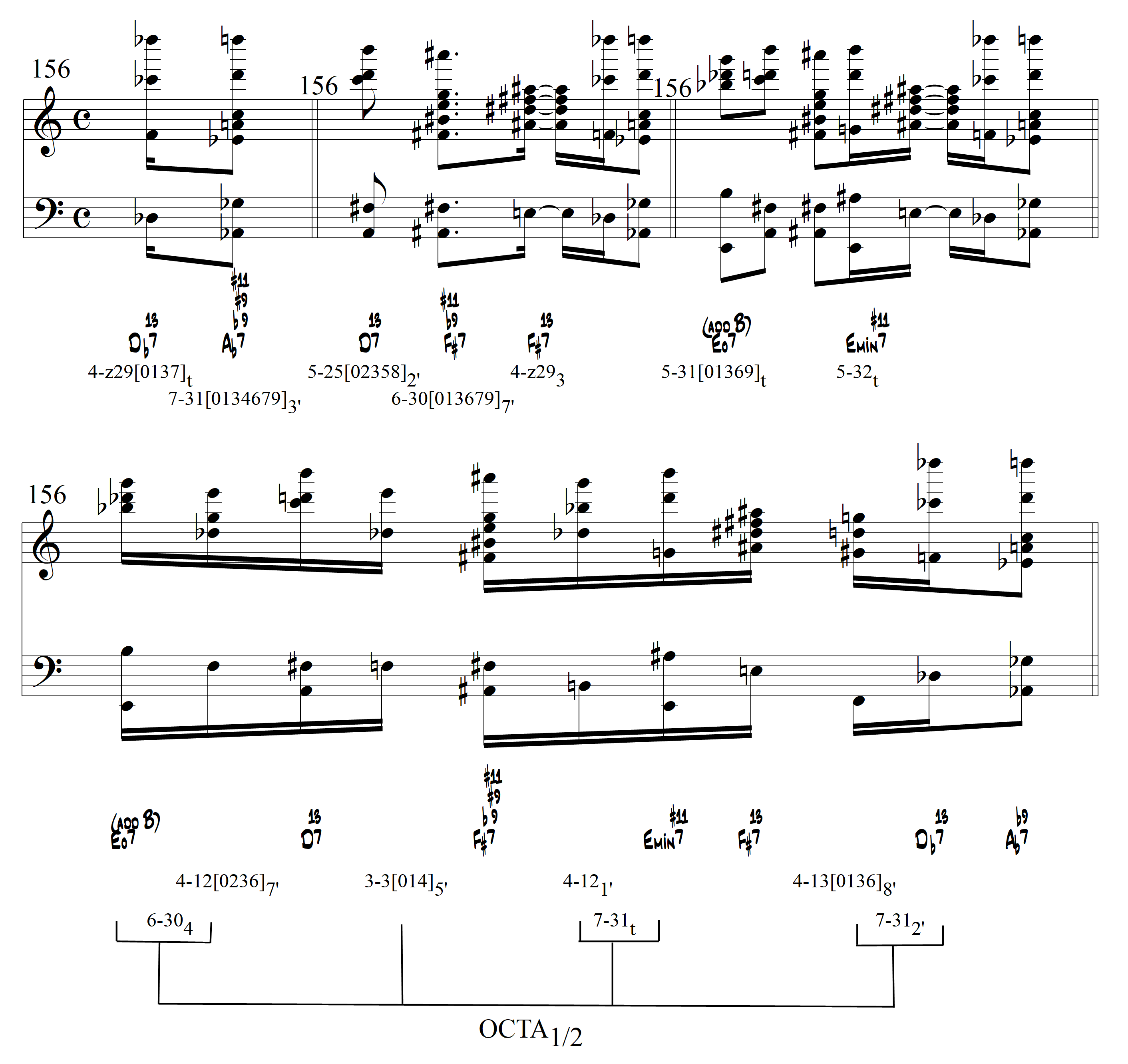

[ 30 ] Second, the harmony in the second measure of the outburst begins to feel jazz-like, especially due to the appearance of dominant sevenths with various octatonic extensions (♭9, ♯9, ♯11, and 13). The clearest of these are D♭7(13) and A♭7(b9, ♯9, ♯11), which conclude the passage. They are in root position and their extensions inhabit the upper register, as shown at the beginning of Example 15, where the entire texture appears on two staves. Preceding these chords are D7(13), F♯7(♭9, #11) and F♯7(13); although not in root position the upper registral placement of chordal extensions supports a tertian interpretation. Two further chords, Edim7 with added B and Emin7(♯11), also articulate octatonic subsets—5-32t and 5-31[01369]t, respectively. Moreover, 5-31 is the abstract complement of 7-31, which is articulated in this measure by 7-313′/Ab7(♭9, ♯9, ♯11). As shown in the second system of Example 15, the remaining four chords in the measure are part of the C♯/D octatonic collection (OCTA1/2) that dominates the passage.

Example 16

J3.

[ 31 ] Example 16 identifies J3 = <5e834> atop three-note chords of various set types. While J3 articulates 5-z38[01258] the lower notes articulate its z-related set type, 5-z18[01457]. Section B includes four further instances of J, each time with this characteristic cinquillo rhythm. The remainder of Section B mixes J with various outburst fragments, pizzicato ‘walking’ cello lines and quick, regular timbral oscillations, either between two fingerings of the same pitch—a technique also employed in his Eight Etudes and a Fantasy for Wind Quartet – or between two manuals of the harpsichord. A representative excerpt, given as Example 17, uses specific set types and more general and imprecise textural/rhythmic relations to reference both the tutti outburst and J3.

Example 17

An excerpt from Section B.

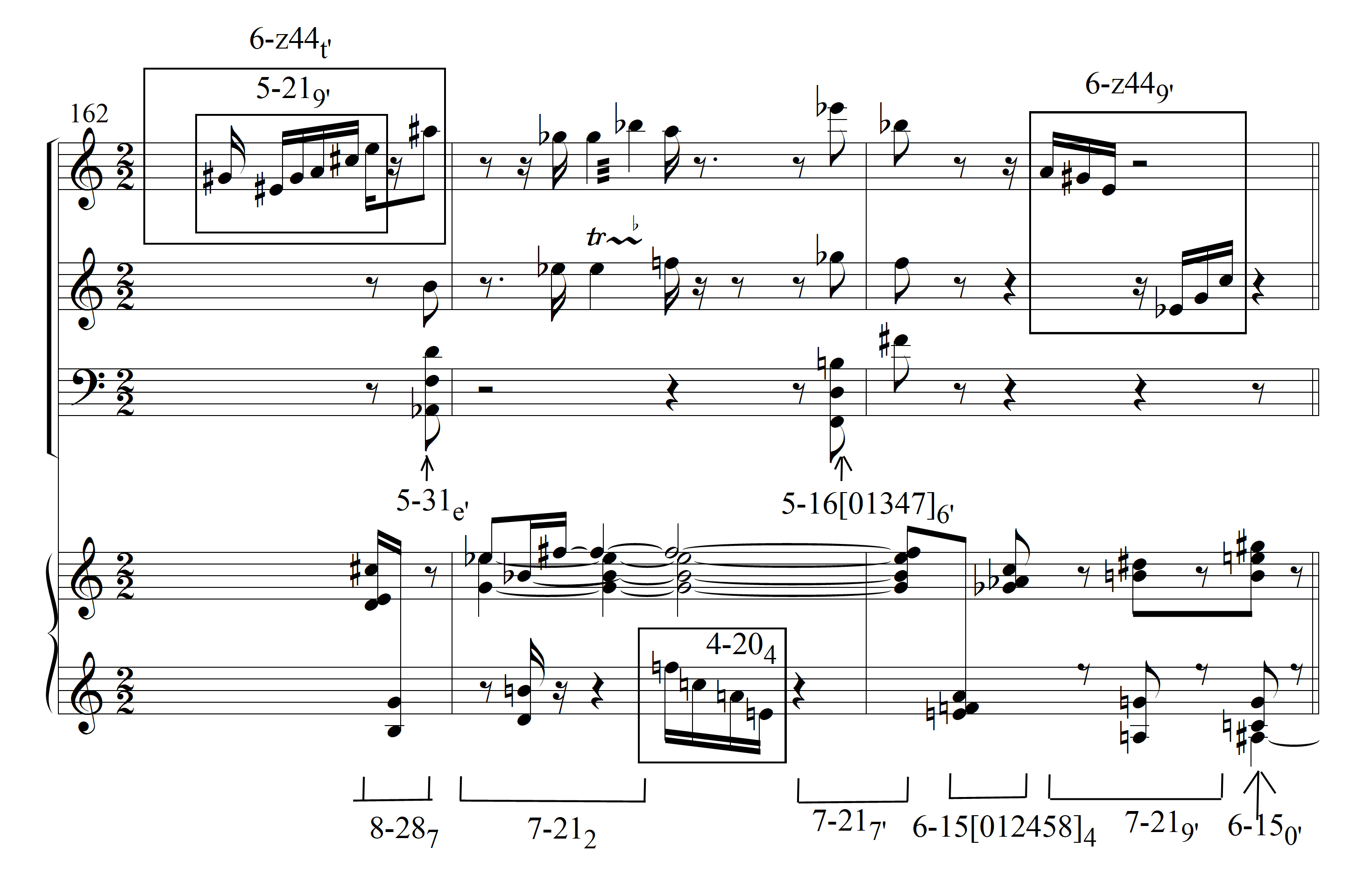

In each instrument but the cello there are sixteenth-note melodic lines that create loose, fragmentary recollections of the sixteenth-note melodic lines from the outburst. These lines articulate set types familiar from the outburst (6-z44) and elsewhere (4-20, 5-21). The first five chords of the harpsichord part vaguely recall the syncopation and chordal texture of J3. In the other instruments, the larger punctuating chords 5-31e′ and 5-16[01347]6′ are octatonic subsets, like those at the outburst. The excerpt continues the movement’s reliance on 7-21 and provides some more local emphasis on one of its subsets, 6-15[012458].

Section B: Textural Contrast and Jazz

Example 18

Excerpts from the Coda.

[ 32 ] As shown in Example 18, the Coda combines various distinctive features of Sections A and B in several ways. Measures 179-183 begin with a splash, which recalls Section A, and articulate J5, which recalls Section B. This splash/J fusion means that Sections A and B are being recalled simultaneously, one by gesture and the other by pc motif. The culminating octachord articulates 8-23[0123578t], complementing the 4-23 from the end of Section A3. Immediately following, there is a leisurely statement of <476> in the registral spacing <[3] [11]>, familiar from Section A’s W4, W5 and W12, but with added timbral oscillation—the trading of pcs 4 and 7 back and forth between flute and cello—which recalls Section B.

[ 33 ] Measures 187-190 combine X7 from Section A and two forms of J from Section B. At measure 187, the harpsichord begins X7 twice, with its right-hand <78> and chordal 4-14[0237]8′ precisely duplicating H2 from Section A1. However, the quintuplet left-hand notes are new; in the first case they create 4-14e, making a local set-type connection to the following 4-148′, and in the second case they create a temporally-jumbled J7′(42315), whose registral spacing, <[5] [3] [3] [2]>, inverts J3’s <[2] [3] [3] [5]>. The X/J combination then continues. First, quintuplet eighths juxtapose jumbled versions of both X7 and J5, highlighting an RT2 connection between their subsets

[ 34 ] In the final excerpt’s whirlwind of sextuplet sixteenths (starting at m. 192), excerpts from the Section B outburst frame a reference to Section A2’s compound-melody texture that embeds two jumbled X references.(25)Shinn identifies Bogenform (arch form), both over the entire movement and within what Shinn calls a second A section (which I call the Coda). Referring to measures 190–194, “…the increased activity at that point has references to the ‘B’ portion of the movement. This brief surge of energy creates within the final ‘A’ section an arch corresponding to that of the entire movement” (Shinn 1975, 56). Shinn’s interpretation of the Coda does not conflict with mine; rather it seems to point out that surface gestures most clearly reference Section B during measures 190–194 and Section A elsewhere. The passage also suggests closure. A fleeting C7–D7–G progression provides a comically brief allusion to a standard cadence in G major. Moreover, in a recollection of a pc fragment originally encountered in W4 of Section A1, there is fundamental emphasis on <47>; that is, the first, highest and lowest notes of the passage articulate pc 4 and the last note pc 7. The conclusion of the movement (not shown) hammers home the <47> motion with repetitions of both pcs in the bass as the compound-melody texture continues and then in a final <47>, where pc 4 is articulated by quick timbral oscillations in the winds akin to those in Section B and pc 7 by harpsichord and winds – separately – in a nod to the texture of Section A in general and the very opening of the movement in particular.

— ◊ —

[ 35 ] The preceding analysis includes “many kinds of musical characters:” ordered series (X, J, <25918>, the accelerating melody, and a boogie-woogie/jazz riff), partially-ordered sets (Y and Z), spatial sets (<[3] [11]>, <[4] [3] [1] [3]>, <[3] [5]>, and <[2] [3] [3] [5]>) and textural-rhythmic features (splash, flicker, string of sixteenth notes, compound melody, and timbral oscillation). Concerning set-type relations, the analysis focuses mainly on set-type repetition, although some associations are based on sub-/super-set relations, complementation, maximal similarity and z-relations.(26)Some of the Sonata’s prominent set types also resonate with the theme of the Variations for Orchestra (1953–55); that is, the first, fourth and eighth phrases of the 74-note theme articulate 5-10 (the set type of X), 5-21 and 7-32, respectively. For a discussion of thematic relationships in the Variations see Nichols (2016).

[ 36 ] The various musical characters develop in diverse ways: Whereas J repeats a few times with its cinquillo rhythm and registral layout intact, X undergoes a rigorous thematic development, saturating a multi-voice texture, organizing the flute line, and being composed out over a longer stretch of time. Complete repetitions of Y that retain the original tempo give the listener time to luxuriate but quick, fragmentary Y references are gone in a flash. Numerous melodic and harmonic expressions of 5-21 unify the movement as a whole whereas a pair of side-by-side instances of 7-z38 neatly explains only a brief excerpt of the Coda. The characters also interact in diverse ways, as when the thematic working out of X generates Y and <[3] [11]>, Y and Z gradually reconcile, and splash and J fuse.

[ 37 ] Within this “web of continually varying cross references” (Carter 1969, 228) there is much to notice initially and ever more to enjoy with repeated hearings and further study. Textural-rhythmic features and straightforward thematic/harmonic relations might dominate earlier experience whereas subtler thematic references and more complex and/or fleeting set-type relations might emerge later in the listening/learning process. Such relational diversity not only draws one into Carter’s world, but also provides thereafter an endless series of opportunities for deepening musical experience and continued growth.

Footnotes

2. Measure numbers in the movement run from 69 to 202.

3. For Sylvia Marlowe, who commissioned this work from Carter, jazz and the harpsichord were a routine pairing; she regularly performed in Baroque, pop, jazz and other styles in recital, on the radio, at the Rainbow Room in Rockefeller Center and on recordings (her debut record was entitled “Bach to Boogie-Woogie”). For more on her significant contribution to the resurgence of the harpsichord in mid-century America see Palmer (1989, esp. 110–117).

4. Carter uses the term “splashing dramatic gesture” to indicate a different figure that begins the first movement (Carter 1969, 231).

5. The use of conventional tertian chord symbols is motivated not only by such statements of Y, but also by cadential moments and the jazz-inspired harmony in Section B.

6. For example, in Zt′ the ‘m’ dyad is {58}, which appears at the beginning; whereas in Z7′ the ‘m’ dyad is {25}, T9 of {58}, which appears at the end.

7. The rhythm can be characterized as a cinquillo (2+1+2+1+2) as in Washburne (1997, 59–60) or as a variant of the tresillo (3+3+2 ≈ (2+1)+(2+1)+2)) as in Rahn (1996, 73).

8. Randall Shinn identifies some of the instances of <[3] [11]> that I point to later in the paper (Shinn 1975, 42). In general, Shinn’s analysis, which addresses all three movements, focuses on interval, theme/motive, texture, and form. I build on his comments about the second movement, adding an account of set-type structure and more detailed discussions of theme.

9. For maximal similarity consult Morris (2001, 79 and Appendix C page 5). Z-relations, complement relations and subset/superset relations have been explained by, among others, Joseph Straus (2016, 112–123).

10. The 7-21/6-20/5-21 relations are particularly interesting. 7-21 has the Complement Union Property (CUP) because the union of any 6-20 and any non-intersecting single note forms an instance of 7-21 (Morris 1990). 5-21 is embedded within 6-20 six times because omitting any note from 6-20 creates 5-21. For more sophisticated applications of CUP in Carter’s music consult Capuzzo (2000) and Roeder (2009).

11. For a discussion of chordal extensions in the diminished scale (a.k.a. the octatonic collection) consult Levine (1995, 78–88, esp. 84).

12. As others have noted, the timbral changes on pitch G4 strongly recall the seventh movement of Eight Etudes and a Fantasy (1950) for Woodwind Quartet (Schiff 1998, 115; Shinn 1975, 39). Randall Shinn views <78e> as globally generative: “The three-note motive, G, G-sharp, B, is extremely important because the intervals involved, particularly the minor third and the minor second, are used in the generation of a great number of motives in the movement” (Shinn 1975, 40).

13. The use of an incomplete sequence of order positions in a parenthesized subscript indicates a subset of an ordered set, as with X3′(1234), which is missing the fifth note of X3′. This practice follows Sallmen 2007’s analysis of “In Genesis” from In Sleep, In Thunder (1981). Note that the main theme articulates 5-10[01346] in both works, <78e1t> in the Sonata and <689635> in “In Genesis”.

14. Some fragments have multiple possible labels; for example, Xt′(451) = X4(154) and X7′(512) = Xt′(453).

15. This recalls the behavior of the dolce stream within Riconoscenza per Goffredo Petrassi, “…after each interruption by another stream, it recommences by repeating the last few pitches of its previous appearance” (Roeder 2012, 124).

16. The expression of X7(1234) locally and then over the course of a few phrases engages the notions of motivic enlargement (Alegant and McLean 2001) and composing out (Straus 2004 and 2016, 159–63). The all-interval tetrachord 4-z15 appears often melodically and only occasionally harmonically in the Sonata, a seeming reversal of its use in Carter’s previous work: “My First String Quartet is based on an ‘all-interval’ four-note chord, which is used constantly, both vertically and occasionally as a motive…” (Edwards 1971, 106–107). For further discussion of the role of 4-z15 in the First Quartet see, for example, Bernard (1993) and Rao (2014). 4-z15 is also featured in the “Recitative” and “Canaries” movements of the Eight Pieces for Four Timpani (1950) (Schiff 1998, 133–34). To see the other all-interval tetrachord, 4-z29[0137], in a thematic context consult the analysis of Esprit rude/Esprit doux (1985) by John Roeder (2012, 115–122). 4-z15 and 4-z29 are used in competitive opposition in Scrivo In Vento (Mailman 2009).

17. Speaking about the First Quartet, Schiff characterizes the second violin’s entrance as “mistaken” because the instrument then drops out, waits and begins again (Schiff 1998, 57).

18. Such clear aggregate partitions are rare in this piece. Concerning contemporaneous twelve-tone thinking, consult Felix Meyer’s fascinating study of the manuscript and sketches for the Sonatina for Oboe and Harpsichord, an earlier work composed for Marlowe that remained unfinished, in which a twelve-tone row organizes the opening of the first movement (Meyer 2012, 225–27).

19. The projection of one set by another suggests transpositional combination (Cohn 1988) and Boulezian pitch-class multiplication (Koblyakov 1990; Heinemann 1998; Losada 2014, 2017 & 2019).

20. Such accelerations are identified as a characteristic feature of Carter’s style by David Schiff (Schiff 1998, 34).

21. The chord here articulates 6-z26[013578], which embeds two instances of 5-20[01568], the set type of the 5-208′ and 5-203 chords that begin nearby W17 and W18, respectively (not shown).

22. In the material between Stages 3 and 4 (not shown), the cello states the q and p dyads of Z5’ as double stops in a seeming argument with the harpsichord’s surrounding perfect-fifth based sixteenths and a six-pc chord discussed in the next paragraph.

23. For another story of reconciliation consult Roeder’s analysis of Riconoscenza per Goffredo Petrassi (Roeder 2012, 122–28).

24. In this movement the chromatic trichord, 3-1[012], tends to be avoided as a simultaneity. Of the movement’s approximately 100 struck three-note simultaneities, not even one articulates 3-1; of the 100 other trichordal simultaneities formed by a combination of held and struck notes, 3-1 appears only twice. Larger simultaneities tend not to embed 3-1. For example, 4-1[0123], the only tetrachordal set type to embed 3-1 twice, is never articulated by a simultaneity, struck or otherwise. When larger simultaneities do embed 3-1, they sometimes seem to do so with the specific intention of creating a dissonant effect. As Persichetti’s comments on intervallic content suggest, the chromatic trichord is the only three-note sonority with one mild dissonance and two sharp dissonances (Persichetti 1961, 20). There is clear evidence that Carter had already begun to think about trichordal embedding within larger sets at this point in his career. Specifically, amongst the sketches for the First String Quartet is a page on which Carter, using a self-devised numbering system, explores the trichordal content of a 6-z24 chord, noting that ten trichord types are present and that 3-1 and 3-8[026] are absent (Soderberg 2012, 244).

25. Shinn identifies Bogenform (arch form), both over the entire movement and within what Shinn calls a second A section (which I call the Coda). Referring to measures 190–194, “…the increased activity at that point has references to the ‘B’ portion of the movement. This brief surge of energy creates within the final ‘A’ section an arch corresponding to that of the entire movement” (Shinn 1975, 56). Shinn’s interpretation of the Coda does not conflict with mine; rather it seems to point out that surface gestures most clearly reference Section B during measures 190–194 and Section A elsewhere.

26. Some of the Sonata’s prominent set types also resonate with the theme of the Variations for Orchestra (1953–55); that is, the first, fourth and eighth phrases of the 74-note theme articulate 5-10 (the set type of X), 5-21 and 7-32, respectively. For a discussion of thematic relationships in the Variations see Nichols (2016).

Works Cited

Alegant, Brian and Donald McLean. 2001. “On the Nature of Enlargement.” Journal of Music Theory 45, no. 1:31-72.

Bernard, Jonathan W. 1983. “Spatial Sets in Recent Music of Elliott Carter.” Music Analysis 2, no. 1: 5-34.

________. 1988. “The Evolution of Elliott Carter’s Rhythmic Practice.” Perspectives of New Music 26, no. 2: 164-203.

________. 1993. “Problems of Pitch Structure in Elliott Carter's First and Second String Quartets.” Journal of Music Theory 37, no. 2: 231-66.

Capuzzo, Guy. 2000. “Variety Within Unity: Expressive Ends and Their Technical Means in the Music of Elliott Carter, 1983−1994.” Ph.D. diss., University of Rochester.

Carter, Elliott. 1952. Sonata for Flute, Oboe, Cello and Harpsichord. Associated Music Publishers.

________. 1969. Liner notes for Nonesuch recording H-71234 Two Sonatas, 1948 and 1952. Reprinted in Elliott Carter, Collected Essays and Lectures, 1937-1995. Ed. Jonathan W. Bernard. Rochester, NY: Rochester University Press (1997): 228-231.

Cohn, Richard L. 1988. “Inversional Symmetry and Transpositional Combination in Bartók.” Music Theory Spectrum 10: 23-38.

Edwards, Allen. 1971. Flawed Words and Stubborn Sounds: A Conversation with Elliott Carter. New York: W.W. Norton.

Koblyakov, Lev. 1990. Pierre Boulez: A World of Harmony. Chur: Harwood Academic Publishers.

Heinemann, Stephen. 1998. “Pitch-Class Set Multiplication in Theory and Practice.” Music Theory Spectrum 20, no. 1:72-96.

Levine, Mark. 1995. The Jazz Theory Book. Petaluma: Sher Music.

Link, John. 2019. “Harmony in Elliott Carter’s Late Music.” Music Theory Online 25, no. 1.

Losada, Catherine. 2014. “Complex Multiplication, Structure and Process: Harmony and Form in Boulez's Structures II.” Music Theory Spectrum, 36, no. 1: 86-120.

________. 2017. “Between Freedom and Control: Composing Out, Compositional Process, and Structure in the Music of Boulez.” Journal of Music Theory 61, no. 2: 201-242.

________. 2019. “Middleground Structure in the Cadenza to Boulez’s Éclat.” Music Theory Online 25, no. 1.

Mailman, Joshua B. 2009. “An Imagined Drama of Competitive Opposition in Carter’s Scrivo in Vento, with Notes on Narrative, Symmetry, Quantitative Flux, and Heraclitus.” Music Analysis 28, nos. 2-3: 373-422.

Meyer, Felix. 2012. “Left by the Wayside: Elliott Carter’s Unfinished Sonatina for Oboe and Harpsichord.” In Elliott Carter Studies. Ed. Marguerite Boland and John Link. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 217-235.

Morris, Robert D. 1990. “Pitch-Class Complementation and its Generalizations.” Journal of Music Theory 34, no. 2: 175-246.

________. 2001. Class Notes for Advanced Atonal Music Theory. Lebanon, NH: Frog Peak Music.

Mullis, Chris. 2018. “Elliott Carter interviewed by Chris Mullis (December 8, 1998).” Elliott Carter Studies Online 2 [27].

Nichols, Jeff. 2016. “Mistaken Identities in Carter’s Variations for Orchestra.” Elliott Carter Studies Online 1.

Palmer, Larry. 1989. Harpsichord in America: A Twentieth-Century Revival. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Persichetti, Vincent. 1961. Twentieth-Century Harmony: Creative Aspects and Practice. New York: Norton.

Rahn, Jay. 1996. “Turning the Analysis Around: Africa-derived Rhythms and Europe-derived Music Theory.” Black Music Research Journal 16, no. 1: 71-89.

Rao, Nancy. 2014. “Allegro scorrevole in Carter’s First String Quartet: Crawford and the Ultramodern Inheritance.” Music Theory Spectrum 36, no. 2: 181-202.

Roeder, John. 2009. “A Transformational Space for Elliott Carter’s Recent Complement-Union Music.” In Mathematics and Computation in Music: First International Conference, MCM 2007. Ed. Timour Klouche and Thomas Noll. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag, 303-310.

________. 2012. “‘The matter of human cooperation’ in Carter’s Mature Style.” In Elliott Carter Studies. Ed. Marguerite Boland and John Link. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 110-137.

Sallmen, Mark. 2007. “Listening to the Music Itself: Breaking Through the Shell of Elliott Carter’s ‘In Genesis.’” Music Theory Online 13, no. 3.

Schiff, David. 1998. The Music of Elliott Carter. 2nd edn. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Shinn, Randall. 1975. “An Analysis of Elliott Carter’s Sonata for Flute, Oboe, Cello, and Harpsichord (1952); ‘Chamber Concerto’ for Percussion Solo and Ten Winds.” DMA Thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Soderberg, Stephen. 2012. “At the Edge of Creation: Elliott Carter’s Sketches in the Library of Congress.” In Elliott Carter Studies. Ed. Marguerite Boland and John Link. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 236-249.

Straus, Joseph N. 2004. “Atonal Composing Out.” Order and Disorder: Music-Theoretical Strategies in 20th-Century Music. Leuven: Leuven University Press. 31-51.

________. 2016. Introduction to Post-Tonal Theory. 4th edn. New York: W. W. Norton.

Washburne, Christopher. 1997. “The Clave of Jazz: A Caribbean Contribution to the Rhythmic Foundation of an African-American Music.” Black Music Research Journal 17, no. 1: 59-80.