An Adventure in Form: Elliott Carter’s “Like a Bulwark” (2009)

Brenda Ravenscroft

Abstract

The question of how to shape form in a post-tonal context was a source of inspiration for Elliott Carter’s lifelong exploration of musical time. Avoiding predetermined forms, his two primary compositional techniques for creating large-scale form – long-range polyrhythms and textural stratification – involve temporal control. These techniques are omnipresent in his instrumental compositions, and play an equally important role in Carter’s vocal writing, in conjunction with the influence exerted by the formal structure of his carefully chosen texts. Instrumental interludes reflect stanzaic or semantic breaks in the poems, and textual characters often generate the contrasting musical streams of his polyphonic textures.

This essay examines Carter’s approach to form when it deviates from these established norms. Marianne Moore’s poem “Like a Bulwark,” set as the opening song in What are Years (2009), does not present clearcut characters, depriving Carter of a textual source on which to base his interacting contrapuntal streams. Rather than reflecting the two-part form of the poem, Carter creates an independent ternary structure – and there are no overarching polyrhythms guiding the large-scale formal structure. A close analysis of “Bulwark,” reveals Carter’s substitution of short-lived pulses and accelerandos for polyrhythms, the nature of stratification in the absence of character streams, his preference for gradual processes over sudden contrasts in shaping the ternary form, and the role that pitch structure plays in both large-scale continuity and in moment-to-moment progression.

[ 1 ] The question of how to shape form in a post-tonal context – which has presented composers with a challenge for well over a century – was a source of inspiration for Elliott Carter throughout his long compositional life, spurring his well-documented exploration of musical time (Schiff 1983, 23–51, Bernard 1995, Bernard 1988). In parallel with his mid-twentieth-century peers in Europe, for whom compositional form resulted from a process of transformation, Carter avoided predetermined forms in favor of forms that arose out of “constant growth and change” (Rosen 1984, 39).(1)This quote is included in Marguerite Boland’s introduction to Carter’s formal practices (2012, 80–85). Boulez ([1956] 1990) and Stockhausen (1963) were leaders in European developments in compositional form, speaking publicly about the topic, and analyzing and writing about form in Debussy and Webern. Responding to a question in 1960 about whether he tried to shape the free writing in his first string quartet into formal patterns, Carter emphasized, “since I consider form an integral part of serious music, I certainly did” ([1960] 1997, 219).

[ 2 ] Carter’s two primary compositional techniques for creating large-scale form involve temporal control: long-range polyrhythms and textural stratification. The first technique involves establishing a polyrhythmic framework in which concurrent pulses, often with complex relationships to each other, determine the length of the piece (Link 1994, Poudrier 2009, Mead 2012). First used in the Introduction and Coda to the Double Concerto for Harpsichord and Piano with Two Chamber Orchestras (1961), many subsequent compositions unfold within a large-scale scaffold – usually only intermittently audible – of two or more consistent pulses. In Carter’s one-movement Oboe Concerto (1987), for example, two pulses in the ratio 63:80 start in m. 2 and conclude in the last measure of the piece (Link 1994, 78–89; Mead 2012, 155–62).

[ 3 ] In the second technique, the texture is stratified into two or more streams – identifiable linear entities with characteristic musical behaviors that proceed simultaneously, weaving in and out of the listener’s attention.(2)One of the most discussed examples of distinctive musical layers in Carter’s music is his Second String Quartet, composed in 1959 (Bernard 1993, Koivisto 1996, Roeder 2012, 110–114). Writing about his music after 1950, Carter explained “There is no repetition, but a constant invention of new things – some closely related to each other, others, remotely. In both the Double Concerto and the Duo there is a stratification of sound, so that much of the time the listener can hear two different kinds of music, not always of equal prominence, occurring simultaneously. This kind of form and texture could be said to reflect the experience we often have of seeing something in different frames of reference at the same time.” (Carter 1977, 330)

[ 4 ] Carter’s polyphonic style is differentiated from that of his peers in part by his approach to the timbral identity of the streams that present these “different kinds of music”; rather than following traditional instrumental groupings, he often creates unexpected partners. In an early example, the instruments of his String Quartet No. 3 (1971) are paired into duos, one comprising the first violin and cello, the other the second violin and viola. The five quartets in Penthode (1985) all comprise unusual combinations of instruments; trumpet, trombone, harp and violin I form one group, while another consists of oboe, tuba, violin II and cello.

[ 5 ] These two techniques play an equally important role in Carter’s vocal writing, in conjunction with the influence exerted by the carefully chosen texts on musical form. His settings often reflect the formal structure of the poem, with, for example, instrumental interludes separating stanzaic or syntactic divisions in the text, as is the case in “Metamorphosis,” from In the Distances of Sleep (2006) (Ravenscroft 2012, 284–91). Carter employs polyrhythmic frameworks in many of his songs, including the last song in his cycle Of Challenge and Of Love (1994), where the sparse piano texture clearly reveals the steady presence of the polyrhythm controlling the large-scale rhythmic structure (Ravenscroft 2012, 278–84). In an earlier example, “Anaphora,” from A Mirror on Which to Dwell (1975), two consistent pulses in the ratio 65:69 create the song’s rhythmic framework (Schiff 1983, 1998, Weston, 1992, Zimmerman 1998, Ravenscroft 2003, Coulembier 2012).(3)All of these sources discuss Carter’s use of polyrhythm in “Anaphora” as well as analyzing other songs from the Mirror cycle. A steady cross pulse between the violin and piccolo in “Insomnia” (also from the Mirror cycle) help those instruments to coalesce into a single stream; in this case the polyrhythm plays a role in the stratification of the texture, serving to distinguish this stream from a second, rhythmically dissimilar stream comprising viola and marimba (Ravenscroft, 1999/2000).(4) Streams with contrasting musical behaviours also characterize other mid-period vocal works, including other songs from the Mirror cycle (Shreffler 1993); in Syringa (1978) Carter extends the concept of stratification by adding a second vocal layer in the form of the bass voice that comments in ancient Greek while the soprano sings the Ashbery text. As is most often the case in Carter’s songs, texture and text are intimately related: the textural streams represent contrasting characters in the text, with their musical behaviors portraying personal qualities suggested in the poem. In “Insomnia,” the registrally high, slowly unfolding cross-pulse stream represents the serene moon, while the agitated tremolos set in a much lower registral placement represent the sleepless, emotionally distraught speaker. Similarly, Carter’s practice of associating distinct, simultaneous continuities with particular characters informs much of Guy Capuzzo’s analysis of Carter’s opera What Next? (1997–98) (Capuzzo 2012).

[ 6 ] This essay is motivated by questions of difference. How does Carter approach form when setting a poem that doesn’t present clearcut characters? What role does textural stratification play, if any? How does he shape large-scale formal design without using a polyrhythmic framework? Carter’s late song cycle What are Years (2009) is a collection of five settings on poems by Marianne Moore. The opening song “Like a Bulwark” presents an example with which to examine these questions.

[ 7 ] Written in 1956, the poem “Like a Bulwark” demonstrates the features that characterize Moore’s mid-forties to mid-fifties “fable” years: “brevity, fine abstract distinctions, and two qualities which are only apparently contradictory – the cryptic and the didactic” (Holley 2009, 135–36).(5)The seemingly contrary element of Moore’s poetry from this period would undoubtedly have appealed to Carter, whose “well developed appreciation of irony, wit, and contradiction” is discussed by Ravenscroft (2012, 272). It comprises two five-line stanzas clearly indicated through typographical indentation and describes in matter-of-fact terms a “tempest-tossed” bulwark enduring the forceful pressures of assault from which, paradoxically, it derives its strength and is both “firmed” and “affirmed.”(6)The online Merriam-Webster dictionary defines “bulwark" as “1 a. a solid wall-like structure raised for defense: rampart; b. breakwater, seawall; 2. a strong support or protection; 3. the side of a ship above the upper deck” ("http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/bulwark," accessed 3 March 2016). Moore conveys the duress the bulwark undergoes through increasingly violent imagery (“thrust of the blast,” “lead saluted” – with Carter reinforcing the association with munitions by specifying that “lead” be pronounced “led”) and through the use of alliteration with stop-plosive consonants (“pent by power,” “paradox”) and sibilance (“tempest-tossed,” “compressed”). Ultimately, despite the adversity, the final image is one of triumph, describing the United States flag (“Old Glory”) as flying “at full mast.”

[ 8 ] While the poem – with its valuation of resilience and fortitude – can be read in this straightforward manner, its symbolic meaning is more enigmatic. The language of struggle and power combined with the victorious image of the American ensign hint at a political or military analogy, but the poem eludes a more direct interpretation.

[ 9 ] Unlike many of the poems set by Carter, “Bulwark” does not present clear characters, or even a first-person speaker. The bulwark is personified to some degree and attributed human qualities (“you take the blame”), but is never developed into a persona with associated behaviors. In particular, the absence of contrasting characters deprives Carter of a textual source on which to base his archetypical interacting contrapuntal streams with distinctive characteristics, and there are no overarching polyrhythms guiding the formal structure. Unusually for Carter, the form of the song is also not generated by the form of the poem. In place of an instrumental interlude (or some other musical signifier) indicating a break between the two stanzas, the music proceeds seamlessly across this moment of poetic structural division. Instead, Carter’s setting suggests a three-part formal structure, albeit asymmetrical, where the opening material returns at the end after a relatively long contrasting section.

[ 10 ] The large-scale ABA' shape of “Bulwark” is central to the listening experience of the song. Carter expresses the form on the musical surface through textural differentiation, making it readily apprehensible, even on a first hearing. Example 1 provides a highly simplified outline of the formal divisions and the textural features associated with each section. After opening with loud, sustained tutti chords, a transitionary passage leads to a dramatically lightened, linear texture, with soft staccato isolated notes embellishing the prominent vocal line. An accumulation of energy and increase in linear density leads to a local climax in mm. 19–21. After this, the contrapuntally conceived texture continues, although now at the higher level of rhythmic activity and intensity – until, in the final measures the stressed, tutti chordal texture resumes to close the piece in the same way as it started. Although, for convenience, the moment of return is identified in Example 1 as m. 31, where one hears the first sustained chord, the resumption of behaviors is part of a progression that starts earlier, as will be elaborated on in the discussion of section B.

Example 1

“Like a Bulwark” – Outline of Formal Structure

| A | transition | B (climax) | A' | |

| chordal | linear | chordal | ||

| mm. 1-6 | mm. 7-9 | B1: mm. 10-21 | B2: mm. 21-31 | mm. 31-33 | sustained accented chords |

intermittent staccato isolated pitches |

intermittent staccato gestures |

accented chords |

[ 11 ] Carter’s use of contrasting texture to shape large-scale formal designs characterized by return can be found in other late works. In her analysis of the ASKO Concerto (2000) and Boston Concerto (2002), both of which feature ritornello form, Marguerite Boland points out that Carter takes the same approach in the two works, whereby “concertinos consist of a counterpoint of melodic lines while the ritornellos continually return to widely spaced tutti chords” (2012, 95–96).

[ 12 ] In order to discuss the ways in which Carter effects a sense of return, the opening of the song needs to be examined closely. Early in his career the composer stressed the importance of establishing “a field of operation with its principles of motion and of interaction” at the beginning of a work ([1960] 1997, 218), a compositional tenet he maintained throughout his long career. For example, his String Quartet No. 2 from 1959 begins with each instrument laying out the repertoires with which it is associated – intervals, articulation, rhythm and tempo – while Changes for guitar (1983), written over 20 years later, starts with a measure whose influence can be traced throughout the rest of the composition (Capuzzo 2000, 41–48).

[ 13 ] “Bulwark” opens with the full ensemble presenting a powerful block of sound, spanning a wide, but relatively low, register and suggesting the immovable monolithic structure of its title, the bulwark. The wall of sound is not static, however, and is animated by accented chords that pulse heavily and repeatedly, while the voice presents its opening phrases in a jagged, disjunct line.(7)The soprano’s highest pitch, A♭5, is the highest pitch of the opening measures, giving the passage its darker (lower) registral color. Carter creates a sense of immobility through the use of two fixed pitch/register schemes, which divide the chromatic aggregate into two hexachords, shown below in Example 2.(8)Fixed pitch/register schemes are used in other Carter songs, for example “Anaphora” from A Mirror on Which to Dwell, and “End of a Chapter” from Of Challenge and Of Love. Winds and strings, excluding the second violins from m. 2 to m. 5, articulate pitch set {B1, A2, G♭3, C4, D♭4, E♭4}, a member of sc 023469, while the harp, soprano and second violins (as of m. 2) combine in a presentation of its literal complement, {F4, G4, B♭4, D5, E5, A♭5}, a member of 023469’s Z-related partner, sc 023568. In the ensuing analysis I will refer to 023568 as hex A and 023469 as hex B.

Example 2

Elliott Carter, “Like a Bulwark,” fixed pitch/register schemes in mm. 2–5

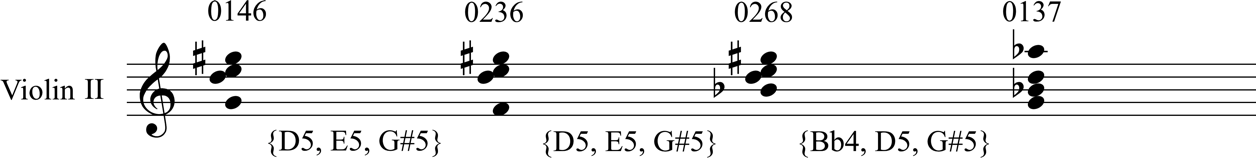

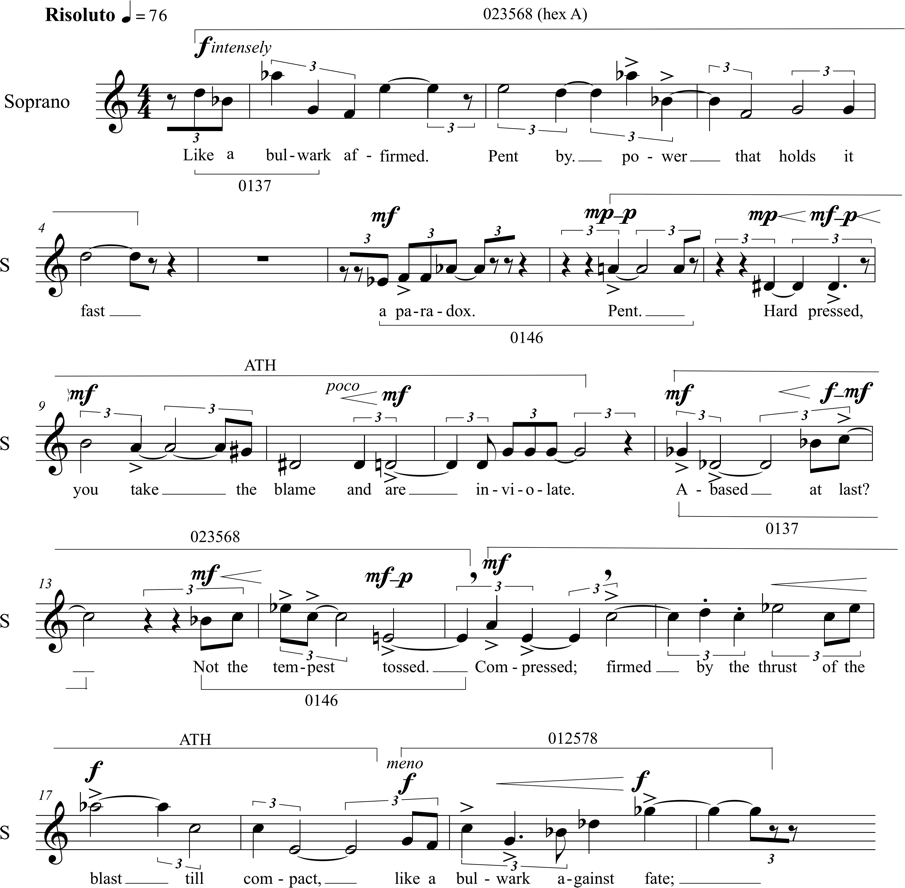

[ 14 ] Carter’s late music is characterized by a greater economy of harmonic material than his earlier compositions, particularly his focus on the all-interval tetrachords (AITs) 0137 and 0146, and the all-trichord hexachord (ATH) 012478. At first it may seem surprising that these “signature sets” (Capuzzo 2012, 29) are not explicitly featured in the formative measures of the opening song of the cycle, particularly since they do play as prominent a role in the song as one might expect of a late Carter work. However, like the ATH, hex A contains 0137 and 0146 as tetrachordal subsets, and hence the hexachords are structurally linked, at least in theory.(9)This property is not unique; a further sixteen hexachords share the same subset property with the ATH. Carter makes the theoretical potential a reality as soon as the voice enters in m. 2 and the second violins switch from participating in hex B to working with the voice and harp in their presentation of hex A. Example 3a excerpts these three instruments. In the voice, the eponymous opening phrase – “Like a bulwark” – is articulated by an angular linear statement of 0137, highlighting this subset before the soprano presents the other pcs that complete hex A, while the first divisi chord in the second violins is a statement of 0146.(10)When he set the poem to music, Carter also set the title as part of the first line of the poem, clarifying Moore’s opening single word “affirmed.” A similar practice can be observed in “O Breath” from A Mirror on Which to Dwell.

Example 3a

Elliott Carter, “Like a Bulwark,” set-class structure in soprano, violin II and harp, mm. 2–6

[ 15 ] Over the next few measures, mm. 2–5, the second violins state another three hex A chords before switching back to their original role and being reabsorbed into the larger orchestral statement of hex B. This four-chord passage, reproduced in Example 3b, is worthy of closer examination, not only because it clarifies Carter’s deliberate emphasis of the hexachord’s AIT subsets, but also because it extends the process of “morphing,” first identified as such by Boland. Describing how Carter creates “harmonic flow,” she defines morphing as “a series of gestures characterized by chains of pitch and interval invariance [that] morph into and out of ATH harmonies” (Boland 2006). While Boland’s focus is on the ATH, a signature set in the piece she is analyzing (Carter’s Con Leggerrezza Pensosa), the concept adapts itself readily to other featured set classes. In this “Bulwark” passage, Carter moves incrementally from one AIT (0146) to the other (0137) through two intermediary steps, concluding with the same tetrachord with which the soprano started three measures earlier.(11)This instance of morphing differs from those discussed by Boland not only by chord type, but also texturally; rather than common pitches being presented linearly in different instruments (see Example 7 on p. 42), here they are reiterated through the violin’s repeated chords. As can be seen in Example 3b, three of the four pitches are held invariant between each successive chord statement, {D5, E5, G♯5} between the first three chords, and {B♭4, D5, G♯5/A♭5} between the last two chords. In other words, rather than transforming in and out of a single focus set class, here one AIT morphs into the other.

Example 3b

Elliott Carter, “Like a Bulwark,” morphing in violin II chords, mm. 2–5

[ 16 ] These subtle changes in the second violins’ chords do not detract from the listener’s overall impression that the instruments are providing a canvas over which the soprano paints a verbal image.(12)Identifying Carter’s “unswerving focus on the vocal line” as a characteristic of Carter’s songs since his return to vocal writing in 1975, John Link discusses how Carter’s “first-person lyric perspective” takes form in A Mirror on Which to Dwell, Syringa, and In Sleep, In Thunder (2012, 36–38). The harp does little to alter that perspective. Coordinated rhythmically with the second violins, it repeats a pentachordal subset of hex A, {F4, B♭4, D5, E5, A♭5}, a member of sc 02368 (further reduced to a tetrachord in m.3), as can be seen in Example 3a. In m. 5 the “missing” note, pc 7 (G4), is added, enabling the harp to articulate a complete version of hex A, but without a discernable change to the textural/spatial environment that has been established.

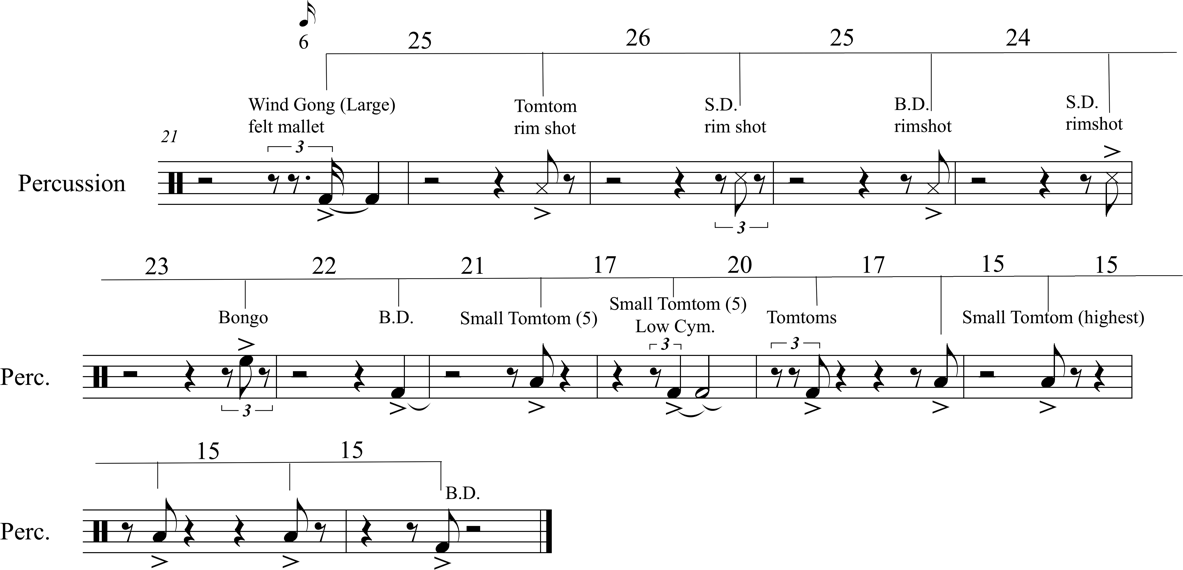

[ 17 ] While the pitch/registral milieu of the opening is stable, it is far from motionless, and the listener is immediately struck by the pulsating rhythm of the orchestral chords, which seems to suggest the regularity of waves pounding against the bulwark. The wind and string chords, cooperating in their presentation of hex B, are joined by a variety of percussion instruments as they articulate an attack every seventh eighth note, presenting a speed of MM 21.7 within the overall tempo of quarter note = 76. The seven attacks that comprise the pulse are shown in Example 4.

Example 4

Elliott Carter, “Like a Bulwark,” hex B pulse, mm. 1–6

© Copyright 2009 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

[ 18 ] In summary, the important features of the opening passage are as follows: chordal texture, steady pulse, low registral range, spatially fixed pitches, limited hexachordal harmonic vocabulary, AIT subsets, chromatic aggregate, disjunct vocal line, loud dynamics. As one might expect, these elements constitute Carter’s “field of operation,” whose potential will subsequently be explored. In “Bulwark” this exploration serves two goals: to articulate the song’s ternary formal design, and to create the sense of continuity and coherence necessary for the integrity of the work. As we shall see, Carter assigns specific elements to each purpose.

[ 19 ] Most immediately, following the expository measures, the composer needs to establish the distinction of these opening materials by emphasizing contrast, in order to create a sense of return at the end of the song. Carter’s well-documented use of contrasting musical materials is most often associated with his contrapuntal textures, as a means of aurally distinguishing simultaneous streams, but here the contrast is about succession rather than simultaneity. It is not, however, abrupt. The transitional passage that follows the opening six measures, the first measure of which is reproduced in Example 5a, plays a critical role in setting up the opposing musical behaviors while also serving a linking function.(13)This example corrects an error in the second violin and cello parts of the printed score, where rests on the downbeat of the second quarter note are notated as triplet eighths instead of triplet sixteenths.

Example 5a

Elliott Carter, “Like a Bulwark,” transition from sections A to B, mm. 6–7

© Copyright 2009 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

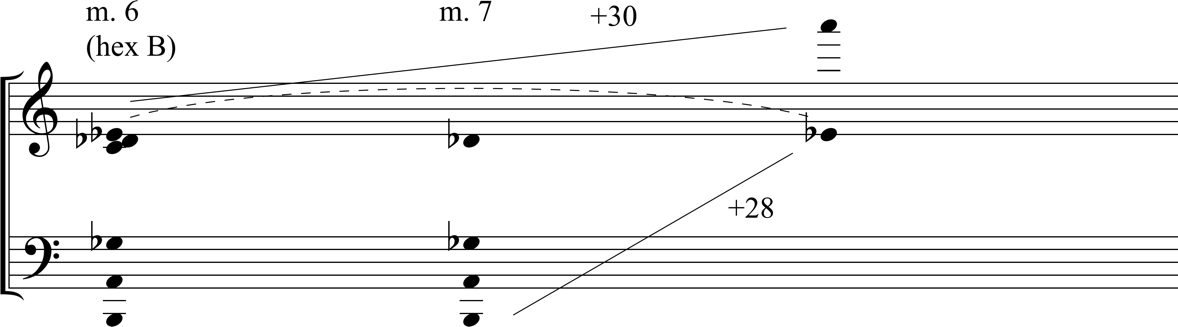

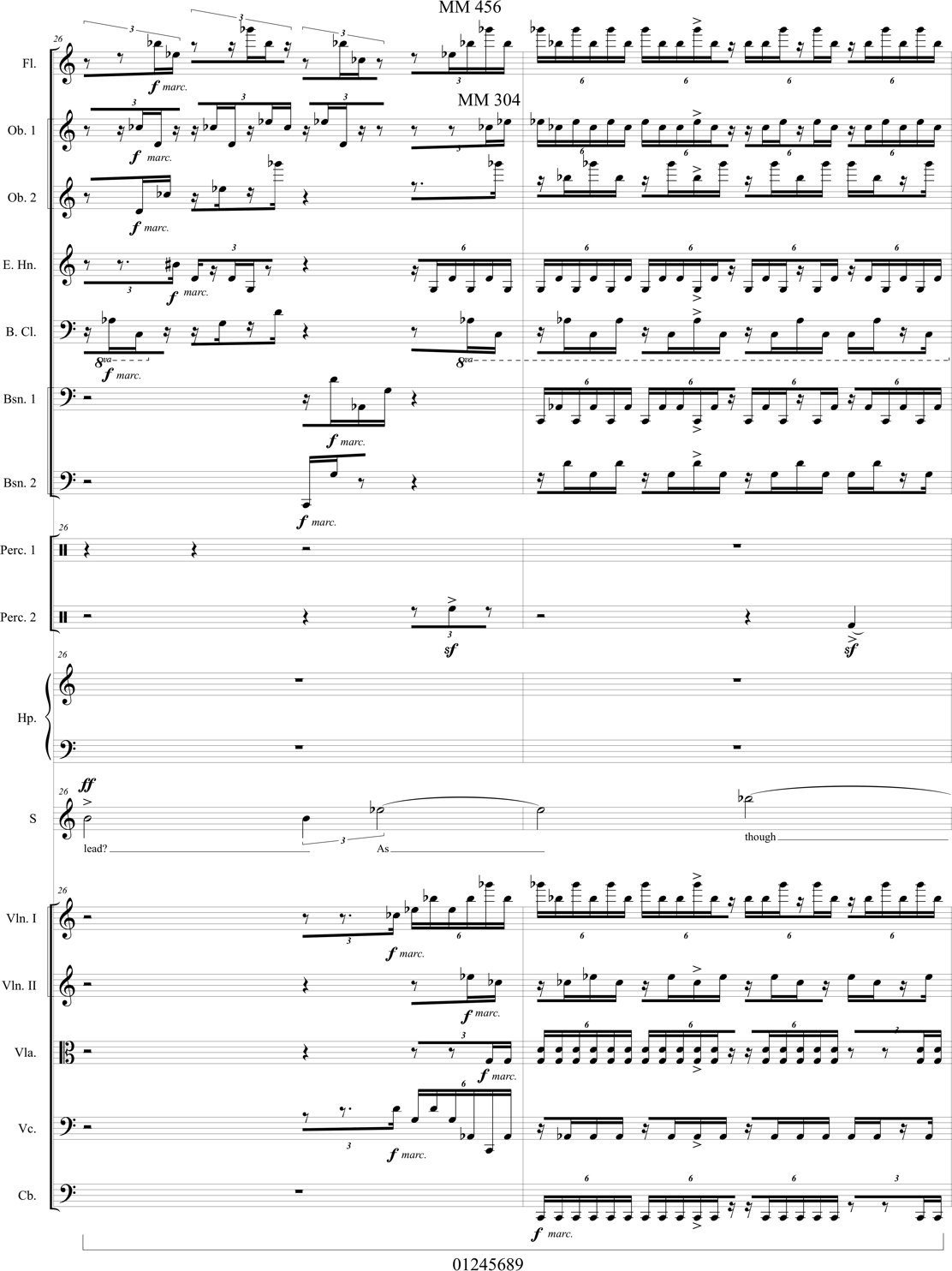

[ 20 ] Rhythmic activation is the first change to strike the listener’s ear, as the evenly spaced, sustained chords of the opening are replaced by sixteenth notes in m. 7 (articulating a speed of MM 304), followed shortly by sextuplet sixteenths later in the bar (MM 456).(14)The rhythmic coordination between the instruments as they articulate the sixteenth-note subdivisions of the first beat in m. 7 might at first suggest that the sustained chords of before have simply sped up; this impression is soon discharged once the rhythmic activity becomes more varied between the instruments later in the bar. Although these rhythmic gestures are very short-lived and do not persist past m. 7, they are significant. Not only do they effectively create contrast here, but they also foreshadow the speeds that characterize the passage that leads to the return of the opening materials at the end of the song (discussed later in the analysis).

[ 21 ] By the end of m. 7 a second feature of contrast is evident: as shown in Example 5b, the registral range of m. 6 (hex B) has shifted dramatically upwards by about two-and-a-half octaves, with the highest instrumental pitch, E♭4, now serving as the lowest pitch.

Example 5b

Elliott Carter, “Like a Bulwark,” registral shift, mm. 6–7

[ 22 ] Carter, however, has always been concerned with “the flow of music,” and how single moments relate both to their past and their future (Edwards 1971, 98).(15)Boland draws on this concept in her definition of “linking gestures,” which “contain some pitch and interval material that has just been heard, as well as some material that is about to be heard in the next event or texture” (2006, 35). If we revisit the opening of m. 7 in Example 5a, we can see how the contrast in rhythmic figuration is balanced by aspects of continuity. Most notable is the initial preservation of pitch: the first pitch collection in m. 7 (occurring on the second sixteenth note of beat one) is a subset of the spatially fixed hex B collection of m. 6 – {B1, A2, G♭3, D♭4} – and the registrally prominent E♭4 of m. 6 continues to be aurally salient as the highest pitch on the fourth sixteenth of the first beat. The distinctive pitch profile of the intervening (third) sixteenth note collection serves to highlight a rhythmic connection: this accented chord falls seven eighth notes after the last sustained chordal attack, thereby extending the MM 21.7 pulse into the transition.

[ 23 ] By the end of this short transition, the changes in the instrumental ensemble’s pitch and rhythmic behaviors have effected a transformation into a contrasting B section. As can be seen in the columns labeled A and B in Example 6, many of the elements comprising Carter’s “field of operation” have been harnessed in service of this formal goal, either because their behavior would now be considered the opposite of the prior behavior (e.g. low vs. high register) or because a feature is now absent (e.g. concern with the chromatic aggregate vs. no focus on the aggregate). In fact, the only features from those originally identified that do not play a role in articulating contrast are the prominent AIT subsets and the characteristically disjunct vocal line; instead, Carter uses these elements to weave elements of consistency throughout the song, as will be discussed later.

Example 6

| Elements | A | B | A' |

| Texture | chordal: sustained accented chords |

linear: intermittent staccato isolated pitches and brief tremolos | chordal: accented chords |

| Rhythm | steady pulse | free, accelerandos | steady pulse |

| Register | low | high | low |

| Pitch | spatially fixed pitches | free pitch placement | free pitch placement |

| limited hexachordal vocabulary | no focus on hexachords | limited hexachordal vocabulary | |

| chromatic aggregate | no focus on aggregate | no focus on aggregate | |

| Dynamics | loud | soft | loud |

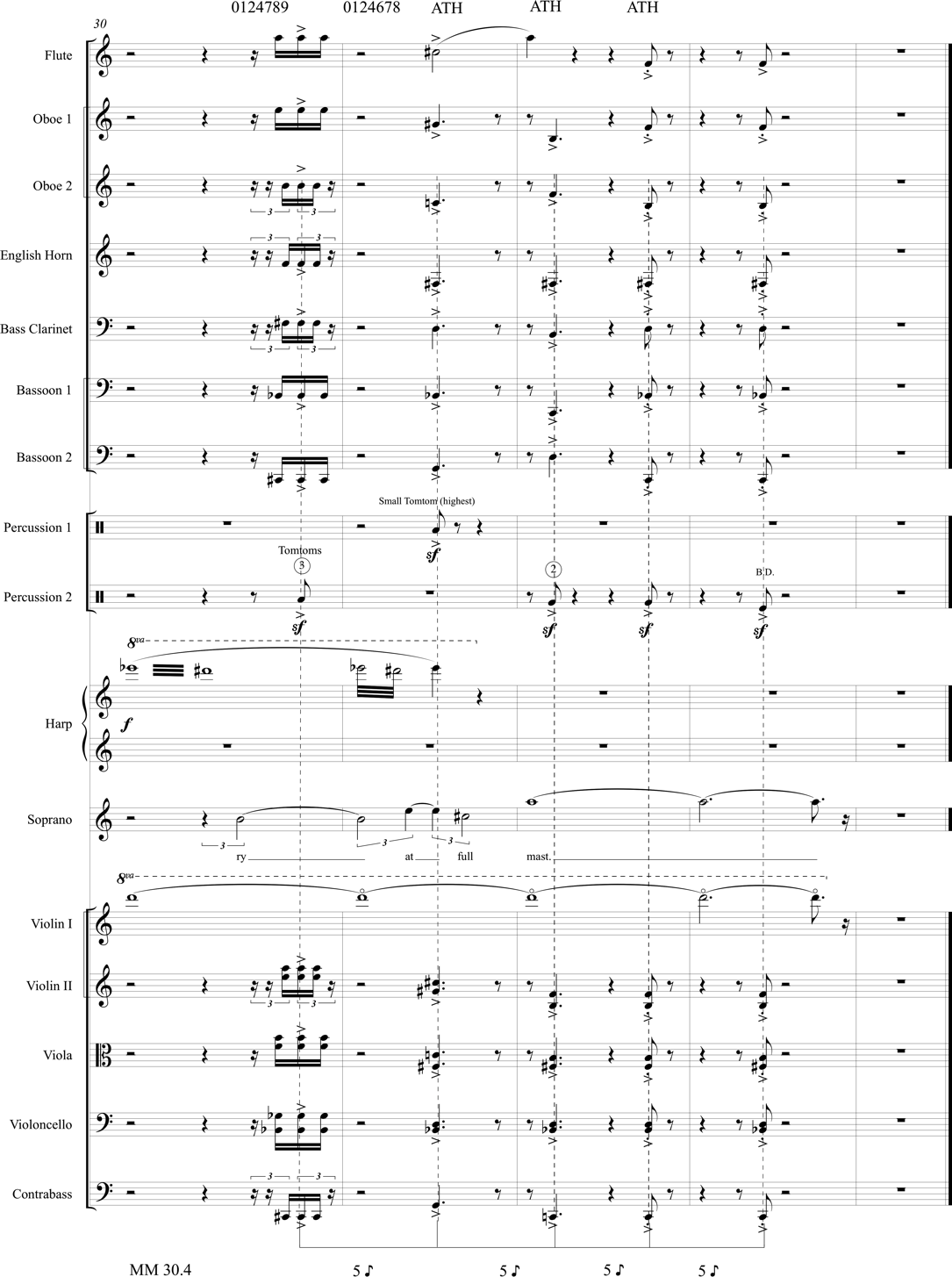

[ 24 ] With the expository musical elements so emphatically established – and reinforced by the clear contrast at the start of the B section – Carter has little difficulty in creating a sense of return at the end of the song by resuming many of the opening musical behaviors. Example 7 shows how the chordal texture returns for the first time since the beginning of “Bulwark” with similar doubling between winds and strings, although now with some rhythmic variation. Accented tutti chords are articulated first through repeated sixteenth notes in m. 30, then as two sustained sonorities, and, finally, as two staccato chords. More important than the duration of each chord is their spacing: separated by five eighth notes, they present a steady speed of MM 30.4, recalling the regularity of the pulsing chords at the slower opening speed of MM 21.7 and contrasting with the intervening rhythmic activity.(16)Although the start of section B was generalized in Example 1 as starting in m. 31 with the first sustained chord, the participation of the m. 30 sixteenth-note chord in the pulse arguably makes it part of the return. There is, in fact, no single point of articulation between sections B and A1. This early pulse attack mirrors the late pulse attack that occurs in m. 7 of the transition from sections A to B.

Example 7

Elliott Carter, “Like a Bulwark,” return of texture and pulse in mm. 30–33

© Copyright 2009 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

[ 25 ] The registral range of this closing passage is once again relatively low (other than the sustained harmonic in violin I) and shares two features in common with the opening. First, the soprano dictates the highest pitch in the passage (A5), and, second, the final chord (repeated thrice) has a very similar range to that of hex B, with C2 being the lowest pitch and F4 the highest, compared to B1 and E♭4 in hex B. Similar to the opening, the harmonic vocabulary in these closing measures is both limited and focused on the hexachord, this time the ATH (which shares AIT subsets with hex A). The septachords in mm. 30 and 31 contain the ATH as a subset while the last three chords reiterate a single ATH with some minor voice exchanges.(17)Other pitch features such as spatially fixed pitches and the chromatic aggregate are not evident here. Finally, the song ends as it began, with high dynamic levels, which, together with the steady pulse and accented tutti chords help to express an unequivocal assertion of power, depicting musically the enduring image of “Old Glory flying full mast.” These elements of return are summarized in the last column in Example 6.

— ◊ —

[ 26 ] Having examined the ways in which Carter establishes the large-scale formal shape of departure and return in “Bulwark,” we turn our attention now to section B, which, by virtue of its length alone, is essentially the body of the song. I have characterized B, mm. 10–31, as “contrasting” in comparison to the brief sections that bookend it, but, unsurprisingly, it is far more complex and dynamic than that adjective would suggest. Two large-scale processes unfold to shape this section, the first corresponding to section B1 in Example 1 and the second to B2. The discussion will initially focus on the ways in which Carter creates the mid-point climax in mm. 19–21, before turning to the processes that lead to the resumption of the chordal texture at the end of the song. In both cases, rhythm plays a fundamental structural role.

[ 27 ] Many of Carter’s rhythmic techniques serve to create a sense of regularity in the absence of a steady or discernable meter reinforced by rhythmic figuration. This is certainly true of his use of pulses, whether a single pulse or, more commonly, a cross-pulse formed by two or more simultaneous pulses. However, Carter’s toolbox of rhythmic techniques includes not only steady pulses and polyrhythms, but also speeds that accelerate or decelerate over time – and in “Bulwark” his focus is on creating temporal trajectories through two long-range accelerandos. As early as 1955, Carter started experimenting with this approach, explaining “in the course of exploring metric modulation, the idea of dealing with accelerandos and ritardandos intrigued me” ([1976] 1997, 273–74).(18)Here the composer’s focus is more on his notational solution to acceleration and deceleration than their expressive effect. The same rhythmic devices are features in Carter’s Double Concerto, where the solo instruments and orchestra contribute individual attacks that combine to form a long-range accelerando, and, later, ritardando (Bernard 1990, 188–96). In the fourth movement of his Variations for Orchestra from that year, a notated ritardando decelerates incrementally from beginning to end, while the sixth variation handles a large-scale accelerando in the same way. In his vocal works, Carter often uses acceleration to depict aspects of the text, for example, the accelerating perfect 5ths in “In Genesis” from In Sleep, In Thunder, portraying the fall from innocence (Sallmen 2007), or the steadily decreasing distance between oboe attacks in “Sandpiper,” which symbolizes the bird’s increasingly frantic movements (Ravenscroft 2003, 263–66).

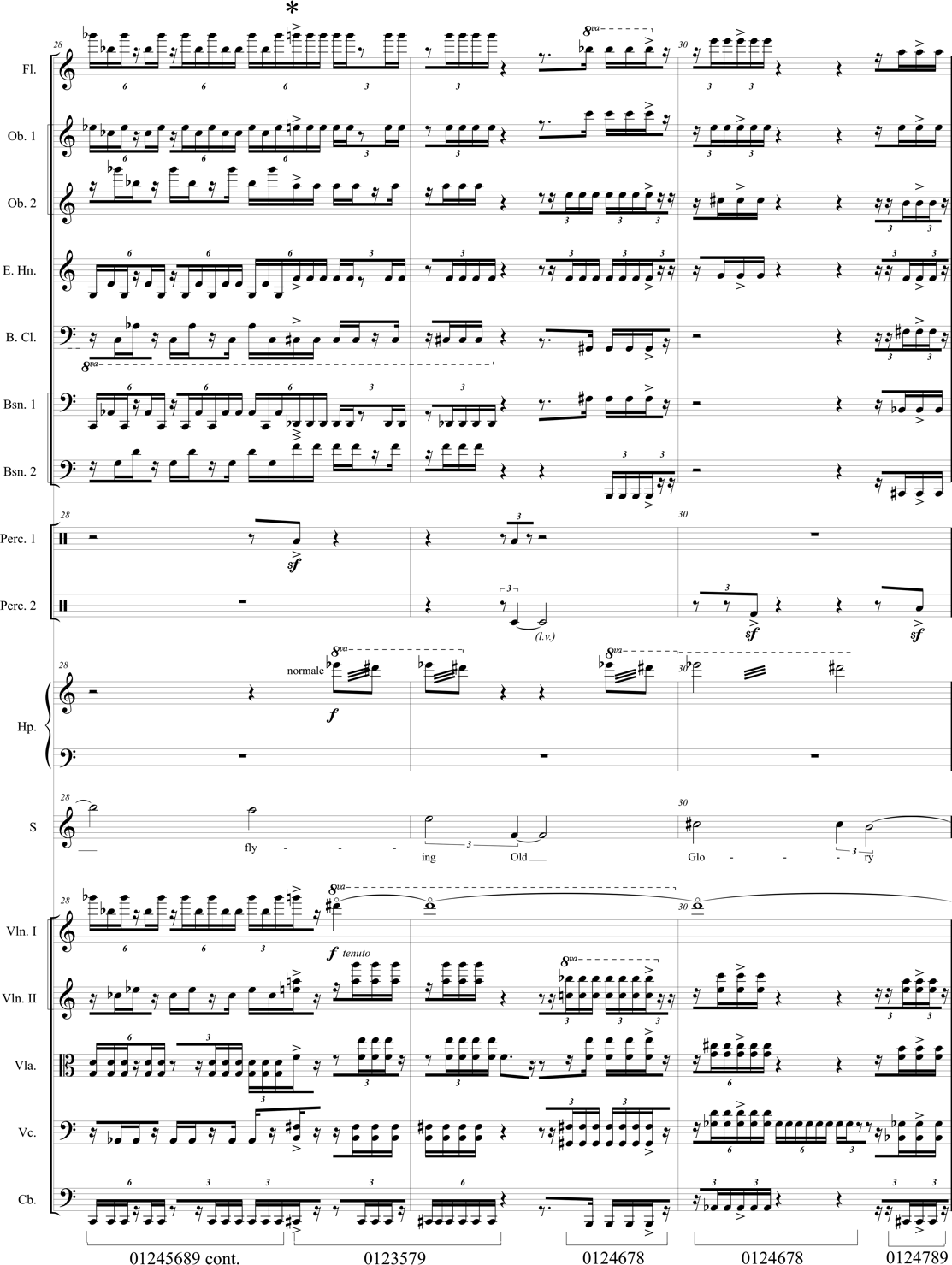

[ 28 ] Carter’s interest in “Bulwark” appears to be using accelerandos to guide the formal process more than depicting the meaning of the text. The first acceleration of section B governs a process of growing intensity that leads to a climactic passage in mm. 19–21, which sets the clarifying phrase, “like a bulwark against fate.” While it is true that the culmination of the accelerando at the beginning of m. 19 coincides with the word “blast” (“Compressed; firmed by the thrust of the blast”), the relatively superficial word painting here seems secondary to the accelerando’s role in deftly demarcating the midpoint of section B, and setting up the second half where increased levels of activity eventually segue into the reestablishment of the musical behaviours that characterized the opening of the song.

[ 29 ] The harp is assigned the role of presenting the acceleration in mm. 10 –19, each attack initially doubled in both rhythm and pitch by violin II. To ensure audibility, Carter indicates that the harp is to be played consistently louder than the sparse softer attacks in other instruments (“ sempre, ben marc.”), and attacks in both instruments are accented. Measured in multiples of the sextuplet sixteenth notes, the distance between attacks decreases from 20 to 19 before stalling on 18 in mm. 12–14, as shown in Example 8.

sempre, ben marc.”), and attacks in both instruments are accented. Measured in multiples of the sextuplet sixteenth notes, the distance between attacks decreases from 20 to 19 before stalling on 18 in mm. 12–14, as shown in Example 8.

Example 8

Elliott Carter, “Like a Bulwark,” accelerando, mm. 10–19

[ 30 ] At this point a curious overlap occurs as the timbre of the pulse is transformed. Before the harp/violin II attack occurs for the fourth time at 18 sextuplet sixteenths in m. 14, another harp attack enters prematurely 11 sextuplet sixteenth notes after the previous attack, this time doubled by the B♭ bass clarinet. A second harp/bass clarinet attack occurs 16 sextuplet sixteenth notes later in m. 15, and now the acceleration continues with harp/bass clarinet attacks occurring at ever-decreasing distances. The second violins stop participating in the accelerando and rejoin the other strings, presenting brief tremolos and isolated pitches.

[ 31 ] As the intensity builds, with isolated staccato pitches in the winds becoming short two- and three-note gestures and dynamic levels increasing, the accelerando thickens and expands its timbral colour. Halfway through m. 17 tom-tom attacks start to double the harp rhythmically – replaced by bongos in mid-m. 18 – and at the start of m. 18 the violas join in too, doubling the harp in pitch and rhythm. The accelerando culminates with a loud five-note harp gesture in accented triplet eighth notes, doubled by bongos and violas, that briefly articulates a steady speed of MM 228. The gesture is reinforced rhythmically by all of the wind instruments, with the first oboe doubling the harp in pitch as well.

[ 32 ] The discussion so far has focused on the ways in which the instrumental ensemble articulates Carter’s formal design for “Bulwark,” with little attention paid to the voice other than in the opening measures where the soprano, harp and violin II work together in their presentation of hex A. It is important, however, to recognize the way in which the soprano contributes to a sense of pitch continuity across the formal sections and to examine its behavior in the mid-section climax.

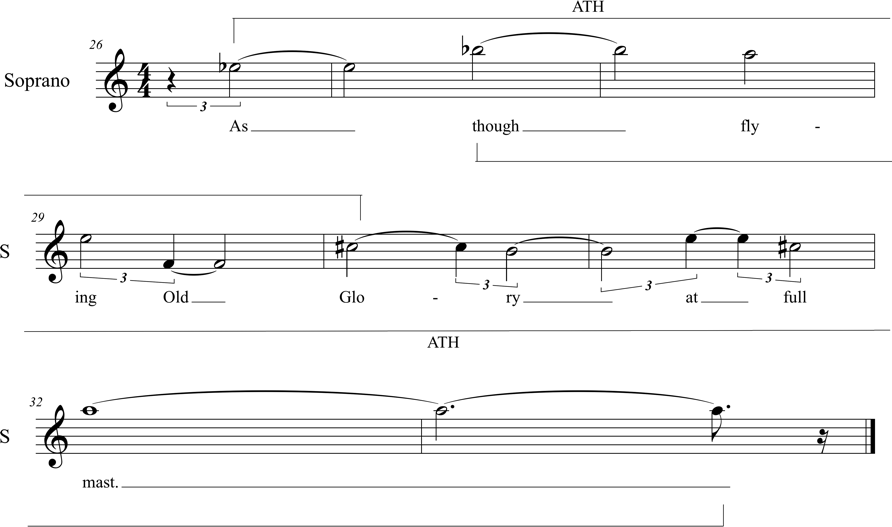

[ 33 ] As was mentioned earlier, the disjunct profile of the voice and its focus on the AIT and ATH – identified in the soprano in mm. 2–6 – remain unchanged across the song’s texturally and rhythmically contrasting formal sections. Example 9, which reproduces the soprano part from the opening to m. 22, shows Carter’s practice of separating textual phrases with rests, with most phrases acting as independent musical units articulating important set classes. For example, the phrase “Compressed; firmed by the thrust of the blast till compact” articulates the ATH. The question “Abased at last?” presents the AIT 0137, and its response, “Not the tempest tossed,” its companion 0146. Together they form sc 023568 in a transposition of hex A. Occasionally a phrase is presented as an independent musical unit – for instance, “a paradox” in m. 8 is surrounded by rests – but does not complete the set class. In this case pc 9, which completes the AIT 0146, occurs in m. 9 on the word “Pent”; this pc serves a double function, also initiating a statement of the ATH.

Example 9

Elliott Carter, “Like a Bulwark,” set classes structure in soprano, mm. 2–22

[ 34 ] Unexpectedly, the pitch classes that render the climactic phrase “like a bulwark against fate” (mm. 20–21) form a statement of sc 012578 rather than the anticipated ATH 012478. Why? Is this a notational error on Carter’s part, with pc 10 inadvertently replacing the required pc 9? Or is this an example of Carter’s sly sense of humor, his penchant for subverting the listener’s expectations, perhaps picking up on the idea of “paradox” from earlier in the poem?(19)Similar musical “jokes” abound in Carter’s works. For example, in “End of a Chapter” the expected final attack of the established pulse in the vocal part is omitted, replaced by silence; shortly afterwards the voice enters with the word “absence.”

[ 35 ] The second large-scale accelerando of section B starts shortly after the culminating phrase at the end of m. 21, and continues throughout B2, ending in m. 31 when it stabilizes into the steady pulse of the final measures. This time it is articulated by the percussion group, with accented attacks being presented by a range of percussion instruments, without any discernable timbral pattern. As with the previous accelerando, the distance between attacks can be measured in sextuplet sixteenth notes. Example 10 shows how, after a minor hiccup where the distance increases from 25 to 26 sextuplet sixteenths, and another brief anomaly in mm. 29–30, a steady decrease occurs until m. 31, where the pulse of attacks separated by 15 sextuplet sixteenth notes (or, more simply, five eighth notes) is established.

Example 10

Elliott Carter, “Like a Bulwark,” accelerando, mm. 21–33

[ 36 ] Against this steadily accelerating rhythmic framework, the linear instrumental texture continues in a similar fashion to before, but now at a higher level of activation than in section B1. Instead of isolated pitches or dyads, the wind and string instruments have more extended staccato gestures, and the dynamic levels are significantly higher. The vocal line, on the other hand, stretches out with longer sustained note values, distinguishing itself from the increasingly frenetic activity that surrounds it.

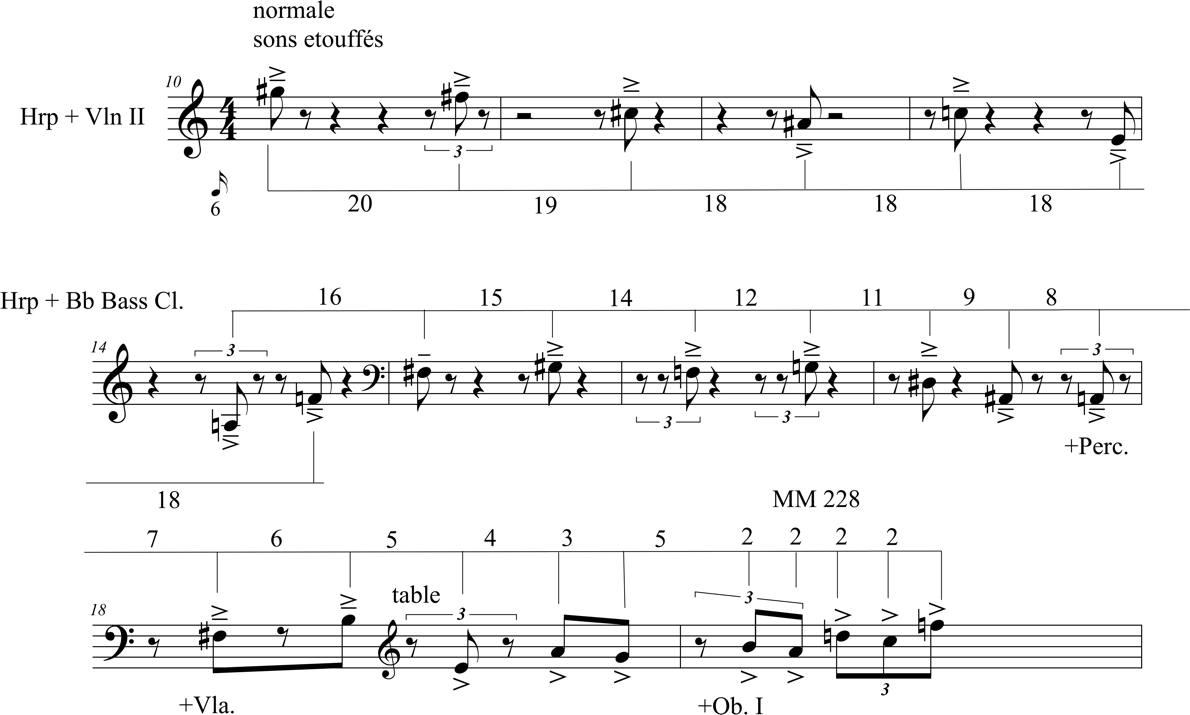

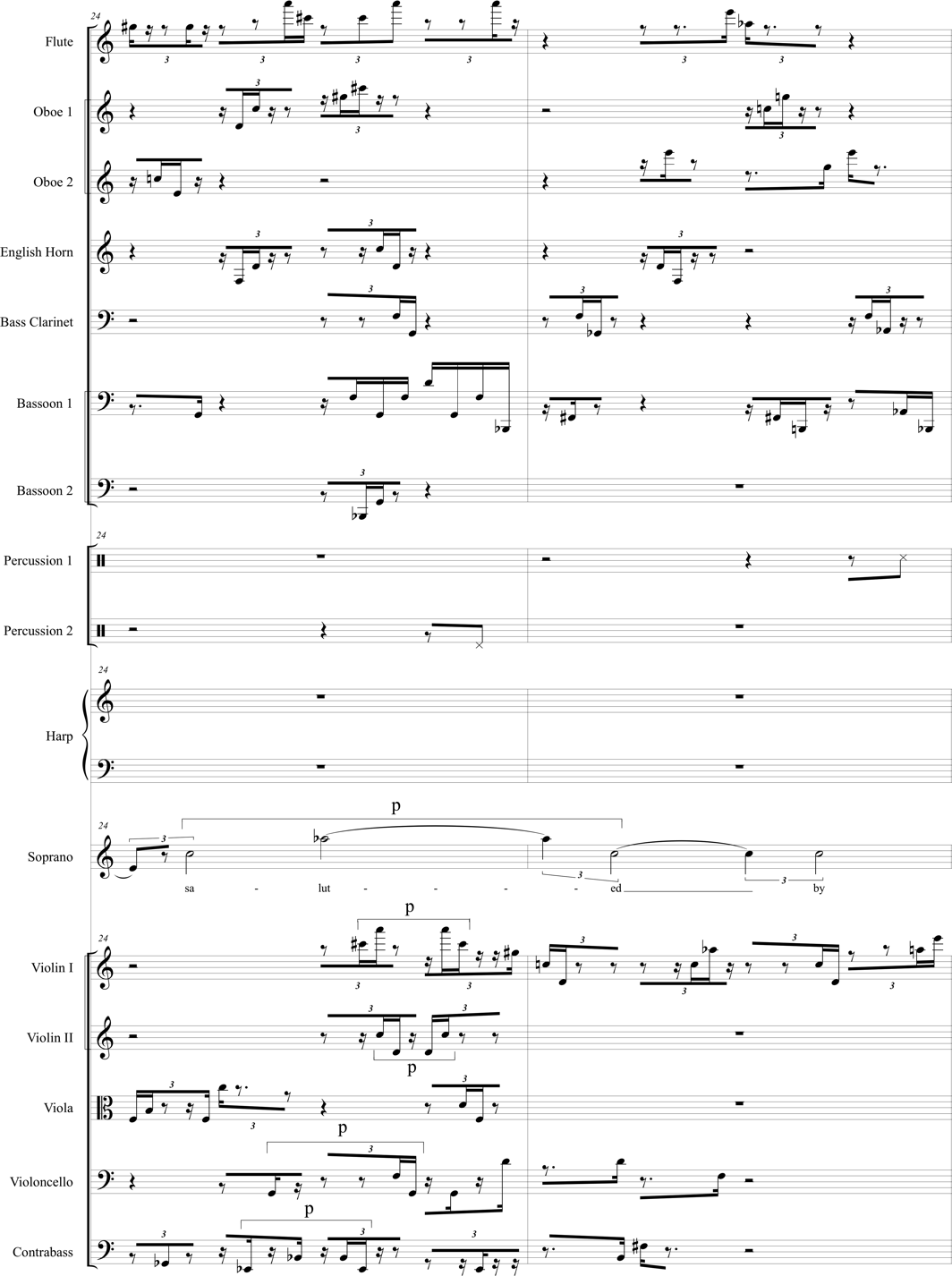

[ 37 ] Unlike the relatively fast shift from A to B, Carter takes a different approach to the transition back to A material at the end of the song. Here, the process occurs more gradually and in a staggered fashion, making the identification of a transitionary section challenging and a clearcut moment of return equally so. Example 11a shows how the intermittent gestures that characterize section B2 (seen for example in mm. 24–25) coalesce as of mm. 26–27.(20)An example of word painting can be seen in m. 24 where Carter reflects the almost palindromic play on words (“lead saluted, saluted by lead”) with a series of brief symmetrical pitch gestures, bracketed and marked “P” in Example 11a. See for example the strings, beats two to four, and the vocal setting of “saluted.” The palindromic gestures are more extended in m. 22, leading up to and accompanying the first statement of “lead” (not shown). The instruments lose their textural and rhythmic independence, articulating the two constant speeds – MM 304 (sixteenth notes) and MM 456 (sextuplet sixteenths) – that were introduced in m. 7. An accented mid-measure attack by winds and strings in m. 28 (indicated by an asterisk in Example 11a) reinforces the accelerando attack in the percussion, presaging the final section where, starting on the last beat m. 30, the entire ensemble participates in the pulse (shown earlier in Example 7), which proceeds at MM 30.4, one-tenth the rate of the constant sixteenth-note speed.(21)In a typically Carteresque off-kilter moment, there is a near miss on first beat of m. 30 where an accented instrumental attack enters prematurely, one sextuplet sixteenth earlier than the accelerando attack in tom-toms.

Example 11a

Elliott Carter, “Like a Bulwark,” transition from B to A1, mm. 24–30

© Copyright 2009 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

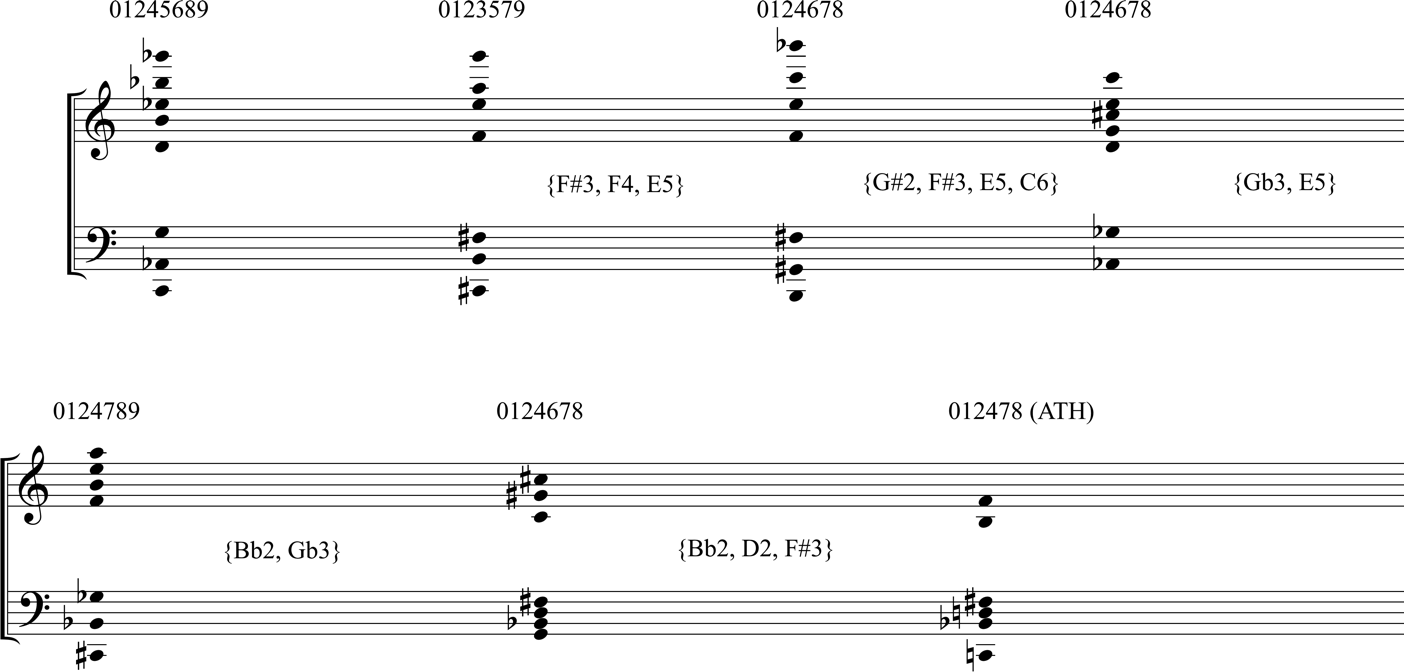

[ 38 ] In addition to their rhythmic compatibility, as of m. 26 the winds and strings double each other in pitch. Together they present a series of seven- and eight-member set classes, identified below the staff in Example 11a, that circle around the ATH before finally stating it explicitly in m. 32.(22)Carter’s treatment of signature sets in this way was established early in his compositional career. Explaining the role of the AIT in his First String Quartet (1951), for example, he states that one of the ways in which a “key chord” can “function… as a formative factor” (in addition to being used in significant points in the music), is by being presented with “the number of notes… increased and diminished in it...” (Carter [1960] 1997, 219). Jonathan W. Bernard discusses pentachordal “supersets” as a way of analyzing passages where the AIT is not explicitly present to show that it is nonetheless contributing to the sense of coherence and continuity in the music (Bernard 1993, 244–45). Starting at the end of m. 28, Carter excludes the first violins from participation; instead they double the harp with a high D♯7 harmonic. (Set classes are labeled above the staff in Example 11b.) Embryonic forms of the ATH are embedded in each chord in mm. 26–32, as can be seen in the winds/strings chord reduction in Example 11b. The first two chords contain the pentachordal ATH subset sc 01248, while the subsequent four septachords act as supersets, embracing the full ATH with one additional pitch.

Example 11b

Elliott Carter, “Like a Bulwark,” set-class structure in winds/strings, mm. 26–32

[ 39 ] The sense of coherence engendered by these ATH-like chords is amplified by voice-leading continuity. Despite the dramatic reduction in registral range as the upper register falls to a similar low level as the opening, Carter preserves two, three or four pitches between each successive chord (indicated between the two staves in Example 11b). Continuity evolves into stability and reprise in the last few measures, with the establishment of the steady rhythmic pulse, and the emergence of the unadorned ATH in the winds and strings. The soprano reinforces the primacy of the ATH as a key chord in A1 by closing with overlapping statements of 012478, as shown in Example 12.

Example 12

Elliott Carter, “Like a Bulwark,” set-class structure in soprano, mm. 26–33

[ 40 ] This essay has used “Like a Bulwark” to present a response to the questions posed in the introduction about Carter’s approach to formal design. There are, of course, many more aspects of the song to explore; Carter’s use of the music to portray the meaning of the text has only been lightly touched upon, for example, and the pitch structure of the vocal line, with its attention to particular pitch intervals such as the perfect fourth, invites closer examination. But we have a better sense now of how Carter creates an overarching ternary structure in the song, how gradual process is as important as sudden contrast in shaping form, how short-lived pulses and accelerandos can substitute for long-range polyrhythms, how he uses textural differentiation sequentially as well as to distinguish individual strata, and the role that pitch structure plays in both large-scale continuity and in moment-to-moment progression. Although Carter had already established these compositional techniques much earlier – as I illuminated in my opening discussion – the fluid way in which this mature work integrates elements of the techniques rather than adopting them systematically suggests a composer whose fluency in the grammar and vocabulary of his style enabled him to draw on them freely in service of meeting his expressive goals.

[ 41 ] In 2008, as his 100th birthday approached, Carter stated with characteristically deceptive simplicity, “every piece has to be an adventure, it has to be a new answer to the question of how you make a convincing musical form” (Hewett 2008). In this essay we have followed Carter’s footsteps to discover his exploration of form in “Like a Bulwark.” But the nature of adventure means that no two expeditions are the same – and many more of Carter’s journeys remain to be revealed, not only in the remaining four songs of What are Years, but in the cluster of vocal compositions that the composer gifted to us in his final years.

Footnotes

1. This quote is included in Marguerite Boland’s introduction to Carter’s formal practices (2012, 80–85). Boulez ([1956] 1990) and Stockhausen (1963) were leaders in European developments in compositional form, speaking publicly about the topic, and analyzing and writing about form in Debussy and Webern.

2. One of the most discussed examples of distinctive musical layers in Carter’s music is his Second String Quartet, composed in 1959 (Bernard 1993, Koivisto 1996, Roeder 2012, 110–114).

3. All of these sources discuss Carter’s use of polyrhythm in “Anaphora” as well as analyzing other songs from the Mirror cycle.

4. Streams with contrasting musical behaviours also characterize other mid-period vocal works, including other songs from the Mirror cycle (Shreffler 1993); in Syringa (1978) Carter extends the concept of stratification by adding a second vocal layer in the form of the bass voice that comments in ancient Greek while the soprano sings the Ashbery text.

5. The seemingly contrary element of Moore’s poetry from this period would undoubtedly have appealed to Carter, whose “well developed appreciation of irony, wit, and contradiction” is discussed by Ravenscroft (2012, 272).

6. The online Merriam-Webster dictionary defines “bulwark" as “1 a. a solid wall-like structure raised for defense: rampart; b. breakwater, seawall; 2. a strong support or protection; 3. the side of a ship above the upper deck” ("http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/bulwark," accessed 3 March 2016)

7. The soprano’s highest pitch, Ab5, is the highest pitch of the opening measures, giving the passage its darker (lower) registral color.

8. Fixed pitch/register schemes are used in other Carter songs, for example “Anaphora” from A Mirror on Which to Dwell, and “End of a Chapter” from Of Challenge and Of Love.

9. This property is not unique; a further sixteen hexachords share the same subset property with the ATH.

10. When he set the poem to music, Carter also set the title as part of the first line of the poem, clarifying Moore’s opening single word “affirmed.” A similar practice can be observed in “O Breath” from A Mirror on Which to Dwell.

11. This instance of morphing differs from those discussed by Boland not only by chord type, but also texturally; rather than common pitches being presented linearly in different instruments (see Example 7 on p. 42), here they are reiterated through the violin’s repeated chords.

12. Identifying Carter’s “unswerving focus on the vocal line” as a characteristic of Carter’s songs since his return to vocal writing in 1975, John Link discusses how Carter’s “first-person lyric perspective” takes form in A Mirror on Which to Dwell, Syringa, and In Sleep, In Thunder (2012, 36–38).

13. This example corrects an error in the second violin and cello parts of the printed score, where rests on the downbeat of the second quarter note are notated as triplet eighths instead of triplet sixteenths.

14. The rhythmic coordination between the instruments as they articulate the sixteenth-note subdivisions of the first beat in m. 7 might at first suggest that the sustained chords of before have simply sped up; this impression is soon discharged once the rhythmic activity becomes more varied between the instruments later in the bar.

15. Boland draws on this concept in her definition of “linking gestures,” which “contain some pitch and interval material that has just been heard, as well as some material that is about to be heard in the next event or texture” (2006, 35).

16. Although the start of section B was generalized in Example 1 as starting in m. 31 with the first sustained chord, the participation of the m. 30 sixteenth-note chord in the pulse arguably makes it part of the return. There is, in fact, no single point of articulation between sections B and A1. This early pulse attack mirrors the late pulse attack that occurs in m. 7 of the transition from sections A to B.

17. Other pitch features such as spatially fixed pitches and the chromatic aggregate are not evident here.

18. Here the composer’s focus is more on his notational solution to acceleration and deceleration than their expressive effect. The same rhythmic devices are features in Carter’s Double Concerto, where the solo instruments and orchestra contribute individual attacks that combine to form a long-range accelerando, and, later, ritardando (Bernard 1990, 188–96).

19. Similar musical “jokes” abound in Carter’s works. For example, in “End of a Chapter” the expected final attack of the established pulse in the vocal part is omitted, replaced by silence; shortly afterwards the voice enters with the word “absence.”

20. An example of word painting can be seen in m. 24 where Carter reflects the almost palindromic play on words (“lead saluted, saluted by lead”) with a series of brief symmetrical pitch gestures, bracketed and marked “P” in Example 11a. See for example the strings, beats two to four, and the vocal setting of “saluted.” The palindromic gestures are more extended in m. 22, leading up to and accompanying the first statement of “lead” (not shown).

21. In a typically Carteresque off-kilter moment, there is a near miss on first beat of m. 30 where an accented instrumental attack enters prematurely, one sextuplet sixteenth earlier than the accelerando attack in tom-toms.

22. Carter’s treatment of signature sets in this way was established early in his compositional career. Explaining the role of the AIT in his First String Quartet (1951), for example, he states that one of the ways in which a “key chord” can “function… as a formative factor” (in addition to being used in significant points in the music), is by being presented with “the number of notes… increased and diminished in it...” (Carter [1960] 1997, 219). Jonathan W. Bernard discusses pentachordal “supersets” as a way of analyzing passages where the AIT is not explicitly present to show that it is nonetheless contributing to the sense of coherence and continuity in the music (Bernard 1993, 244–45). Starting at the end of m. 28, Carter excludes the first violins from participation; instead they double the harp with a high D♯7 harmonic.

Works Cited

Bernard, Jonathan W. 1990. “The Evolution of Elliott Carter’s Rhythmic Practice.” Perspectives of New Music 28 (1): 164–203.

________. 1993. “Problems of Pitch Structure in Elliott Carter’s First and Second String Quartets.” Journal of Music Theory 37 (2): 231–66.

________. 1995. “Carter and the Modern Meaning of Time.” Musical Quarterly 79 (4): 644–82.

Boland, Marguerite. 2006. “’Linking’ and ‘Morphing’: Harmonic Flow in Elliott Carter’s Con Leggerezza Pensosa.” Tempo 60 (237): 33–43.

________. 2012. “Ritornello Form in Carter’s Boston and ASKO Concertos.” In Elliott Carter Studies, eds. Marguerite Boland and John Link, 80–109. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Boulez, Pierre. (1956) 1990. “Form.” In Orientations, ed. Jean-Jacques Nattiez, trans. Martin Cooper, 90–96. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Capuzzo, Guy. 2000. ”Variety within Unity: Expressive Ends and their Technical Means in the Music of Elliott Carter, 1983–1994.” Ph.D. diss. Eastman School of Music, University of Rochester.

________. 2012. Elliott Carter’s What Next?: Communication, Cooperation and Separation. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Carter, Elliott. (1960) 1997. “Shop Talk by an American Composer (1960).” In Elliott Carter: Collected Essays and Lectures, ed. Jonathan W. Bernard, 214–24. New York: University of Rochester Press.

________. (1976) 1997. “Music and the Time Screen (1976).” In Elliott Carter: Collected Essays and Lectures, ed. Jonathan W. Bernard, 262–80. New York: University of Rochester Press.

________. 1977. “Double Concerto for Harpsichord and Piano with Two Chamber Orchestras; Duo for Violin and Piano [Program Notes].” In The Writings of Elliott Carter: an American Composer Looks at Modern Music, eds. Else Stone and Kurt Stone, 326–30. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Coulembier, Klaas. 2012. “Elliott Carter’s Structural Polyrhythms in the 1970s: ‘A Mirror on Which to Dwell’.” Tempo 66 (261): 12–25.

Edwards, Allen. 1971. Flawed Words and Stubborn Sounds: a Conversation with Elliott Carter. New York: Norton.

Hewett, Ivan. 2008. “Elliott Carter: Adventures of an American Legend.” The Daily Telegraph, December 3. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/3563923/Elliott-Carter-Adventures-of-an-American-legend.html.

Holley, Margaret. 2009. The Poetry of Marianne Moore: A Study in Voice and Value. London: Cambridge University Press.

Koivisto, Tiina. 1996. “Aspects of Motion in Elliott Carter’s Second String Quartet.” Intégral 10: 19–52.

Link, John. 1994. “Long-range Polyrhythms in Elliott Carter’s Recent Music.” Ph.D. diss. City University of New York.

________. 2012. “Elliott Carter’s Late Music.” In Elliott Carter Studies, 33–54.

Mead, Andrew. 2012. “Time Management: Rhythm as a Formal Determinant in Certain Works of Elliott Carter.” In Elliott Carter Studies, 138–67.

Poudrier, Ève. 2009. “Local Polymetric Strutures in Elliott Carter’s 90+ for Piano (1994).” In The Modernist Legacy: Essays on New Music, ed. Björn Heile, 205–33. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Ravenscroft, Brenda. 1999/2000. “The Moon and the Insomniac: Musical Personae in Elliott Carter’s ‘Insomnia.’” SAMUS 19/20: 57–70.

________. 2003. “Setting the Pace: the Role of Speeds in Elliott Carter’s A Mirror on Which to Dwell.” Music Analysis 22: 253–82.

________. 2012. “Layers of Meaning: Expression and Design in Carter’s Songs.” In Elliott Carter Studies, 271–91.

Roeder, John. 2012. “’The Matter of Human Cooperation’ in Carter’s Mature Style.” In Elliott Carter Studies, 110–37.

Rosen, Charles. 1984. “An Interview with Elliott Carter.” In The Musical Languages of Elliott Carter, 33–43. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress.

Sallmen, Mark. 2007. “Listening to the Music Itself: Breaking Through the Shell of Elliott Carter’s ‘In Genesis’.” Music Theory Online 13 (1).

Schiff, David. 1983. The Music of Elliott Carter. New York: Da Capo Press.

________. 1998. The Music of Elliott Carter. Revised second edn. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Shreffler, Anne C. 1993. “Give the Music Room’: Elliott Carter’s ‘View of the Capitol from the Library of Congress’ aus A Mirror on Which to Dwell.” In Quellenstudien II, ed. Felix Meyer, 255–83. Winterhur: Amadeus Verlag.

Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 1963. “Von Webern zu Debussy: Bemerkungen zur statistischen Form.” In Texte zur elektronischen und instrumentalen Musik, ed. Dieter Schnebel, 75–85. Cologne: DuMont.

Weston, Craig. 1992. “Inversion, Subversion, and Metaphor: Music and Text in Elliott Carter’s A Mirror on Which to Dwell.” DMA diss. University of Washington.

Zimmerman, Robert. 1998. “The Poetics of Polyrhythm in Elliott Carter’s Anaphora.” Sonus 19(1): 67–85.