Fancy and Diligence: Carter’s “Notation of Polyrhythms” in his Piano Concerto

Gregor Herzfeld

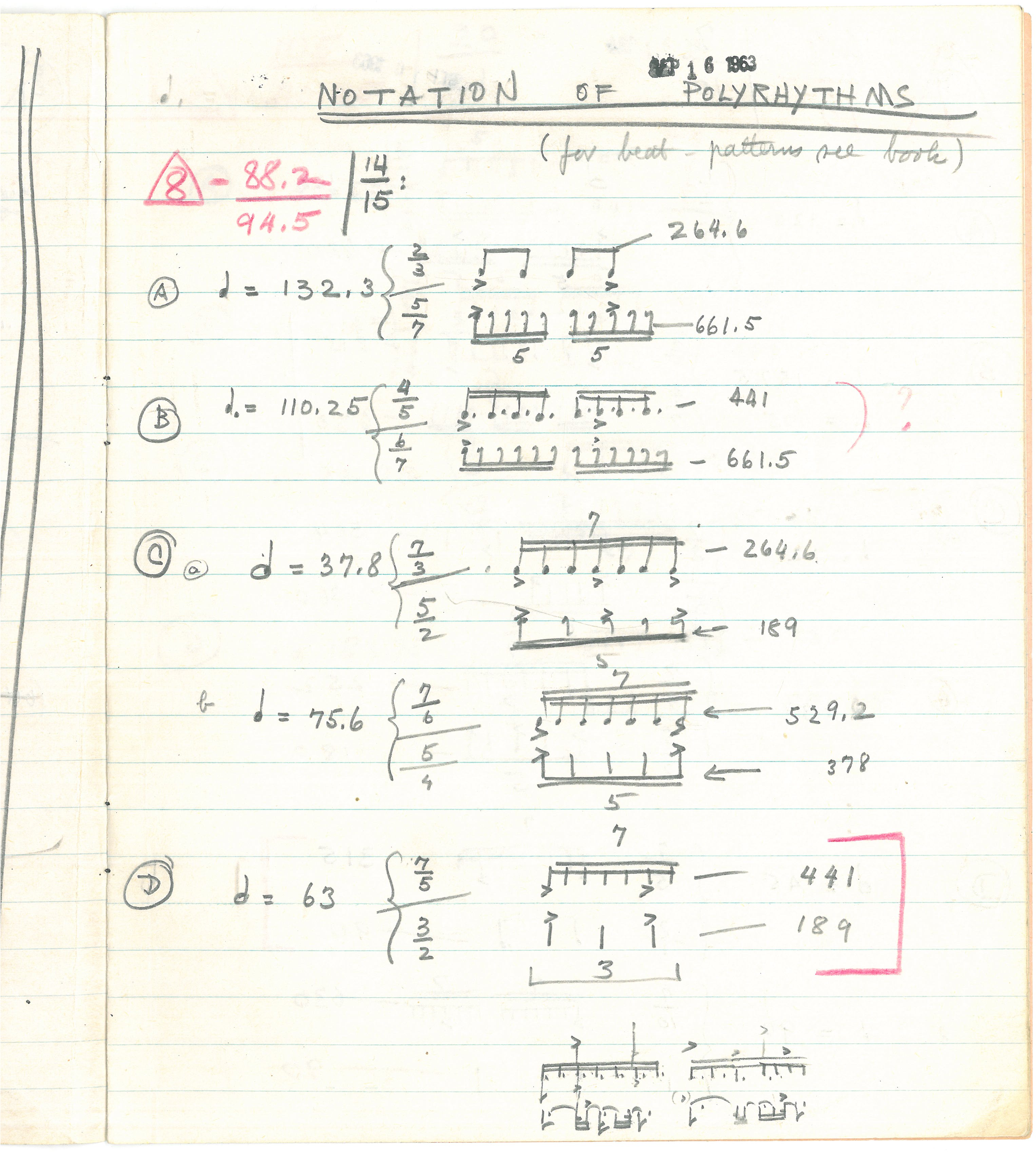

Elliott Carter, “Notation of Polyrhythms,” Piano Concerto sketches

Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation. Used by permission.

[ 1 ] Elliott Carter’s music gives the impression of being sublime. Especially his large orchestral scores from the 1960s and ’70s make the listener feel overwhelmed by the quantity and complex qualities of sound. Readers of his scores tend to be overwhelmed by the blizzard of notes, their meticulous elaboration, and – as everyone who has analysed this music knows – the high degree of organization. As a composer, Carter can be located on a line with Edgard Varèse, who defined music as the organization of sound, and with the serialists on both sides of the Atlantic, who explored tone and sound as their “material,” with qualities called “parameters,” in a way comparable to the natural sciences. The spirit of the musical avant-garde during Carter’s formative years in the 1940s and ’50s – characterized by Hermann Danuser as a “progress-oriented conception of composing analogous to science” driven by “an insatiable aspiration after rationality”(1)Hermann Danuser, Die Musik des 20. Jahrhunderts (Neues Handbuch der Musikwissenschaft, Vol. 7), Laaber 1984, pp. 295-296. – left its mark on Carter and influenced the way he approached, planned, and realized his compositions. The huge number of sketches, the literal “paper mountain” of notes, trials, and efforts(2)See David Schiff, “A Paper Mountain: Elliott Carter’s Sketches,” in Settling New Scores: Music Manuscripts from the Paul Sacher Foundation, ed. Felix Meyer (Mainz: Schott, 1998), pp. 115-18. – in the case of some pieces such as the Piano Concerto the number of pages approaches 10,000 – show Carter as a composer who experiments with all the combinatorial possibilities the somewhat limited reservoir of twelve pitch classes can offer him. Yet his music is at least as much the result of invention and fancy as it is diligence and discipline.

[ 2 ] A glance at these sketches – a glance into his artistic workshop – leaves us with an ambivalent feeling of fascination and trepidation – which again is a feature of the sublime: fascination with the glimpse into the workings of his mind; trepidation about all the things that are hard, or even impossible to understand, since it is not always clear or possible to reconstruct how a sketch of numbers, notes, lines, and circles – all in different colors – finds its way into the finished score. And even after one has spent several hours discovering the meaning of a sketch in a technical sense, the question remains: What is the point of this insight? To what end does one attempt to solve all the riddles hidden in the composer’s workshop?

[ 3 ] Let us for this album leaf set aside doubt and trepidation, and approach with confidence something that we can grasp with greater ease: a page from the sketches of the Piano Concerto (which Carter began in 1962 after he had finished the Double Concerto, and completed in 1965). The piece is dedicated to Igor Stravinsky for his 85th birthday, and was premiered on January 6, 1967, by Jacob Lateiner and the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Erich Leinsdorf. The sketch page reproduced here is archived in the Elliott Carter Collection at the Paul Sacher Stiftung in Basel, together with a large folder of sketches related to this piece. It is dated September 16th 1963, which makes it a draft from a rather early stage.

[ 4 ] A close look at the sequence of sketches reveals that Carter started with very preliminary ideas concerning the general process of the piece. In this regard, he also made notes about other piano concertos from the 19th and 20th centuries, by Franck, Saint-Saëns, Bartók, Prokofiev, Shostakovitch, and of course Stravinsky. The second step was to figure out the general features (intervals, tempi, modes of expression) of each instrumental layer (soloist, concertino, and orchestra) according to characteristics he had found in his classic models. The next stage was to find corresponding trichords and assign them particular tempi. In this stage he explored the full repertoire of possible combinations of intervals, tempi, and rhythms, for each layer individually and in groups of two, three, four, etc. Carter made “inventory” sketches for each one, perhaps playing on the words “invention” and “category.” After having done this work, he went on to sketch specific musical gestures, some of which made their way into the completed piece.

[ 5 ] The sketch page above is an essay in the “Notation of Polyrhythms” for the pitch content of Carter’s trichord 8 (026).(3)See Elliott Carter, Harmony Book, ed. Nicholas Hopkins and John F. Link (New York: Carl Fischer, 2002), p. 23. As we know from Carter’s chart of the distribution of intervals, trichords, and metronomic speeds,(4)Reprinted in Elliott Carter, Collected Essays and Lectures, 1937-1995, ed. Jonathan W. Bernard (University of Rochester Press, 1997), p. 249. trichord 8 belongs to the orchestra, and is linked to two metronomic speeds, 88.2 and 94.5. Carter writes his symbol for trichord 8 in red pencil (the number 8 enclosed in a triangle), along with the two speeds, which he arranges as a fraction making the ratio 14:15 (88.2 = 14x6.3, 94.5 = 15x6.3). He then explores how to notate these two speeds in the context of various notated tempi. Letter (A) shows that at a notated tempo of  = 132.3 ( = 21x6.3), 88.2 is 2/3, and 94.5 is 5/7 of it. Translated into rhythmic notation the slower 88.2 is realized by accents every three eighth notes, while the slightly faster 94.5 can be realized by accents every seven quintuplet sixteenths. Under (B) Carter explores the notation of the same speeds at a notated tempo

= 132.3 ( = 21x6.3), 88.2 is 2/3, and 94.5 is 5/7 of it. Translated into rhythmic notation the slower 88.2 is realized by accents every three eighth notes, while the slightly faster 94.5 can be realized by accents every seven quintuplet sixteenths. Under (B) Carter explores the notation of the same speeds at a notated tempo  = 110.25 (a speed that is also assigned to trichord 2). Under (C) the notated tempo is

= 110.25 (a speed that is also assigned to trichord 2). Under (C) the notated tempo is  = 37.8 (or

= 37.8 (or  = 75.6), and so on.

= 75.6), and so on.

[ 6 ] On the following pages Carter goes through the same exercise for trichords 9, 2, 6, 7, 1, and 10. On the page for trichord 7,(5)Sketch number 235-0602. for example, we encounter under (C) – at a notated tempo of  = 48 – the polyrhythm well-known from the very beginning of the concerto.

= 48 – the polyrhythm well-known from the very beginning of the concerto.

[ 7 ] When analysing the score of the Piano Concerto the sketches will be extremely useful. They help to identify the sections in which the pitch or interval content of the trichords is realized at the allocated metronomic speed, regardless of the notated tempo. And to what end? Maybe a complete analysis informed by the composition sketches is not the final aim of a musicologist’s work, but it may (should?) serve as a starting point for developing an interpretation. It helps us to understand how the composer understood, conceived, and carried out a composition, which is an important element in forming a narrative of music history.

Footnotes

1. Hermann Danuser, Die Musik des 20. Jahrhunderts (Neues Handbuch der Musikwissenschaft, Vol. 7), Laaber 1984, pp. 295-296.

2. See David Schiff, “A Paper Mountain: Elliott Carter’s Sketches,” in Settling New Scores: Music Manuscripts from the Paul Sacher Foundation, ed. Felix Meyer (Mainz: Schott, 1998), pp. 115-18.

3. See Elliott Carter, Harmony Book, ed. Nicholas Hopkins and John F. Link (New York: Carl Fischer, 2002), p. 23.

4. Reprinted in Elliott Carter, Collected Essays and Lectures, 1937-1995, ed. Jonathan W. Bernard (University of Rochester Press, 1997), p. 249.