“... no patience anymore for longer pieces”: A Look at Two Late Miniatures by Elliott Carter*

Felix Meyer

* This article was first published in German as »... keine Geduld mehr für längere Sachen«. Ein Blick auf zwei späte Miniaturen von Elliott Carter, in Ereignis und Exegese: Musikalische Interpretation, Interpretation der Musik (Schliengen: Edition Argus, 2011), pp. 769-82. [Eds.]

[ 1 ] In the course of music history, there have always been composers who have remained active at an advanced age. But the case of Elliott Carter is probably unique: not only did this composer, born in New York City in 1908, retain his creative powers until well past his one-hundredth birthday, he almost spectacularly enhanced his productivity in old age, having completed only a handful of scores in the 1950s and 1960s. The 1990s and 2000s witnessed some eighty new works from his pen, meaning that Carter finished more than half of his roughly one-hundred-fifty acknowledged works after his eightieth birthday. Even more impressive than the sheer volume of his late work is its variety: the spectrum ranges from aphoristic solo pieces to large-scale orchestral works, from playful pièces d’occasion to deeply-felt settings of demanding poetry. Moreover, Carter not only continued to cultivate the genres dear to him from the very beginning (e.g. the string quartet), he also turned to genres into which he had never ventured at all, or had long neglected. We need only recall his first and only opera, What Next? (1997-98), and his return, after a sixty-year hiatus, to a cappella vocal writing with his setting of John Ashbery’s Mad Regales (2007).

[ 2 ] It is no easy matter to find one’s way through the extremely rich and multifarious music of Carter’s old age. It is even difficult to define the point at which his late period began. In any event, there is no clear turning-point in his later years to match his earlier transition, undergone in the late 1940s and early 50s, from a broadly conceived neo-classicism at the outset of his career to a tonally and rhythmically expanded idiom based on the opposition and superposition of contrasting musical layers. On the contrary, his path from the middle and late 1950s is noteworthy precisely for its remarkable continuity and linearity. Still, it is possible to descry a few general trends that gradually altered the character of his music from the 1980s on. One of them is an effort to achieve greater textural translucence (often accompanied by an expressly informal and relaxed musical inflection). Another is the development of a formal approach based on concatenation rather than superposition and layering. Not least, we also find a more conciliatory treatment of the instrumental collective, which Carter increasingly treated as a single large sonic resource rather than radically splitting it into heterogeneous opposing sub-ensembles, as in his earlier work.(1)See above all David Schiff’s introduction to the new edition of his The Music of Elliott Carter (London: Faber and Faber, 1998), pp. 1−31, esp. pp. 29−31, and John Link, “Elliott Carter’s Late Music?,” in the progam booklet of the Tanglewood Contemporary Music Festival, July 20-24, 2008, pp. 79−81. But it was above all after the start of the new millennium that Carter, declaring that he had “no patience anymore for longer pieces,”(2)“Musik kann uns gefährlich werden” (Elliott Carter im Gespräch mit Christine Lemke-Matwey), Der Tagesspiegel (Berlin, April 20, 2009); quoted from the on-line version at http://www.tagesspiegel.de (accessed on November 16, 2010). tended to concentrate on fairly short works, often for small combinations of instruments. Here two further features suggest that the terms “late work” and “late style” apply at least to this most recent creative period. First, we note a certain simplification in his compositional approach, resulting from, among other things, the fact that he began to avoid the all-embracing, highly elaborate rhythmic and harmonic structural schemata he had often relied on in the past. Secondly, Carter increasingly sought recourse in the artistic legacy of early American modernism, which had left a deep impression on him in the 1920s and 1930s only to be “overlaid” by his later interest in the developments of the international avant-garde.

[ 3 ] These characteristics are fully in line with the complex of features that Theodor W. Adorno (for Beethoven) and Edward Said (for various musicians and poets) elaborated in their reflections on “late style” in artistic creation.(3)Theodor W. Adorno, “Spätstil Beethovens” (1937), in idem, Musikalische Schriften IV, Gesammelte Schriften 17, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1982), pp. 13–17; Edward Said, On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain (New York: Pantheon Books, 2006). And in Carter’s case, as with other artists, they not only reflect a particular evolutionary stage in his career, but are also rooted in biographical factors, such as the impact of illnesses or the age-related decline of his physical strength. There was most likely a connection between the relatively “small scale” of his recent works (i.e. his inclination to think in terms of “snapshots” rather than complex wholes)(4)One indication of this is the fact that in his final years Carter, in sharp contrast to his earlier practice, once extracted a section from an existing score (ASKO Concerto, 1999−2000) and turned it into an independent work (Retracing). Conversely, he also integrated two finished compositions (Shard, 1997, and Call, 2003) in toto into large-scale new works (Luimen, 1997, and Réflexions, 2004). and the fact that he gradually had to shorten his working periods as he grew older. But there was probably also a connection between the spare, translucent fabric of this music and the partial loss of hearing he suffered during his severe health crisis of the early 1990s – a connection of the sort that scholars explore in so-called “disability studies.”(5)See the discussions and bibliography in Joseph N. Straus, “Disability and ‘Late Style’ in Music,” The Journal of Musicology 25, no. 1 (winter 2008), pp. 3−45.

[ 4 ] Nevertheless, the discussion below will not focus on such general aspects, but rather on the extent to which the above-mentioned late-period tendencies specifically left a mark on two selected miniatures from Carter’s pen: the song “Re-statement of Romance” from his Wallace Stevens cycle In the Distances of Sleep (2006), and the string composition Sound Fields (2007). My selection fell on these two pieces not least because the reductive impulse and the reversion to early American modernism are especially apparent in them, and because they thereby strikingly contradict the standard image of Carter as a eurocentric composer staunchly committed to complexity.

“Re-statement of Romance” (from In the Distances of Sleep)

[ 5 ] Throughout his life, Carter had an especially close affinity with literature. Indeed, while a student at Harvard College (1926-32), he initially majored in English literature before turning entirely to music. It therefore comes as no surprise that he wrote a great many vocal and especially choral works in his early years, including some based on poems by Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, Hart Crane, Mark Van Doren, and Allen Tate. However, after completing his choral work Emblems (1946-47), based on a text by Tate, he comprehensively renewed his musical language and entered a long period in which he focused exclusively on instrumental music. One reason for this was undoubtedly his disappointment at the poor quality of most performances and the widespread conservatism he encountered in singers, and still more in the existing non-professional choral societies. It was not until the mid-1970s that Carter, encouraged by the soprano Susan Davenny Wyner and aware of the emergence of a young generation of performers specializing in contemporary music and fully capable of meeting its demands, again ventured to compose a vocal work: the song cycle A Mirror in Which to Dwell on poems by Elizabeth Bishop. In the years and decades that followed, he ultimately brought forth a large number of poetry settings, at first sporadically, but from the late 1990s with ever-increasing frequency. The great majority of them draw on American poets: William Carlos Williams, Wallace Stevens, John Ashbery, Ezra Pound, Louis Zukofsky, Marianne Moore, and T. S. Eliot.

[ 6 ] This list of poets makes it clear that Carter, in his late work (in the narrow sense of the term), delved more intensively than ever before into the classical authors of American modernism. In contrast, his vocal works from the 1970s to the 1990s (and some of his early works) tended to draw on the writings of living poets (including John Ashbery, Robert Lowell, and John Hollander in addition to the aforementioned Elizabeth Bishop), with whom he often maintained personal contact.(6)This also applies in particular to his opera What Next? of 1997–98, conceived jointly with Paul Griffiths. However, this product of a genuine collaboration with a writer represents a special case. In other words, his late music already demonstrates a certain element of “reversion” in his choice of texts – or, as Paul Griffiths put it, “Carter’s tour of his library is circular.”(7)Paul Griffiths, “‘Its full choir of echoes’: The Composer in His Library,” Elliott Carter: A Centennial Celebration, Festschrift Series 23, ed. Marc Ponthus and Susan Tang (Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2008), pp. 23−40, quote on p. 25. Yet his interest had expanded, and he turned to several poets whose writings, though long familiar to him, he had not set in his early years. This is especially remarkable in the case of Wallace Stevens (1879-1955), particularly since Carter’s artistic world-view bears such a striking affinity with Stevens’s that David Schiff, in his study The Music of Elliott Carter, did not hesitate to call the poet one of the composer’s “spiritual forebears” (another was Henry James).(8)Schiff, The Music of Elliott Carter (see note 1), pp. 2–8, quote on p. 4. Both artists shared, among other things, a belief in a radically subjective outlook in which the work of art, rather than reflecting reality, should be viewed as its abstract counterpart.(9)Recently expressed in Edward Ragg, Wallace Stevens and the Aesthetics of Abstraction (Cambridge University Press, 2010). In this sense, Stevens’s work turns quite centrally on the problem of how an elusive reality can be grasped and re-ordered in the medium of poetry. Similarly, Carter had always attached far greater importance to the internal logic of musical discourse than, for example, to references to pre-existing types of music. (For both composer and poet, this largely precluded any explicitly nationalistic “Americanism.”) But in other points, too, such as the idea of constant change (an idea of paramount importance in their respective oeuvres), there are commonalities suggesting a close aesthetic kinship.

[ 7 ] The immediate impetus for Carter’s late compositional engagement with Wallace Stevens came in the form of a commission from the Met Chamber Ensemble and James Levine. The commission ultimately led to his song cycle In the Distances of Sleep for mezzo-soprano and instrumental ensemble, from which we will take a closer look at No. 3, “Re-statement of Romance.” Particularly striking about this work, premièred in New York by the commissioning ensemble and the singer Michelle DeYoung on October 15, 2006, is a fact related to its genesis: Carter, although he did not actually start work on the piece until early 2006, had already given initial thought to it “around 2003.”(10)Elliott Carter, Program note for In the Distances of Sleep, printed in the program booklet for the premiere in New York’s Zankel Hall, Carnegie Hall, on October 15, 2006. A considerable length of time thus elapsed between his decision to write the piece and its actual composition. Carter seems to have used this time to carefully select the poems he wished to set. The selection process is documented in particular by two lists of poems that evidently caught his special attention. They reveal how Carter narrowed his original selection step by step from more than thirty titles. The second list (Example 1), containing eighteen titles and the corresponding page references to the poetry volume he consulted,(11)Wallace Stevens, Collected Poetry and Prose, ed. Joan Richardson (New York: Library of America, 1997). was eventually pared down with underlining and additional crosses to a still narrower selection of thirteen poems, and finally to eight. (Five of them, plus the unlisted poem “The Roaring Wind,” ultimately found their way into the finished work.) The selection process reveals that he increasingly focused his attention on texts dealing with aging and the passage of time. It is accordingly these themes, conveyed in images of autumn and especially of wind as an elemental force of change, that essentially dominate the poetic message of In the Distances of Sleep.

Example 1

List with poem titles from Wallace Stevens; sketch page (detail)

Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation

[ 8 ] However, it is not an image from nature that stands at the center of the work, but a poem of night and love: “Re-statement of Romance.” In this case “center” is meant in a wholly literal sense, for In the Distances of Sleep is conceived as a symmetric cyclical whole in which two long and thematically expansive songs, “Puella Parvula” (No. 1) and “God is Good. It is a Beautiful Night” (No. 6), form the outside framework while “Metamorphosis” (No. 2) and the two songs “The Wind Shifts” (No.4) and “The Roaring Wind” (No. 5), played attacca, constitute an internal bracket.

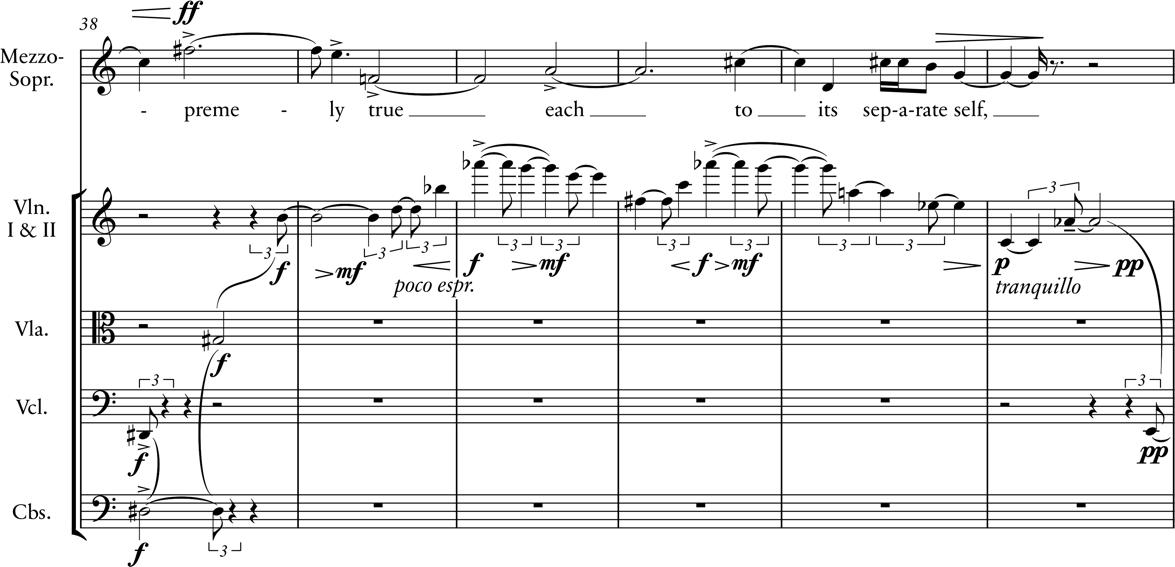

[ 9 ] Moreover, this internal bracket is underscored by symmetry in the instrumentation: the two outside songs employ the full contingent of woodwind, percussion, piano, and strings, whereas Nos. 2 and 4-5 entrust the instrumental part to a slightly smaller ensemble, and the central “Re- statement of Romance” (No. 3) is given entirely to muted strings playing a single melodic line that migrates from instrument to instrument in a sort of Klangfarbenmelodie (see Examples 2a, 2b, and 2c).

Example 2

Elliott Carter, "Re-statement of Romance" (from In the Distances of Sleep).

© Copyright 2006 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

a) mm. 1-8

b) vocal part, mm. 21-27

c) mm. 38-43

[ 10 ] The extreme reduction that Carter imposed on “Re-statement of Romance” by conceiving it as a bare two-voice texture for voice and strings finds its explanation in the underlying poem:(12)Ibid., p. 118.

[ 11 ] The subject of this poem of 1935 is thus the coming together of two lovers – or perhaps we should say the conditions governing such a coming together, as Stevens makes the seemingly paradoxical pronouncement that true closeness between individuals arises not from self-abnegation but rather from being “supremely true each to its separate self,” to quote the poem’s penultimate line. Carter created a fitting musical symbol for this subject by reducing the texture to two voices, each of which retains its own complementary identity while being related to the other. The poetic persona is emphasized by the vocal line, with its more active and dynamic rhythms, narrower ambitus (as befits the nature of the human voice), and strictly syllabic setting. The figure addressed in the second person singular is personified by the instrumental part, with its preponderance of long sustained notes, its shadowy dynamic level (lowered two or three degrees in comparison with the vocal part), and registral leaps bestriding the entire tonal space. To enhance the independence of the two voices, Carter based the song on a characteristic polyrhythm that rules out any rhythmic coincidence: the vocal part moves by and large in quarter-notes at 66 beats per minute, while the notes in the strings, especially in the first half and the ending, each have a duration of 7 2/3 quarter-notes (or 23 triplet eighths), thereby producing a metronomic tempo of roughly 8.6.

[ 12 ] Here, in response to the poem, Carter has created what might be called an “archetype” of a polyrhythmic compositional approach reduced to a skeletal two-voice texture. Just how formative this notion of two polyrhythmically offset voices was to the conception of “Re-statement of Romance” is revealed by the sketches. The very first attempt at a two-voice draft, written a semitone higher than in the final version, displays the aforementioned polyrhythmic relation between the voice and the instrumental part.(13)This sketch is reproduced in Felix Meyer and Anne C. Shreffler, Elliott Carter: A Centennial Portrait in Letters and Documents (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2008), p. 337. Moreover, the same sketch leaf already shows the opening of the vocal line rooted in two variants of the all-trichord hexachord, i.e. a six-note set containing each of the twelve trichords at least once.

[ 13 ] The poem deals not only with two individuals, but also with night. Here, however, rather than symbolizing seduction (as so often in romantic poetry), night represents a sphere inaccessible and alien to human beings. “Only we two are one, not you and night / Nor night and I, but you and I, alone”: thus alone also in the middle of the poem, lines 6 and 7, in almost overstated dissociation. In other words, the “I” and the “you” are contrasted with night as a third entity – a constellation that Carter took into account in his setting by stressing these three key concepts in a quite special manner. Again, he resorted to a device of maximum simplicity – one that he had already employed in A Mirror on Which to Dwell and elsewhere. As we can see in Example 2b, he assigned a specific pitch to each of these three concepts: G#4 (or Ab4) to “night,” G4 to “I,” and F5 to “you.” Moreover, he did so not only in this passage, but throughout the song. And at least in one case he also used the resulting semantic association in reverse order, anchoring the piece as it were in the semantic field of “night” by bridging all the larger rests in the vocal part with the pitch G# or Ab in the accompaniment from bar 13 on. This can be seen in the final measure of Example 2c.

[ 14 ] A description of this sort might convey the impression that “Re- statement of Romance” is an astutely calculated but more or less static piece of music. However, this is by no means the case: just as Stevens fashioned the poem linguistically from whole cloth (using, among other things, a syntactic escalation in which one- and two-line units culminate in a seven-line sentence), the music unfolds in a single large arc of tension climaxing at the line “Supremely true each to its separate self” by means of a stepwise increase in dynamics, a gentle expansion of the vocalist’s ambitus (the previous peak pitch F5 being surpassed by an F♯5 at the word “supreme”)(14)A similar expansion of the tonal space, both upward and downward, is also found in the final seven bars of the string part., and a multi-stage rhythmic acceleration in the strings. It is this last device which is especially important to Carter’s interpretation of the poem, for it causes the strings to move more quickly at the climax (mm. 38-41) than the sharply decelerated vocalist (see Example 2c). In other words, precisely at the words “Supremely true each to its separate self” (and only there) the two parts effect an “exchange.” Thus Carter, in the simplest yet most precise way imaginable, has lent expression to Stevens’s paradox: that two individuals can become as one only by remaining true to themselves.

Sound Fields (2007)

[ 15 ] An equally radical reduction of resources, though of a wholly different and complementary nature, is found in Sound Fields, a four-minute string piece composed in 2007 on a commission from the Tanglewood Music Center for a large-scale tribute to Carter during the 2008 Tanglewood Festival. (In the summer of 2008 Carter, at the request of Oliver Knussen, created a similarly structured pendant for twenty-four woodwind instruments entitled Wind Rose.) At its premiere on July 20, 2008, with the Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra conducted by Stefan Asbury, the piece occasioned great amazement, as its seeming repetitiveness and lack of development conjured up unexpected associations, e.g. with the music of Morton Feldman. Indeed, this was hardly a coincidence: just as many of Feldman’s works were inspired by the constructive principles of Abstract Expressionism, Carter drew on this same highly influential current of post-war American art in Sound Fields. As the title indicates, his reference point was “color field” painting, generally considered a major trend in Abstract Expressionism (along with “gestural” painting).(15)See e.g. Irving Sandler, "Abstrakter Expressionismus: Der Lärm des Verkehrs auf dem Weg zum Walden Pond," Amerikanische Kunst im 20. Jahrhundert: Malerei und Plastik, 1913−1993, ed. Christos M. Joachimides and Norman Rosenthal (Munich: Prestel, 1993), pp. 89−96 [catalogue of an exhibition held in the Martin Gropius Building, Berlin, May 8 – July 25, 1993]. Moreover, the commentary he prefaced to the printed edition shows that he took his bearings mainly from the work of Helen Frankenthaler,(16)“Composer’s Note” in Elliott Carter, Sound Fields for string orchestra (Hendon Music/ Boosey and Hawkes, 2007), n.p. that is, not on any particular painting, but on certain basic features of her total oeuvre. Born in 1928, Frankenthaler belongs to the second generation of Abstract Expressionists. Like Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, and Clyfford Still, in the 1950s and 1960s she worked with large swaths of color containing gentle modulations. But she declined to adopt their extreme geometric reductionism or their penchant for almost totally monochrome painting. By directly applying the paint to untreated canvas as early as 1950, she also brought into play a technical innovation that directly met the theoretical demand for two-dimensionality – an innovation soon taken up by other artists.(17)On Frankenthaler’s work see above all Alison Rowley, Helen Frankenthaler: Painting History, Writing Painting (London and New York: I. B. Tauris, 2007). The intensity of the impact of color is thus of signal importance in Frankenthaler’s work, though she never entirely banished the representational element from her paintings, least of all the associations with landscapes.

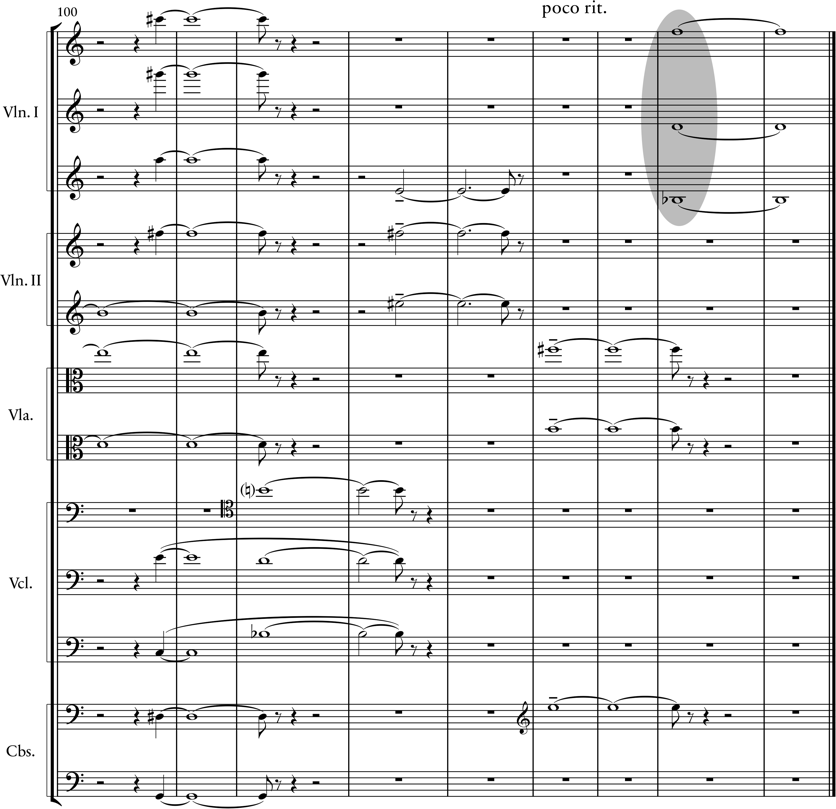

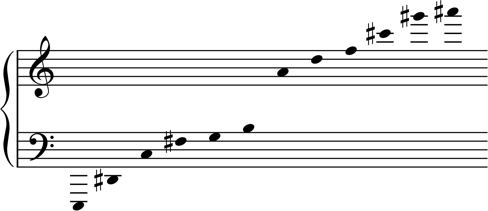

[ 16 ] The manner in which these painterly qualities are transferred to the medium of music becomes clear at the very opening of Sound Fields (see Example 3a). Here we already see that Carter has almost entirely dispensed with counterpoint, figuration, and rhythmic-melodic shapes, thereby taking a step that bears comparison with the suppression of the brushstroke or the rejection of gestural and physical expression in the works of the “color field” painters. Instead, harmony comes all the more noticeably to the fore: indeed, Sound Fields consists of nothing more than a slow series of soft chords, now separate, now intersecting, all at various levels of density, and all played mezzo piano and senza vibrato. The notes in these chords are fixed at the same pitch-level, and thus always sound in the same register. More than that, each chord in the opening section shown in Example 3a (and beyond) is a sub-chord derived from a single “mother chord” of a sort that Carter, in his later years, employed with increasing frequency. As shown in Example 4a, it is an “all-interval twelve-tone chord,” i.e. a twelve-tone chord extending over five-and-a-half octaves in which every interval, from minor 2nd to major 7th, occurs exactly once within the octave range. (The formula placed beneath the example expresses the series of intervals in the chord from bottom to top, with the digits and the letters T and E – for ten and eleven – referring to the number of half-steps in the intervals that make up the chord.) It is also one of the intervallically asymmetrical “Link” chords (named for the composer John Link) which, among other things, have the property of containing at least one variant of the all-trichord hexachord mentioned in connection with “Re-statement of Romance.”(18)See Link’s discussion in Elliott Carter, Harmony Book, ed. Nicolas Hopkins and John F. Link (New York: Carl Fischer, 2002), “Appendix 2: The ‘Link’ Chords,” pp. 358-61, esp. p. 358.

Example 3

Elliott Carter, Sound Fields

© Copyright 2007 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

a) mm. 1-8

b) mm. 100-108

Example 4a-b

All-interval twelve-tone chords in Sound Fields

a) 98T427613E5

b) E9614T53872

Example 5

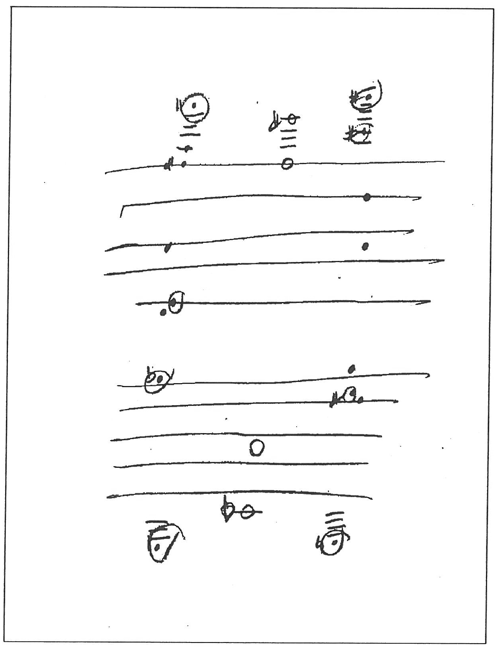

Basic harmonic structure of Sound Fields; sketch page

Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation

[ 17 ] Besides this basic chord, a second harmonic pillar is at work in Sound Fields. In bar 54, the exact midpoint of the 108-bar score, first two and then six further pitches change positions to form a different all-interval twelve- tone chord with the four unaltered remaining pitches (Example 4b). They are then restored, step by step, to their original register beginning in bar 73, i.e. at exactly three-quarters of the way through the piece. This description completely covers the piece’s harmonic “deep structure” but not its extraordinarily subtle and differentiated “sonic surface,” created by dissecting the original chord into constantly changing sub-chords. As we can see in Carter’s sketch leaf (Example 5), the surface consists solely of these two reference chords, and is thus so straightforward that we are justified in speaking of a “prime model” for Carter’s harmony similar to the (poly)rhythmic structure of “Re-statement of Romance.” In the sketch, the two all-interval twelve-tone chords, whose top notes A♯7 and C♯7 are interchanged compared to the final version, are represented as three sets of pitches: the eight pitches belonging solely to the first chord are shown at the left, the eight belonging solely to the second chord are shown at the right, while the four pitches common to both chords – the “intersection” – appear in the middle.

[ 18 ] To define the analogies between Sound Fields and painting more closely, we should go beyond the aforementioned basic impulse toward reduction and mention above all the analogy between sustained notes and color fields, both of which are outlined with clearly demarcated horizontal and vertical extents. The analogy is further supported by the familiar spatial metaphor of a sound-surface (Klangfläche). Indeed, the very title of the work suggests an obvious connection between color and sound (“color field” vs. “sound field”). Here, however, we soon encounter terminological difficulties. Does the familiar Klangfarbe metaphor relate primarily to the instrumental realization of the compositional fabric (as opposed to its substance), in which case the string sound is to be understood somewhat as a basic color that takes on different shades as the chords change? Or is it the twelve-note chords themselves, contrary to the standard metaphor, that should be viewed as colors and the smaller chords extracted from them as shades?

[ 19 ] As stimulating as it might be to pursue these questions, it ultimately distracts us from another equally important aspect: despite his adoption of certain constructive principles from the visual arts, Carter by no means entirely refrained from structuring the piece with genuinely musical resources, meaning in this case shaping it into a clearly structured temporal continuity in accordance with the autonomous laws of the musical medium. Like Arnold Schoenberg’s famous “chord-color piece” from the Five Orchestral Pieces, op. 16, Sound Fields has a gently adumbrated tripartite ABA’ form, with the B and A’ sections that make up the second half of the piece heavily abridged and temporally shifted. Moreover, the ending is prepared by having the previously seamless continuity of chord changes interrupted several times beginning in bar 86: first by a whole-bar general pause, then by four brief eighth-note rests. Finally Carter, in the very last two bars, made use of a sub-chord that occurs only once in the entire piece: a pure B-flat major triad (see Example 3b).

[ 20 ] This concluding triad is strangely ambivalent in effect: while its “tonal” associations set it apart from the preceding chords, it is structurally on a par with them, being likewise filtered out of the “mother chord.” To a certain extent it is also prepared in advance, for in the course of the piece we find again and again stacks of chords with heavily tonal components. Indeed, the composition essentially resides in the juxtaposition not only of contrasting chordal densities, but of contrasting degrees of dissonance. It is precisely in this respect that Sound Fields differs from the only other piece in Carter’s oeuvre that is likewise constructed from a single chord: the third piece of Eight Etudes and a Fantasy for wind quartet (1949-50), which deals with the changing instrumental garb of a D-major triad sustained without alteration for the duration of the piece. In Sound Fields, however, the contrasting sub- chords are spliced together into a subtly modulating continuum of musical tension.

— ◊ —

[ 21 ] It goes without saying that these two pieces throw only a tiny spotlight on Carter’s late music. They are nonetheless of special interest, for they illustrate, in magnified form, certain general trends manifest in that music. Both “Re-statement of Romance” and Sound Fields bear witness, with extreme clarity, to Carter’s fondness for focusing on narrowly circumscribed compositional problems, which he proceeds to illuminate with all the more sophistication. They also illustrate his reversion to two of his compositional “prime procedures”: the systematic polyrhythmic shift of voices (in “Re- statement of Romance”) and the use of reference chords to align the compositional fabric (in Sound Fields). In his early works, these two procedures usually occur in several musical sub-layers, and sometimes even between these sub-layers, making them very difficult to follow. This applies in particular to his works of the 1960s and 1970s, with their almost collage- like overlaps of two or more levels of musical procedures – overlaps which, however, are always calculated to the smallest detail. Later the picture changes, and we find a preference for a formal approach tending more toward concatenation, where the juxtaposition of contrasting textural layers is, so to speak, moved from the vertical plane to the horizontal.(19)Compare Jonathan W. Bernard’s distinction between “successive” and “simultaneous” textures in Carter’s music of the 1950s and ‘60s, in idem, “The Evolution of Elliott Carter's Rhythmic Practice.” Perspectives of New Music 26, no. 2 (1988): 164-203. This approach comes to a head in several new works in which ritornello-like sections are interpolated to produce something akin to a concerto grosso. (Examples include the ASKO Concerto of 1999-2000, the Boston Concerto of 2003, and Soundings of 2005.)(20)See Marguerite Boland, “Ritornello form in Carter’s Boston and ASKO concertos,” In Elliott Carter Studies (Cambridge University Press, 2012), 80-109. In pieces such as “Re-statement of Romance” and Sound Fields, however, the horizontal context is finally abandoned: here the two “prime models” of Carter’s compositional technique occur in isolation and sustain the full substance of the music.

[ 22 ] Besides the reductive impulse, “Re-statement of Romance” and Sound Fields also reveal a conspicuous reversion to early twentieth-century American modernism – a reversion which is in turn symptomatic of Carter’s late work. It is evident not only in his relation to the poetry of Wallace Stevens and the paintings of Helen Frankenthaler (neither of whom, incidentally, Carter knew personally), but equally in the compositional fabric. The polyrhythmic model of the song, for example, unmistakably points back to his efforts toward “dissonant counterpoint,” and particularly to its underlying principle of deliberate “sounding apart,” as formulated and practiced in the writings and works of Henry Cowell, Charles Seeger, Ruth Crawford Seeger, and other American “ultra-modernists” of the 1920s and early 1930s. Likewise, Carter follows in the footsteps of this American “ultra- modernism” in his use of reference chords constructed from systematic intervallic layering; his points of reference here include, besides Charles Ives and Henry Cowell, also the theoretical writings of Joseph Schillinger and Nicolas Slonimsky. (Slonimsky is especially deserving of mention for being the first person in America to draw attention, in his book Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns, to the all-interval twelve-tone chord so frequently employed by Carter in his late works.)(21)Nicolas Slonimsky, Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1947), esp. pp. iii−iv and 24.

[ 23 ] Carter never entirely lost sight of the artistic legacy of early American modernism, not even in his middle period, when he engaged deeply (if critically) with the post-war European avant-garde.(22)See inter alia Anne C. Shreffler, “Elliott Carter and His America,” Sonus 14, no. 2 (spring 1994), pp. 38−66, esp. pp. 50f. and 61f.; and Nancy Yunhawa Rao, “Ruth Crawford’s Imprint on Contemporary Composition,” Ruth Crawford Seeger’s Worlds: Innovation and Tradition in Twentieth-Century American Music, ed. Ray Allen and Ellie M. Hisama (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2007), pp. 110−47, esp. pp. 120−25. Still, new facets of his artistic personality emerged in his late work, facets which run counter to several widespread prejudices and which could, and should, provide an opportunity for a more judicious overall assessment of his oeuvre. Even today, when a large part of his late work still awaits thorough analytic investigation, it is becoming increasingly clear, for example, that Carter, in his old age, moved far from his earlier predilection for highly complex and multi-layered musical architectures, which his critics occasionally faulted for expressing a recherché modernist focus on the material. And it is equally becoming clearer and clearer that his cosmopolitanism was not tantamount to a fixation on the European arts scene. It is not least with a view to revising such blanket judgments that there is much to be gained from a deeper and more thoroughgoing study of his late work.

(Translated from German by J. Bradford Robinson)

Footnotes

1. See above all David Schiff’s introduction to the new edition of his The Music of Elliott Carter (London: Faber and Faber, 1998), pp. 1−31, esp. pp. 29−31, and John Link, “Elliott Carter’s Late Music?,” in the progam booklet of the Tanglewood Contemporary Music Festival, July 20-24, 2008, pp. 79−81.

2. “Musik kann uns gefährlich werden” (Elliott Carter im Gespräch mit Christine Lemke-Matwey), Der Tagesspiegel (Berlin, April 20, 2009); quoted from the on-line version at http://www.tagesspiegel.de (accessed on November 16, 2010).

3. Theodor W. Adorno, “Spätstil Beethovens” (1937), in idem, Musikalische Schriften IV, Gesammelte Schriften 17, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1982), pp. 13–17; Edward Said, On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain (New York: Pantheon Books, 2006).

4. One indication of this is the fact that in his final years Carter, in sharp contrast to his earlier practice, once extracted a section from an existing score (ASKO Concerto, 1999−2000) and turned it into an independent work (Retracing). Conversely, he also integrated two finished compositions (Shard, 1997, and Call, 2003) in toto into large-scale new works (Luimen, 1997, and Réflexions, 2004).

5. See the discussions and bibliography in Joseph N. Straus, “Disability and ‘Late Style’ in Music,” The Journal of Musicology 25, no. 1 (winter 2008), pp. 3−45.

6. This also applies in particular to his opera What Next? of 1997–98, conceived jointly with Paul Griffiths. However, this product of a genuine collaboration with a writer represents a special case.

7. Paul Griffiths, “‘Its full choir of echoes’: The Composer in His Library,” Elliott Carter: A Centennial Celebration, Festschrift Series 23, ed. Marc Ponthus and Susan Tang (Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2008), pp. 23−40, quote on p. 25.

8. Schiff, The Music of Elliott Carter (see note 1), pp. 2–8, quote on p. 4.

9. Recently expressed in Edward Ragg, Wallace Stevens and the Aesthetics of Abstraction (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

10. Elliott Carter, Program note for In the Distances of Sleep, printed in the program booklet for the premiere in New York’s Zankel Hall, Carnegie Hall, on October 15, 2006.

11. Wallace Stevens, Collected Poetry and Prose, ed. Joan Richardson (New York: Library of America, 1997).

12. Ibid., p. 118.

13. This sketch is reproduced in Felix Meyer and Anne C. Shreffler, Elliott Carter: A Centennial Portrait in Letters and Documents (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2008), p. 337.

14. A similar expansion of the tonal space, both upward and downward, is also found in the final seven bars of the string part.

15. See e.g. Irving Sandler, "Abstrakter Expressionismus: Der Lärm des Verkehrs auf dem Weg zum Walden Pond," Amerikanische Kunst im 20. Jahrhundert: Malerei und Plastik, 1913−1993, ed. Christos M. Joachimides and Norman Rosenthal (Munich: Prestel, 1993), pp. 89−96 [catalogue of an exhibition held in the Martin Gropius Building, Berlin, May 8 – July 25, 1993].

16. “Composer’s Note” in Elliott Carter, Sound Fields for string orchestra (Hendon Music/ Boosey and Hawkes, 2007), n.p.

17. On Frankenthaler’s work see above all Alison Rowley, Helen Frankenthaler: Painting History, Writing Painting (London and New York: I. B. Tauris, 2007).

18. See Link’s discussion in Elliott Carter, Harmony Book, ed. Nicolas Hopkins and John F. Link (New York: Carl Fischer, 2002), “Appendix 2: The ‘Link’ Chords,” pp. 358-61, esp. p. 358.

19. Compare Jonathan W. Bernard’s distinction between “successive” and “simultaneous” textures in Carter’s music of the 1950s and ‘60s, in idem, “The Evolution of Elliott Carter's Rhythmic Practice.” Perspectives of New Music 26, no. 2 (1988): 164-203.

20. See Marguerite Boland, “Ritornello form in Carter’s Boston and ASKO concertos,” In Elliott Carter Studies (Cambridge University Press, 2012), 80-109.

21. Nicolas Slonimsky, Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1947), esp. pp. iii−iv and 24.

22. See inter alia Anne C. Shreffler, “Elliott Carter and His America,” Sonus 14, no. 2 (spring 1994): 38−66, esp. pp. 50f. and 61f.; and Nancy Yunhawa Rao, “Ruth Crawford’s Imprint on Contemporary Composition,” Ruth Crawford Seeger’s Worlds: Innovation and Tradition in Twentieth-Century American Music, ed. Ray Allen and Ellie M. Hisama (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2007), pp. 110−47, esp. pp. 120−25.

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor W. 1937. “Spätstil Beethovens.” In idem, Musikalische Schriften IV, Gesammelte Schriften 17. Ed. Rolf Tiedemann. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1982, pp. 13–17.

Bernard, Jonathan W. 1988. “The Evolution of Elliott Carter's Rhythmic Practice.” Perspectives of New Music 26, no. 2: 164-203.

Boland, Marguerite. 2012. “Ritornello form in Carter’s Boston and ASKO concertos.” In Elliott Carter Studies. Cambridge University Press, pp. 80-109.

Carter, Elliott. 2002. Harmony Book. Ed. Nicolas Hopkins and John F. Link. New York: Carl Fischer.

________. 2006. Program note for In the Distances of Sleep. In the program booklet for the premiere in New York’s Zankel Hall, Carnegie Hall, on October 15.

________. 2007. “Composer’s Note.” In Elliott Carter, Sound Fields for string orchestra. Hendon Music/Boosey and Hawkes.

Griffiths, Paul. 2008. “‘Its full choir of echoes’: The Composer in His Library,” Elliott Carter: A Centennial Celebration. Festschrift Series 23. Ed. Marc Ponthus and Susan Tang. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, pp. 23−40.

Lemke-Matwey, Christine. 2009. “Musik kann uns gefährlich werden” (Elliott Carter im Gespräch mit Christine Lemke-Matwey). Der Tagesspiegel. Berlin, April 20.

Link, John. 2008. “Elliott Carter’s Late Music?.” In the progam booklet of the Tanglewood Contemporary Music Festival, July 20-24, pp. 79−81.

Meyer, Felix and Anne C. Shreffler. 2008. Elliott Carter: A Centennial Portrait in Letters and Documents. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press.

Ragg, Edward. 2010. Wallace Stevens and the Aesthetics of Abstraction. Cambridge University Press.

Rao, Nancy Yunhawa. 2007. “Ruth Crawford’s Imprint on Contemporary Composition.” In Ruth Crawford Seeger’s Worlds: Innovation and Tradition in Twentieth-Century American Music. Ed. Ray Allen and Ellie M. Hisama. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, pp. 110−47

Rowley, Alison. 2007. Helen Frankenthaler: Painting History, Writing Painting. London and New York: I. B. Tauris.

Said, Edward. 2006. On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain. New York: Pantheon Books.

Sandler, Irving. 1993. “Abstrakter Expressionismus: Der Lärm des Verkehrs auf dem Weg zum Walden Pond,” In Amerikanische Kunst im 20. Jahrhundert: Malerei und Plastik, 1913−1993. Ed. Christos M. Joachimides and Norman Rosenthal. Munich: Prestel, pp. 89−96 [catalogue of an exhibition held in the Martin Gropius Building, Berlin, May 8 – July 25, 1993].

Schiff, David. 1998. The Music of Elliott Carter. London: Faber and Faber.

Shreffler, Anne C. 1994. “Elliott Carter and His America.” Sonus 14, no. 2: 38−66.

Slonimsky, Nicolas. 1947. Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

Stevens, Wallace. 1997. Collected Poetry and Prose. Ed. Joan Richardson. New York: Library of America.

Straus, Joseph N. 2008. “Disability and ‘Late Style’ in Music.” The Journal of Musicology 25, no. 1: 3−45.