A Kinetic Projection of Ideas: Rhythm and Phrasing in Elliott Carter’s Piano Sonata(*)

Douglas Rust

Abstract

Building upon new understandings of the form of Elliott Carter’s Piano Sonata (found in Meyer & Shreffler (2008)’s recent commentary on some of Carter’s documents), this article provides a perspective on the sophisticated ways that rhythmic patterns and phrasing coordinate with the frequent changes of unwritten time signatures (most clearly evident in the first movement of this piece), to position this sonata among the highest musical achievements from the United States in the 1940s. The new perspective offered here will help the reader to appreciate how small rhythmic groupings affect the expression of phrases, how these phrases are formed and how to interpret the significance of their order. It also offers valuable performance practice guidance based upon the composer’s sketches and documentary evidence. The insights shared here pertain to the Piano Sonata, but could be applied to other works, such as the String Quartet No. 1, the Sonata for Violoncello and Piano, or other pieces from this influential style period in Carter’s career.

Introduction

[ 1 ] Elliott Carter’s Piano Sonata signaled a rhythmic and metric sophistication that sounded original and new in the 1940s. In his favorable review of the piece, Virgil Thomson referred specifically to the innovations of its faster music: “The brilliant toccatalike passages, of which there are many, are to my ear completely original. I have never heard the sound of them or felt the feeling of them before. They are most impressive.” (Thomson, 1948). Richard Franko Goldman, who ranked this piece among the greatest piano sonatas in American music history, similarly paid special attention to rhythmic and metric patterning in the first movement: “The barring and grouping of the 16ths in the rapid-running sections of the movement (marked legato scorrevole) show the attention to detail that is characteristic of Carter: each fragment of phrase seems carefully thought out, but continuity is thereby achieved rather than impeded.” (Goldman, 1951, 86).(1)Similar views were expressed by Abraham Skulsky (1953), and William Glock (1955). For a contrasting perspective, see John Kirkpatrick (1948). Although the Carter Piano Sonata is well known, comparatively little attention has been paid to the sophisticated ways that small-scale rhythmic patterns and phrasing are coordinated with motivic development and frequent changes of meter to create large-scale formal processes in the “toccatalike” passages of Carter’s composition. Focusing primarily on the first movement, the perspective offered here illustrates how small rhythmic groupings are combined into phrases, how these phrases are grouped into larger formal units and how the phrasing is coordinated with the piece’s network of related motives. It also offers valuable performance practice guidance based upon the composer’s sketches and documentary evidence.

An ever-changing series of motives

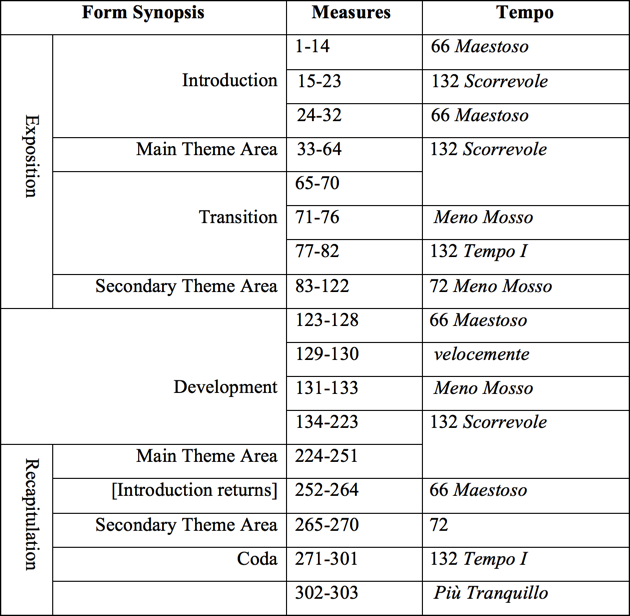

[ 2 ] Example 1 refers to the first movement of the piece, with a synopsis prepared by the composer in the first column and measure numbers and tempi from the published score in the second and third columns. Descriptions of musical form in this movement will refer back to Example 1.

Example 1

Elliott Carter, Piano Sonata/I, form synopsis and tempo changes.

[ 3 ] The form synopsis is part of an analysis of the piece that Carter sent to Edgard Varèse in a 1948 letter.(2)The analysis is reprinted in Meyer and Shreffler (2008, 77-79). It refers to specific page locations from an early Photostat version of his score whose pagination does not match the first edition, so a Photostat copy at the Library of Congress was used to verify location references. Carter’s analysis indicates how the two themes are introduced in very different ways. The main theme is heard for the first time in m. 36, following a succession of different motives that extends back to the very first measure. The second theme, on the other hand, has a more traditional arrival in m. 83, where it is presented in its entirety after the exposition of the main theme has concluded.(3)After the second theme is presented in its entirety, it recurs under the traditional contrapuntal operations of stretto (m.104), contrary motion (m. 106), augmentation (mm. 156-159) and transposition (mm. 265-269). Thus, the main theme is situated within a succession of related motives from which it emerges as part of a dynamic musical process, while the second theme appears fully formed in a conventional manner after a caesura.

[ 4 ] In addition to his form synopsis, Carter also provided a list of nine motives (labelled alphabetically) that are introduced at the outset and developed throughout the movement.(4)A photograph of the original may be found in Meyer and Shreffler (2008): 78. It is possible to group some of these motives together (and to associate them with other melodic shapes outside the original nine) by noticing which pitch intervals they hold in common.

Example 2

Elliott Carter, Piano Sonata/I, selected motives from the exposition

© Copyright 1948 by Mercury Music, Inc., Bryn Mawr, PA. Theodore Presser Co., Sole Representative

[ 5 ] Example 2 identifies four motives and their recurrences that, together, form a group of musical ideas that feature the pentatonic collection (or a pentatonic segment) in some way. Those with alphabetic labels match one of the nine motives Carter identified in his form analysis, while the others in this pentatonic group are original to this interpretation. A comparison between motive C and the main theme, which appears on the top left of this example, shows that they share their first four pitch classes (after the pickup) in common.(5)In a page of lecture notes, found in the Holograph Music Manuscripts of Elliott Carter (1932-1971) collection at the Library of Congress, the composer himself illustrated how the main theme derives from motive C. Lines drawn between the main theme and motive C in Example 2 replicate his diagram. Motive H begins with the first seven notes from the main theme’s first appearance at m. 34 (transposed up 10 semitones) and then it is extended by a suffix. A more abstract relationship is identified in the gapped scalar ascent at the bottom of the example, where upper notes of the melodic contour are beamed together to show how they span melodic intervals 5 and 7. While the melodic contours of the two gapped-scale examples do not match each other exactly, they both emphasize pentatonic intervals 5 and 7 that associate them abstractly with the other motives displayed. Together, the musical ideas expressed in the example form a group of related motives that include all versions of the main theme. They are heard most often in the first part of the exposition.

[ 6 ] The chain of motivic associations extends back even further because prominent members of this pentatonic group bear a resemblance to the very first two notes of the piece. The initial ascending octave leap from B2 to B4 – labeled “motive A” by Carter – can be related to the ascending octave span of motive C and its progeny. This interpretation extends a path of association from motive A in m. 1 to the first occurrence of motive H in m. 44. A second group of motives develops from the ascending-step pattern shown in Example 3.

Example 3

Elliott Carter, Piano Sonata/I, ascending-step motives from the exposition

© Copyright 1948 by Mercury Music, Inc., Bryn Mawr, PA. Theodore Presser Co., Sole Representative

The prominent ascending step that begins motive B begets the recurrent motive displayed below it and is eventually extended to form the more emphatic staccato ascending line of motive G. These ascending-step motives can be associated on a more abstract level with scalar ascending patterns that connect non-consecutive notes, such as the passage shown in mm. 51-53. One also could view the gapped scalar ascents, shown earlier in Example 2, as a hybrid combining the rising-scalar property of this motive family with the pentatonic-interval trait of the other. The motives and scalar patterns in this group do not relate specifically to either the first or the second themes of this sonata form. Instead, they function as melodic ideas to be developed in transitional or developmental passages of the piece or as markers that introduce or conclude formal sections.

[ 7 ] Ultimately, these associated motives in a variety of sizes express a language of large-scale form that Carter was developing at this time. Commenting on this aspect of the Piano Sonata, Carter wrote that “...all the ideas are in a constant state of expansion, contraction, intensification.” (Schiff 1998: 208) This approach to musical organization would become increasingly important for Carter in the following decades. As he wrote about his String Quartet No. 2 (1959): “There is little dependence on thematic recurrence which is replaced by an ever-changing series of motives and figures having certain internal relationships with each other.” (1970, 234) In the Piano Sonata, the increasing size and intricacy of the motives listed in Example 2 are key to the momentum and overall direction of the first movement. From the simple octave leap in m. 1 (Carter’s “motive A”) to the syncopated ascending contours of the main theme (around m. 35), culminating in the long and intricate gapped scale figurations in continuous sixteenth notes later in the movement, the lengthening of the motives is a formal process that underlies the faster motion and continuous flow of the Legato scorrevole. Shorter motives beget longer motives creating a dynamic growth of the music that is associated with their traits.

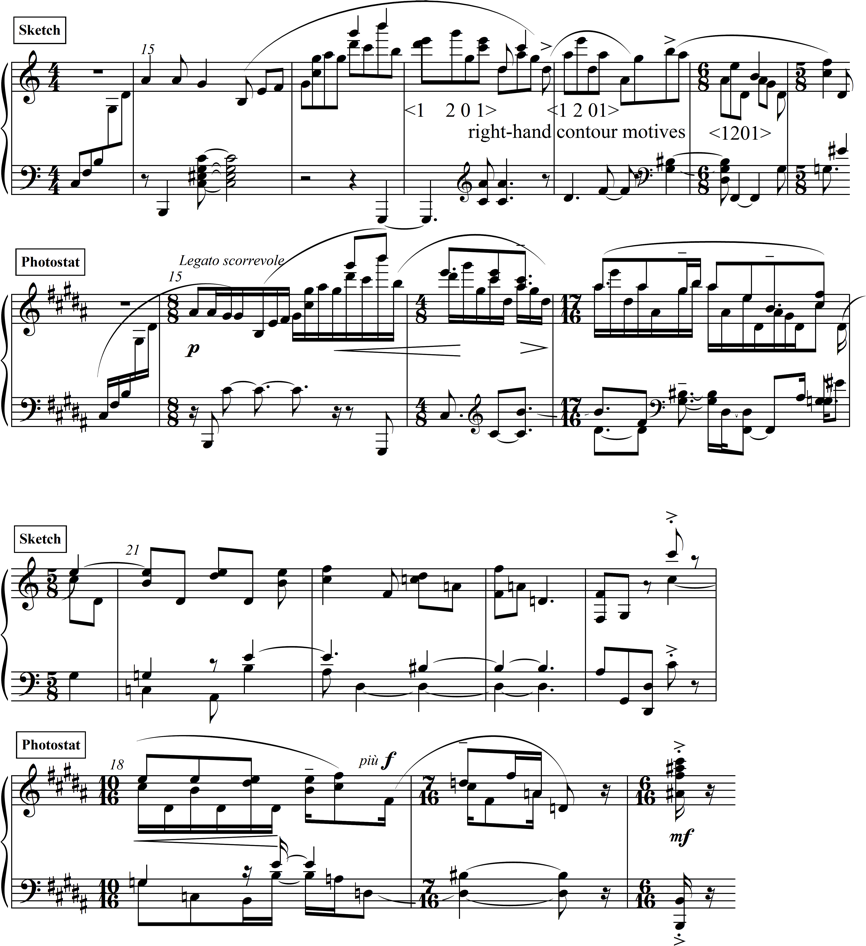

[ 8 ] To investigate the larger-scale patterns of phrasing in Carter’s Piano Sonata in more detail, it is helpful first to observe a few of its characteristic rhythmic features. During the many scorrevole passages, multiple levels of rhythmic activity interact. At the fastest level is the almost constant stream of sixteenth notes, while the second level results from melodic contour shapes that parse the continuous sixteenths into groups of two, three or more. As shown in Example 4, the stream of sixteenth notes played by the right hand divides into two- and three-note contour groups whose initial attack is higher in register than the subsequent notes. These local maxima are emphasized by other means as well.(6)“Maxima are the pitches at local high points in a contour plus the contour’s first and last pitch.” Morris (1993, 212-213) Articulations of the right hand (such as the tenuto markings) and rhythms in the accompaniment also work to reinforce most of the maxima in the contour of the uppermost line. This passage clearly creates a hierarchy between the notes that begin each rhythmic grouping and those that follow.

Example 4

Elliott Carter, Piano Sonata/I, mm. 51-55 (with slurs from Photostat)

© Copyright 1948 by Mercury Music, Inc., Bryn Mawr, PA. Theodore Presser Co., Sole Representative

[ 9 ] The patterns of two and three sixteenth notes in the example combine to form an even higher level of organization. For the present analysis, a “rhythmic cell” is defined as a sequence of contour groups that is either connected by a slur on the composer’s Photostat version of the sonata or bounded by rests.(7)Carter chose not to include most of the slurs (and time signatures) marked in the first movement when the piece was published, but referring back to these unpublished slurs brings to light some of Carter’s own melodic groupings. Referring back to Example 4, the rhythmic cells are indicated below the staff by brackets. At the next level of rhythmic hierarchy, the rhythmic cells are combined to produce phrases. The phrase in Example 4 is five measures long, beginning on the downbeat of m. 51 and continuing until a sudden change of dynamics and texture signals the return of motive H at m. 56 (not shown). From this perspective, it is possible to recognize four hierarchical levels ascending from the steady stream of sixteenth notes to the two- and three-note contour groups, to the bracketed sequence of rhythmic cells, to the formation of a longer phrase.

[ 10 ] Using the composer’s slurs or rest boundaries to define rhythmic cells occasionally leads to very long cells, containing measure after measure of uninterrupted sixteenth-note motion. In such cases, the analysis of melodic contour becomes especially helpful for interpretation. For instance, the gapped-scale passage that ends the main theme area spans seven measures of sixteenth notes and it has no slur notated on the published score, nor in any of the sketch versions (see Example 5).

Example 5

Elliott Carter, Piano Sonata/I, mm. 58-64

© Copyright 1948 by Mercury Music, Inc., Bryn Mawr, PA. Theodore Presser Co., Sole Representative

Here, the gapped-scale figuration unfolds in two waves that move towards more consistent repetition of rhythmic groups. The first wave begins at m. 58. Seven of the first eight pitches return one octave higher in m. 60.(8)Only the first pitch is different. The contour pattern is taken from the first gapped-scale passage, m. 50. Some of the contour groups in m. 59 also are heard at the end of the next measure, so m. 60 sounds something like an abridged combination of pitch-class patterns and contour patterns of the previous two bars. The second wave begins in m. 62 with contour groups of three and five sixteenths in the right hand – a sequence not previously heard in the phrase – which leads to another contour profile of mostly two-note groups.

[ 11 ] Longer rhythmic cells, like the one in Example 5, serve a quasi-cadential function in the first movement of Carter’s Piano Sonata. Such “cadential cells” generally end either with a gesture of closure – such as a caesura, or a two-note contour group repeated several times – or are suddenly interrupted by a new idea.(9)Schiff gives a few examples of these interruptions in his analysis of the sonata, stating that “The device of unexpected interruptions gives the music its improvisatory quality.” (1998, 209) The cell in Example 5 illustrates both the greater length and the repeated two-note contour groups characteristic of cadential cells. From the onset of the scorrevole section at the pickup to m. 33 to its conclusion in m. 79, there are forty-four rhythmic cells – mostly spanning different durations and following different melodic contours – grouped into six phrases:

Phrase 1. Mm. 33-43

Phrase 2. Mm. 44-50

Phrase 3. Mm. 51-55

Phrase 4. Mm. 56-64

Phrase 5. Mm. 65-70

Phrase 6. Mm. 71-79

Phrase formation and form

[ 12 ] Having seen how phrases in this sonata are built up hierarchically from contour groups and rhythmic cells, it remains to explore the larger-scale formal processes that operate in the first movement of Carter’s Piano Sonata. Chief among these are the increasing metrical regularity in presentations of the main theme, and increasing rhythmic coordination of the main theme, played by one hand, and the accompaniment, played by the other.

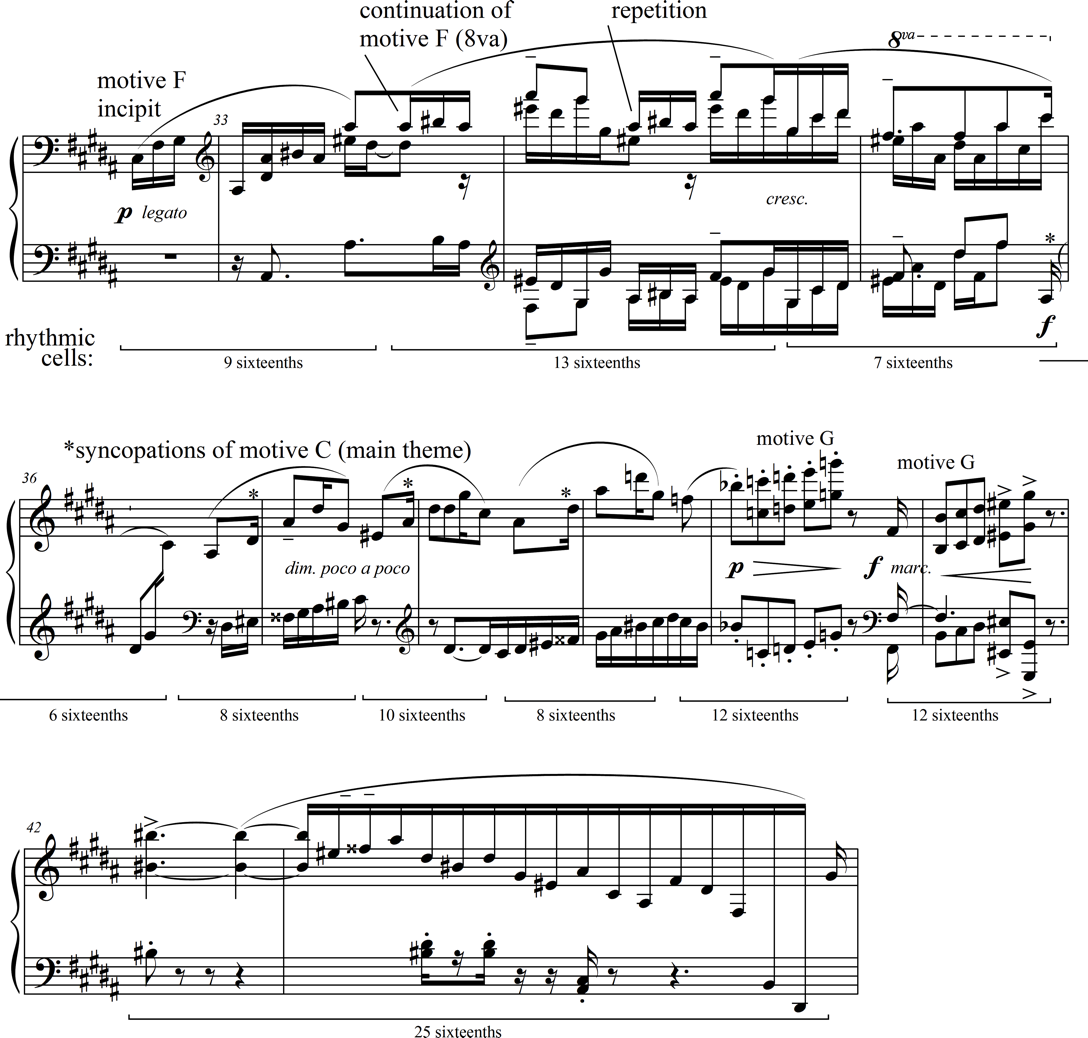

[ 13 ] The first phrase of the scorrevole is shown in Example 6. Brackets beneath the staff identify the rhythmic cells, with the length of each cell given in sixteenth notes.

Example 6

Elliott Carter, Piano Sonata/I, Phrase 1, mm. 33-43 (with slurs from Photostat)

© Copyright 1948 by Mercury Music, Inc., Bryn Mawr, PA. Theodore Presser Co., Sole Representative

The music in this phrase can be divided into three parts, with a strongly syncopated version of motive C (the main theme) in mm. 36-39, flanked by more rhythmically regular repetitions of motive F in mm. 33-35 and of motive G (in octaves) in mm. 40-41. The opening of the main theme is heard four times during the phrase but the entrances are irregularly spaced, thwarting any impression of regular meter that might arise as a byproduct of the repetition. Compare these measures with the latter half of phrase 2 (shown in Example 7). As the pitches A♯5, F♯6 and D♯6 begin to repeat in the upper register, an overlapping rhythmic pattern of six beats briefly projects an emerging impression of meter around mm. 46-47 (rhythmic cells 4 and 5). The pattern is heard initially in cell 3, where two prior occurrences of A♯ F♯ and D♯ encourage a parsing of the cell into two overlapping parts – despite the single slur written by the composer. In the next measure (m. 47), Carter aligns the slurs with the recurring pattern as the sense of rhythmic regularity briefly comes into focus.

Example 7

Elliott Carter, Piano Sonata/I, mm. 44-50 (with slurs from Photostat)

© Copyright 1948 by Mercury Music, Inc., Bryn Mawr, PA. Theodore Presser Co., Sole Representative

[ 14 ] Continuing this tendency towards more metric regularity, phrases 3 and 4 present rhythmic cells of similar durations more often than one hears in the first two phrases. Rhythmic cells of seven sixteenth note durations continue unabated for two bars in phrase 3 (see mm. 51-52, shown in Example 4) before a five-note group arrives to add a little variety. Pitch contour patterns reinforce these rhythmic groupings in mm. 51-54, beginning with the pitches D5, C♯5, F♯5, and gradually moving up in register until rhythmic cell 7 brings back the same F♯-D♯-A♯ pitch classes that formed a metric grouping earlier in phrase 2 (see Example 7, mm. 46-47).(10)Sometimes this pitch pattern is notated with longer note values connected by beams and at other times it occurs as a more subtle connection between peaks in the melodic contour. Still, it remains quite audible across mm. 51-53.

[ 15 ] Phrase 4 continues the metric regularity of the previous phrase while it introduces the return of motive H and the five-note slur groupings assigned to it. The appearance of motive H constitutes the final occurrence of the main theme in the exposition (The reader will recall that motive H is an extended version of the main theme), and brings the main theme area to a close. This significant moment in the form coincides perfectly with the culmination of a long progression from metric irregularity within phrase 1 (m. 33, shown in Example 6) to the comparatively regular recurrence of five-note rhythmic cells that begin phrase 4. All of the rhythmic cells in the first two measures of phrase 4 span durations of five sixteenth notes exclusively – before a gapped-scale passage draws the phrase towards its conclusion in m. 64.

[ 16 ] A complementary aspect of the main theme area is the grouping of phrases in pairs. Phrases 1-2 and phrases 3-4 form such pairs – with the second phrase of each pair involving a gapped-scale figuration that draws it towards its conclusion. This arrangement establishes an antecedent/consequent relationship between the phrases when the second phrase in each pair concludes more definitively. Phrases 5 and 6 also form a pair. They span the passage from m. 65 to m. 79 that was labeled by Carter as the transition (see his analysis in Example 1). Phrase 6 concludes definitively with a cadential cell in mm. 77-79, while phrase 5 ends more abruptly when the onset of new melodic ideas (and their accompanying tempo change) announce the beginning of the sixth phrase. As with the other two phrase pairs, this one saves the most conclusive cadential cell for the last phrase.

[ 17 ] With the main theme area complete, phrases 5 and 6 reverse the tendency towards more metric regularity heard in the earlier phrase pairs. The regular repetition of seven-note rhythmic cells in phrase 3 progressing to five-note cells in phrase 4 yields a more rapid periodicity that becomes increasingly apparent to the ear. In contrast, phrase 5 repeats a longer passage of music from the downbeat of m. 66 to the first half of m. 67 – encompassing a duration of fourteen sixteenth notes slurred into three rhythmic cells. This passage repeats beginning at the second half of m. 67 and continuing until the end of m. 68. Such a lengthy unit of repetition retreats from the perceptual immediacy of the five-note repeated cell in phrase 4 and the corresponding perception of regularity becomes more abstract. Although a shorter rhythmic cell repeats briefly at the end of this phrase, the onset of phrase 6 moves towards even less metric regularity. In this final phrase of the transition, there are no straightforward instances of repetition until the descending octaves of the cadential cell that ends the passage.

[ 18 ] The gradually emerging metrical regularity in the main theme area is reinforced by the increasing rhythmic alignment of the main theme, played by the right hand, and the accompaniment in the left. In the early parts of the movement the main theme and its accompaniment are notably non-aligned. Referring back to Example 6, one may observe that the four instances of Carter’s main theme (marked with asterisks) feature phrase slurs that do not match the rhythmic groupings of the accompanimental left hand – in contrast to the rhythmic coordination evident in the other parts of the passage. Note that the dyads and accented notes of the right hand are coordinated with the rhythms of the left hand from mm. 33-35, while the two hands work together in parallel at the end of the example (Carter’s “motive G”). In contrast, the middle of the phrase (which introduces the main theme) offers very little rhythmic cooperation between the hands, as stepwise contours in the left hand do not line up with motivic repetitions, slurs, or tenuto markings in the right. Partly for this reason, the main theme stands apart from the accompaniment in this context. As the left hand plays long successions of sixteenth notes whose scalar contours do not group into rhythms that match the right hand, the resulting contrast subtly helps the emergence of the main theme to sound more noticeable, despite the fact that it begins in the middle of the phrase.

[ 19 ] When the main theme returns in the next phrase, it occurs only once in its original form (at measure 44), then it is varied freely in the next bar and the end of that variation is fragmented into a rhythmic pattern that repeats four times in measures 46-48, forming the longest-spanning rhythmic repetition within this particular rhythmic cell.(11)Note that the temporary appearance of regular rhythmic groupings in these measures is highlighted briefly by matching slurs in both hands. The resulting pattern brings both hands into the same accent pattern in m. 48. The main theme, which showed no cooperation between hands in its first appearance, now leads to a passage with simultaneous accents in both hands. At the end of its section of the exposition (see Example 8), the main theme completes its transformation by featuring parallel left-hand and right-hand accents throughout.

Example 8

Elliott Carter, Piano Sonata/I, mm. 56-57

© Copyright 1948 by Mercury Music, Inc., Bryn Mawr, PA. Theodore Presser Co., Sole Representative

In m. 60-61, accented notes in the left hand align with contour groups in the right, and the two hands finally attain total alignment as motive G arrives in the left hand. Once full rhythmic coordination between the hands is finally achieved, the main theme area moves quickly towards closure.

[ 20 ] When the main theme returns in the recapitulation, it is treated differently. First of all, it is presented separately from the introductory material that had preceded it in the exposition.(12)Carter’s analysis identifies m. 224 as the beginning of the recapitulation, which begins just as the exposition did with motive F, but this time two other motives – the “recurrent motive” (see Example 3) and motive G – separate motive F from the main theme. The main theme begins its own phrase, rather than interrupting the repeat of motivic developments already underway. Yet the difference in rhythmic setting is even more significant than the phrasing. Unlike the exposition, which resolves the contrasting rhythmic groupings between hands by having the left hand take up material in m. 56 that resembles the right-hand motive, the recapitulation transforms the left hand’s ascending scalar accompaniment (from m. 36 – the first appearance of the main theme) to match the phrasing of the right. In other words, the reconciliation of rhythmic differences between hands occurs not by abandoning the left-hand accompaniment of the initial main theme, but by varying its phrasing to match that of the right hand. This left hand/right hand synchronization occurs at the return of the extended main theme (motive H) in mm. 229, 230 and 231 of the recapitulation, where left-hand slurs end concurrently with slurs in the right hand. Concurrent phrase endings between hands happen also at the decisive conclusion of the main theme when it ascends to D6 in mm. 239-240, followed by some gapped-scale figuration to close the phrase.

[ 21 ] In the coda, the sense of resolution provided by the rhythmic alignment of the hands is reinforced by the cadential function of repeated short rhythmic groupings heard earlier in the cadential cells. Over much of the coda, smaller rhythmic groupings are played by both hands in rhythmic unison (sometimes in parallel octaves) to emphasize that section’s concluding function. In all of these examples, the sonata’s contrasting textural layers and diverse rhythmic and metric patterns are best understood not as style traits, but as the result of large-scale formal processes that work out gradually over the course of the entire movement.

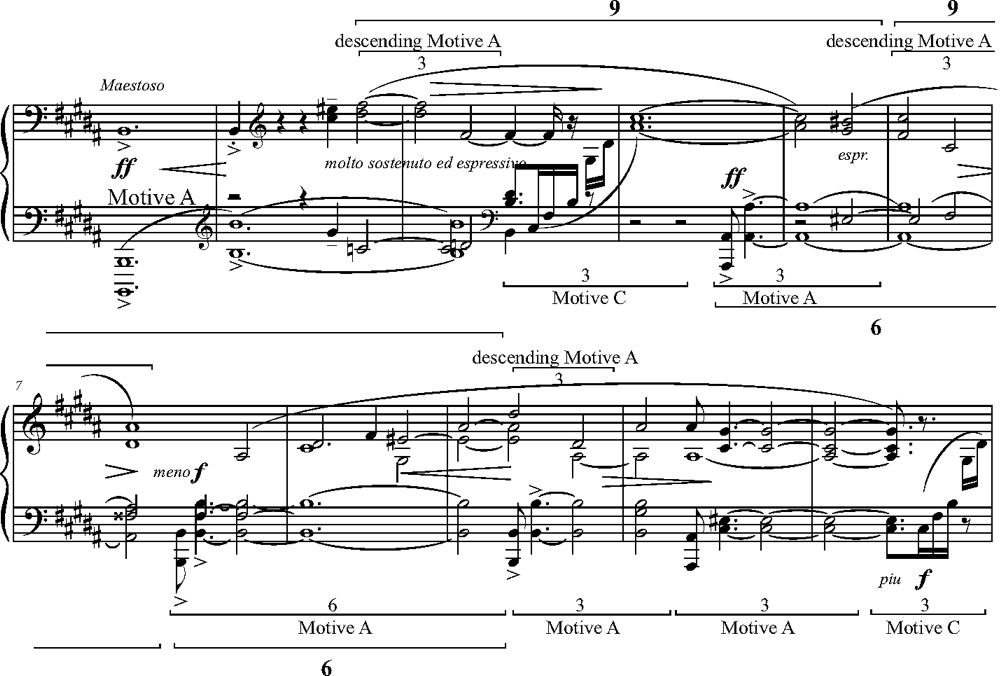

[ 22 ] Carter’s approach to musical form as a process is foreshadowed early on. Example 9 shows the opening of the sonata, the first of several Maestoso passages that recur at key moments throughout the movement. Each maestoso passage consists of a succession of introductory motives separated by rests.

Example 9

Elliott Carter, Piano Sonata/I, mm. 1-11

© Copyright 1948 by Mercury Music, Inc., Bryn Mawr, PA. Theodore Presser Co., Sole Representative

Beginning on the third half note of m. 4, motive A (the accented ascending octave) recurs every six half-note beats, while the descending octave version recurs every nine beats (starting on the third half note of m. 2). Together, they place an octave motion every three beats until their simultaneous occurrence in m. 9 completes the polyrhythmic cycle. Anticipation of this concurrent motivic statement is increased by the absence of either motive for the span of six half notes preceding it, in marked contrast to the earlier measures, in which an ascending-octave or descending-octave motive begins every three half notes. Immediately following bar nine, the two hands play the same rhythm together to echo the convergence of these motives.

Carter rebarred

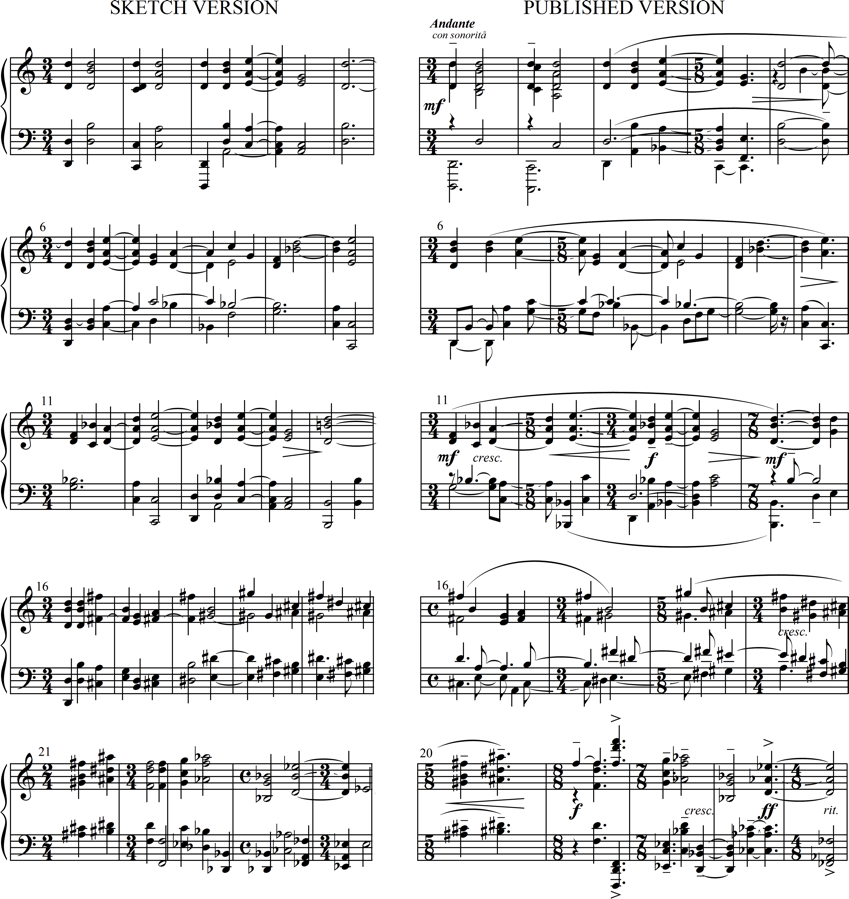

[ 23 ] In none of his previous compositions does Carter change meter as frequently as in the Piano Sonata, nor does he use such a variety of time signatures. There are twenty-six different time signatures written in the composer’s Photostat version of the first movement; these were omitted from the published score for the sake of clarity (Schiff, 1983, p. 128). Although the general effect of all these meter changes is to produce a relatively seamless rhythmic continuum, the choice of meters and placement of bar lines in the sonata is not arbitrary, nor are the downbeats irrelevant. Carter’s sketches for this piece include versions of some passages which are cast in simpler metric settings that place the bar lines differently.(13)These sketch materials are kept in the collection Holograph Music Manuscripts of Elliott Carter (1932-1971) at the Library of Congress, which includes some 200 pages of sketch material for the Piano Sonata, along with Photostat and autograph copies of the score. Comparing the sketch versions of these passages to their rebarred published versions can help explain why the composer chose the time signatures he did.

[ 24 ] While at times it appears that Carter drafted passages using irregular meter, some of his meter changes were the result of shortening individual note durations, and leaving the notated metric placement of the surrounding measures unchanged. Example 10 shows the first twenty-four measures of the second movement in a sketch version and in the published version.(14)Holograph Music Manuscripts of Elliott Carter (1932-1971), box labeled “Piano Sonata”, Folio II, page 23. Another, less complete version is found on page 22 and still another fragment in Box 5, Folio I, page 2.

Example 10

Elliott Carter, Piano Sonata/I, mm. 1-24, sketch version and published version

© Copyright 1948 by Mercury Music, Inc., Bryn Mawr, PA. Theodore Presser Co., Sole Representative

[ 25 ] Although the sketch uses  meter almost exclusively, the published version includes

meter almost exclusively, the published version includes  on only nine of the twenty-four measures. Most of the differences between versions occur where durations of a half note or longer are shortened by half a beat, often producing a measure of

on only nine of the twenty-four measures. Most of the differences between versions occur where durations of a half note or longer are shortened by half a beat, often producing a measure of  . This sort of meter adjustment affects measures 4-5, 7-10, 12, 15, 18 and 23. In the published version, consecutive bars of

. This sort of meter adjustment affects measures 4-5, 7-10, 12, 15, 18 and 23. In the published version, consecutive bars of  are found only at the beginning of this passage (mm. 1-2) and at the halfway point (mm. 13-14). Other metric differences occur in the last four measures, where the lengthening of note durations yields a broadening effect. Yet despite the irregularity of meter introduced, the composer maintains the metric placement of most notes on his sketch: notes sketched on the downbeat almost always remain on the downbeat, tied notes remain tied, and most other notes retain their respective positions in the measure (the exception is measure 16).(15)The first edition moves the melodic F♯5 to the downbeat of m. 16, thus placing them on an equal footing with the F♯5s that follow on the downbeats of mm. 17, 19 and 20. A step progression can be heard extending from the F♯5 in m. 16 to the G♯5 in m. 18 (beginning the phrase slur) and finally to the A♯5 in m. 20 (ending the phrase slur).

are found only at the beginning of this passage (mm. 1-2) and at the halfway point (mm. 13-14). Other metric differences occur in the last four measures, where the lengthening of note durations yields a broadening effect. Yet despite the irregularity of meter introduced, the composer maintains the metric placement of most notes on his sketch: notes sketched on the downbeat almost always remain on the downbeat, tied notes remain tied, and most other notes retain their respective positions in the measure (the exception is measure 16).(15)The first edition moves the melodic F♯5 to the downbeat of m. 16, thus placing them on an equal footing with the F♯5s that follow on the downbeats of mm. 17, 19 and 20. A step progression can be heard extending from the F♯5 in m. 16 to the G♯5 in m. 18 (beginning the phrase slur) and finally to the A♯5 in m. 20 (ending the phrase slur).

[ 26 ] Comparing the sketches for mm. 15-20 (the first passage in the scorrevole) with Carter’s Photostat version indicates how the phrasing shaped the placement of bar lines in ways that are significant for performance (see Example 11).(16)There are two versions of the Photostat score in the Elliott Carter collection at the Library of Congress, one of which contains substantial revisions of pages 12, 15, 16 and 34 so that it corresponds exactly to the first edition. This is the version shown in Example 11.

Example 11

Elliott Carter, Piano Sonata/I, mm. 1-24, sketch version and published version

© Copyright 1948 by Mercury Music, Inc., Bryn Mawr, PA. Theodore Presser Co., Sole Representative

Here, Carter made significant changes to the notated meter in the second half of this excerpt. Note that, in the revised version, most bar lines coincide with phrasing slurs (if one allows for some sixteenth-note pickups). Since the slurs were omitted in the published version, the bar lines take on a special significance as a guide to phrasing.

[ 27 ] There are at least three sketches of this passage in the Library of Congress archive and each one has been barred differently.(17)Two sketches of this passage may be found in the Elliott Carter Collection, in the box labeled “Piano Sonata”, Folio II, one on either side of page 18. The version shown in Example 11 comes from one side of this page. (Another version, similar to the one shown in Example 11, is found in Folio I, page 17.) The version shown in Example 11 matches the first edition most closely. Assuming a key signature of five sharps, the pitches of the sketch version match those of the Photostat rather closely, even though its metric organization is dramatically different. Surprisingly, the first half of the sketch is written in  time (in fact, another sketch version of this passage, written on the other side of the page, uses

time (in fact, another sketch version of this passage, written on the other side of the page, uses  almost exclusively with only a single bar of

almost exclusively with only a single bar of  used near the end). Eighth notes in the sketch are changed to sixteenth notes in the Photostat, and a number of bar lines – highlighting important motives in the passage – are removed. For example, consider how bar 17 of the Photostat corresponds to two and a half measures of the sketch. The downbeats of measures 17, 18 and 19 on the sketch emphasize the recurrence of a contour motive (from the figuration of the right hand) that peaks, then concludes on its lowest pitch. Not only does this motive recur three times, but the first and third occurrences of the idea are followed by the same two- and three-pitch motives transposed down one octave (and reordered). Placing this contour motive consistently on downbeats may have given it more emphasis than the composer wanted, which may explain why he removed the bar line in the finished Photostat. Also, he eliminated another sketched bar line from the first half of this passage, combining bars 15-16 of his sketch into bar 15 on the Photostat. Meanwhile, measure 18 of the Photostat is moved to coincide with the beginning of a motive that returns several times in the piece,(18)See mm. 69-70, 226-7, and possibly also in the development section at mm.186-190. and that may explain why the composer chose to group the figure together in one measure – highlighting its first accented note with a bar line. The most significant change of bar line places C♯6, which serves as the goal of this passage, on the downbeat of m. 20.

used near the end). Eighth notes in the sketch are changed to sixteenth notes in the Photostat, and a number of bar lines – highlighting important motives in the passage – are removed. For example, consider how bar 17 of the Photostat corresponds to two and a half measures of the sketch. The downbeats of measures 17, 18 and 19 on the sketch emphasize the recurrence of a contour motive (from the figuration of the right hand) that peaks, then concludes on its lowest pitch. Not only does this motive recur three times, but the first and third occurrences of the idea are followed by the same two- and three-pitch motives transposed down one octave (and reordered). Placing this contour motive consistently on downbeats may have given it more emphasis than the composer wanted, which may explain why he removed the bar line in the finished Photostat. Also, he eliminated another sketched bar line from the first half of this passage, combining bars 15-16 of his sketch into bar 15 on the Photostat. Meanwhile, measure 18 of the Photostat is moved to coincide with the beginning of a motive that returns several times in the piece,(18)See mm. 69-70, 226-7, and possibly also in the development section at mm.186-190. and that may explain why the composer chose to group the figure together in one measure – highlighting its first accented note with a bar line. The most significant change of bar line places C♯6, which serves as the goal of this passage, on the downbeat of m. 20.

[ 28 ] The fact that Carter rebarred this short passage three times before entering it onto his Photostat score illustrates a remarkable aspect of his compositional methods. He first used  meter as a neutral backdrop upon which to sketch his ideas; then he adjusted the meters at a later stage to place the bar lines where they would highlight important motives and support the phrasing he had in mind.

meter as a neutral backdrop upon which to sketch his ideas; then he adjusted the meters at a later stage to place the bar lines where they would highlight important motives and support the phrasing he had in mind.

[ 29 ] Not all passages in the Piano Sonata underwent such drastic metric revision, nor were they all sketched in  meter. Some, like the syncopated main theme, were sketched from the beginning in a succession of different meters. In fact, most of the different sketch versions of the main theme use the same meters that are used in the published score.(19)There is a version of the main theme sketched on the back of one of Carter’s counterpoint exercises for Nadia Boulanger that closely corresponds with the published score of the sonata [I am grateful to Stephen Soderberg at the Library of Congress for bringing this to my attention. (Soderberg 2012, 241)]. The rhythms, contours and bar lines in this sketch version match the recapitulation of the main theme at mm. 235-239. Only pitch adjustments are needed to make this sketch match the score precisely. Yet the same concern for the metric placement of the motive that we observed in Example 11 is evident also in the published versions of the main theme. In the recapitulation, for example, the main theme occurs seven times – each time with its syncopated six-note motif beginning on a downbeat with a sixteenth-note pickup. Thus, bar lines in this sonata are placed in service of the melodic motives and phrasing, to indicate the unique accent pattern associated with each motive or variant. The most important motives remain in a constant state of flux throughout this composition and their recognition as motives depends in part on the metric accents indicated by the bar lines.

meter. Some, like the syncopated main theme, were sketched from the beginning in a succession of different meters. In fact, most of the different sketch versions of the main theme use the same meters that are used in the published score.(19)There is a version of the main theme sketched on the back of one of Carter’s counterpoint exercises for Nadia Boulanger that closely corresponds with the published score of the sonata [I am grateful to Stephen Soderberg at the Library of Congress for bringing this to my attention. (Soderberg 2012, 241)]. The rhythms, contours and bar lines in this sketch version match the recapitulation of the main theme at mm. 235-239. Only pitch adjustments are needed to make this sketch match the score precisely. Yet the same concern for the metric placement of the motive that we observed in Example 11 is evident also in the published versions of the main theme. In the recapitulation, for example, the main theme occurs seven times – each time with its syncopated six-note motif beginning on a downbeat with a sixteenth-note pickup. Thus, bar lines in this sonata are placed in service of the melodic motives and phrasing, to indicate the unique accent pattern associated with each motive or variant. The most important motives remain in a constant state of flux throughout this composition and their recognition as motives depends in part on the metric accents indicated by the bar lines.

Conclusion

[ 30 ] The dynamic growth of rhythmic and motivic processes in the Piano Sonata marks a new chapter in the career of Elliott Carter, who, in a radio lecture, described the opening section of the piece as, “the first passage in my works that is not primarily thematic” (1960, 213). Every phrase, every motive seems to follow a trajectory of ongoing rhythmic development. Unlike the Symphony No. 1, the Holiday Overture and other Carter compositions of the early 1940s in which the theme is presented at or near the beginning of the work, the main theme of the Piano Sonata evolves gradually from smaller motivic components, projecting an associative path that connects motives of different sizes and characteristics. The meter changes constantly so that the bar lines preserve the metric accent patterns of important motives. All of this motivic activity unfolds over a background of rhythmic cells that coordinate into phrases and produce musical direction on a larger scale. Cells within these phrases wax and wane to regulate the pace of ideas and the varying sense of metric regularity.(20)British musicologist Wilfrid Mellers explained these technical innovations in cultural terms as he wrote, “This tendency to think of rhythm in its smallest rather than largest units is a salient feature of American music…. (1965, 104-5). These processes continue as the different accompaniments to the main theme gradually draw the pianist’s hands into rhythmic agreement over the course of the exposition and later present an even more complete reconciliation during the recapitulation. Together, Carter’s sensitive balance of rhythm, meter and phrasing forge an expressive language that was embraced as new and exciting by his contemporaries and that places this work among the greatest musical achievements of its time.

Footnotes

* The author gratefully acknowledges the generous assistance of the staff at the Library of Congress Music Division, especially Stephen Soderberg, in the preparation of this research. Also, I thank the editorial board of Elliott Carter Studies Online, whose expert suggestions have significantly influenced the finished version of this article.

1. Similar views were expressed by Abraham Skulsky (1953), and William Glock (1955). For a contrasting perspective, see John Kirkpatrick (1948).

2. The analysis is reprinted in Meyer and Shreffler (2008, 77-79). It refers to specific page locations from an early Photostat version of his score whose pagination does not match the first edition, so a Photostat copy at the Library of Congress was used to verify location references.

3. After the second theme is presented in its entirety, it recurs under the traditional contrapuntal operations of stretto (m.104), contrary motion (m. 106), augmentation (mm. 156-159) and transposition (mm. 265-269).

4. A photograph of the original may be found in Meyer and Shreffler (2008): 78.

5. In a page of lecture notes, found in the Holograph Music Manuscripts of Elliott Carter (1932-1971) collection at the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/collections/elliott-carter/), the composer himself illustrated how the main theme derives from motive C. Lines drawn between the main theme and motive C in Example 2 replicate his diagram.

6. “Maxima are the pitches at local high points in a contour plus the contour’s first and last pitch.” Morris (1993, 212-213).

7. Carter chose not to include most of the slurs (and time signatures) marked in the first movement when the piece was published, but referring back to these unpublished slurs brings to light some of Carter’s own melodic groupings.

8. Only the first pitch is different. The contour pattern is taken from the first gapped-scale passage, m. 50.

9. Schiff gives a few examples of these interruptions in his analysis of the sonata, stating that “The device of unexpected interruptions gives the music its improvisatory quality.” (1998, 209)

10. Sometimes this pitch pattern is notated with longer note values connected by beams and at other times it occurs as a more subtle connection between peaks in the melodic contour. Still, it remains quite audible across mm. 51-53.

11. Note that the temporary appearance of regular rhythmic groupings in these measures is highlighted briefly by matching slurs in both hands.

12. Carter’s analysis identifies m. 224 as the beginning of the recapitulation, which begins just as the exposition did with motive F, but this time two other motives – the “recurrent motive” (see Example 3) and motive G – separate motive F from the main theme.

13. These sketch materials are kept in the collection Holograph Music Manuscripts of Elliott Carter (1932-1971) at the Library of Congress, which includes some 200 pages of sketch material for the Piano Sonata, along with Photostat and autograph copies of the score.

14. Holograph Music Manuscripts of Elliott Carter (1932-1971), box labeled “Piano Sonata”, Folio II, page 23. Another, less complete version is found on page 22 and still another fragment in Box 5, Folio I, page 2.

15. The first edition moves the melodic F♯5 to the downbeat of m. 16, thus placing them on an equal footing with the F♯5s that follow on the downbeats of mm. 17, 19 and 20. A step progression can be heard extending from the F♯5 in m. 16 to the G♯5 in m. 18 (beginning the phrase slur) and finally to the A♯5 in m. 20 (ending the phrase slur).

16. There are two versions of the Photostat score in the Elliott Carter collection at the Library of Congress, one of which contains substantial revisions of pages 12, 15, 16 and 34 so that it corresponds exactly to the first edition. This is the version shown in Example 11.

17. Two sketches of this passage may be found in the Elliott Carter Collection, in the box labeled “Piano Sonata”, Folio II, one on either side of page 18. The version shown in Example 11 comes from one side of this page. (Another version, similar to the one shown in Example 11, is found in Folio I, page 17.)

18. See mm. 69-70, 226-7, and possibly also in the development section at mm.186-190.

19. There is a version of the main theme sketched on the back of one of Carter’s counterpoint exercises for Nadia Boulanger that closely corresponds with the published score of the sonata [I am grateful to Stephen Soderberg at the Library of Congress for bringing this to my attention. (Soderberg 2012, 241)]. The rhythms, contours and bar lines in this sketch version match the recapitulation of the main theme at mm. 235-239. Only pitch adjustments are needed to make this sketch match the score precisely.

20. British musicologist Wilfrid Mellers explained these technical innovations in cultural terms as he wrote, “This tendency to think of rhythm in its smallest rather than largest units is a salient feature of American music.... (1965, 104-5).

Works Cited

Bernard, Jonathan W. 1988. “The Evolution of Elliott Carter’s Rhythmic Practice.” Perspectives of New Music 26, no. 2 (Summer): 164-203.

________. 1995. “Elliott Carter and the Modern Meaning of Time.” Musical Quarterly 79, no. 4. (Winter):644-682.

________. 1997. Collected Essays and Lectures, 1937-1995. Ed. Jonathan W. Bernard. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

________. 2012. “The True Significance of Elliott Carter’s Early Music.” In Elliott Carter Studies. Ed. Marguerite Boland and John Link. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 3-32.

Carter, Elliott.1955. “The Rhythmic Basis of American Music.” The Score and I.M.A. Magazine 12. (June): 27-32. Reprinted in Elliott Carter, Collected Essays and Lectures, 1937-1995. Ed. Jonathan W. Bernard (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 1997), 57-62.

________. 1960. “The Composer’s Choices.” Radio lecture commissioned by the Fromm Foundation. Reprinted in Elliott Carter, Collected Essays and Lectures, 1937-1995, ed. Jonathan W. Bernard (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 1997), 210-214.

________. 1965. “The Time Dimension in Music.” Music Journal 23/8. (November): 29-30. Reprinted in Elliott Carter, Collected Essays and Lectures, 1937-1995, ed. Jonathan W. Bernard (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 1997), 224-228.

________. 1970. “String Quartets No. 1, 1951, and 2, 1959.” Sleeve notes for a recording by the Composers String Quartet. Nonesuch Records H-71249. Reprinted in Elliott Carter, Collected Essays and Lectures, 1937-1995, ed. Jonathan W. Bernard (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 1997), 231-235.

________. 1976. “Music and the Time Screen.” In Current Thought in Musicology, ed. John W. Grubbs (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press), 63-88. Reprinted in Elliott Carter, Collected Essays and Lectures, 1937-1995, ed. Jonathan W. Bernard (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 1997), 262-280.

________. 1983. “Night Fantasies and Piano Sonata.” Sleeve notes for a recording by Paul Jacobs. Nonesuch Records 79047-1.

Edwards, Allen. 1971. Flawed Words and Stubborn Sounds: A Conversation with Elliott Carter. New York: Norton.

Glock, William. 1955. “A Note on Elliott Carter.” The Score and I.M.A. Magazine 12 (June): 47-52.

Goldman, Richard Franko. 1951. “Current Chronicle.” Musical Quarterly 37, no. 1 (January): 83-89. Reprinted in Selected Essays and Reviews 1948-1968, ed. Dorothy Klotzman (Brooklyn: Institute for Studies in American Music, 1980), 69-74.

Link, John. 1994a. “Long-Range Polyrhythms in Elliott Carter’s Recent Music.” Ph.D. diss., City University of New York.

________. 1994b. “The Composition of Elliott Carter’s Night Fantasies.” Sonus 14, no. 2 (Spring): 67-89.

Marvin, Elizabeth West and Paul A. LaPrade. 1987. “Relating Musical Contours: Extensions of a Theory for Contour.” Journal of Music Theory 31, no. 2: 225-267.

Mellers, Wilfrid. [1965] 1987. Music in a New Found Land. Reprint, New York: Oxford University Press.

Meyer, Felix and Anne C. Schreffler. 2008. Elliott Carter: A Centennial Portrait in Letters and Documents. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press.

Perkyns, Jane E. Gormley. 1990. “An Analytical Study of Elliott Carter’s Piano Sonata.” DMA diss., University of British Columbia.

Schiff, David. 1998. The Music of Elliott Carter. 2nd Ed. London: Faber, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

________. 2009. "Carter, Elliott." In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/05030.

Soderberg, Stephen. 2012. “At the edge of creation: Elliott Carter’s sketches in the Library of Congress.” In Elliott Carter Studies, ed. Marguerite Boland and John Link. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 236-250.