Balancing the Familiar and the Unfamiliar: Three Elliott Carter Pieces with Quiet Endings

Guy Capuzzo

Abstract

Elliott Carter’s penchant for ending many of his compositions with a loud attack followed by a quiet passage or section is well known. While we sometimes know why Carter ended a given piece in this way (through interviews and program notes), relatively little attention has been paid to how he ended these pieces. I submit that the musical character of a given quiet ending derives in part from the balance (or imbalance) of familiar and unfamiliar elements. Analytic vignettes from Mnemosyné (2011), Changes (1983) and “Somewhere” from A Sunbeam’s Architecture (2010) explore the compositional strategies and variety of musical expression present in these three quiet endings.

“In my music it is always the still small voice that wins out.”

—Elliott Carter, 1969

“[U]ndramatic, ‘anti-heroic’ endings are

virtually a defining feature of Carter’s late music.”

—Felix Meyer and Anne C. Shreffler, 2008

“[A]n unusual number of (Carter’s) later works end with an emphatic, typically very loud, climax after which the music reverberates and undergoes sonic decay.”

—Richard Wilson, 2008(1)Stone (1969, 572), Meyer and Shreffler (2008, 294), Wilson (2008, 76).

Introduction

[ 1 ] Time and time again, scholars and musicians have commented on how often Carter’s compositions end with a loud attack followed by a quiet passage or section. The quiet endings vary greatly in length and musical character, alternately creating suspense, surprise, humor, or a sense of playfulness; prompting recollection; stabilizing, destabilizing, or “providing commentary on” the earlier music; and bringing structural processes to their conclusions. I submit that the expressive character of a given quiet ending derives in part from the relative emphasis on familiar and unfamiliar elements. As an illustration, Example 1 presents excerpts from Mnemosyné (2011), a brief violin solo composed in memory of Helen Carter.(2)To the best of my knowledge, there are no published analytic studies of Mnemosyné. On August 28, 2017, Boosey & Hawkes issued a revision notice indicating that the third note in m. 7 should be F4, not G4.

Example 1

Elliott Carter, Mnemosyné, excerpts

© Copyright 2011 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes company.

International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by permission.

[ 2 ] Let us begin with some observations about musical characters in the work. Measures 1−5 juxtapose the piece’s two primary characters, one legato and one staccato. The legato character opens the piece, marked dolce, mf, espressivo. After a brief silence, the staccato character enters with a two-note gesture, marked p, leggiero. As indicated by circles on the example, the staccato gesture’s pitches and unordered pitch interval are taken from the legato statement. The alternation of legato and staccato characters separated by rests will carry through the entire piece.

[ 3 ] The second legato entry (mm. 6−12) borrows four pitches and all but one of its unordered pitch intervals from the first legato entry, as shown on the example. There is a close relation involving contour as well: the −, +, −, +, +, − contour that begins the second legato entry inverts the previous +, −, +, −, −, + (+ = ascent; − = descent). The second legato entry also recalls the first staccato entry, duplicating the latter’s unordered pitch interval 2 and one of its pitches (A♭/G♯4). The second staccato entry (mm. 12−13) likewise repeats elements previously stated by both characters. From the first staccato entry, it duplicates unordered pitch interval 2 and the pitch G♭/F♯4. From the second legato entry, it retains three pitches, all but one of its unordered pitch intervals, and the −, +, −, +, +, − contour.

[ 4 ] The third legato entry (not shown) continues the gradual lengthening (in number of beats) and registral expansion that distinguished legato entry 2 from legato entry 1. By contrast, the third staccato entry (mm. 36−37) consists solely of a two-note ascending gesture; the number of pitches and upward direction recalls the first staccato entry. However, the volume and attack of the third staccato entry is somewhat out of character: it is forte and accented, not soft, staccato, and leggiero. This serves to continue the forte dynamic level first reached in the music following the third legato entry and returned to in each subsequent legato entry. The remaining staccato entries go on to reestablish the quiet, light style of the opening two.(3)Given the absence of staccato markings, the presence of accents, and the loud dynamic levels, it is reasonable to ask if staccato entry 3 is not a staccato entry at all, but instead part of the legato music. Readers with access to the score of Mnemosyné can quickly confirm that these measures (and the silence before and after them) continue the pattern of alternating legato and staccato characters maintained throughout the piece.

[ 5 ] The piece ends decisively with the legato character’s widest leap and loudest dynamic (both of the entire piece), and the silence that follows confirms the finality of the gesture. But the staccato character has the last word. It begins by restating the pitches of staccato entry 6 in order, as well as B♭/A♯4 from staccato entry 4. The final staccato entry also completes several processes set in motion by earlier staccato entries. One involves a contraction of the lengths of the rests separating attacks within entries: 3 beats (entry 4), 2 ⅓ then 2 beats (entry 5), ⅓ beat (entry 6), and 0 beats (final entry). A second process involves an expansion of the size of leaps: 3 semitones (entry 4), 3 then 7 semitones (entry 5), 10 semitones (entry 6), and 10 then 15 semitones (final entry, F♯5 to E♭4). The third process involves a softening in dynamics within entries: f to poco mf (entry 3), mf to mp (entry 4), mp to p (entry 5), p to p decr. (entry 6 then 7). And in a subtle long-range connection to the opening legato entries, the closing staccato entry restates the +, −, +, − contour from the start of legato entry 1 and the +, +, + contour from the end of legato entry 2.

[ 6 ] However, the expressive character of the quiet ending relies on new factors as well. Chief among these is the final staccato entry’s number of notes, ten, yielding greater density within the entry. Previously, the maximum number of consecutive staccato attacks uninterrupted by rests was three (entry 2). A second factor involves surprise and is perhaps strongest during one’s first hearing of the piece. When one retrospectively associates the string of ten staccato notes with the much shorter one-, two-, and three-note strings played earlier, a degree of surprise may result from the deviation from established norms.(4)Of course, many other factors bear on one’s experience of the quiet ending, perhaps beginning with one’s familiarity with Carter’s music more generally. Finally, while the ending’s leggiero/staccato single note attacks, tapering dynamic level, and closing ascent may create the illusion of fading away to nothing, the aforementioned string of uninterrupted notes and absence of a subsequent legato entry may create the impression of opening a new line of thought at the moment when one would least expect it.(5)I am grateful to an anonymous reader for this insight.

[ 7 ] I have only scratched the surface of how the legato and staccato characters interact in Mnemosyné, and it is not my purpose here to explore that topic with the detail it deserves.(6)A more detailed account of the two characters in Mnemosyné might discuss a) the prominent role of cross-cutting (Schiff 1998, 39) in mm. 34−53 and b) the numerous set-class relations among legato entries 1−2 and the final staccato entry. These relations involve the all-interval tetrachords [0146] and [0137], the all-trichord hexachord [012478], and the eight-note collection [0124678T]. Throughout this paper, square brackets [ ] indicate set classes, angle brackets < > indicate ordered sets, and curly brackets { } indicate unordered sets. Rather, I am interested in the delicate, quiet ending of the piece. Sometimes we know why Carter ended a piece in this manner, as in the case of the Piano Concerto (1965), whose closing piano solo he allegorized as follows: “The piano doesn’t beat the orchestra down. It is victorious by being an individual – if there is a victory” (Schiff 1998, 261). Similarly, in the case of Allegro Scorrevole (1996), the quiet ending reflects the piece’s “bubble” motto as well as Carter’s goal of “end[ing] the symphony on a high piccolo note, which seems to me more fitting for our time than a military peroration” (Meyer and Shreffler 2008, 296). But comparatively little attention has been paid to how Carter ends pieces in this way – how he makes the quiet endings compelling, inevitable, charming, and satisfying, and how the endings balance (or do not balance) familiar elements with new ones.(7)Wilson (2008) discusses the beginnings and endings of several Carter pieces. Link (2012, 51) and Schiff (1998, 90) discuss the ending of Carter’s String Quartet No. 4. On codas by other post-tonal composers, see Casken (2001) on Lutosławski and McLean (2009) on Schoenberg.

[ 8 ] In this paper, I offer readings of Changes for guitar solo (1983) and “Somewhere” from A Sunbeam’s Architecture for tenor and chamber orchestra (2010; poems by E.E. Cummings) with a focus on their quiet endings. I chose the pieces for their contrasting endings: that of Changes is relatively long (19 of the piece’s 150 measures) and involves the conclusion of a long-range polyrhythm, whereas that of “Somewhere” is relatively short (3 of 82 measures) and does not involve a long-range polyrhythm.(8)Mead (2012; 2016) and Link (1994) study the relation between polyrhythm pulses and the musical surface in several Carter compositions. The contrast between a solo instrumental work and a work for voice and orchestra also influenced the selections. In the analysis of Changes, I posit that the coda culminates a piece-wide trend toward quiet isolated pulses of the polyrhythm that articulate quiet isolated presentations of the all-trichord hexachord (ATH) in a texture that Carter (1983), David Schiff (1998, 136−38), and Allan Kozinn (1984, 1−4) refer to as “ringing changes.” In the analysis of “Somewhere,” I argue that the quiet ending “closes” the song’s pitch and dynamic ranges in a depiction of the poem’s central motif of opening and closing.

Changes

[ 9 ] Carter described Changes – the first in a series of brief post-1980 instrumental works – as “music of mercurial contrasts of character and mood, unified by its harmonic and rhythmic structure. Various aspects of the basic harmony are brought out in the course of the work, somewhat like the patterns used by bell-ringers in ringing changes” (Carter 1983). As the piece has been analyzed extensively, the technical aspects of Carter’s description are well known, so I will provide only a brief summary of them here.(9)General sources on Changes include Schiff (1998, 136−38) and Kozinn (1984, 1−4). Discussions of the piece’s pitch language include Link (2002, 10−14) and Capuzzo (2000; 2004; 2007). Discussions of the piece’s long-range polyrhythm include Link (1994, 111−13), Link (n.d.), and Poudrier (2008, 74−91 and 117−23).

[ 10 ] The “mercurial contrasts of character and mood” owe largely to the wide variety of playing styles, including clipped and strummed chords, rapid and/or staccato single-note passages, high-register harmonics, a two-voice contrapuntal texture that David Starobin, the piece’s dedicatee, calls “little duets” (Kozinn 1984, 4), and the ringing changes texture. I define this texture as one in which each pitch class appears in one register only, without octave duplications; pitches repeat in changing orders; and the ATH appears on the musical surface as combinations of smaller held chords overlap with one another, like chords held by the damper pedal on a piano.

[ 11 ] The “basic harmony” to which Carter refers is the ATH. To provide contrast, Carter also employs four hexachords—[012345], [023457], [013458], [024579]—that play roles in two other works of that era, Night Fantasies (1980) and In Sleep, In Thunder (1981) (Schiff 1998, 137). Of these, [013458], figures most prominently in Changes (Schiff 1988, 4). Each of these four hexachords contains members of every interval class except interval class 6, the tritone. In contrast, the ATH contains members of all six interval classes. Accordingly, Schiff observes that “the harmony of Changes therefore contrasts chords by the presence or absence of the tritone” (Schiff 1988, 4).(10)In the preceding sentences, and throughout this paper, “member” is used as a synonym for “pitch-class set.” I shall refer to these four hexachords as the “tritone-free hexachords.”

[ 12 ] Transposition by tritone (henceforth T6) also plays an important role in the piece. Transposing an ATH member by T6 holds four pitch classes invariant; those pitch classes form a pair of tritones that belong to set class [0167]. Transposing any tritone-free hexachord member by T6 will complete the pitch-class aggregate.(11)This is a result of the well-known hexachord theorem, first proven in Lewin (1960). Such aggregates have the potential to be realized spatially as all-interval series, a row type that figures in many Carter works but not Changes, due to the registral constraints imposed by the guitar (Capuzzo 2007). However, Carter alludes to all-interval series in several passages in Changes, which I shall discuss in due course.

[ 13 ] The basis for the work’s rhythmic structure is a 75:56 long-range polyrhythm. On the musical examples, I indicate pulses by two numbers separated by a slash. For instance, 1/75 indicates the first pulse of the stream that contains 75 pulses, and 1/56 indicates the first pulse of the stream that contains 56 pulses. Naturally, the number of notated beats between pulses depends on the notated tempo, which is indicated on each example.

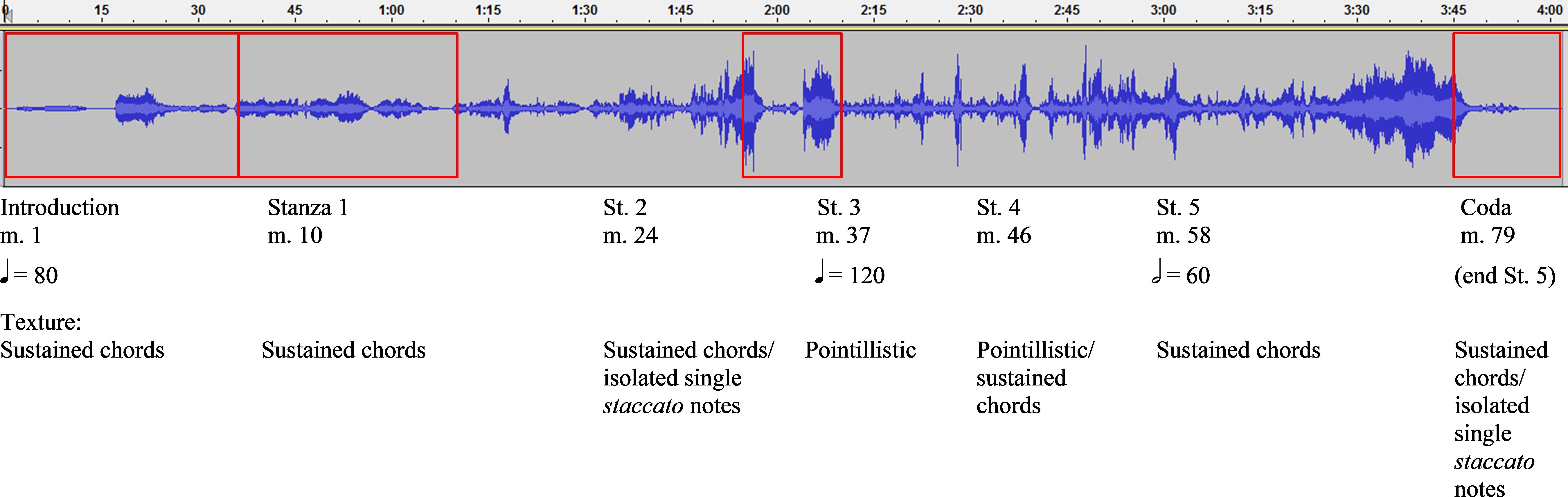

[ 14 ] Let us turn to the form of the piece. Example 2 provides a waveform graph of Changes along with tempo and performance markings, based on a recording by Starobin (Carter 1994). The excerpts I shall discuss are boxed in red.

Example 2

Elliott Carter, Changes, waveform graph

Red boxes indicate excerpts discussed in subsequent examples

[ 15 ] Schiff (1988, 4) describes the form of Changes as “a compressed version of Night Fantasies…a series of short, elided episodes.”(12)Poudrier (2008, 55) and Capuzzo (2000, 43−44) offer accounts of the piece’s form that complement that of Schiff. Taking a broad view, the waveform graph reveals several large sections: the episodes cited by Schiff (mm. 1−88); a scherzando (mm. 89−109); a loud climactic section (mm. 110−114); a passage that releases the tension created by the climactic section (mm. 115−30); and a quiet coda, lento tranquillo (mm. 131−50).

[ 16 ] As stated earlier, the coda marks the culmination of a trend toward quiet isolated pulses of the long-range polyrhythm that articulate quiet isolated statements of the ATH in the ringing changes texture. Kozinn cites m. 51 as the first appearance of this texture (1984, 2). As a point of departure, Example 3 reproduces mm. 51−65.

Example 3

Elliott Carter, Changes, mm. 51−65, polyrhythm pulses

ATHs in solid boxes;

Tritone-free hexachords in dashed boxes

© Copyright 1983 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes company.

International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by permission.

[ 17 ] Let us begin by examining Carter’s use of the ATH in the passage. At ①, two sustained trichords form an ATH, labeled X. At ②, Carter restates the second trichord and follows it with a third. The union of the second and third trichords forms T6 of X, labeled X6.(13)A discussion of this passage, along with Carter’s sketch for it, appears in Capuzzo (2004, 9−10). X and X6 also appear in the rapid strummed lead-up to ① and ②. Later appearances of X and X6, indicated by the numbers ③ through ⑧, use the same pitches as those at ① and ②, and all eight ATHs appear in the ringing changes texture.(14)The recurring realizations of the ATH as the union of two trichords might suggest that Carter is taking full advantage of the all-trichord property, but in fact only seven of the ten possible trichord unions are present. See Link (2002,14) and Carter (2002, 241).

[ 18 ] Example 3 uses dashed boxes to indicate appearances of [024579] and [013458], two of the tritone-free hexachords. Over the course of the work, occurrences of these hexachords will decrease in number, yielding to a near-exclusive use of the ATH in the coda. The playing style helps to distinguish one hexachord type from another: after the rapid strummed lead-up (m. 51), ATHs appear in the ringing changes texture, while the [013458] hexachords occur as rapid single notes (mm. 54, 57) or held single notes marked espressivo (mm. 53−54, 58−60).

[ 19 ] Let us turn to the interaction of the ATH with the long-range polyrhythm. At the notated tempo of ♩ = ca. 100, the pulses of the 75 stream occur every 42 quintuplet sixteenth notes, while the pulses of the 56 stream occur every 45 sixteenth notes (Poudrier 2008, 49, 59, Link n.d.).(15)The tempo, specifically, is 100.5, so that the closing tempo of ♩ = 67 is precisely two-thirds as fast. The initial ATHs (numbered ①−④ on the score) are mostly at the f dynamic level and do not align with polyrhythm pulses, while the later ATHs (numbered ⑤−⑧) eventually drop to p and pp dynamic levels and, with the exception of ATH ⑧, do align with the pulses.(16)More precisely, “ATH x aligns with a pulse” means that one of the attacks in a given ATH formation coincides with a pulse. The soft dynamics and alignment with pulses foreshadow the coda. To understand the final stages of how Carter prepares the coda, Example 4 analyzes the music immediately preceding it.(17)Three features of Example 4 merit discussion. First, pulse 58/75 is not attacked. Second, in a departure from the fixed pitches that characterize the ringing changes texture, pitch-class 6 appears in two registers during mm. 116−22, as G♭4 (m. 116) and F♯2 (m. 119−22) (the guitar sounds one octave lower than written). Likewise, pitch-class 5 appears as F3 (mm. 116−17) and F4 (mm. 121−22). Finally, parentheses in mm. 128−29 indicate that B3 is not part of the [013458].

Example 4

Elliott Carter, Changes, mm. 116−130; ATHs in solid boxes;

Tritone-free hexachords in dashed boxes

© Copyright 1983 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes company.

International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by permission.

[ 20 ] The tempo remains at ♩ = ca.100, so the number of notated beats between pulses remains the same. As in Example 3, solid boxes indicate ATHs; those labeled ⑤ and ⑥ relate by T6 (the numbers for ATHs start over in this example). The remaining ATHs, labeled ①−④ and ⑦, appear partly or entirely in the ringing changes texture, in anticipation of the coda. Unlike the coda, however, here the ringing changes ATHs appear at a variety of dynamic levels, from p to ff. This creates instability and momentum toward the piece’s final loud attacks (m. 125 sff, m. 130 ff) before the slower and uniformly quiet coda. The waveform graph offers visual confirmation of this point (Example 2, second to last red box).

[ 21 ] The final single-note appearances of the tritone-free hexachords prior to the coda are remarkable for their subtlety, completeness, and summarizing power. In mm. 123−25, T6-related [013458] hexachords appear on the surface in registral order rather than the usual temporal order. That is, the lowest six pitches (F2, A2, C3, C♯/D♭3, A♭3, B♭3) of the passage in dashed boxes form a [013458] member, as do the highest six pitches. The registral ordering permits Carter to emphasize the hexachord’s excluded interval, the tritone, via temporal order through the adjacencies <E4, B♭3>, <F2, B5>, <D4, A♭3>, <A2, D♯6> (the guitar sounds one octave lower than written). In addition, Example 5 examines a remarkable passage just prior to the coda.

Example 5

Elliott Carter, Changes, mm. 127−128, overlapping statements of tritone-free hexachords

[ 22 ] The top line of the example reproduces the pitches enclosed within dashed boxes in Example 4, mm. 127−28 (first box only in m. 128). The complete pitch-class aggregate is present, with non-overlapping [023457] hexachords related by T6. As an ordered series of pitch-classes, no all-interval series is present, since the first five ordered pitch-class intervals <T5E38> reappear as the last five. However, ten of the eleven unordered pitch intervals within the span of one octave are present, as indicated above the top line of the example (unordered pitch interval 7 appears twice, and unordered pitch interval 6 is absent). This “catalog” of intervals alludes to the latent all-interval property of this aggregate.(18)This is similar to what Morris (2001, 153) calls a pseudo all-interval row. Such rows can be “realized in pitch-space so that each size of interval from 1 to 11 semitones – each of the pitch-space intervals from 1 to 11 – occurs once in the realization.” In pitch-class space, if one were to preserve the ordering of the first hexachord and reverse the ordering of the second, the following all-interval series would result: pitch classes <20547391TE68>, with adjacent intervals <T5E38649172>. See Capuzzo (2007, 81−82). Finally, Carter has ordered the aggregate in time such that each adjacent segment of six pitch classes realizes one of the tritone-free hexachords.(19)This is related to what Morris (2001, 155−56) terms a supersaturated set-type row, “in which every pc in the row belongs to two imbricated row segments of the same set-class (or of two ZC-related set classes).” In all, by presenting all twelve pitch classes, ten of the eleven unordered pitch intervals within an octave, and all four tritone-free hexachords, Carter imbues this gesture with multiple summarizing agents.

[ 23 ] Let us turn to the coda, reproduced in Example 6.(20)In Example 6, parentheses in mm. 133−34 omit {A♯4, C♯5} from the second boxed [023457]; parentheses in m. 137 exclude {F2, C4} from the boxed ATH. In mm. 145−46, boxes and horizontal lines indicate an ATH formed by {G3, D4}, {D4, E4, C♯5}, and {A♭2, G3, C♮4}. For another analysis of the pitch language of the coda, see Link (2002, 10−14).

Example 6

Elliott Carter, Changes, mm. 131−150; ATHs in solid boxes; Tritone-free hexachords in dashed boxes

© Copyright 1983 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes company.

International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by permission.

[ 24 ] At the new tempo of ♩ = 67, the pulses of the 75 stream occur every 28 quintuplet sixteenth notes, while those of the 56 stream occur every 30 sixteenth notes (Poudrier 2008, 49, 59, Link n.d.). For the entire coda, each pitch appears in one register only; this is the longest such passage in the piece. Dashed boxes indicate an aggregate formed by T6-related members of [023457] (not the same members as those in Example 5, top line). As in the Example 5 passage, Carter’s realization of the [023457] hexachords alludes to their ability to form all-interval series. As indicated on Example 6 (mm. 131−34), the dyads on the musical surface form members of every interval class except 6; the “missing” 6 occurs not within the hexachords but between them, in the form of a T6 transposition. The remainder of the coda only uses the ATH. While the ringing changes texture dominates the coda, rapid single-note passages (mm. 135, 141) recall similar figuration in the music just before the coda (Example 4, mm. 126−29).

[ 25 ] With regard to surface activity occurring between pulses, the coda falls into two large sections. Measures 131−41 contain rapid single-note passages and a relatively high number of attacks in the ringing changes texture. The downbeat rest in m. 142 signals the second section, in which no rapid passagework appears and only three ringing changes attacks occur between pulses. The waveform graph in Example 2 illustrates the slowly decreasing dynamic levels that accompany this process. Dynamic levels, polyrhythm pulses, the surface activity between pulses, hexachords, and the ringing changes texture all draw attention to the coda’s decrease in attack density. The balance between familiar and unfamiliar elements tips in favor of familiar ones: rather than introduce new materials, the coda gradually strips away ones established earlier in the piece. With the trend toward quiet isolated pulses of ATHs in the ringing changes texture now complete, the piece draws to a tranquil close.

“Somewhere”

[ 26 ] The Cummings poem contains five stanzas (Cummings [1931] 1997). The waveform graph in Example 7 illustrates the relation between the stanzas and musical texture. The graph uses the recording featuring Nicholas Phan, tenor (Carter 2013).(21)I am not aware of any published research on “Somewhere.” However, Brenda Ravenscroft (2012, 2017) has published two studies of Carter works for voice composed within four years of “Somewhere.” See also Meyer and Shreffler (2008, 336−37).

Example 7

Elliott Carter, “Somewhere,” waveform graph

Red boxes indicate excerpts discussed in subsequent examples

[ 27 ] The instrumental introduction and first stanza, both marked teneramente, ♩ = 80, present sustained chords in the winds and strings. Stanza 2 remains at ♩ = 80, continues the sustained chords, and later introduces isolated single staccato notes. Stanza 3 increases the tempo to ♩ = 120 and establishes a pointillistic texture that develops the aforementioned staccato single notes. Stanza 4 continues the pointillistic texture, then restores the sustained chords last heard in stanza 2. Stanza 5 alters the tempo marking from ♩ = 120 to  = 60 (coincident with a time signature change from

= 60 (coincident with a time signature change from  to

to  ) and exclusively presents sustained chords. The coda brings back the elements of stanza 2, mixing sustained chords and staccato single notes as the tenor ends the poem, “nobody, not even the rain, has such small hands.”

) and exclusively presents sustained chords. The coda brings back the elements of stanza 2, mixing sustained chords and staccato single notes as the tenor ends the poem, “nobody, not even the rain, has such small hands.”

[ 28 ] The graph also provides an entry into Carter’s treatment of dynamics in the song. As the use of dynamics is bound up with the imagery of Cummings’s poem, let us briefly digress to examine the poem. None of the first four stanzas rhyme, but in the final stanza, the last word of each line forms an a-b-a-b rhyme scheme (“closes,” “understands,” “roses,” “hands”). The first of these words, “closes,” along with the immediately following “opens,” forms the principal recurring image of the poem. In the first stanza, the “most frail gestures” of the beloved “enclose” the speaker. In the second, the beloved’s “slightest look easily will unclose” the speaker, who continues, “though i have closed myself as fingers, you open always petal by petal myself.” In the third stanza, the speaker states, “if your wish be to close me, i and my life will shut very beautifully, suddenly.” Only the fourth stanza lacks any explicit reference to closing or opening. The final stanza begins, “i do not know what it is about you that closes and opens.” “Roses,” the word that rhymes with “closes,” represents another recurring idea in the poem, presented as floral images (petals, roses, flowers) and as words associated with nature (Spring, snow, rain).

[ 29 ] As the waveform graph in Example 7 reveals, Carter’s use of dynamics creates a musical representation of the poem’s opening/closing motif. The instrumental introduction begins softly, grows louder, then returns to a soft dynamic level. In other words, the dynamic level “opens,” then “closes.” The excerpt from stanza 1 likewise opens then closes, while the excerpt from stanzas 2−3 closes then opens. The song’s most drastic closing of dynamics occurs immediately before the coda; the gesture exaggerates the more modest openings and closings that precede it.

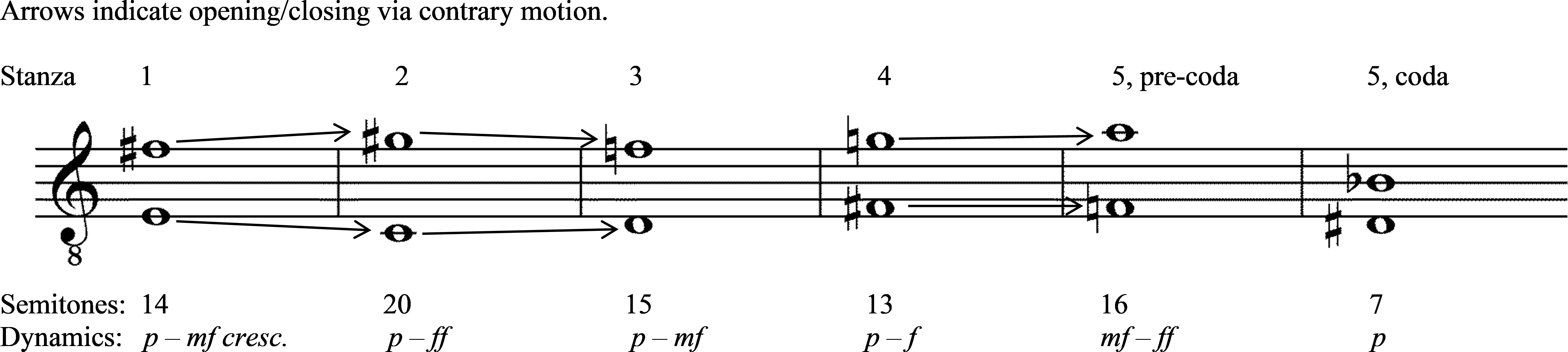

[ 30 ] The large melodic construction of the vocal line also exhibits opening and closing involving dynamics and register. Example 8 provides a sketch.

Example 8

Elliott Carter, “Somewhere,” lowest and highest vocal pitches and vocal dynamics of each stanza

[ 31 ] In the first stanza, the tenor part resides within a dynamic range of p to mf cresc. The range of stanza two “opens” from p to ff. Stanza three “closes,” p to mf. Stanza four opens from p to f, stanza five opens further from mf to ff, and the coda closes, residing exclusively at the p dynamic. Notably, the loudest dynamic level of a stanza often coincides with an important word in the poem. Examples include “things which enclose” (stanza 1), “first rose” (stanza 2), and “deeper than all roses” (stanza 5).

[ 32 ] A second aspect of opening and closing in the vocal part involves the lowest and highest pitches of each stanza. I shall refer to the lowest pitch as the floor, the highest pitch as the ceiling, and the interval between them measured in semitones as the height. For instance, the height of the first stanza pitches is 14, since the floor is E3, the ceiling is F♯4, and the interval from E3 to F♯4 is 14 semitones. The height increases (opens) in the second stanza to 20. Because the second stanza’s floor and ceiling are approached by expanding contrary motion, the first stanza’s floor and ceiling are “enclosed by” those of the second stanza.(22)Morris (1998) offers a formal study of contrapuntal motion in a post-tonal context. The height of the third stanza decreases (closes) to 15, and since the floor and ceiling are approached by contracting contrary motion, the second stanza’s floor and ceiling “enclose” those of the third. The pattern of opening-then-closing breaks at this point, because the height decreases once again in the fourth stanza. As the floor and ceiling of the fourth stanza are approached by similar motion, no enclosure takes place. The pattern of opening-then-closing then resumes in the fifth stanza, opening to 16 in the music before the coda, and closing to 7 in the music within the coda. As with the loudest dynamic level of a stanza, Carter often uses the highest pitch of a stanza to emphasize a motif in the poem. Examples include “enclose me” in stanza 1, “Spring opens” in stanza 2, and “deeper than all roses” in stanza 5. As noted earlier, “enclose” and “deeper than all roses” also feature the loudest dynamic levels of their respective stanzas.(23)Since the height of two moving voices can only increase, decrease, or remain the same, any change in height could potentially be interpreted as opening or closing, at least in the abstract. But by being selective and attuned to musical and textual context, I hope to demonstrate that changes of height are not trivial.

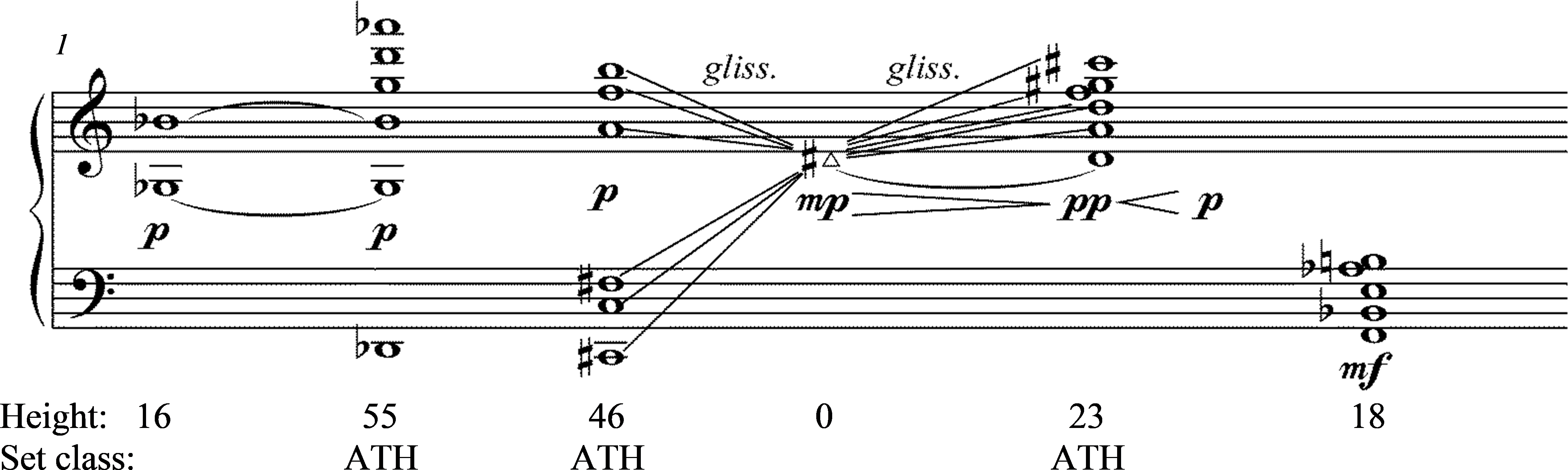

[ 33 ] Having made some large-scale observations about the role of dynamics and pitch in the enactment of opening, closing, and enclosure in “Somewhere,” let us now turn to close readings of representative excerpts. Example 9 provides a short score of the instrumental introduction, which establishes the techniques of opening and closing heard throughout the song.

Example 9

Elliott Carter, “Somewhere,” instrumental introduction, mm. 1−8, analysis

Triangular notehead indicates orchestral unison

[ 34 ] The song begins with a quiet sustained dyad, {G♭3, B♭4}. As it sounds, one pitch enters below it and three above it; all six pitches form an ATH at the dynamic level of p. The expanding contrary motion from the dyad to the ATH creates an enclosure analogous to those in the vocal part.(24)I say “analogous to” because there are important differences. Here we have a voice leading from a dyad to a hexachord; the prior ones only involved dyads. In addition, the hexachord repeats the dyad. In the process, the height increases more than threefold, from 16 to 55 semitones. Two representations of “closing” then follow. First, the 55 semitone ATH leads via oblique motion to a 46 semitone one. Then, the 46 semitone ATH leads by contracting contrary motion and glissando in each instrument to a D♯4 orchestral unison (triangular notehead), marked mp decr. Because we hear the entire pitch space close microtonally in the approach from the 46 semitone ATH to the D♯4 unison, the glissando produces an especially vivid version of enclosure. A glissando from D♯4 then leads via oblique motion to a 23 semitone ATH, marked pp, cresc., p. The concluding five-note sonority (an abstract subset of the ATH set class) is set off by its unique mf dynamic marking, its low ceiling (B3), and its approach via similar motion, the only such motion in the excerpt. In what follows, I analyze the interactions of height, opening, closing, and enclosure with Carter’s setting of the poem.

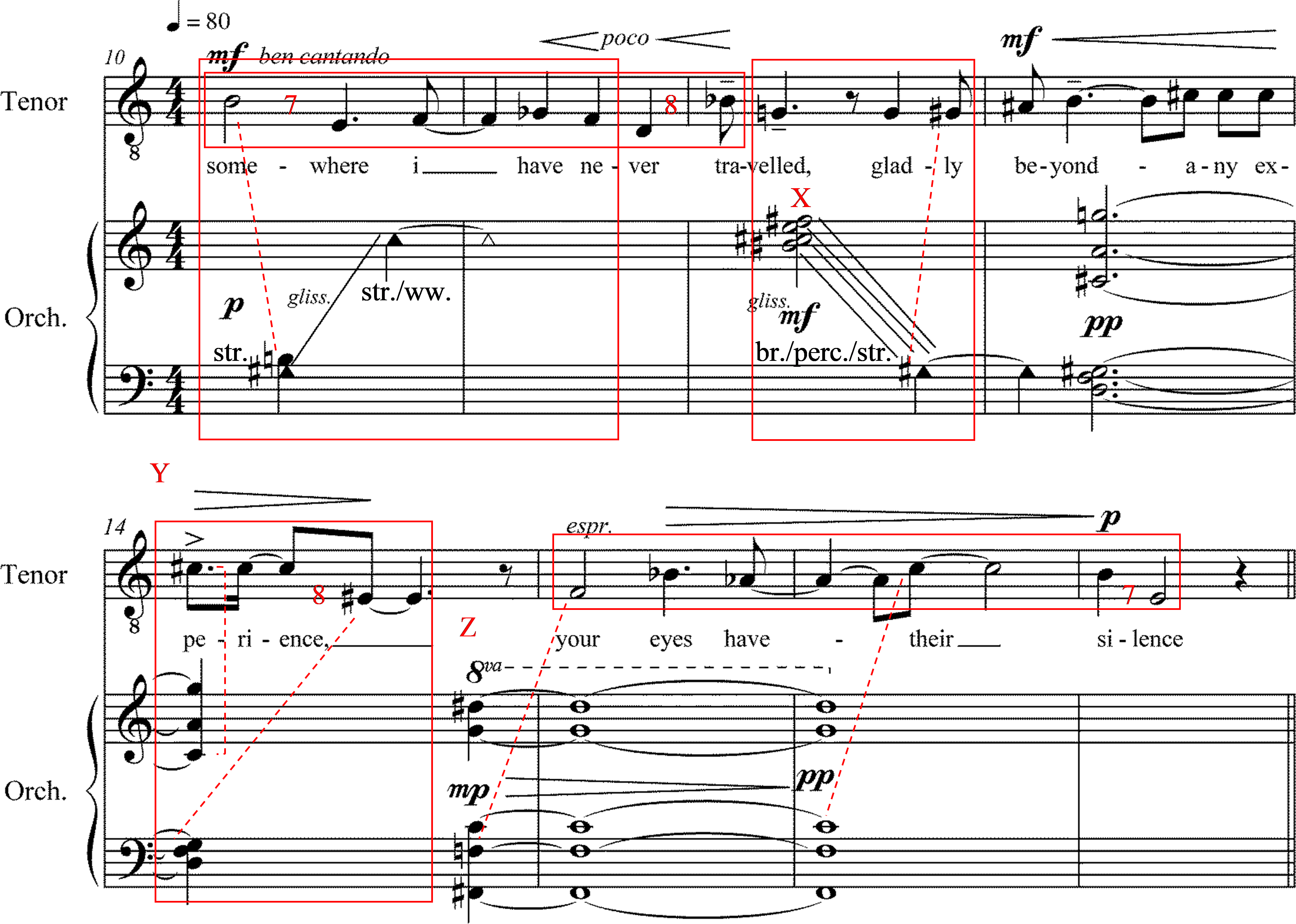

[ 35 ] Example 10 shows Carter’s setting of the first two lines of stanza 1. The vocal pitches and vocal rhythms are reproduced in full; the orchestral reduction shows pitches in their relative rhythmic positions within each measure.

Example 10

Elliott Carter, “Somewhere,” stanza 1, lines 1−2

Triangular noteheads indicate orchestral unisons; Dashed lines indicate shared pitches;

Solid boxes indicate ATHs

© Copyright 2010 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes company.

International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by permission.

[ 36 ] The accompaniment employs the techniques of opening, closing, and enclosure established in the introduction. The stanza begins with a G♯3 unison that leads via glissando in the strings to a C5 unison. In m. 12, a [0146] all-interval tetrachord (henceforth AIT) then repeats and encloses C5 (respelled as B♯4), followed by a return to the G♯3 unison, approached in the strings by glissando. The sonorities thus open from C5 to the AIT via enclosure, then close from the AIT to G♯3 (heights 0, 6, and 0 respectively). A series of enclosures via expanding contrary motion concludes the excerpt: the sonority marked X is enclosed by Y, and Y is enclosed by Z. Throughout the excerpt, the orchestral dynamic levels alternately open and close (p, mf, pp, mp, pp).

[ 37 ] Amid this activity in the orchestra, the sizes of the voice’s largest leaps open from 7 to 8 (“somewhere” and “never travelled”), then close from 8 to 7 (“experience” and “silence”). The 7-semitone leaps set the first and last words of the excerpt and use the same pitches, <B3, E3>, creating a melodic frame. As indicated by dashed lines on the example, frequent shared pitches form a salient means of interaction between the tenor and the orchestra.

[ 38 ] Example 11 reproduces the end of the second stanza and the start of the third. As in Example 10, vocal pitches and rhythms appear in full, while the orchestral reduction shows pitches in their relative rhythmic positions within each measure.

Example 11

Elliott Carter, “Somewhere,” end of stanza 2 and beginning of stanza 3

Triangular noteheads indicates orchestral unisons; Dashed lines indicate shared pitches;

Brackets in tenor part indicate ATH

© Copyright 2010 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes company.

International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by permission.

[ 39 ] In order of appearance, the heights of the orchestral sonorities are <38, 65, 54, 15, 20, 44, 68, 0, 18> (repetitions omitted). Save for the oblique motions from 65 to 54, and from 15 to 20, each sonority encloses or is enclosed by the following one. Carter places the enclosure with the greatest change in height (68 to 0) at the junction of the stanzas, coinciding with a tempo change and a drop in dynamics from f to p. Throughout the excerpt, Carter coordinates changes in the heights of orchestral sonorities, dynamic levels, and vocal register in a striking manner. “Spring opens” is set to “tall” orchestral sonorities, a relatively high vocal register (C♭4 and higher), and relatively loud dynamics in all parts (mf and above). In contrast, the parenthesized words “touching, skilfully [sic], mysteriously” are set to “shorter” sonorities, a lower vocal register, and softer dynamics – an instance of “closing” in multiple parameters. Orchestral height, vocal register, and dynamic levels then open in tandem at “her first rose,” then close again at “or if your wish.” With regard to the vocal line, three features that were also present in Example 10 are the numerous shared pitches with the orchestra (dashed lines), an ATH formed by the tenor alone, and a melodic frame created by repeated pitches: <A♭4, (G♭4), C♭4> sets “Spring opens” and <B3, G♯4> sets “her first,” both at the dynamic level of f.

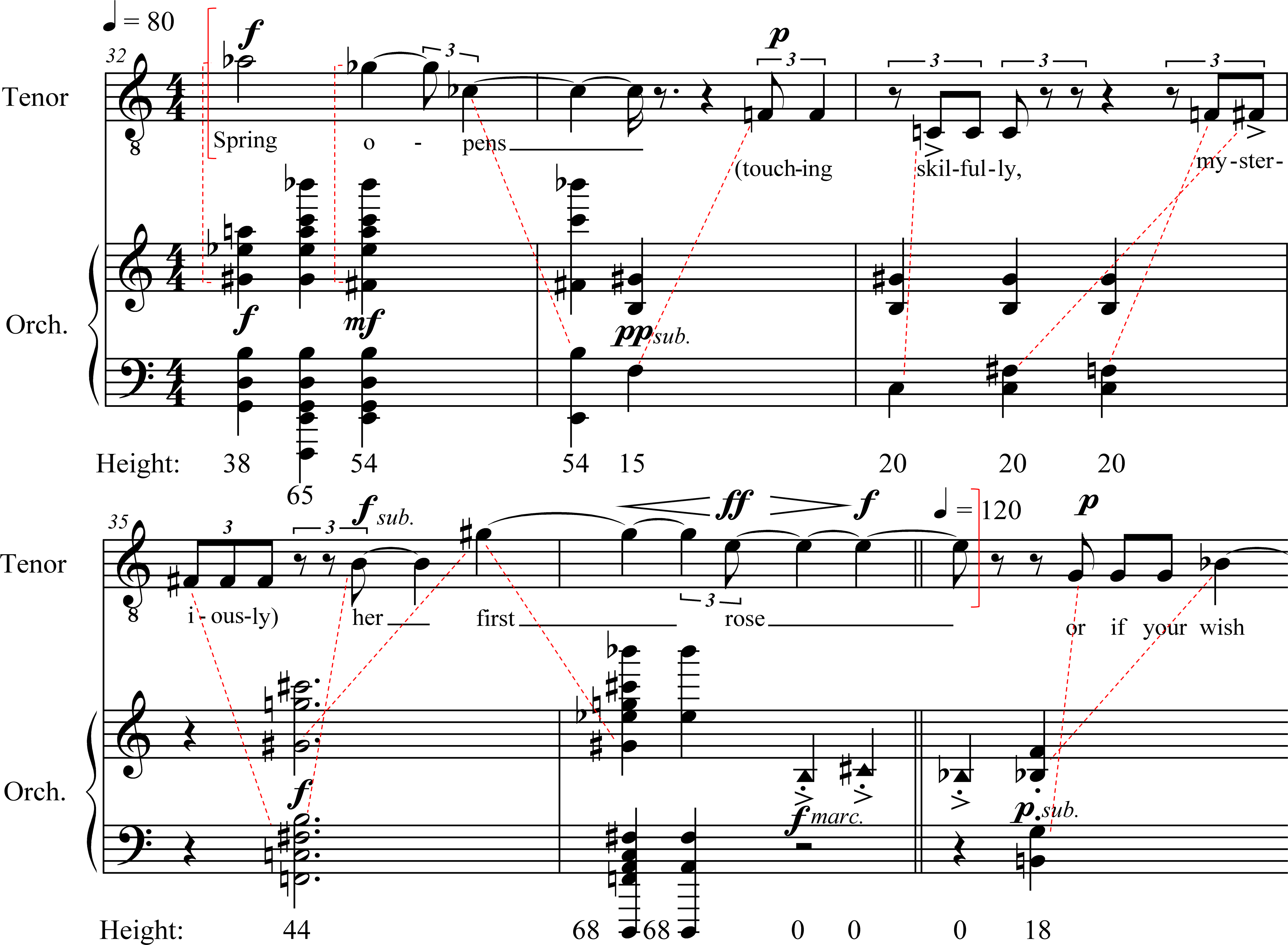

[ 40 ] We now have sufficient context for understanding the quiet coda. Example 12 reproduces it along with the four measures that precede it. Here the rhythm in the orchestral reduction appears exactly as notated in the score.

Example 12

Elliott Carter, “Somewhere,” closing measures

Triangular notehead indicates orchestral unison;

Dashed lines indicate shared pitches;

Solid box in tenor indicates ATH

© Copyright 2010 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes company.

International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by permission.

[ 41 ] The setting of “all roses” forms the song’s climax and features the tenor’s highest pitch, A4, and loudest dynamic level, ff. The orchestral sonorities’ heights open from 49 to 63, then close from 63 to 0, alighting on a unison D4 (woodwinds/strings). Dynamic levels, pitch heights, and vocal register then fall abruptly and in tandem. Like the preceding loud orchestral sonorities, the closing quiet ones first open, then close (heights 0, 11, 3). Through the combination of these elements, the quiet ending of “Somewhere” provides the piece’s most dramatic musical portrayal of the poem’s motifs of opening, closing, and enclosure. However, despite the presence of these familiar elements, the ending comes across as new and fresh to my ear, strongly set apart from the preceding music. Carter sets “nobody, not even the rain, has such small hands” as a hushed vocal solo punctuated by two quiet, short attacks in the strings. By delaying the singer’s only solo until the final measures, Carter imparts a degree of unfamiliarity to the quiet ending of “Somewhere.”

Conclusion

[ 42 ] The freshness and vitality of Carter’s endings has long garnered praise from scholars and musicians. Oliver Knussen (1999) writes that “some of Carter’s most audacious invention is to be found in his codas!” Bayan Northcott points to Carter’s “genius for unexpected endings” (1999), and Richard Wilson states, “There is no predicting how [Carter’s works] will begin, and how they end is only marginally less surprising” (2008, 76). In this paper, I have focused on a particularly common type of ending for Carter, one that involves a loud climactic attack followed by a quiet passage or section. In the Introduction, I raised the questions of “why” and “how” with regard to these endings. Regarding the “how,” I hope that the diversity of methodologies employed in this paper—analysis of contour, intervals, and silence for Mnemosyné; analysis of hexachords and long-range polyrhythm for Changes; and analysis of pitch range, dynamic range, and text/music relations for “Somewhere” – may begin to illuminate the roles of different musical parameters in the quiet endings. The balance or imbalance of familiar and unfamiliar parameters offers objective data for the subjective interpretation of a given ending’s musical character. With more work on this topic, we may eventually approach a preliminary general understanding of the “how” of Carter’s quiet endings. In addition to the aforementioned Piano Concerto and Allegro Scorrevole, future research might take “Dies Irae” from In Sleep, In Thunder and Remembrance and Anniversary from Three Occasions for Orchestra (1986−1989) as starting points. We will then be in a better position to consider some significant related questions: Why did the quiet endings become “virtually a defining feature of Carter’s late music,” as Meyer and Shreffler (2008, 294) point out? How do the narrative arcs of these pieces differ from those in Carter’s pieces that do not end in this manner? Such questions, while imposing in scope, point the way to a deeper understanding of Carter’s musical legacy.

Footnotes

1. Stone (1969, 572), Meyer and Shreffler (2008, 294), Wilson (2008, 76).

2. To the best of my knowledge, there are no published analytic studies of Mnemosyné. On August 28, 2017, Boosey & Hawkes issued a revision notice indicating that the third note in m. 7 should be F4, not G4.

3. Given the absence of staccato markings, the presence of accents, and the loud dynamic levels, it is reasonable to ask if staccato entry 3 is not a staccato entry at all, but instead part of the legato music. Readers with access to the score of Mnemosyné can quickly confirm that these measures (and the silence before and after them) continue the pattern of alternating legato and staccato characters maintained throughout the piece.

4. Of course, many other factors bear on one’s experience of the quiet ending, perhaps beginning with one’s familiarity with Carter’s music more generally.

5. I am grateful to an anonymous reader for this insight.

6. A more detailed account of the two characters in Mnemosyné might discuss a) the prominent role of cross-cutting (Schiff 1998, 39) in mm. 34−53 and b) the numerous set-class relations among legato entries 1−2 and the final staccato entry. These relations involve the all-interval tetrachords [0146] and [0137], the all-trichord hexachord [012478], and the eight-note collection [0124678T]. Throughout this paper, square brackets [ ] indicate set classes, angle brackets < > indicate ordered sets, and curly brackets { } indicate unordered sets.

7. Wilson (2008) discusses the beginnings and endings of several Carter pieces. Link (2012, 51) and Schiff (1998, 90) discuss the ending of Carter’s String Quartet No. 4. On codas by other post-tonal composers, see Casken (2001) on Lutosławski and McLean (2009) on Schoenberg.

8. Mead (2012; 2016) and Link (1994) study the relation between polyrhythm pulses and the musical surface in several Carter compositions.

9. General sources on Changes include Schiff (1998, 136−38) and Kozinn (1984, 1−4). Discussions of the piece’s pitch language include Link (2002, 10−14) and Capuzzo (2000; 2004; 2007). Discussions of the piece’s long-range polyrhythm include Link (1994, 111−13), Link (n.d.), and Poudrier (2008, 74−91 and 117−23).

10. In the preceding sentences, and throughout this paper, “member” is used as a synonym for “pitch-class set.”

11. This is a result of the well-known hexachord theorem, first proven in Lewin (1960).

12. Poudrier (2008, 55) and Capuzzo (2000, 43−44) offer accounts of the piece’s form that complement that of Schiff.

13. A discussion of this passage, along with Carter’s sketch for it, appears in Capuzzo (2004, 9−10).

14. The recurring realizations of the ATH as the union of two trichords might suggest that Carter is taking full advantage of the all-trichord property, but in fact only seven of the ten possible trichord unions are present. See Link (2002,14) and Carter (2002, 241).

15. The tempo, specifically, is 100.5, so that the closing tempo of ♩ = 67 is precisely two-thirds as fast.

16. More precisely, “ATH x aligns with a pulse” means that one of the attacks in a given ATH formation coincides with a pulse.

17. Three features of Example 4 merit discussion. First, pulse 58/75 is not attacked. Second, in a departure from the fixed pitches that characterize the ringing changes texture, pitch-class 6 appears in two registers during mm. 116−22, as G♭4 (m. 116) and F♯2 (m. 119−22) (the guitar sounds one octave lower than written). Likewise, pitch-class 5 appears as F3 (mm. 116−17) and F4 (mm. 121−22). Finally, parentheses in mm. 128−29 indicate that B3 is not part of the [013458].

18. This is similar to what Morris (2001, 153) calls a pseudo all-interval row. Such rows can be “realized in pitch-space so that each size of interval from 1 to 11 semitones – each of the pitch-space intervals from 1 to 11 – occurs once in the realization.” In pitch-class space, if one were to preserve the ordering of the first hexachord and reverse the ordering of the second, the following all-interval series would result: pitch classes <20547391TE68>, with adjacent intervals <T5E38649172>. See Capuzzo (2007, 81−82).

19. This is related to what Morris (2001, 155−56) terms a supersaturated set-type row, “in which every pc in the row belongs to two imbricated row segments of the same set-class (or of two ZC-related set classes).”

20. In Example 6, parentheses in mm. 133−34 omit {A♯4, C♯5} from the second boxed [023457]; parentheses in m. 137 exclude {F2, C4} from the boxed ATH. In mm. 145−46, boxes and horizontal lines indicate an ATH formed by {G3, D4}, {D4, E4, C♯5}, and {A♭2, G3, C♮4}. For another analysis of the pitch language of the coda, see Link (2002, 10−14).

21. I am not aware of any published research on “Somewhere.” However, Brenda Ravenscroft (2012, 2017) has published two studies of Carter works for voice composed within four years of “Somewhere.” See also Meyer and Shreffler (2008, 336−37).

22. Morris (1998) offers a formal study of contrapuntal motion in a post-tonal context.

23. Since the height of two moving voices can only increase, decrease, or remain the same, any change in height could potentially be interpreted as opening or closing, at least in the abstract. But by being selective and attuned to musical and textual context, I hope to demonstrate that changes of height are not trivial.

24. I say “analogous to” because there are important differences. Here we have a voice leading from a dyad to a hexachord; the prior ones only involved dyads. In addition, the hexachord repeats the dyad.

Works Cited

Capuzzo, Guy. 2000. “Variety Within Unity: Expressive Ends and Their Technical Means in the Music of Elliott Carter, 1983−1994.” Ph.D. diss., University of Rochester.

________. 2004. “The Complement Union Property in the Music of Elliott Carter.” Journal of Music Theory 48, no. 1: 1−24.

________. 2007. “Registral Constraints on All-Interval Rows in Elliott Carter’s Changes.” Intégral 21: 79−108.

Carter, Elliott. 1983. Changes. Boosey & Hawkes/Hendon Music SRB-15.

________. 1994. Elliott Carter: Eight Compositions (1948−1993). Bridge Records BCD 9044.

________. 2002. Harmony Book. Ed. Nicholas Hopkins and John F. Link. New York: Carl Fischer.

________. 2013. Elliott Carter: 103rd Birthday Concert (Live). NMC Recordings NMCDVD193.

Casken, John. 2001. “The Visionary and the Dramatic in the Music of Lutosławski.” In Lutosławski Studies. Ed. Zbigniew Skowron. 36−56. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cummings, E.E. [1931] 1997. ViVa. New York: Liveright.

Knussen, Oliver. 1999. Program notes for Elliott Carter: Symphonia · Clarinet Concerto. Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Hamburg 459660-2.

Kozinn, Allan. 1984. “Elliott Carter’s Changes.” Guitar Review 57: 1−4.

Lewin, David. 1960. “Re: The Intervallic Content of a Collection of Notes, Intervallic Relations between a Collection of Notes and Its Complement: An Application to Schoenberg's Hexachordal Pieces.” Journal of Music Theory 4, no. 1: 98−101.

Link, John F. n.d. Unpublished polyrhythmic analysis of Elliott Carter, Changes.

________. 1994. “Long-Range Polyrhythms in Elliott Carter’s Recent Music.” Ph.D. diss., City University of New York.

________. 2002. “The Combinatorial Art of Elliott Carter’s Harmony Book.” In Elliott Carter, Harmony Book. Ed. Nicholas Hopkins and John F. Link. 7−22. New York: Carl Fischer.

________. 2012. “Elliott Carter’s Late Music.” In Elliott Carter Studies, Ed. Marguerite Boland and John Link. 33−54. New York: Cambridge University Press.

McLean, Don. 2009. “A Chronology of Intros, an Enthrallogy of Codas: The Case of Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony, Op. 9.” In Schoenberg’s Chamber Music, Schoenberg’s World. Ed. James K. Wright and Allan M. Gillmor. 97−132. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press.

Mead, Andrew. 2012. “Time Management: Rhythm As a Formal Determinant In Certain Works of Elliott Carter.” In Elliott Carter Studies, Ed. Marguerite Boland and John Link. 33−54. New York: Cambridge University Press.

________. 2016. “Fuzzy Edges: Notes on Musical Interaction in the Music of Elliott Carter.” Elliott Carter Studies Online 1.

Meyer, Felix and Anne C. Shreffler. 2008. Elliott Carter: A Centennial Portrait in Letters and Documents. Suffolk: The Boydell Press.

Morris, Robert D. 1998. “Voice-Leading Spaces.” Music Theory Spectrum 20, no. 2: 175−208.

________. 2001. Class Notes for Advanced Atonal Music Theory, Vol. 1. Lebanon, NH: Frog Peak Music.

Northcott, Bayan. 1999. Program notes for Elliott Carter: Symphonia · Clarinet Concerto. Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Hamburg 459660-2.

Poudrier, Ève. 2008. “Toward a General Theory of Polymeter: Polymetric Potential and Realization in Elliott Carter’s Solo and Chamber Instrumental Works After 1980.” Ph.D. diss., City University of New York.

Ravenscroft, Brenda. 2012. “Layers of Meaning: Expression and Design in Carter’s Songs.” In Elliott Carter Studies, Ed. Marguerite Boland and John Link. 271−91. New York: Cambridge University Press.

________. 2017. “An Adventure in Form: Elliott Carter’s “Like a Bulwark” (2009).” Elliott Carter Studies Online 2.

Schiff, David. 1988. “Elliott Carter’s Harvest Home.” Tempo 167: 2−13.

________. 1998. The Music of Elliott Carter, 2nd ed. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Stone, Kurt. 1969. “Current Chronicle.” Musical Quarterly 55, no. 4: 559−72.

Wilson, Richard. 2008. “Beginnings and Endings – Plus A Conversation.” In Elliott Carter: A Centennial Celebration. Ed. Marc Ponthus and Susan Tang. 75−97. Hillsdale, N.Y.: Pendragon Press.