“Workshop Minnesota”: Elliott Carter’s Analysis of Luigi Nono’s Il canto sospeso*

I would like to thank Felix Meyer (Director of the Paul Sacher Stiftung) and Angela Ida De Benedicts (Scholarly Staff, Department Member at the PSS) for their support and invaluable insights about the works and lives of Elliott Carter and Luigi Nono. Also, I would like to thank the Amphion Foundation for permission to publish Carter’s lecture. Lastly, many thanks to Erin George, the Research Services Archivist at the University of Minnesota Archives, for providing me with the archival materials pertaining to Elliott Carter’s 1967 residency at the University of Minnesota.Laura Emmery

Introduction

[ 1 ] In July 1967, Elliott Carter led the Contemporary Music Workshop at the University of Minnesota for its “Summer Music at Minnesota” program. As a week-long guest-lecturer for the Music 60 summer course, “An Introduction to Orchestra Repertoire,” Carter presented nine seminar sessions on four topics: “Basic needs for a music situation that is alive,” “The symphony orchestra—a relic of the past or a possible active force for new music?,” “Can an established musical form like the concerto have any relevance today?,” and “How to live with the musical present.”(1)University of Minnesota Historical Newspaper Collection, Minneapolis Tribune, Sun., June 25, 1967. These lectures were recorded on reel-to-reel tapes and are now part of the Elliott Carter Collection of the Paul Sacher Stiftung.

[ 2 ] One of the most telling lectures is Carter’s July 6 discussion of Luigi Nono’s Il canto sospeso (1955-56). Carter heard the performance of the piece at the twenty-third Festival of Contemporary Music of the Venice Biennale Festival in 1960, under the baton of Bruno Maderna (Mila 1975, 382; Nielinger 2006, 83), where his own Second String Quartet was also performed.(2)Carter’s Second String Quartet (1959) was performed by the Juilliard String Quartet on September 15, 1960, and Nono’s Il canto sospeso was performed on September 17, 1960. I would like to thank Angela Ida De Benedictis for providing me with the information regarding the XXIII Festival of Contemporary Music of the Venice Biennale Festival (1960). The piece left such a strong impression on Carter that he proclaimed Il canto sospeso to be “one of the best works... that has been written since the war by a European” (Guberman 2015, 78) and in his 1963 lectures series at Dartmouth University, Carter praised the piece as a true “masterpiece” (Carter 1965 and Bernard 1997, 17).

[ 3 ] Despite Carter’s ambivalence about serialism, he nonetheless studied the method and many important twelve-tone works that he admired. In addition to Nono’s Il canto sospeso, Carter also praised Walter Piston’s First Symphony for masterfully integrating elements of the twelve-tone technique (Carter 1946, 165-67) and was inspired by Schoenberg’s Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31 to write his own Variations for Orchestra (1955). Even though Carter explained that his study of the method was “out of interest and out of professional responsibility” (Carter 1960 and Bernard 1997, 219-220), he showed a great dedication to learning the method by reading the works of René Leibowitz, Ernst Krenek, and Joseph Rufer, as well as through his own analysis of Schoenberg’s Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31.(3)A draft of Carter’s radio lecture on Schoenberg’s Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31 is published in Meyer and Shreffler 2008, 141-47.

[ 4 ] In addition to studying the method, personal letters and sketches reveal that Carter tried to implement the twelve-tone system in his own works. For instance, in his 1959 letter to Goffredo Petrassi, Carter admits encountering “serious conceptual difficulties” while writing the Second String Quartet (1959), and thus trying out the twelve-tone method as a solution (Meyer and Shreffler 2008, 158). Sketches for the Second Quartet and other works composed during the 1950s (such as his Variations for Orchestra) show Carter working with twelve-note rows.(4)For instance, see Schmidt 2012, 183-84, and Emmery 2017. Other scholars have found evidence of Carter experimenting with the method as early as the 1940s. Felix Meyer notes that in the first movement of the unfinished Sonatina for Oboe and Harpsichord (sketched as early as 1947), Carter derives the pitch structure of both instruments from a single twelve-tone row (Meyer 2012, 225), while Stephen Soderberg references a “row” written on the pages of sketches for the 1944 Holiday Overture (Soderberg 2012, 242).

[ 5 ] However, rather than admiring the method itself, Carter tends to focus on the expressive character of music composed using this technique. Hence, in this Nono lecture, as well as in his previous lectures on other twelve-tone pieces, such as Schoenberg’s Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31, Carter’s engagement with the technical details of the method is limited to discussing the basic row and its four principal transformations – transposition, inversion, retrograde, and retrograde inversion.(5)Also see Carter’s letter to William Glock, dated May 3, 1957, in which Carter expresses surprise and seems reluctant to accept Glock’s invitation to give a detailed analysis of Schoenberg’s Variations, Op. 31 at the 1957 Dartington Summer School festival, because his understanding of Schoenberg’s technique is rather general, and noting that the talk he gave on Schoenberg on a previous occasion in 1957 for the CBC Vancouver radio station was “one for lay listeners and explained rather simply the devices Schoenberg used in that work” (Meyer and Shreffler 2008, 148-49; 140). Ultimately, Carter gave a lecture on Schoenberg’s Variations, Op. 31 and Stravinsky’s Agon (Meyer and Shreffler 2008, 147). Instead, Carter expresses his admiration for the ability of the singers to meet the composition’s technical demands, as well as for the ways Nono uses the system to convey the message and the somber character of the piece.

[ 6 ] In his “Workshop Minnesota” lecture on Nono, Carter shows an intimate familiarity with Il canto sospeso and other works by Nono, as well as a thorough understanding of Nono’s compositional techniques. However, some details of the talk suggest that Carter most likely read Reginald Smith Brindle’s 1961 analysis of the second movement of Il canto sospeso, the very same movement Carter analyzes in his talk.(6)Reginald Smith Brindle, “Current Chronicle: Italy,” The Musical Quarterly 47, no. 2 (April 1961): 247-255. In this article, for instance, Smith Brindle identifies eleven distinct systems of dynamic markings in the piece, which Carter reiterates in his own talk, but neither Smith Brindle nor Carter mention that Nono uses one of the markings, ppp, twice in this plan for this movement, ultimately creating twelve dynamics elements.(7)Bailey (1992, p. 291) corrects the error. Bailey argues that Smith Brindle applied Nono’s general system of dynamics to his analysis of the second movement, without discerning the specifics of the method as it is applied throughout the movement. She goes even further in making a scathing comment regarding Smith Brindle’s entire analysis of the piece, nothing that “Not only has [Smith Brindle] made assertions about the whole work on the basis of his analysis of a single movement; it now becomes clear that his remarks about that movement are based on his analysis of the first two bars” (pp. 290-91). Further, other than identifying this system of dynamics, Smith Brindle’s observations about how Nono actually uses the dynamic series are rather vague, only noting that “each of these eleven dynamic values is distributed according to a permutational plan, which hardly concerns us here.” Smith Brindle concludes that it is not the actual technique of an “arbitrary method,” but rather how such method “results in actual performance,” that is of concern to him, and as we shall see, is also of a concern to Carter.(8)Smith Brindle, 254. For details on how the order of the dynamic indications is determined through rotations in the second movement of Nono’s Il canto sospeso, see Bailey pp. 291-93.

[ 7 ] Nonetheless, the July 6, 1967 session, transcribed and edited below, is quite significant as it is one of the two known public lectures in which Carter discusses the details of Nono’s compositions and methods, the other being his 1963 Dartmouth lecture. While both lectures are similar in nature – Carter addresses the text, which is based on Thomas Mann’s collection of letters from the Nazi concentration camps; the expressive nature of the piece emerging from sudden shifts in registers and dynamics; and Nono’s techniques of serializing rhythm, dynamics, and pitch – Daniel Guberman suggests that Carter’s opinion of Il canto sospeso soured somewhat between 1963 and 1967.(9)See Guberman, 2012, 116-122; 129-30. In the 1967 Minnesota lecture, Carter describes Nono’s serial technique as “an artificial order” that lacks thematic material (§3), resulting in music that has no sense of shape, and that therefore all sounds the same (§26).

[ 8 ] Despite these criticisms of the piece, Carter still refers to Il canto sospeso as a composition of “extraordinary promise” and a “truly remarkable achievement,” and offers a detailed analysis of the second movement. Although a recording of the piece was not commercially available until 1988 and the piece had not yet been performed in the United States, Carter made a tape recording of a performance that was broadcast on the Italian radio on September 17, 1960. Thus, this lecture was likely the first time the workshop participants (and most anyone in the United States) had heard the piece. Playing the excerpts from the second movement while analyzing the piece at length, Carter shows his genuine admiration of Nono’s intricate technique of serializing the pitch-content, rhythm (following the Fibonacci series), and dynamics in this piece, and marvels at the auditory effect it has on listeners.

Luigi Nono’s Il canto sospeso

(excerpts from Elliott Carter’s lecture at the University of Minnesota, July 6, 1967)

[ 1 ] [Luigi Nono’s composition, Il canto sospeso] is built on what might be considered an artificial order, but produce[s] a work that, in many ways, is a very remarkable piece of musical expression. Do any of you know this work at all? Would you raise your hand? You do. Well, all right, we’ll deal with it. I’ve gotten hesitant about this.

[ 2 ] Il canto sospeso is a large choral work that was written around 1955, 1954.(10)Il canto sospeso was composed in 1955–56 and premiered in Cologne on Oct 24, 1956, by the Kölner Rundfunkchor and the Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester, conducted by Hermann Scherchen. It is built on a selection of letters from the prisoners of the Nazi war camps that Thomas Mann collected. Their letters are frightening in content, many of them by children or by wives writing to their husbands saying that they will die tomorrow. And “Il canto sospeso” means “the suspended song.”

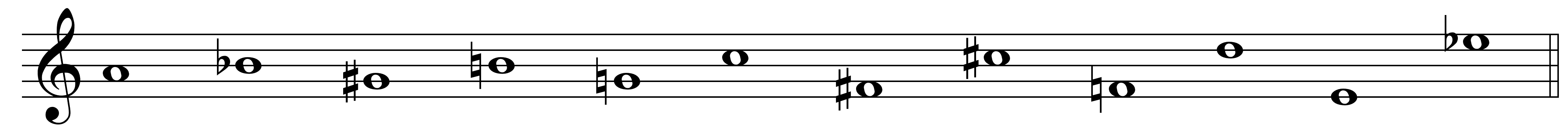

[ 3 ] This particular piece that I’m going to analyze for you is the second number. (Will you turn on the machine? I’m not sure whether this will come out visually.) The whole work is built on a twelve[-tone row]. By the time the twelve-tone system came to Luigi Nono, it was no longer the kind of thing we saw mentioned in Schoenberg – it was no longer a thematic piece of material, because he [Nono] wasn’t writing thematic music. And so that very often the twelve-tone rows were simply chromatic scales, or in this particular case, a scale that is a series of alternate chromatic scales, according to an extremely simple pattern, [Carter writes on the chalk board] like that. This is [Carter counts] 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12. So it runs from A to D♯ in ever-widening intervals. As you can see it’s one chromatic scale going downward, and another one going upward from A. [See Example 1].

Example 1

Luigi Nono, Il canto sospeso, the row

[ 4 ] The whole work is built on this [row] or on slight permutations of this row. It really doesn’t make any difference what the row of this work is, since it is not a thematic work at all. Its main characteristic is a series of just notes, separate notes, usually played by one instrument or sung by one choral part after another. And it makes clouds of sounds, each one coming in in different ways and going out – some playing short, and some playing loud – this is what you hear. It’s as if you had taken melodic lines and cut them into pieces, and sort of shredded a kind of melodic texture.

[ 5 ] On top of this row, he has imposed four or five different, what are called serial systems: an order of numbers having to do with dynamics, and note values, note lengths. So that what the piece consists of also is not [only] all these notes, but each one has a specific association with loud or soft, and with a certain length – a quarter note or a half note or a dotted eighth note. And it’s arranged in such a way that every time he goes through the row, he goes through a certain number of these other changes, but none of them are the same number as twelve, so that every time you come back to A, it will be associated with a different note length and with a different dynamic length [sic]. This is constantly being shuffled around and around and around.

[ 6 ] Now this sounds like a very mechanical thing, and if I start going into it in detail, as I will for a moment show you [in] the second movement: There are eleven systems of dynamics, which are constantly rotated.(11)See "Introduction" above, §6. Just to mention a sample of them, [Carter writes on the chalk board] there’s ppp, p, mp, mf, f. And then there’s a whole series of them in which there are crescendos from pp to mf or pp to f, and more or less of this sort of thing. And then another series in which there are diminuendos, from f to p, and that makes up eleven. So that when he [Nono] goes through the twelve notes, when he gets to the D♯ it will have the same dynamic as the first one.

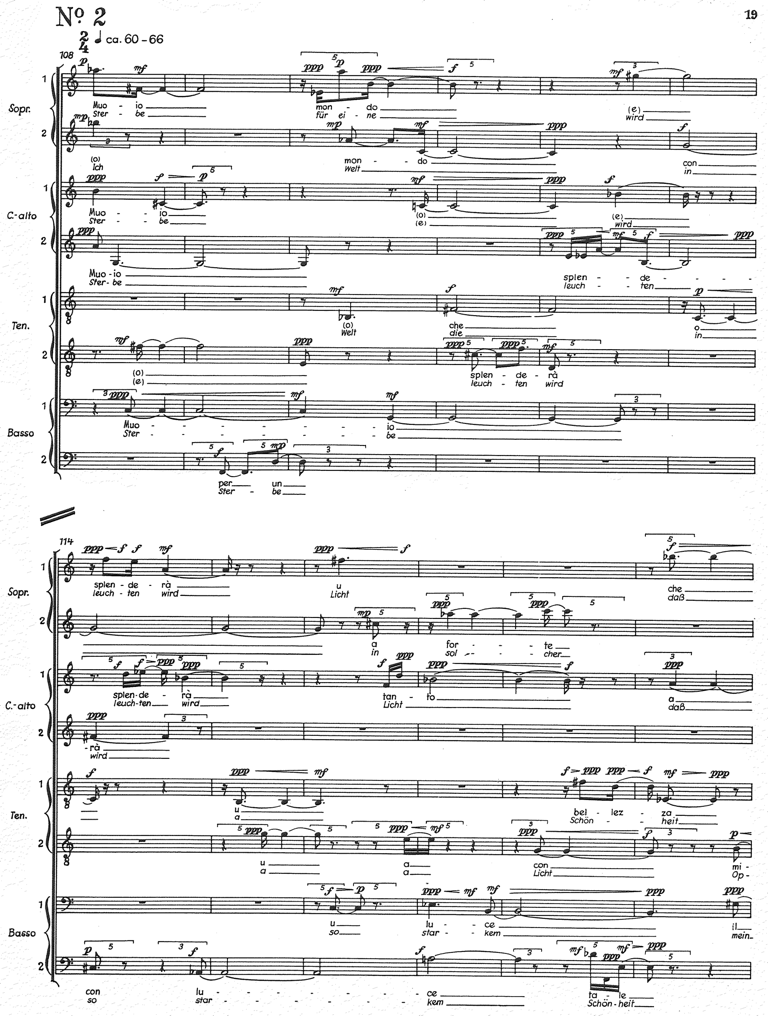

[ 7 ] Then there is a series of note values. Here’s the note “A” (Here, I’ll read it to you because you probably can’t see it.) The first time that it comes in the second movement – which I’ll play you – that note “A” is one eighth note long. The second time it comes through, after they’ve gone through that [one full statement of the row], it is two sixteenth quintuplets long; the third time, it is three quintuplets of sixteenths; the fourth time, it is five regular sixteenths; the fifth time, eight [eighth note] triplets. And what I really am reading for you is that this forms the well-known mathematical series called the Fibonacci series: 1, 2, 3, 5, 8 and it goes on I think to 10 [sic], and 13, and here it is here again. It’s in every line: 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, and then 13, 8, 5, 3, 2…. So it’s arranged in such a way that the Fibonacci series comes to its highest number, and then it starts over again with 13. And each one of these… This series runs both this way [forward] and that way [backward]. And meanwhile, there is an alteration of different note values: you see this is one eighth note, two triplets, three sixteenths, five something, eight something, thirteen something. So there’s an alteration each time of a different note value, but always with the same number, the same numerical multiplier of the series. And this one [m. 110, Soprano I] starts with 2, which is the second number of the [series], and goes 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 13, 8, 5, 3, 2, 1, and then 1, which would start over again. And similarly, here [m. 112, Contralto I], this is 3, 5, 8, 13, 13, 8, 5, 3…. And each time there’s also a succession of different note values substituted for each one of these numbers. And as you see, the dynamics…. The first time “A” comes in, it’s pp – ppp – then mp, then p, and then mp…. He’s got some kind of a pattern going, which alternates, so that each time it doesn’t read that way [forward] or that way [backward] in a regular series. So that you can see that what I have here is some shuffling of the row through – I don’t know how many times – but not more than ten times. And this is only the first three or four minutes of the piece, maybe not even that.

Example 2

Luigi Nono, Il canto sospeso, No. 2, mm. 108-19

Mainz: Ars Viva Verlag, 1956.

[ 8 ] This particular piece [movement 2] is an a cappella choral piece. And it starts with a chord: the high soprano A♭ and B♭ and the contralto on ninths [sic] below them of A♮ and B♮. Each of these notes has a different dynamic and a different…: The A♭ has a p and it’s a dotted six[teenth note]. It’s right there on the series, and it goes on.

[ 9 ] (Now if you can show this…. Maybe I can point it out a little better.) And let me say that this goes on throughout a work of almost an hour long, so that the effort of writing…. (Here is what I’m talking about, right there.) I mean, let me say: You asked me about choral music; I used to write things with dominant seventh chords and seventh chords, and when I see a chorus that has to end on this high A♭, p, this high B♭ mp, that high B♮ triple pianissimo, and that high A triple pianissimo, and jump from the high A♭ down to F♯ mf, I wonder. I’ve heard this piece played very accurately, and the record that I have is very good of it. But I must say, I never would have thought it if I hadn’t heard it. If I just saw that score I never would have thought anybody could do it. There are quite a number of choruses now in Europe and even in the United States that do things as difficult as this.

[ 10 ] Anyhow, let me just briefly give you a resumé of how this piece, again, works. This is the first note of the series [A], the B♭ is the second, the A♭ is the third, and the B♮ is the fourth, and then the fifth note is G, which is here [m. 108, Contralto 2], and the sixth note is C, which is here [m. 108, Basso 1], and each one is associated, the C, as I said, is associated in this particular case with 13 triplets of eighths, so that’s that length. This one [A♭5, m. 108, Soprano 1] is associated with three sixteenths, and it’s that length, and when F♯ comes in, it’s associated again with with mf and with, that looks like seven, or eight…. I don’t know whether it’s seven… yes it’s seven sixteenths – a note duration of seven sixteenths [sic].(12)The correct duration of the F♯ in m. 108 is thirteen sixteenths. In his haste, Carter may have counted the quarter note in m. 108 and the half note in m. 109 as six eighth notes, then added the sixteenth in m. 108 to get a total of seven sixteenths without first doubling the number of eighth notes. [eds.] So you see that this works out perfectly… one would say perfectly mechanically. And it works right on, goes right through the chromatic scale until about here, and by the time it gets here…. I think I’ve drawn a line, I don’t know if you can see it; it starts over again [in m. 110] with the A and the B♭, and the G♯, and the B♮, with a different set of dynamics and a different length, although this A, I notice…. Well, this A was an eighth note, this is three quintuplet sixteenths. So there is a constant rotation of this, and it’s like working a crossword puzzle even to analyze this piece. I don’t wish to go through this in elaborate detail – it would be too time consuming. It’s also too troublesome, too cumbersome, to get this whole thing working out. But let me play you… (Don’t take that away because we can look, at least, at the first measures.) I’m going to have quite a lot of problems because this has to be found; it’s the second piece on the reel. (You don’t have a thing that counts the revolutions? This comes at the 290th turn. Well if you’ve got revolutions it’s fine. Anyhow…)

[ 11 ] Luigi Nono was a young Italian – not so young any more – Italian composer. This work was of extraordinary promise and more than that, it was a really, I think, a remarkable achievement. It’s seldom that he’s written anything as interesting as this [piece] since, and I think one doesn’t understand this.

[ 12 ] [Audience member:] Working with Cathy Berberian on [unintelligible]

[ 13 ] Well he’s been working…. Berio, of course, is the husband, was the husband of Cathy, yes. No, Luigi Nono is actually the husband of Schoenberg’s daughter, of Nuria Schoenberg. And he lives in Venice. We see him usually when we go there. But he’s a very… a very revolutionary kind of person, both politically as well as musically. Although now, of course, this is no longer a revolution, this is already a dead letter for most young composers – nobody would bother to take the kind of trouble this must have taken to write anymore. In any case, he himself does not write…. I don’t know how he writes now. I don’t understand what he’s doing. (What is that, is that about right? Well let it be, because this is the second piece, I only know the number…. [music plays] I don’t remember how this ends. This is, in any case, I presume the instrumental introduction. [music continues]) Also let me say this piece uses... (Go on, let it run, but softly. I don’t know how far, but it’s not very much further; this is the introduction.) it uses things which nobody used very much in the orchestra: he uses a Bach trumpet that goes up to high F and G, which is a fourth or fifth above the normal C of the ordinary orchestral trumpet. It comes in with these piercing shrieks in the piece that are very striking. [music continues] (OK, let’s go on a little bit. [tape advances]. Thank you. [music plays] That may be the end of that movement [music continues], no.) But you see in a certain sense the serial order is not a terribly…. the row is not important as a thing, it’s just these isolated notes put in different positions and different octave registers. ([music continues; chorus enters] There! [music continues] We can stop and project it on the [screen]. If you can go back just enough, because it’s realy quite si[gnificant]…. I mean to have the chorus come in cold on those notes. But go on, if you can… OK. Turn it on louder so we can hear it a little bit, please. [music plays] You can turn [the projector] off. [music continues])

[ 14 ] That’s just one of eight or ten [sic] movements of this piece, but I thought the one I would like to speak about as a very interesting and striking example of what you can see seems like a perfectly artificial imposition of numbers. I mean after all, having a Fibonacci series that works like that on a little diagram like this seems in itself kind of nonsense. Yet it seems to produce a very striking result. This is the only way that I can explain it…. Well, there are several things that I can say about this from my point of view. And that is that when you start revolving all these various systems you get to a thing like that [writes on chalk board] which was actually on the…. If this is done over a sixteenth note going rather fast, the next note is a sixteenth note with p on it or something like that, this is really very hard to perform indeed! If you have to swell from pp to f like that [Carter snaps his fingers], and then out. I mean this is impossible to perform. This is what happens all the time through this piece. So that, in a way, they can’t perform the piece exactly; it can’t be performed as it’s written. (Did you take that out? Will you put it back in again and I’ll show you the examples of this.) I mean, by the very nature of this series he’s putting them [the performers] into impossible positions. Now, it’s obvious that the piece somehow is composed and comes out in spite of the fact that some of these things are impossible to produce. Well here’s the one, right here. Right there (if you can get that clear, right over my finger). See there [m. 114, Soprano 1], there is a sixteenth rest, eighth note, sixteenth, and a quarter. On the eighth note there’s [a crescendo] from ppp to f, then on the sixteenth note is f, and then on the quarter note there’s a mf. That’s very hard. Here is one [m. 114, Contralto 1] that does the opposite: f for a sixteenth note, and then for two sixteenths f down to ppp, and then pp here. I mean this is nearly impossible. It would be impossible to train singers…. It’s remarkable that singers can…. This is a chorus, I mean, with all these irregular rhythms, with quintuplets. To have them sing as closely together as they do in this record is remarkable. You know, to have five or six people on a part, playing these things which never mark time in any way that’s clear, where [notes are] always off the beat or in some peculiar place in the measure, is remarkable as a piece of performance. But there are obviously certain things that are on the verge of unplayability in terms of speed. It probably would be impossible to teach any kind of a performer to get from…. (Excuse me, there’s… mosquitos in here.) It would be [slaps mosquito] impossible to get any performer to go very rapidly from a very low degree to a very high degree of dynamics on one note quickly, [that is] only sounded for a very, very brief moment. You can’t go “whock,” like that. It would be impossible to have time to do that. It is almost beyond physical capacities, also it would almost be impossible to hear it even it if were. Obviously, you could do it on an electronic machine, but how quickly one can perceive this kind of thing is very doubtful. It’s very hard to know. But this is one of the problems of this particular kind of a piece. In spite of that, obviously, Nono has written something which is very dramatic, and carries, although many details of this are not sung. They don’t really do the dynamics the way they are written here, at all, hardly at all on this performance. They are very much more quiet than that, I mean they are all much more even – it is all more-or-less mf or f with hardly any ppp singing in the chorus.

[ 15 ] [Audience member:] If it seems to be true, that this is successful, perhaps, not because of the system but in spite of it.

[ 16 ] I think so, yes.

[ 17 ] [Audience member:] Perhaps… It makes me think that there may be some almost secret aspect inside of this technique that we are not even talking about.

[ 18 ] Oh, I think there is! That is not secret in any way. Well, it’s just a composer’s secret, which is that they know how to write music. And make something out of this. I don’t know why he felt committed to do this. He [Nono] was very much involved with the people at Darmstadt and in particular with Messiaen, who was the man who invented this kind of music about 1949 – this idea of aleatoric… I mean of total serialization and of constant shifting and alternation of different dynamics on notes.

[ 19 ] [Audience member:] Do any movements have a feeling of greater tempo?

[ 20 ] No, that is another problem in this [piece]. It’s very hard to… If you are committed to include quite a large range of different note values in rather quick succession, it’s very hard to have many fast notes, because the majority of notes are going to be slow. I mean, there is not a large repertory of fast notes possible if they are single notes. I mean one septuplet can’t be played after one quintuplet. A performer wouldn’t be able to play it. Maybe two could, but I am not sure that they could distinguish it clearly. So, on the whole, the fast notes in this [piece] are sixteenths, quintuplets of sixteenths, and triplets, and then it grades down. There are many more [values totaling] thirteen quarter notes, eighth notes, or triplets, or quintuplets, [which] are going to sound slow, and anything above number three is going to sound like slow music. So this music always sounds slowly – it is impossible to write fast music with it. Slow and rather jerky, which, in my opinion, can be used to enormous effect at times. It’s just a type of thing, but it works out sometimes very, very effectively. Because it’s very effective in writing kind of bursts of sound, sort of explosions of things. Or you can have a lot of different rhythms contrasting very quickly with each another, a lot of different values, a lot of different attacks of notes. But it seems like now almost as if it were an artificial imposition which has no great reality. It doesn’t add to the form of the piece. And as I see it, anyhow, what he’s really doing is as if he were taking strips of notes, of sounds of notes, and pasting them together to make a piece. And he has these prefabricated little note-lengths, and what isn’t determined, of course, at all, is what the rests are. So therefore, it means that he could have shifted that note over here or this one here. So that while the order of notes is pretty much always the order of the twelve-tone row – F♯ is presumably followed by a C♯, and then F and then D – the amount of wait that you can have between each one of these notes is entirely free. Which means that in the end, the composition is just as free as almost any other composition migth be, except that you have these little items that you have to fit together like a mosaic in a floor. But on first sight, it sounds as if it were completely and strictly controlled. And I think that on the whole, any serialized music of this sort will only work where there is one element, one aspect of genuine freedom that the composer can control and work with. And in this [piece], as I say, it is the spaces between the notes that give it all the freedom. And also, the harmonic tension can be produced by that – you can fix it so that the certain notes will clash with other notes by spacing them in certain ways, and making many chordal sounds, many notes being held together [as] only one. And that can be controlled by putting the rests between them.

[ 21 ] [Audience member:] Does Nono apply the method of serialization to the text?

[ 22 ] Well, the text, yes of course… I don’t think the text… The text has nothing to do with the mathematical story. A text of this almost unbearably tragic quality in itself makes you read things…. Now this has not been about this kind of a subject. It is also possible that one wouldn’t feel quite the same way about it. Because it gives you also the impression of a kind of shredded musical language, which would seem symbolic of the text itself, as I hear it. That’s part of what’s moving about this particular piece. It may be, perhaps, even unmusical. But one hears it as something that’s so… as if music had just somehow fallen to pieces. And this is very moving, especially when you hear a large amount of it. It’s as if it was all full of, kind of broken things. So that the text helps you interpret a human thing, into something which may not be as human as all that. Although it was certainly… It’s obvious from the way he set the text – and the way the syllables have been placed – that he really intended you to hear it that way. I don’t remember what the text is for this particular one. What is it? I’m never sure whether I can understand Italian or not. Yes, well it starts out saying, “I’m dying” (“muoio”). (I don’t know where my glasses are. Not these….) Yes, “I’m dying for a world, which will become splendid in the future…. And the light…” And let me say that Luigi Nono was one of the first composers to set text…. The reason why I can’t read it from the music is that the soprano will sing one syllable and the bass will sing the next syllable of the word. And the text wanders around like that all over the score. So that in this case, the soprano sings “muo-” and then the bass answers with “-io,” and you’re supposed to realize that that’s “muoio.” “I am dying for a world that will shine with a light that is so beautiful and with such beauty,” and so forth. That’s the text of this particular piece [movement].

[ 23 ] [Audience member:] What is Nono doing now that you can’t understand?

[ 24 ] Well, it’s gotten very much more primitive than this. I haven’t… He’s also written quite a lot of electronic music in past years, some of which was very good, but then in recent times it’s become much less interesting. He’s writing an opera right at the moment, I don’t know what it is.

[ 25 ] [Audience member:] Intolleranza?

[ 26 ] Oh, Intolleranza, they did that in… yes I saw that. I saw it in Venice too. Yes, well that was very striking, I thought. But his music has become much more primitive in sound, not so subtle and curious as this piece is. Much more…. Much easier to do for one thing. I mean, it’s written in just big heavy blocks. Even Intolleranza is like that, which one would expect, let me say, from an opera. It’s very much simplified. And it seems to me that it also looses a good deal of its force by the fact that it’s less interesting to hear. So with this music is lost all melodic and all intervallic interest at all. It’s all just a series of spots of sound. And it does make a difference what the sounds are, somehow, and how they are spaced. It’s rather hard to know why they’re good when they are good, and why they are not when pieces like this…. I must say, I have no judgment about…. This particular piece, as I say, I like it. I have packs of other pieces you can hear. I have a work, for instance, that’s right before this on the tape – you can play a bit of that if you want – that is one of his more recent works, that’s called Diario Polacco (Polish Diary). (You can just… well you can just stop… stop before 260) This was a work that I heard…. He rewrote it since the version I have here, for the Warsaw Festival. It was written for the Warsaw Festival. It’s so bombastic that it seems kind of silly, but it’s very remarkable, just the same. (You can play some if you want to hear…. [music plays] I don’t know whether you’re in this or the other. It sounds like Il canto sospeso. It’s always a little bit alike. [music plays] Yeah, that’s it.) The problem is that the music itself doesn’t identify itself. I mean, the fact that it’s hard to tell which piece you’re playing is also a curious thing in itself, because it’s always very much the same. [music plays] (I think we’re still in the other one. Do you mind? I’m sorry I don’t want to bother the class. But let’s go back about an inch.) But the problem of a number of the post-war European composers is that there was a terrific excitement in the first ten or fifteen years after the war, and then, in the case of both Boulez and Stockhausen – and Nono – there was a deterioration. [music plays] Sorry, I don’t see the bombastic part that I remember in this now. (Well you can go back to the beginning if you want, but in any case I don’t want to keep the class waiting to find a place on the tape.) In any case, it proves partly a point. And that is that these pieces, in some way don’t have any sense of shape, that there are remarkable moments in them, and they are also almost much alike in character. (I don’t think this starts at the beginning of the reel, I’m not sure. Go ahead, see what happens.) [music plays] There’s always the same technique of little spots of sound that sort of sneak in and out in different…. [music continues] This piece has… [music continues] Well, anyhow you get the idea. I don’t want to play much of this.

[ 27 ] In any case, this is an entire tape of Nono’s music that I took off the Italian radio. Let me say that an American living in a foreign country, like Italy as I have a number of times, you come with a tape recorder and get the entire repertory of music, all modern pieces. You just turn on the tape recorder. Every night, or twice a week they have modern music concerts over the RAIN in Rome, and you just turn on a tape recorder. I have something like twenty-five tapes of pieces that I have never heard at all in the United States, some of them very interesting to me. But in any case, it’s a very strange kind of a thing to be able to do that when we seldom hear this kind of thing in the United States.

[ 28 ] [Audience member:] The music was interrupting a thought you had about Boulez and Stockhausen [inaudible]

[ 29 ] Well, what bothered me was that these people both seemed to have not found any future for themselves. They came to a certain point and wrote some very interesting works and then there seems to have been very little that they have been able to do in the last three, four, five years.

[ 30 ] [Audience member:] Right, so Boulez has stopped now, he’s conducting?

[ 31 ] He’s largely conducting, yes. His friends and students are all very disturbed that he doesn’t compose at all anymore. I’m not saying that he stopped completely, I don’t know that. I talked to him last year about this and he said that he had bought a house somewhere and that he was hoping to go to the country six months out of the year and compose, but still, he has decided to be a conductor and to make a living and a career as a conductor and this is very hard to do and be a composer at the same time.

[ 32 ] [Audience member:] Mahler?

[ 33 ] Yes – well, Mahler was remarkable. I don't know how he did it. With all those big symphonies too, when you think of it!

Footnotes

* I would like to thank Felix Meyer (Director of the Paul Sacher Stiftung) and Angela Ida De Benedicts (Scholarly Staff, Department Member at the PSS) for their support and invaluable insights about the works and lives of Elliott Carter and Luigi Nono. Also, I would like to thank the Amphion Foundation for permission to publish Carter’s lecture. Lastly, many thanks to Erin George, the Research Services Archivist at the University of Minnesota Archives, for providing me with the archival materials pertaining to Elliott Carter’s 1967 residency at the University of Minnesota.

1. University of Minnesota Historical Newspaper Collection, Minneapolis Tribune, Sun., June 25, 1967.

2. Carter’s Second String Quartet (1959) was performed by the Juilliard String Quartet on September 15, 1960, and Nono’s Il canto sospeso was performed on September 17, 1960. I would like to thank Angela Ida De Benedictis for providing me with the information regarding the XXIII Festival of Contemporary Music of the Venice Biennale Festival (1960).

3. A draft of Carter’s radio lecture on Schoenberg’s Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31 is published in Meyer and Shreffler 2008, 141-47.

4. For instance, see Schmidt 2012, 183-84, and Emmery 2017.

5. Also see Carter’s letter to William Glock, dated May 3, 1957, in which Carter expresses surprise and seems reluctant to accept Glock’s invitation to give a detailed analysis of Schoenberg’s Variations, Op. 31 at the 1957 Dartington Summer School festival. Carter avers that his understanding of Schoenberg’s technique is rather general, and notes that the talk he gave on Schoenberg on a previous occasion in 1957 for the CBC Vancouver radio station was “one for lay listeners and explained rather simply the devices Schoenberg used in that work” (Meyer and Shreffler 2008, 148-49; 140). Ultimately, Carter gave a lecture on Schoenberg’s Variations, Op. 31 and Stravinsky’s Agon (Meyer and Shreffler 2008, 147).

6. Reginald Smith Brindle, “Current Chronicle: Italy,” The Musical Quarterly 47, no. 2 (April 1961): 247-255.

7. Bailey (1992, p. 291) corrects the error. Bailey argues that Smith Brindle applied Nono’s general system of dynamics to his analysis of the second movement, without discerning the specifics of the method as it is applied throughout the movement. She goes even further in making a scathing comment regarding Smith Brindle’s entire analysis of the piece, nothing that “Not only has [Smith Brindle] made assertions about the whole work on the basis of his analysis of a single movement; it now becomes clear that his remarks about that movement are based on his analysis of the first two bars” (pp. 290-91).

8. Smith Brindle, 254. For details on how the order of the dynamic indications is determined through rotations in the second movement of Nono’s Il canto sospeso, see Bailey pp. 291-93.

9. See Guberman, 2012, 116-122; 129-30.

10. Il canto sospeso was composed in 1955–56 and premiered in Cologne on Oct 24, 1956, by the Kölner Rundfunkchor and the Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonie-Orchester, conducted by Hermann Scherchen.

11. See "Introduction" above, §6.

12. The correct duration of the F♯ in m. 108 is thirteen sixteenths. In his haste, Carter may have counted the quarter note in m. 108 and the half note in m. 109 as six eighth notes, then added the sixteenth in m. 108 to get a total of seven sixteenths without first doubling the number of eighth notes. [eds.]

Archival Collections

Elliott Carter Sammlung. Paul Sacher Stiftung, Basel, Switzerland.

Fondazione Archivio Luigi Nono, Venezia, Italy.

University of Minnesota Historical Newspaper Collection, Minneapolis, MN.

University of Minnesota Libraries Digital Conservancy, Minneapolis, MN.

Works Cited

Bailey, Kathryn. 1992. “‘Work in Progress’: Analysing Nono’s Il canto sospeso.” Music Analysis 11, nos. 2–3 (July–October): 279–334.

Bernard, Jonathan. 1990. “An Interview with Elliott Carter.” Perspectives of New Music 28, no. 2 (Summer): 180-214.

Carter, Elliott. 1965/94. “La Musique sérielle aujourd’hui (1965/94).” In Collected Essays and Lectures, 1937-1995, ed. Jonathan W. Bernard (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 1997), 17-18.

________. 1960. “Shop Talk by an American Composer.” The Musical Quarterly 46, no. 2 (Apr): 189-201. Reprinted in Collected Essays and Lectures, 1937-1995, ed. Jonathan Bernard (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 1997), 214-24.

________. 1946. “Walter Piston (1946).” In Collected Essays and Lectures, 1937-1995, ed. Jonathan W. Bernard (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 1997), 158-175.

Emmery, Laura. 2017. “Formation of a New Harmonic Language in Elliott Carter’s String Quartet No. 2.” Contemporary Music Review 36, no. 5 (October): 338-405.

Guberman, Daniel A. 2012. “Composing Freedom: Elliott Carter’s ‘Self-Reinvention’ and the Early Cold War.” Ph.D. diss. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

________. 2015. “Elliott Carter as (Anti-)Serial Composer.” American Music 33, no. 1 (Spring): 68-88.

Krenek, Ernst. 1940. Studies in Counterpoint Based on the Twelve-tone Technique. New York: Schirmer.

Leibowitz, René. 1949. Introduction à la musique de douze sons: Les Variations pour orchestre op. 31, d’Arnold Schoenberg. Paris: L’Arche.

Meyer, Felix. 2012. “Left by the wayside: Elliott Carter’s unfinished Sonatina for Oboe and Harpsichord.” In Elliott Carter Studies, ed. Marguerite Boland and John Link (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 217-35.

Meyer, Felix and Anne C. Shreffler. 2008. Elliott Carter: A Centennial Portrait in Letters and Documents. Suffolk: The Boydell Press.

Mila, Massimo. 1975. “Nonos Weg – zum Canto sospeso.” In Luigi Nono: Texte: Studien zu seiner Musik, ed. Jürg Stenzl (Zurich: Atlantis), 380–93.

Nielinger-Vakil, Carola. 2016. Luigi Nono: A Composer in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

________. 2006. “‘The Song Unsung’: Luigi Nono’s Il canto sospeso.” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 131, no. 1: 83-150.

Nono, Luigi. 1956. Il canto sospeso [score]. Mainz: Ars Viva Verlag.

Rufer, Joseph. 1954. Composition With Twelve Notes Related Only to One Another. Trans. Humphrey Searle. New York: Macmillian.

Schmidt, Dörte. 2012. “’I try to write music that will appeal to an intelligent listener’s ear.’ On Elliott Carter’s String Quartets.” In Elliott Carter Studies, ed. Marguerite Boland and John Link (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 168-89.

Smith Brindle, Reginald. 1961. “Current Chronicle: Italy.” The Musical Quarterly 47, no. 2 (April): 247-255.

Soderberg, Stephen. 2012. “At the edge of creation: Elliott Carter’s sketches in the Library of Congress.” In Elliott Carter Studies, eds. Marguerite Boland and John Link (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 236-49.