Fuzzy Edges: Notes on Musical Interaction in the Music of Elliott Carter*

Andrew Mead

Abstract

Much of Elliott Carter’s music of the past half-century has depended on combinations of different musical characters, defined by expressive qualities, playing modes, pitch language, rhythm and tempo. These different characters are often situated in rhythmic grids, many of which are determined by large-scale long-range polyrhythms. Many of these features have been examined elsewhere, with particular concern to the mechanics of creating the sorts of pitch and rhythmic structures upon which Carter’s musical characters depend. The present essay is less concerned with the mechanics of their creation than with the different kinds of compositional realizations Carter brings to the ways musics of varied characters interact, both with each other and with his underlying metrical grids. Examples are drawn from four compositions to illustrate the flexibility and fluidity of Carter’s invention in the interpretation of his underlying musical designs.

* This article was first published in French as « Abords indistincts: quelques considérations sur l'interaction musicale chez Elliott Carter » in Hommage à Elliott Carter, trans. and ed. Max Noubel (Sampzon: Éditions Delatour France, 2013), pp. 117-146. It is published here for the first time in the original American English. [eds.]

[ 1 ] Much of Elliott Carter’s music of the past half-century has depended on combinations of different musical characters, defined by expressive qualities, playing modes, pitch language, rhythm and tempo. These different characters are often situated in metrical grids, many of which are determined by large-scale long-range polyrhythms. Many of these features have been examined elsewhere, with particular attention to the mechanics of creating the sorts of pitch and rhythmic structures upon which Carter’s musical characters depend. My interests in the present essay are less concerned with the mechanics of these structures than with the different kinds of compositional realizations Carter brings to the ways musics of varied characters interact, both with each other and with his underlying metrical grids. In the following I will examine passages from four compositions to illustrate the flexibility and fluidity of Carter’s invention in the interpretation of his underlying musical designs.

[ 2 ] As has been discussed elsewhere, Carter’s String Quartet no. 3 (1971) is made up of a mosaic of ten musical characters or movements divided four and six between two duos, the first consisting of the first violin and cello, and the second of the remaining two players.(1)See, for example, Schiff 1998, p. 85, Mead 1984, pp. 31-60, and Noubel 2000, pp. 165-71. Carter’s pattern offers all of the possible pairings between the characters of the two duos, plus solo presentations of all ten characters. Attention has been drawn to the ways that the characters interact between the two duos, but it is also worth taking a closer look at what happens as one character turns into another within a duo.

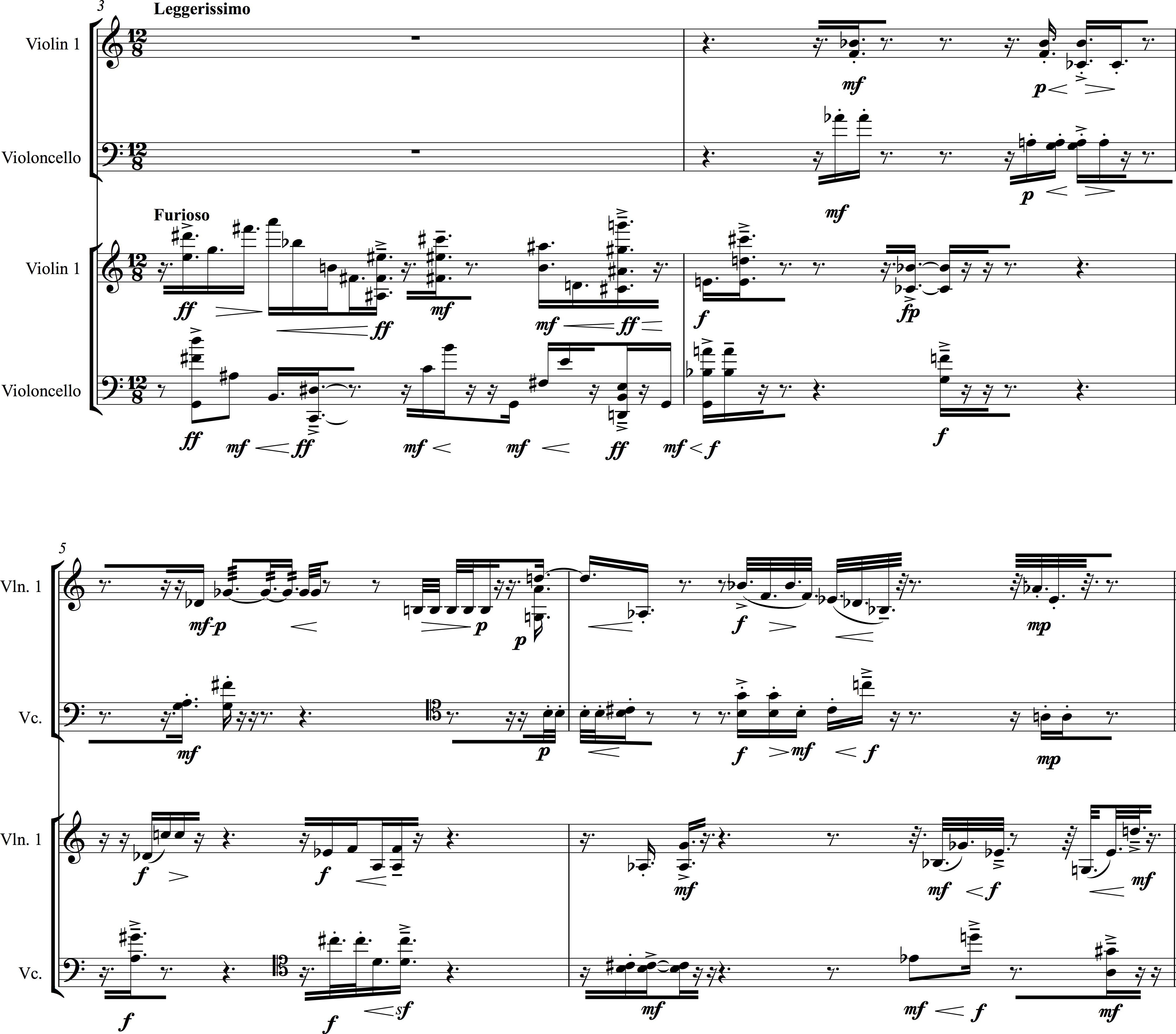

[ 3 ] Many of the changes of character within a duo happen abruptly; this is obviously true when one duo has been silent while the other duo presents a single character. Some are less abrupt, as when one instrument undertakes a new character a few beats earlier than the other. But a much more interesting situation arises in the shift from Duo I’s initial character (Furioso) to its next presentation (Leggerissimo). Here, the shift is gradual, with the latter character emerging in the texture while the former recedes. Example 1 illustrates bars 3 – 6 of Duo I’s music, renotated to separate the two characters onto different staves. It is worth noting that while Carter has assigned a different representative interval to each character (here, Major 7th with the Furioso music, and Perfect 4th with the Leggerissimo), the larger collections he is employing allow him to create a pitch continuity through the alternations of character.(2)See Mead 1984 for a discussion of pitch in this work.

Example 1

Elliott Carter, String Quartet No. 3, Duo I, mm. 3-6

© Copyright 1973 by Associated Music Publishers, Inc.

[ 4 ] Even these alternations may vary. For example, the first incursion of the leggerissimo music in bar 4 is itself interrupted by an abrupt furioso moment, while other passages, such as the end of bar 6, seem to move, through a crescendo and change of articulation, from one character to another within a single event. This sort of shifting within a larger more continuous continuity, here determined by both pitch and instrument, invites an interpretation of these characters as different facets of some larger, more complex entity capable of exhibiting different behaviors. Since Carter has been known to liken aspects of his music to different human activity, it would seem plausible to think of each duo as a kind of personality, each of which has a repertoire of behaviors that variously emerge in the piece.

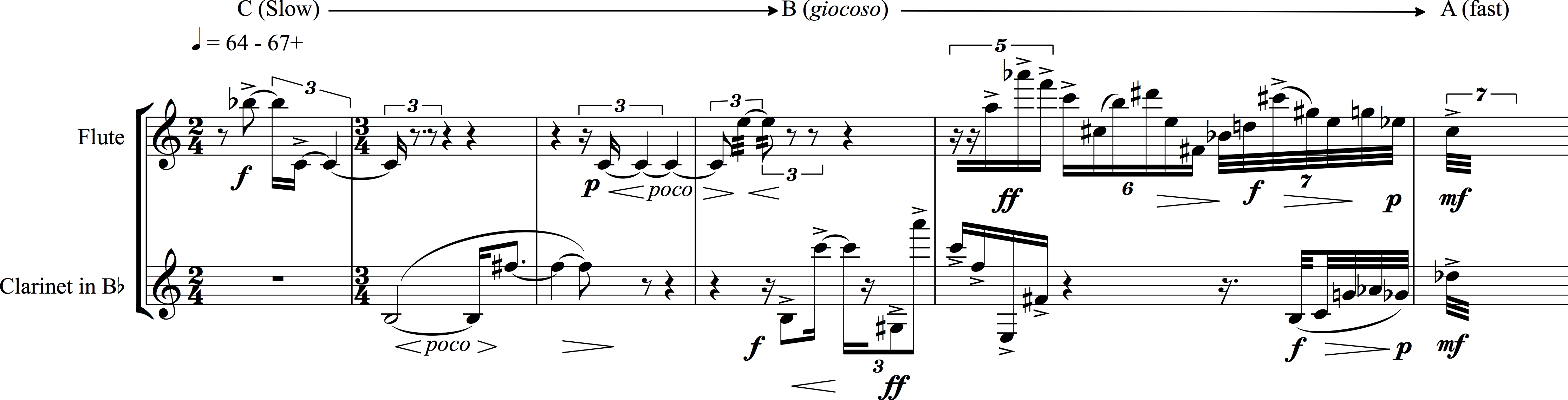

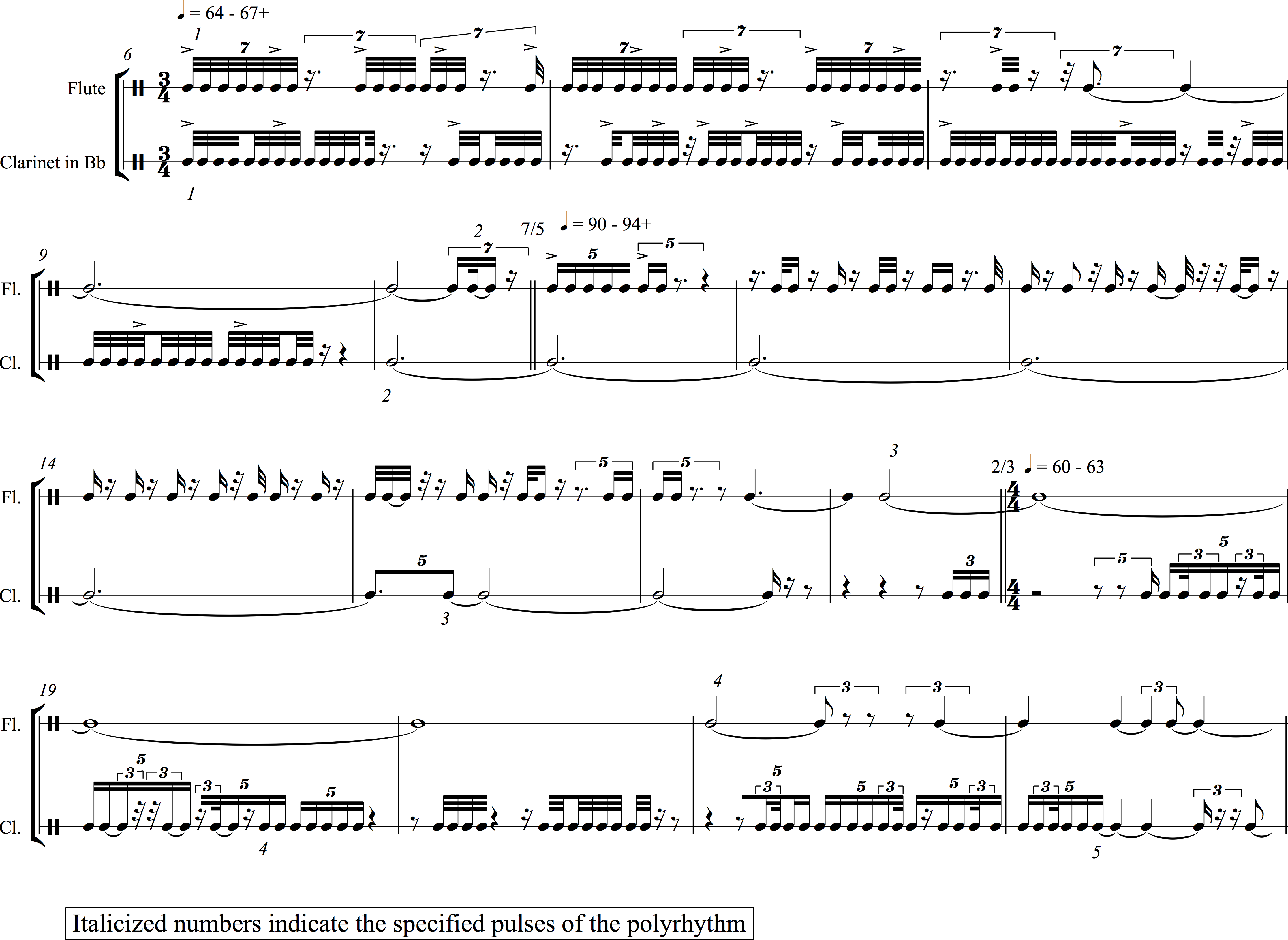

[ 5 ] A similar fluidity of character can be found in the duo for flute and clarinet, Esprit rude/esprit doux (1984), which, according to David Schiff, is based on three musical characters.(3)Schiff 1998; see the discussion on pp. 139-141. These characters may be generally described as fast, giocoso, and slow, and I will refer to them respectively as A, B and C, but each character itself has various facets, and can project a variety of affect. These characters are deployed within one of the large-scale polyrhythms that Carter used from 1980 to the mid ‘90’s. I am interested in considering both how these characters interact with each other in the composition, but also how those interactions connect with the underlying polyrhythm.(4)Roeder 2012 makes a number of related observations.

Example 2

Elliott Carter, Esprit rude/Esprit doux, mm. 1-6

© Copyright 1985 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

[ 6 ] The very opening of the duo can help prepare us for the mutability of its characters. Example 2 contains the first five bars of the work, in which we encounter a progression from slow to fast, through the kind of wide disjoint leaps that will emerge as a feature of B, the giocoso music. This coming together unleashes the beginning of the large polyrhythm at the downbeat of bar 6. What follows is a rippling of fast, quiet music, out of which, in bar 8, the flute sustains a single pitch while the clarinet continues its rapid activity. This is illustrated in Example 3.

Example 3

Elliott Carter, Esprit rude/Esprit doux, mm. 6-9

© Copyright 1985 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

[ 7 ] A reasonable, if premature, assumption at this point might be that we will hear an orderly series of combinations of the three musical characters in pairs between the two instruments, but that swiftly proves not to be the case. Within a few bars the instruments exchange the act of sustaining a tone against activity in the other instrument, and then trade back again. Moreover, the music in the other instrument engages features of both what I have labeled A and B. Example 4 offers a few bars in which the clarinet moves between these two characters while the flute sustains a tone. Similar behavior continues throughout the piece, and while we do find passages in which both instruments are playing the same characters, or are each limited to a single character, we also come across passages in which each instrument is combining more than one character. Example 5 is a rough chart of these interactions.

Example 4

Elliott Carter, Esprit rude/Esprit doux, mm. 18-21

© Copyright 1985 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

Example 5

Elliott Carter, Esprit rude/Esprit doux - Interactions of the three musical characters

[ 8 ] As may be seen, the music exhibits a number of ways that the three characters may interact. There are examples of passages in which both instruments are participating in a given character, including two versions of C (both piano and forte), and two instances of a kind of music that would seem to be outside the basic repertoire of A, B and C.(5)Schiff 1998, pp. 139-41, both identifies these three musical characters and further connects some of these differences with the title of the work, which refers to contrasting breathing patterns in classical Greek. This latter music, formed of tremolos in each instrument, would seem to combine the slower pitch change of C with the density of attack associated with A. Several passages variously combine A and B in one or the other instrument, while the remaining player sustains a tone in the manner of C. In the passage starting near bar 65, we find the soft rapid music associated with A interspersed at longer temporal intervals with short, loud stressed notes. I read this as a combination of A and C within each instrument, with C represented by the higher dynamic and the relatively long time spans so articulated. As the preceding suggests, Carter’s invention yields a wide variety of ways of combining the duo’s musical characters, both between and within the work’s instruments.

[ 9 ] My second consideration involves the large-scale polyrhythm of 25:21 that spans the work, initiated on the downbeat of bar 6, and closing with the downbeat of bar 88, the final bar of the piece. Example 6 is the polyrhythm as it appears in the music’s varying metrical grid. Once again, I am not presently interested in constraints involved in creating such a polyrhythm, or realizing it within varying tempos and meters. What is of primary interest at the moment is how this structure interacts with the changing characters of the music.(6)See Mead 2012 for a detailed discussion of this polyrhythm, and a more general consideration of the issues surrounding constructing long-range polyrhythms using traditional notational constraints. See also Mead 2007.

Example 6

Elliott Carter, Esprit rude/Esprit doux - Realization of the polyrhythm

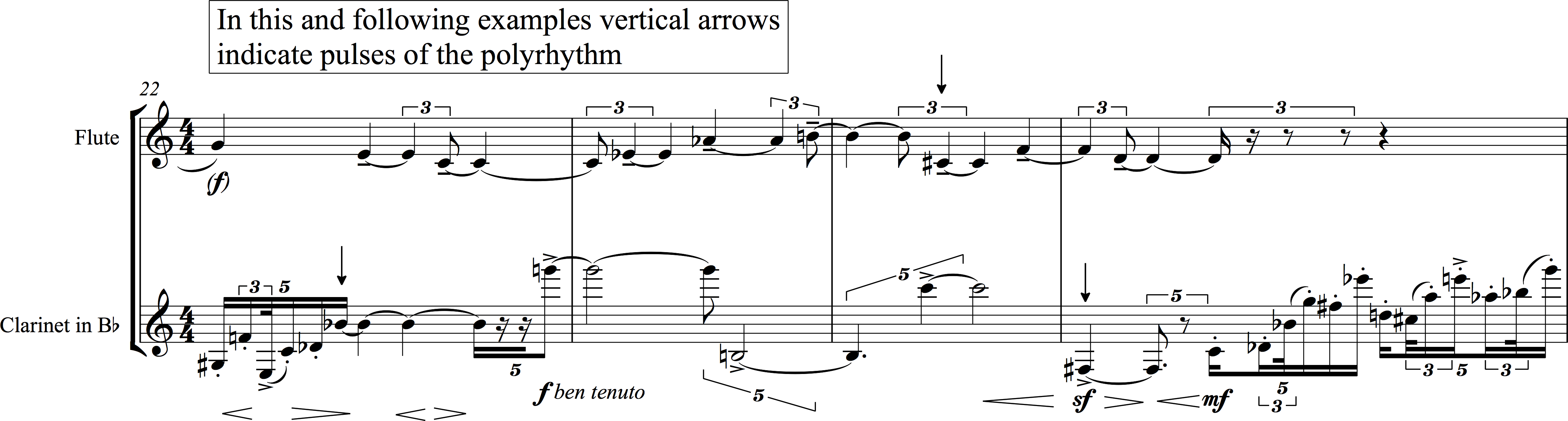

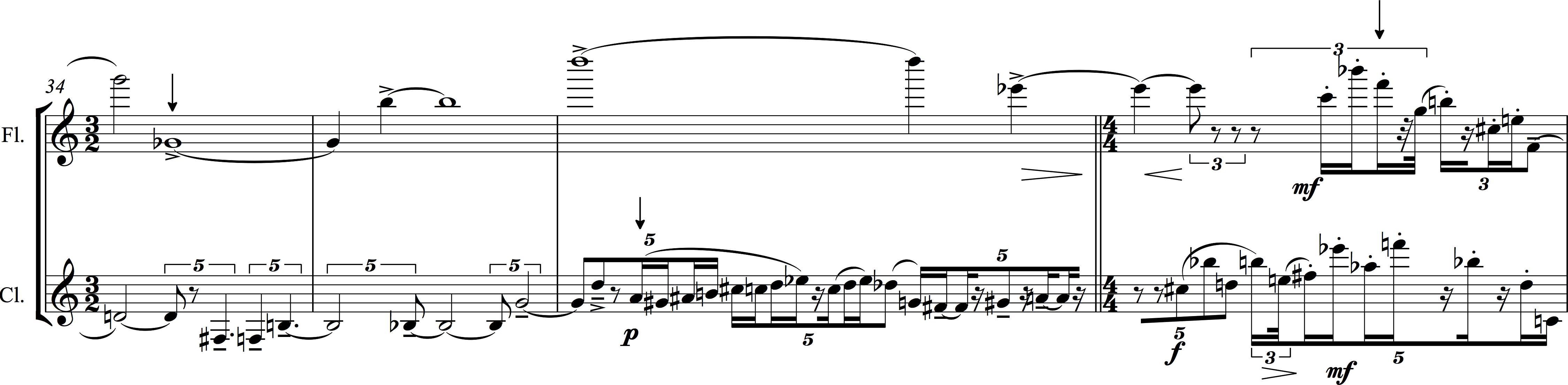

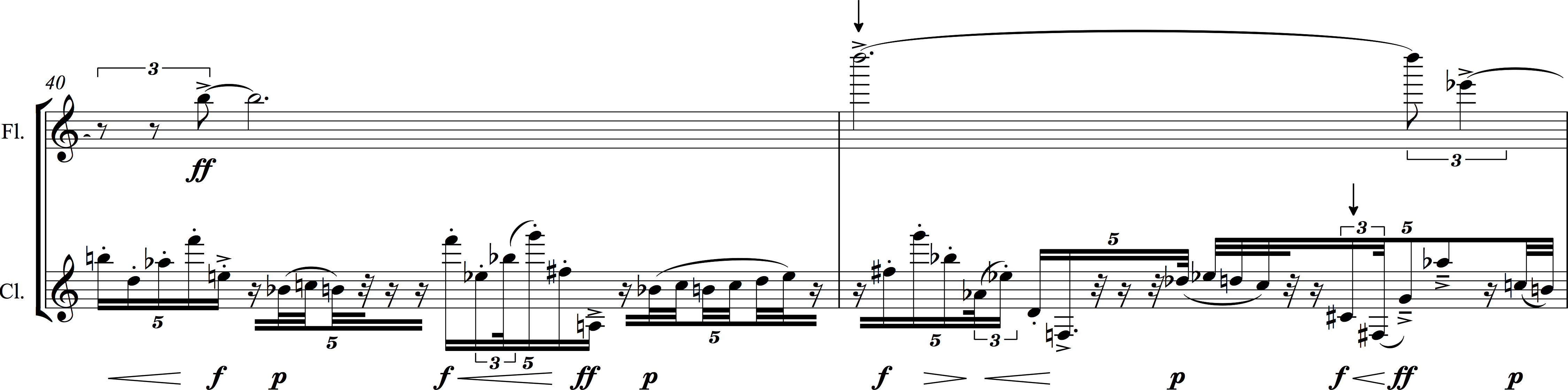

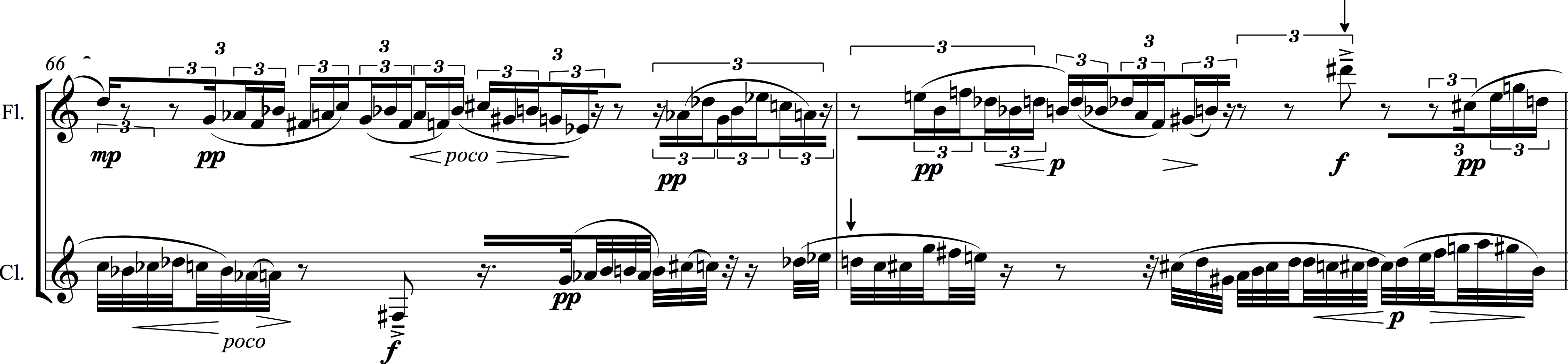

[ 10 ] Close inspection reveals that the elements of the polyrhythm are engaged in a variety of ways with the musical characters, sometimes marking the beginning of a character, sometimes articulated by the last event of a character, or sometimes falling within a character. Example 7 offers a number of illustrations: as may be seen in the first line of the example, the vertical arrow marking the polyrhythmic pulse in the flute part occurs in the midst of the flute’s line, while those in the clarinet both mark the arrival points of the music preceding them. In the second line, the first arrow in the flute part is in the middle of a slower line, while the second is preceded by a quick up-beat; the arrow in the clarinet part marks the beginning of a rapid little flourish. Similar observations may be made about the rest of the example. Perhaps the most interesting aspect is found in the last line of the example, where a singled-out note in the flute is part of its larger polyrhythm, while an analogous note in the previous bar, played by the clarinet, is not.

Example 7

Elliott Carter, Esprit rude/Esprit doux

© Copyright 1985 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

a) mm. 22-25

b) mm. 34-37

c) mm. 40-41

d) mm. 66-67

[ 11 ] But while the elements of the polyrhythm are not always simple junctures amongst characters, their presence, and the contingencies of their metrical realization can indeed help shape the articulation of the musical surface in significant ways. Consider Example 8. This example is a rhythmic reduction of bars 6 through 22, and encompasses the initiation and first few elements of each limb of the polyrhythm. As may be seen, the flute’s first character shift, from A to C, occurs during its limb’s first time span.(7)"Limb" refers to a single strand of a polyrhythm, so that a polyrhythm of 25:21 would have two limbs, one of 25 elements (timespans) and one of 21 elements. "Timespan" here, as may be inferred, refers to a single element of the limb of a polyrhythm. The shift occurs, however, exactly half way through the span, and we are offered in the flute part a way of sensing the simple subdivisions of larger spans. If we track the accentuation patterns in the flute’s rapid music before this, we establish an even pulse stream made of groups of five of the septuplet subdivision. Each element of this even pulse stream occurs in the music, although not all are filled in. Nevertheless, we have a reasonably perceivable pulse stream in which we can then embed and measure the following long note. The rapid music unfolds over 10 of these pulses in the flute, and the subsequent long note is of the same length. When the flute next articulates a time span, it does so in a way that recaptures this same pulse stream, which is now the notated tactus. This tactus is articulated to lesser and greater degrees over the next few bars, but by bar 14 it is very much at the surface, and so can help us gain the measure of the music up to the next sustained note in the flute, which initiates the third span of its limb of the polyrhythm.

Example 8

Elliott Carter, Esprit rude/Esprit doux, mm. 6-22 - Rhythm

[ 12 ] Meanwhile, the clarinet is providing access to its underlying metrical world as conditioned by its limb of the polyrhythm. During the opening rapid music, it too is providing groupings of its own thirty-second note subdivisions by accents. These are in threes, or multiples of threes, and while not as regular as those in the flute, these produce a pulse stream that evenly divides the four bars of 3/4 that precede the clarinet’s own first change of texture, a sustained tone. This also marks the initiation of the second span of the clarinet’s limb of the polyrhythm. As may be seen, the clarinet’s subsequent spans in the example are each marked in various ways by shifts of musical texture, be it the initiation of another long note, or the change from the little local polyrhythms of the giocoso music to a more regular motion, or the resumption of slower sustained music.

[ 13 ] Needless to say we have no immediate way of knowing that a given moment or change of texture is marking the initiation of a new span in one or the other limbs of the polyrhythm, but what does emerge from this scrutiny is that beneath the delightfully unpredictable spontaneity of the musical surface is a regularity within each instrument that we can begin to discern. The complexity of the music arises from the interaction and intersections of these larger simpler patterns, as well as the fertility of imagination that Carter brings to bear on their realizations.

[ 14 ] Our next example is drawn from another brief composition from ten years later, Esprit rude/Esprit doux II for flute, clarinet and marimba. This work is a kind of sequel or continuation of the first composition, and may be combined with it in performance. Unlike the earlier duo, it is harder here to define fixed musical characters, and such differences are more permeable. One of the special features of the composition is the way the different kinds of music may mutate into each other. Once again, a large-scale polyrhythm is present, but in this case there are three limbs, and the composition contains only a fragment of the whole.(8)See Schiff 1998, pages 148 and 149 for his take on this music. I find myself in disagreement with his analysis of the polyrhythm. For a lengthier discussion of the technicalities of this and other polyrhythms, see Mead 2012.

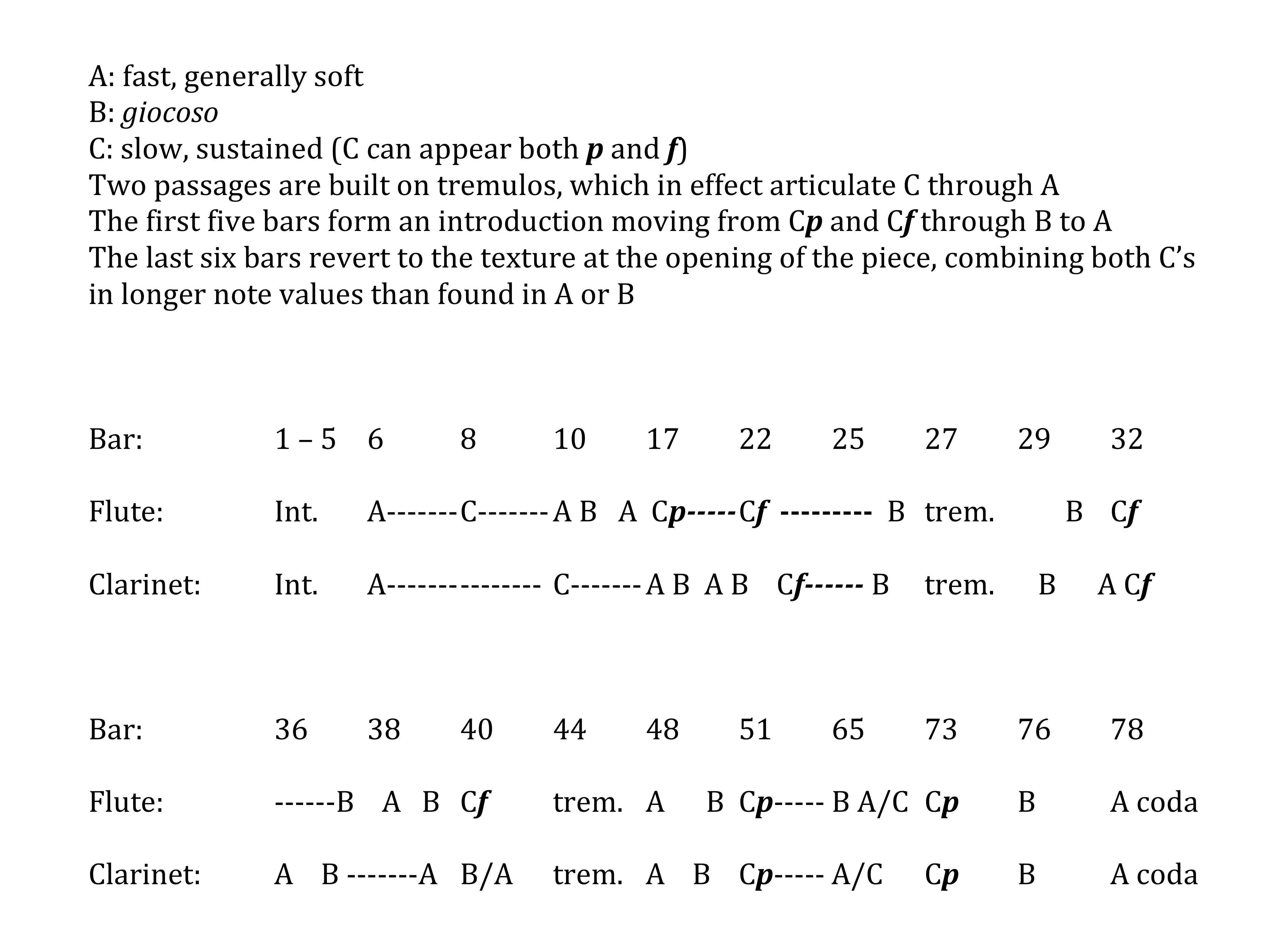

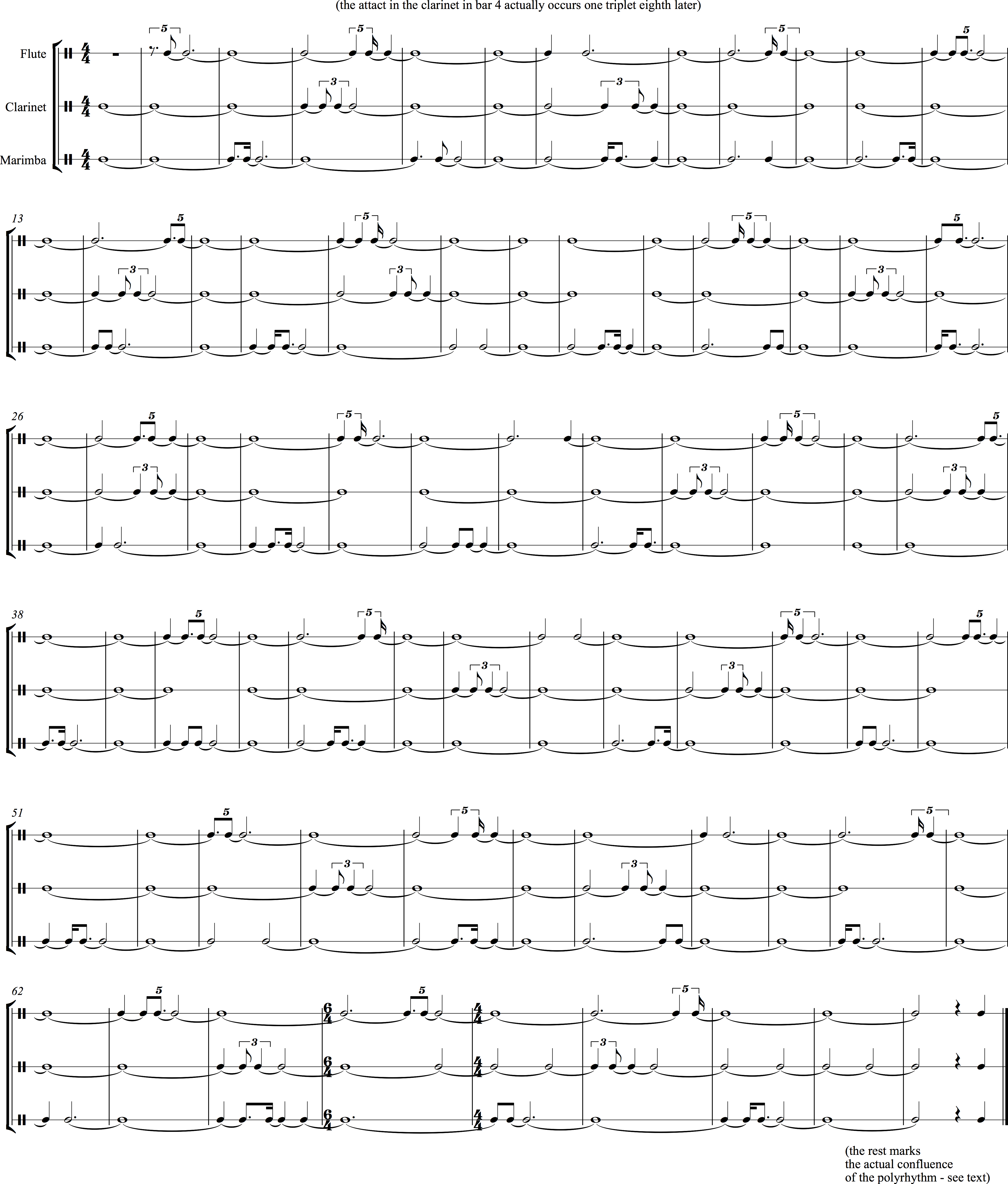

[ 15 ] Example 9 is a realization of the polyrhythm as it appears in the work’s metrical grid. As may be seen, the clarinet and marimba’s parts contain a complete polyrhythm between them of 21:32, but the flute’s time spans begin slightly after this moment. A complete cycling of the flute’s time spans against the combination of the other two instruments would unfold over a much larger duration than what is present. Interestingly, the final simultaneity of the piece, marking the coincidence of the three instruments, is delayed by one beat of the notated meter, and the actual moment of coincidence is marked by silence.(9)Schiff 1998, p. 149, notes this detail in his discussion.

Example 9

Elliott Carter, Esprit rude/Esprit doux II - Realization of the polyrhythm

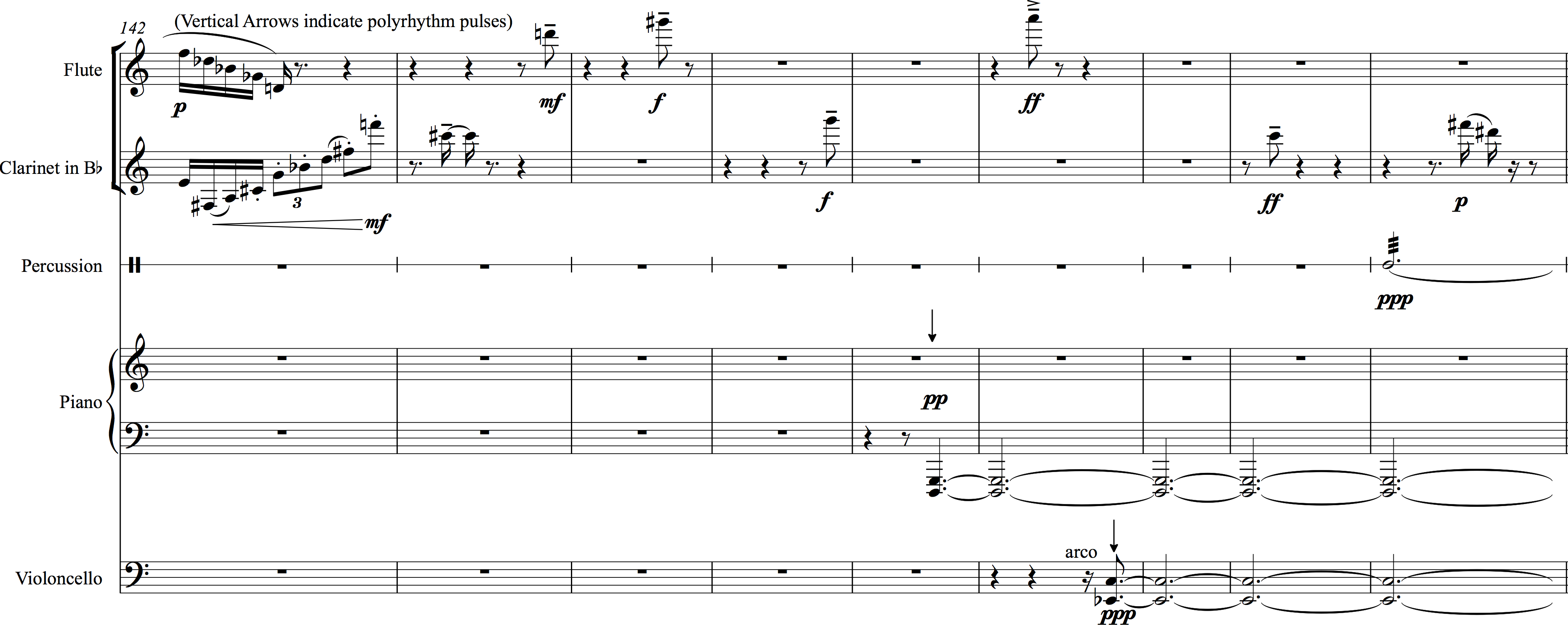

[ 16 ] Once again we will be concerned with the interaction of the musical surface with the underlying polyrhythm, but we shall take a somewhat different approach to considering the question. By concentrating on a single strand of the composition, the flute’s part, we will be able to observe both how the polyrhythm establishes certain sorts of individual metrical constraints in each instrument, and how a given instrument’s music can offer multiple interpretations of different sorts of musical action.

[ 17 ] Example 10 is a reduction of the flute’s rhythms laid out against the flute’s limb of the polyrhythm. As may be seen, the polyrhythm unfolds at the rate of one attack every 51/5 beats of the notated meter, or to put it another way, every 51st quintuplet eighth note. At the outset, we can observe that the flute part further divides its limb into groups of three attacks per limb element, establishing a slow steady pulse stream of attacks at every 17/5 beats of the notated meter. Looking through the example reveals how often this triple subdivision of the limb’s elements is articulated, either as part of a long slow sustained unfolding, or as the initiation of different kinds of textural change. One interesting point is how in some passages the flute’s shorter durations progressively lengthen to restore this underlying pulse. See the passage following bar 35, for an instance of this behavior.

Example 10

Elliott Carter, Esprit rude/Esprit doux II

The flute's limb of the polyrhythm together with a rhythmic skeleton of its part

[ 18 ] Example 11 offers a portion of the actual flute part. With the pitches, articulations and dynamics in place, it is possible to see that the sorts of distinctions amongst musical characters we observed in the earlier duet are here blurred. For example, the fastest rates of attack are actually tremolos whose rate of pitch change are as slow or slower than the long notes at the outset. One might add to that observation the use of flutter tongue, which can give the sense of great speed, but also occurs on sustained pitches. Similarly, while the music through the end of bar 9 and through 10 speeds up the rate of change, associated here with staccato notes, the continuation of staccato at the end of 10 and 11 reestablishes the slow pulse rate of the long notes at the outset. Additional complications along these lines are generated by the interaction of staccato, flutter tongue and tremolo in the music in bar 20 and following. The sense to me of these passages is not so much a series of distinctions between different kinds of music, but a flow amongst them. Different criteria entailing sustain, attack and even dynamics can invite the listener to associate a given event with a variety of different passages, allowing one to think in terms of musical mutability as opposed to identity.

Example 11

Elliott Carter, Esprit rude/Esprit doux II, mm. 1-35

flute part together with its limb of the polyrhythm

[ 19 ] This sense is compounded when we encounter the combination of the whole ensemble. Example 12 offers some bars from the middle of the work. Following each part, one encounters quite rapid shifts amongst short staccato notes, notes that are sustained but activated by tremolo or flutter tongue, and slurred, looping melodies. But it is also possible to parse the passage by these distinctions rather than by instrument, as may be found in the lower set of staves in the example. Doing so reveals a longer continuity in the passage, cutting across the instrumental diversity. Nevertheless, a blurring amongst these layers of texture, as well as their associations with other places in the composition, occurs when one considers how the lyrical lines in the flute can be heard as a filling in of the kinds of attack patterns found in bars 9 and 10 (see Example 11), or how the sustained flutter tongue and tremolo in the instruments combines both a slow attack rhythm with the impression of rapidity. The work as a whole seems constantly in the process of change, evolving from one state to another. When one hears the two Esprit rude/Esprit doux works back to back, it is fascinating to notice the difference between them solely based on how they each treat a multiplicity of musical identities.

Example 12

Elliott Carter, Esprit rude/Esprit doux II, mm. 33-42

© Copyright 1994 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

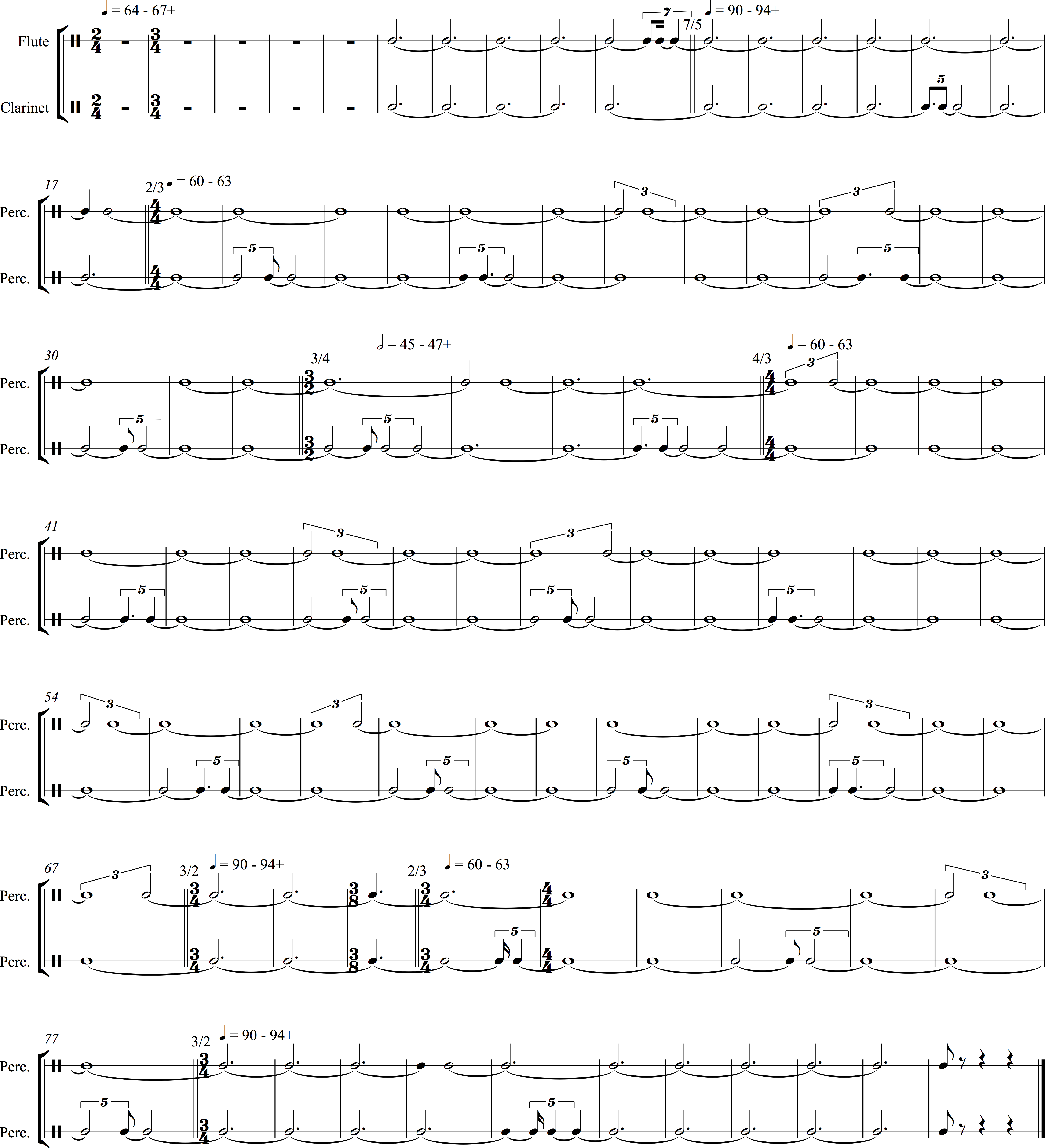

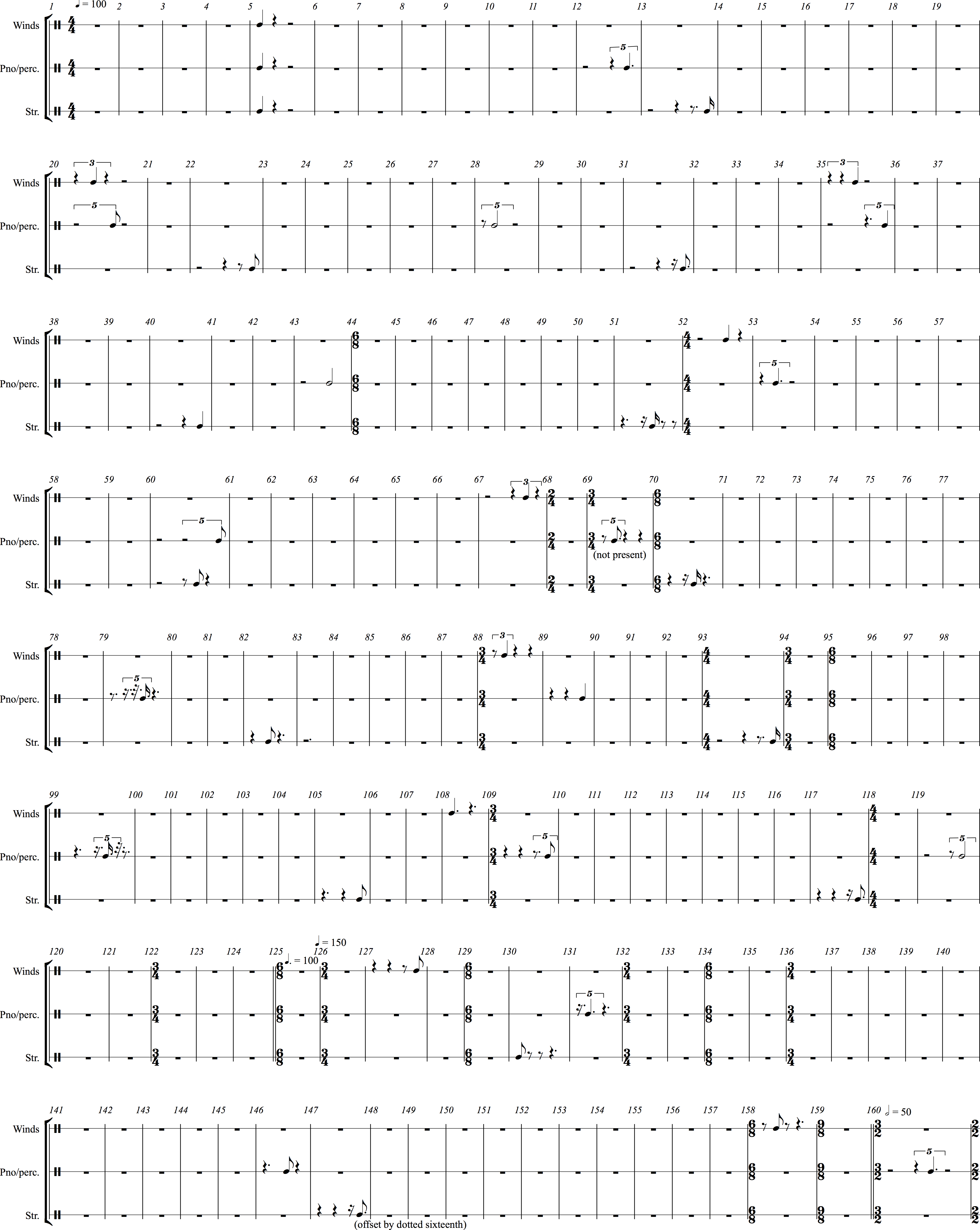

[ 20 ] Our final example is drawn from a larger-scale composition, the Triple Duo of 1983. This work divides a mixed sextet into a pair of winds, a pair of strings, and piano with percussion, both pitched and unpitched. Each duo unfolds its own limb of a three-part polyrhythm, and according to Schiff each duo has its own take on three basic musical characters, along the lines of the first Esprit rude/Esprit doux.(10)Schiff 1998; see pp. 120-124. The work contains a wide variety of musical situations, and it is beyond the scope of these notes to offer a detailed analysis of how these characters are articulated and combined. But it is still possible to consider how big changes in the composite musical surface interact with the articulations of the polyrhythm.

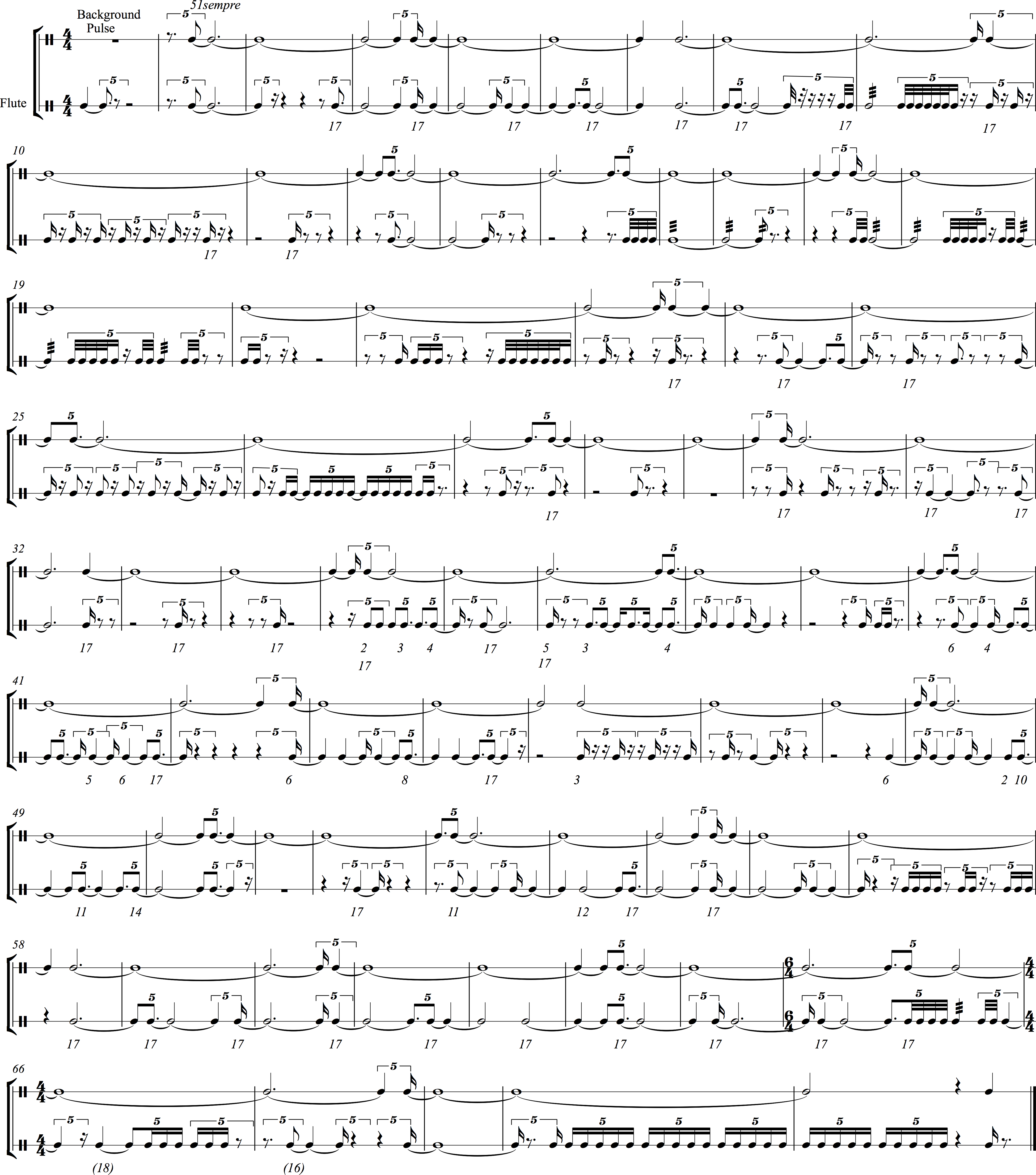

[ 21 ] Example 13 is a broad-brushed texture map of roughly the first half of the composition. It is a view of the work from afar, so to speak, in that it is made to indicate the more general changes of interaction amongst the duos rather than account for the nuances one encounters bar to bar. It indicates such distinctions as whether the music of a duo is generally sustained or active, continuous or intermittent, and in some cases, the appearance of a new instrument, or the return to one that has been absent. Passages in which a duo drops out for a significant span are also indicated. I have listed sections by bar number, but have also listed their duration based on a basic unit, the half-note of the initial tempo, in order to allow comparison of sections by length. This has been done to compensate for the changes of tempo and meter found throughout the work. As may be seen, even with so coarse a sieve we may sift out a considerable variety of musical interactions.

Example 13

Elliott Carter, Triple Duo, mm. 1-290 - texture plan

[ 22 ] Before considering how this map interacts with the underlying polyrhythm, it is worth taking a closer look to see how some of the distinctions indicated in Example 13 are blurred once one moves closer to the musical surface. Example 14 is drawn from the juncture between the second and third larger sections marked on the map. In the large, this is read as a shift from sustained music in the winds, with intermittent events in the string and piano/percussion duos to a more active solo in the piano and percussion, with sustained notes in the strings. The winds fall silent at this point. When we look closer, we find that while the winds are sustained for the body of the first passage, their departure from texture is marked by a brief flurry of activity, in response to a little eruption in the piano. This is a kind of precursor of the piano’s following solo, and embroiders and thickens the kind of single note thumps that the piano has been making for the past few bars. It is followed by another thump, which is also thickened into a trichord, preceding the low-register flourish that introduces the piano’s following more elaborate solo. The cello also blurs the change between sections by extending its single notes into a brief melody. Thus, while in the large there is a change at this point, the details of the change are not hard-edged.

Example 14

Elliott Carter, Triple Duo, mm. 30-37

© Copyright 1994 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

[ 23 ] The following three examples hint at the broad variety of ways Carter combines his various musical characters in these larger textural differences in the music. Example 15 is drawn from one of the solo presentations by the pair of stringed instruments. As may be seen, the passage is made of a mix of vigorous music, lighter more playful figures, and sustained notes. The rest of this solo passage is a similar intermixture of characters. And we can see here another instance of blurring. While the passage begins with the entrance of the strings’ vigorous music, it is briefly interrupted by a final hushed dyad in the clarinet, a kind of final tag from the wind duo’s music of the previous section.

Example 15

Elliott Carter, Triple Duo, mm. 70-74

© Copyright 1994 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

[ 24 ] Example 16 is an excerpt from a passage in which a representative of each of the duos contributes to a single musical character, one in which light flourishes act as upbeats to accented notes. I’ll have more to say about this later, but at the moment I offer it in contrast to Example 15. Example 17 offers still another contrast, excerpting a passage in which each duo is pursuing its own character, but each utterance is staggered so that the musical continuity shifts rapidly from duo to duo. All three of these examples are anecdotal, and are offered not as a comprehensive take on the modes of character mixture in the piece, but as a sampling of the rich variety that Carter brings to assembling his composition.

Example 16

Elliott Carter, Triple Duo, mm. 99-102

© Copyright 1994 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

Example 17

Elliott Carter, Triple Duo, mm. 238-42

© Copyright 1994 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

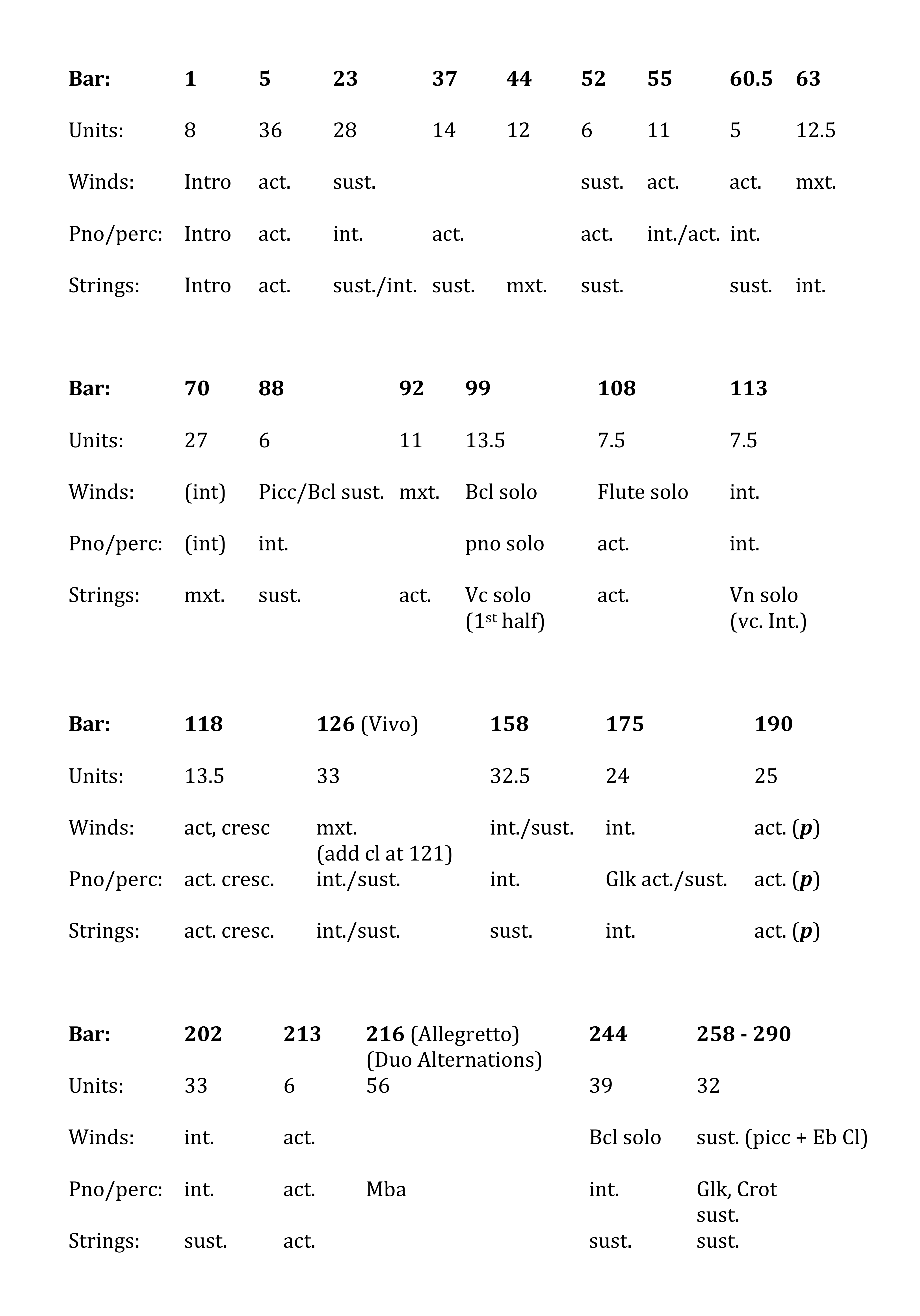

[ 25 ] We are now in a position to consider some more specific aspects of Carter’s use of polyrhythm in the Triple Duo, in particular his use of a large-scale three-part polyrhythm spanning the entire work. Example 18 is a representation of the three-part polyrhythm as it occurs during the music found in our texture map. This represents a little more than half the composition. The polyrhythm may be abstractly described as unfolding 33:65:56 in the winds, percussion/piano and strings, respectively. One may see that the durations of the individual spans of each duo may be expressed as 91/3 of a half-note for the winds; 77/5 of a half-note for the percussion/piano duo, and 143/8 of a half-note for the strings. The half-note in question is the notated half-note at the outset.

Example 18

Elliott Carter, Triple Duo - Representation of the polyrhythm (part 1)

(part 2)

[ 26 ] It is worth considering a couple of points initially. First, as David Schiff obliquely notes, the full extent of the polyrhythm is not expressed in the piece. That is to say, the gesture near the close of the work in which the ensemble unites on a single chord does not match the theoretical close of the polyrhythm, as the matching gesture in bar 5 marks its initiation. This does nothing to my hearing and appreciation for this work, as the polyrhythm itself is at such a great distance from the heard surface as not to be particularly salient in and of itself. In this piece, unlike the two preceding works, the attack points of the limbs of the polyrhythm are greatly spread out, so that they lie beyond the threshold of accurate durational perception. The most rapid limb, that in the percussion/piano duo, offers attacks at roughly twenty-second intervals, while the slowest, that of the winds, is around half that rate. This contrasts with the already slowly paced rate of unfolding of the works we have considered, or even of the 216:175 polyrhythm found in Night Fantasies, the work which initiated this practice. One may understand this difference by remembering that the sextet and the solo piano work are of comparable length.

[ 27 ] This leads us to ask what purpose the polyrhythm is serving in the composition. We can begin to understand this when we realize that by electing to use a polyrhythm in traditional notation, Carter is severely restricting the range of tempos and metrical grids within which it may be realized. I have discussed this elsewhere, so shall not detail it here.(11)See Mead 2007. But Carter is also using his assignment of the polyrhythm’s limbs to each duo to restrict the note-values each duo may use. Thus, the winds are usually playing some version of triplets, while the percussion/piano duo works with quintuplets, and the strings with duple configurations.

[ 28 ] Further, the background polyrhythm is only the largest scale use of the idea of music unfolding at different rates of equally spaced durations here. Another look at Example 14 can reveal that the flute and clarinet are unfolding layers in a ratio of 13:14 triplet quarter notes, and a more complex situation obtains between the bass clarinet, piano and cello in Example 16. In this passage, the accented finish to each instrument’s flourish creates an equally spaced pulse stream; 13/9 of the tactus (a dotted half-note), 14/10 and 11/8, respectively. Once again, the constraints Carter imposes on his rhythmic realizations sets limits on the nature of the sorts of ratios he may use both within and between duos.

[ 29 ] But despite, or perhaps because of, the background nature of the large-scale polyrhythm in the piece, it is interesting to pull back from the surface and see how it intersects with the texture map offered above. As has been the case for so many of our observations, Carter offers us a remarkable variety of ways that this occurs. Once again, a comprehensive list is beyond the scope of this essay, but we may begin to gain a sense of this variety in the following examples.

[ 30 ] Example 19 offers passages marking two major textural shifts. In the first, an initial passage combining active music in all three duos abruptly breaks off, leaving the winds playing long slow notes, while the strings play slightly faster dyads, leading in their case ultimately to a more intermittent presence. The piano in the music that follows only offers a couple of low thumps. A later portion of this passage was illustrated in Example 14. The two passages, the active one that opens the main body of the work, and the sustained music that starts here, are also contrasted dynamically. The shift is articulated by the strings’ quiet dyads, which are initiated on one of that duo’s polyrhythm attack points.

Example 19

Elliott Carter, Triple Duo

© Copyright 1994 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

a) mm. 22-24

b) mm. 51-53

[ 31 ] Example 19b is found at a juncture in which both the winds and percussion/piano duo reenter after a solo passage for the strings. As may be seen, this passage is a confluence of underlying attack points in all three duos at relatively close distances, and it is interesting to note how each is marked. For the strings, the attack point marks a shift in texture to sustained dyads. In the winds, the attack point is not found at the entrance, but is agogically, registrally and dynamically accented, allowing us to hear the preceding notes as a kind of upbeat. Similarly the piano offers a kind of upbeat to its attack point, which is also marked dynamically, as well as with a thickening of the texture and the percussionist’s strike upon a suspended cymbal.

[ 32 ] In keeping with our remarks about fuzzy edges, it is interesting to note how the shift from one general textural section to another in both of these examples is blurred in one way or another. In the latter of these passages, that blurring takes advantage both of the non-alignment of the underlying attack points from the polyrhythm, and the ways they are realized in the musical surface. In the former, it may be heard in the way the following low thumps in the piano seem to persist like flakes or echoes of its former music.

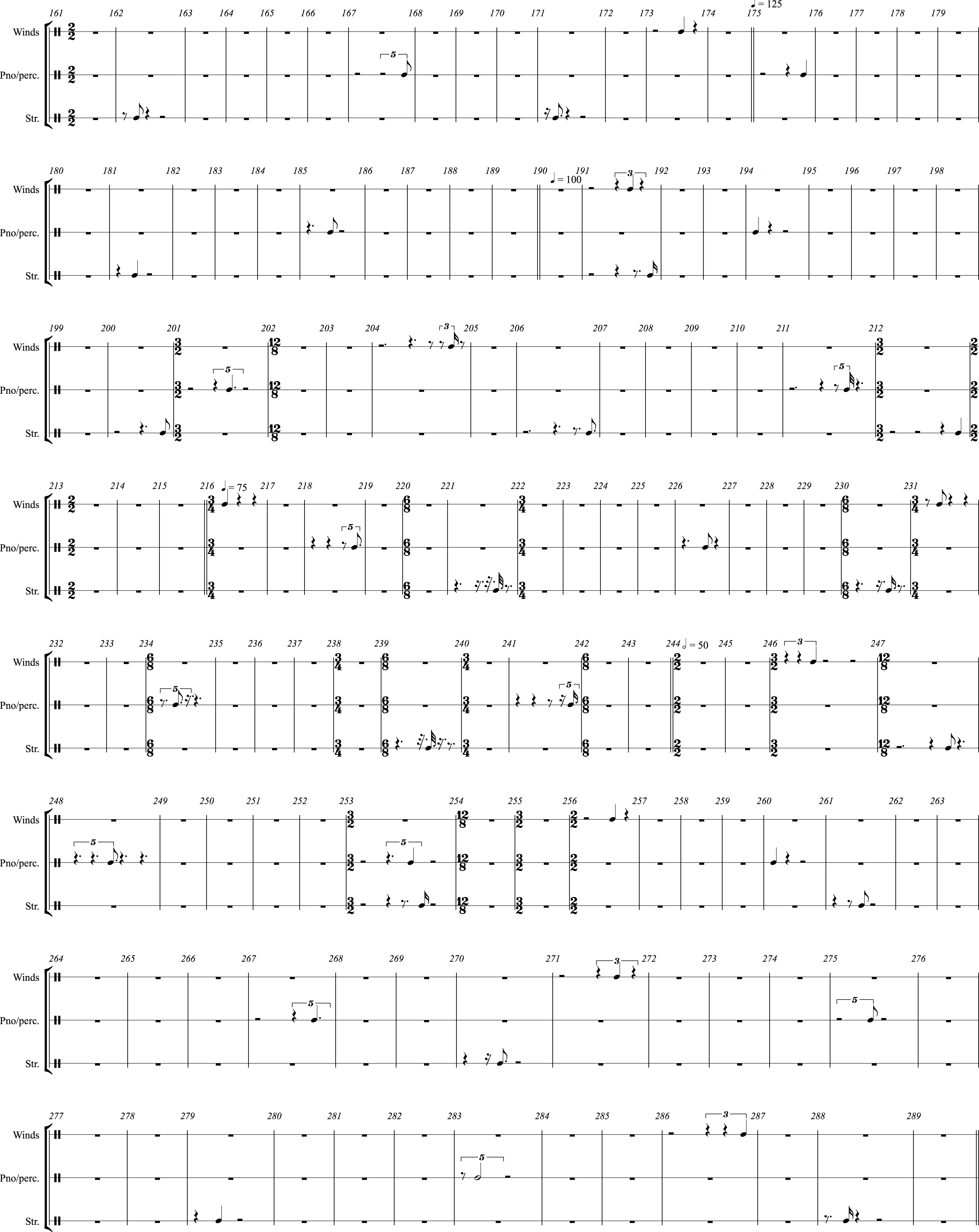

[ 33 ] Example 20 offers a slightly harder edge, in that both attack points represent the initiation of the return of two duos. In the case of the winds, their entrance also represents the debut of two instruments so far not heard in the piece, the piccolo and the bass clarinet. This kind of introduction of new instruments or return to old instruments is found elsewhere as well. When the flute returns in 108, for example, it does so directly on one of its duo’s attack points.

Example 20

Elliott Carter, Triple Duo, mm. 87-90

© Copyright 1994 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

[ 34 ] The passage illustrated in Example 20 initiates a sequence of music in which the winds take on a greater importance in the musical surface. The piano’s entrance at this point, however, is relatively brief, and is of the sort I have indicated as intermittent (int.) on the texture map in Example 13. We now may see that often the presence of an instrument or duo in what seems an intermittent way is occasioned by the need of that duo to articulate an attack point in its limb of the polyrhythm.(12)Link (1994), pp. 66 ff., discusses these pulsations that occur in isolation. This sort of thing may also be seen in Example 14, where the occurrence of a string attack point is marked by the handoff between the instruments, and the flourish in the piano and bass drum instigates the winds’ departure. It is interesting to note that a wind attack point in the same passage is found in the flute, but not marked in any striking way.

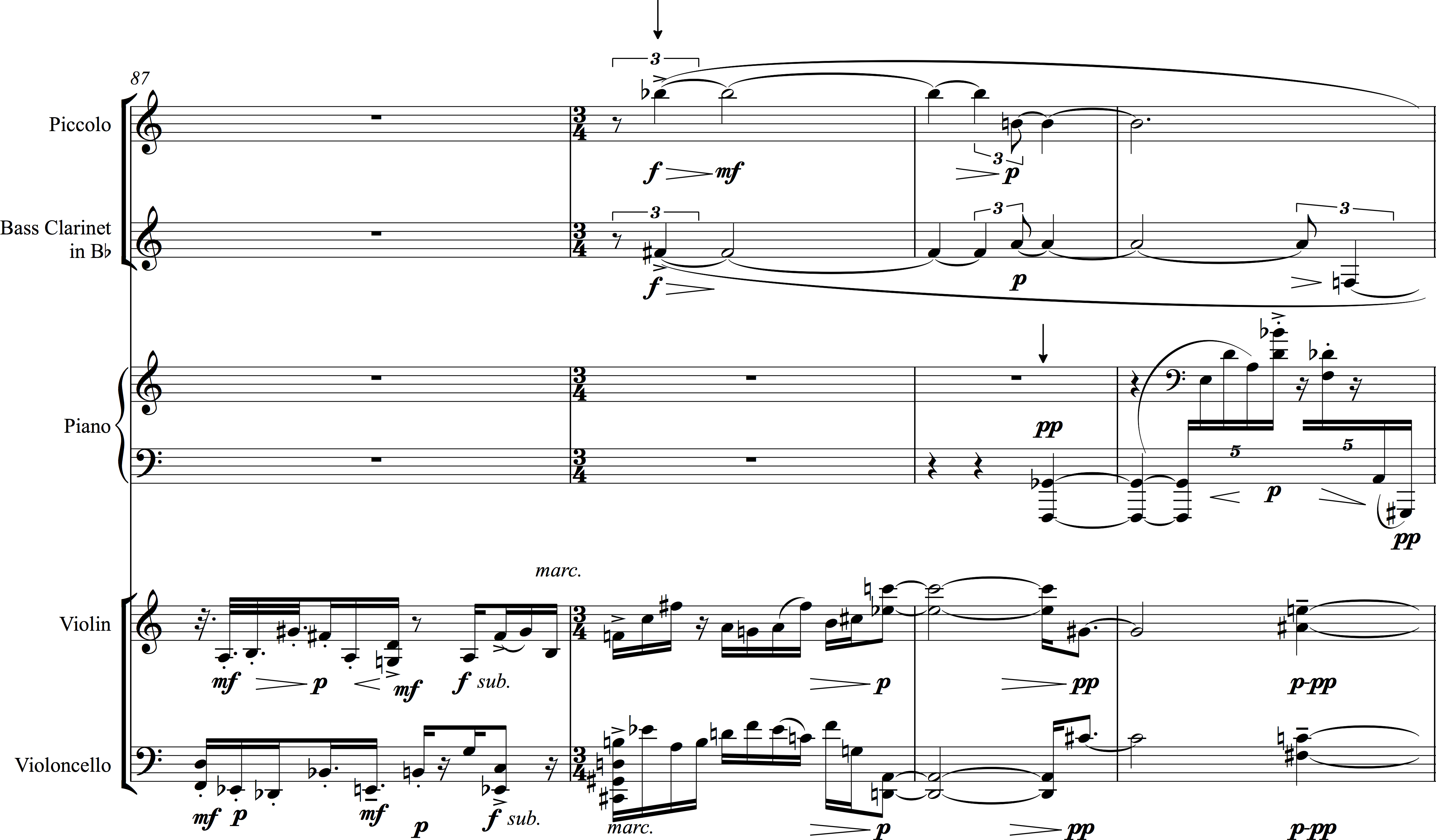

[ 35 ] Example 21 finds two more intermittent moments in a passage otherwise dominated by the winds. Both the cello’s and the piano’s low dyads are occasioned by the underlying polyrhythm, and form a kind of low sonic presence against which we hear the actions of the winds.(13) For accuracy’s sake I should note that the cello’s dyad seems to enter one dotted sixteenth note early, with regard to the abstract polyrhythm. As with the question of the polyrhythm’s curtailment, this would seem to have no impact on the understanding and appreciation of the piece. Example 22 marks another juncture in the texture map, in which the strings initiate a lengthy sustained presence, while the winds depart as the ensemble of primary interest. Here, the winds’ final notes mark their attack point, while the piano in an extremely brief appearance marks one of its duo’s attack points. The strings’ local attack point is found in the cello after the initiation of their music, and does not particularly stand out. Again we are finding a wide variety of uses and articulations for the underlying polyrhythm.

Example 21

Elliott Carter, Triple Duo, mm. 142-150

© Copyright 1994 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

Example 22

Elliott Carter, Triple Duo, mm. 157-162

© Copyright 1994 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

[ 36 ] The foregoing example helps illustrate another use for the polyrhythm in shaping the piece. As noted, many of the intermittent appearances of duos in the music are motivated by that duo’s need to articulate one of its attack points. Doing so helps extend the variety of ways ensembles relate to each other, as rivals, commentators, coequals, accompanists and so on.

[ 37 ] While the polyrhythm attack points are often buried within more detailed rhythmic surfaces, there are occasions in which they are more prominent. We have observed that in some intermittent appearances in previous examples, but Example 23 illustrates a situation in which they clearly articulate the primary gestures heard at the surface. This passage, roughly in the middle of the piece, is a combination of slow, sustained music in all duos. The entrances of both the strings and the winds here articulate their underlying attack points, and similar long notes in the strings both before and after the passage illustrated in the example are similarly articulated. It is at what David Schiff has called the "still center" of the work that the underlying slow pulses that guide so many features of the music may be gently felt, unburdened of further elaboration.(14)Schiff 1998, p. 123.

Example 23

Elliott Carter, Triple Duo, mm. 267-75

© Copyright 1994 by Hendon Music, Inc., a Boosey & Hawkes Company

[ 38 ] The foregoing has not been offered as a complete analysis of any given Carter piece, nor does it attempt to address the technical issues surrounding his rhythmical language. Rather, what I have sought to intimate is the profusion of ways that Carter composes out what might all too easily be imagined as merely mechanical or technical processes. Much of the beauty and intrigue of this music comes from the interaction of certain kinds of regularity with the fancy of the moment. The non-alignment of pattern changes, or the bleeding of one musical character into another, help to create the balance between the spontaneity of the moment with an overall unfolding of the musical argument in these works. The effect is not unlike imagining a patterned tapestry draped across a complex piece of furniture. Both tapestry and table might have certain regularities within them, but their interaction, further shaped by a play of light and shadow, can offer a vision of individuated folds and highlights. The pleasure we might take from contemplating such a tableau emerges from our abilities to discern the various influences of each element. So too it may be with Carter’s music, in which the lively play of character results from varied interaction of his musical constants.

Footnotes

1. See, for example, Schiff 1998, p. 85, Mead 1984, pp. 31-60, and Noubel 2000, pp. 165-71.

2. See Mead 1984 for a discussion of pitch in this work.

3. Schiff 1998; see the discussion on pp. 139-141.

4. Roeder 2012 makes a number of related observations.

5. Schiff 1998, pp. 139-41, both identifies these three musical characters and further connects some of these differences with the title of the work, which refers to contrasting breathing patterns in classical Greek.

6. See Mead 2012 for a detailed discussion of this polyrhythm, and a more general consideration of the issues surrounding constructing long-range polyrhythms using traditional notational constraints. See also Mead 2007.

7. "Limb" refers to a single strand of a polyrhythm, so that a polyrhythm of 25:21 would have two limbs, one of 25 elements (timespans) and one of 21 elements. "Timespan" here, as may be inferred, refers to a single element of the limb of a polyrhythm.

8. See Schiff 1998, pages 148 and 149 for his take on this music. I find myself in disagreement with his analysis of the polyrhythm. For a lengthier discussion of the technicalities of this and other polyrhythms, see Mead 2012.

9. Schiff 1998, p. 149, notes this detail in his discussion.

10. Schiff 1998; see pp. 120-124.

11. See Mead 2007.

12. Link 1994, pp. 66 ff., discusses these pulsations that occur in isolation.

13. For accuracy’s sake I should note that the cello’s dyad seems to enter one dotted sixteenth note early, with regard to the abstract polyrhythm. As with the question of the polyrhythm’s curtailment, this would seem to have no impact on the understanding and appreciation of the piece.

Works Cited

Link, John. 1994. “Long-Range Polyrhythms in Elliott Carter’s Recent Music.” Ph.D. dissertation, City University of New York. www.johnlinkmusic.com/JohnLinkDiss.pdf

Mead, Andrew. 1984. “Pitch Structure in Elliott Carter’s String Quartet #3.” Perspectives of New Music 22: 31-60

_________. 2007. “On Tempo Relations.” Perspectives of New Music 45, no. 1: 64-109.

_________. 2012. “Time Management: Rhythm as a Formal Determinant in Certain Works of Elliott Carter.” In Elliott Carter Studies. Ed. Marguerite Boland and John Link. Cambridge University Press, pp. 138-167.

Noubel, Max. Elliott Carter ou le temps fertile. Geneva: Contrechamps editions, 2000.

Roeder, John. 2012. “’The matter of human cooperation’ in Carter’s Mature Style.” In Elliott Carter Studies. Ed. Marguerite Boland and John Link. Cambridge University Press, pp. 110 – 137.

Schiff, David. 1998. The Music of Elliott Carter. Revised second edn. London: Faber; Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.