Mistaken Identities in Carter’s Variations for Orchestra

Jeff Nichols

Abstract

Composed after the ground-breaking First String Quartet, Elliott Carter’s Variations for Orchestra extends many of the innovations that elevated that work, and Carter himself, to the status of official representatives of the postwar avant-garde. However, the Variations still include many procedures more typical of the quasi-neoclassical style that characterized Carter’s earlier music. This stylistic crux reflects a paradox centered on the nature and presentation of the variations’ main theme: This lengthy (74-note), meandering theme is accompanied and punctuated by materials often more arresting than the theme itself, materials set in motion in the work’s introduction and thereby afforded a kind of perceptual priority that the theme does not strongly challenge. In the course of the variations, many passages seem to take arbitrarily selected elements of musical matter as their basis, suggesting that virtually any event utterable by the orchestra could become referential and thus at least momentarily supersede the theme itself as the primary referent for the work. Other passages present conventional homophonic textures that highlight not the theme, but transformations of secondary materials masquerading as the theme. In constructing variations with such ambiguous materials, Carter seems to offer a disquisition on the nature of the musical idea itself. His interpretation of the genre has the effect of rendering the theme athematic, and non-melodic elements of the texture thematic, in ways that anticipate his more abstract orchestral works of the 1960s, the 1970s and beyond.

[ 1 ] When as a young person steeped in the postwar European avant-garde I first encountered Elliott Carter’s Variations for Orchestra, I found the work’s stylistic heterogeneity very disconcerting. On the one hand, it contained examples of the metric modulation, polyrhythms and exquisitely layered athematic textures reminiscent of later Carter works that I already knew and loved. On the other, it included what seemed to me at the time hackneyed Neoclassical devices, such as traditional motivic development and a harmonic language that, while largely atonal, at times recalled that of mid-century tonal symphonists. The orchestration, although brilliantly colorful, did not seem to me uniformly inventive; I was especially put off by textures like stentorian string lines in octaves, pastoral flowing woodwind figures, fugatos, brass chorales and the like.

[ 2 ] As I came to know this work and its immediate predecessors in Carter’s oeuvre better over the years, I gradually arrived at the view that, far from representing an uneasy and unsuccessful alliance between the disparate stylistic worlds that it evokes, the Variations maximize that stylistic tension in a kind of apotheosis in which the concept of a theme as a readily identifiable entity once and for all – for Carter at least – is replaced by harmonic, timbral, and rhythmic processes that render such explicit referentiality moot. Furthermore, the stylistic disparities I’ve noted, coupled with the work’s historical position as the last piece of Carter’s that invokes a conventional thematicism,(1)For a nuanced discussion of a less explicit mode of thematicism in Carter’s later music, see Arnold Whittall 2012. Whitall argues against seeing “the special features of Carter’s late style... as contradicting all that had gone before” (p. 71) and posits that “it is a useful strategy to think of thematicism (in the traditional sense) as suspended – not eliminated – by the ‘abstract counterbalancing’ of diverse motivic elements – especially if ‘abstract’ can carry with it the idea of ordered materials deriving from unordered materials which imperceptibly control – up to a point – the process and progress of the music” (p. 66). have led me to hear the work almost allegorically as enacting Carter’s farewell to Neoclassicism and his embrace of the modernist ideas that would characterize the rest of his life’s work. I will try in this paper to sketch how this quasi-narrative hearing of the work functions musically and dramatically.(2)David Schiff (Schiff 1998) and Orin Moe (Moe 1982) have offered accounts of this work that inform my observations here. As Moe remarks, the Variations are “the last work of Carter to show an easily recognizable contact with the past and the first to reveal all the essential qualities of his mature style.” (Moe 1982, 11).

[ 3 ] That such a departure was in fact much on Carter’s mind in the forties and fifties is brilliantly documented in an article by Jonathan Bernard, “Elliott Carter and the Modern Meaning of Time” (Bernard 1995Bernard, Jonathan W. 1995. “Elliott Carter and the Modern Meaning of Time,” The Musical Quarterly 79, no. 4: 644-682., 245). In that article Bernard cites the critical influence of the ideas of the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead on Carter’s mature compositional practice and on Carter’s writings on time, particularly those dating from the period of stylistic transition that culminates with the Variations. Carter had discovered Whitehead’s work while an undergraduate at Harvard, and clearly the encounter left him with an intellectual framework that he was able to use decades later in pursuing his own personal extension of the American and European modernist experiments of the first half of the century. Bernard writes:

Whitehead’s “principle of organism” was one of the more important ideas that Carter took away from [his encounter with Whitehead’s work.] This “organism” is not a thing, but rather “a temporally bounded process which organizes a variety of given elements into a new fact.” Such unities, which Whitehead calls “events,” arise from their environment; . . . Whitehead was convinced that “it is a mistake for philosophers to begin with substances which appear solid or obvious to them . . . and then, almost as if it were an afterthought, bring in transient experiences to provide these with an adventitious historical filling. The transient experiences are the ultimate realities” (Bernard 1995Bernard, Jonathan W. 1995. “Elliott Carter and the Modern Meaning of Time,” The Musical Quarterly 79, no. 4: 644-682., 649-650).

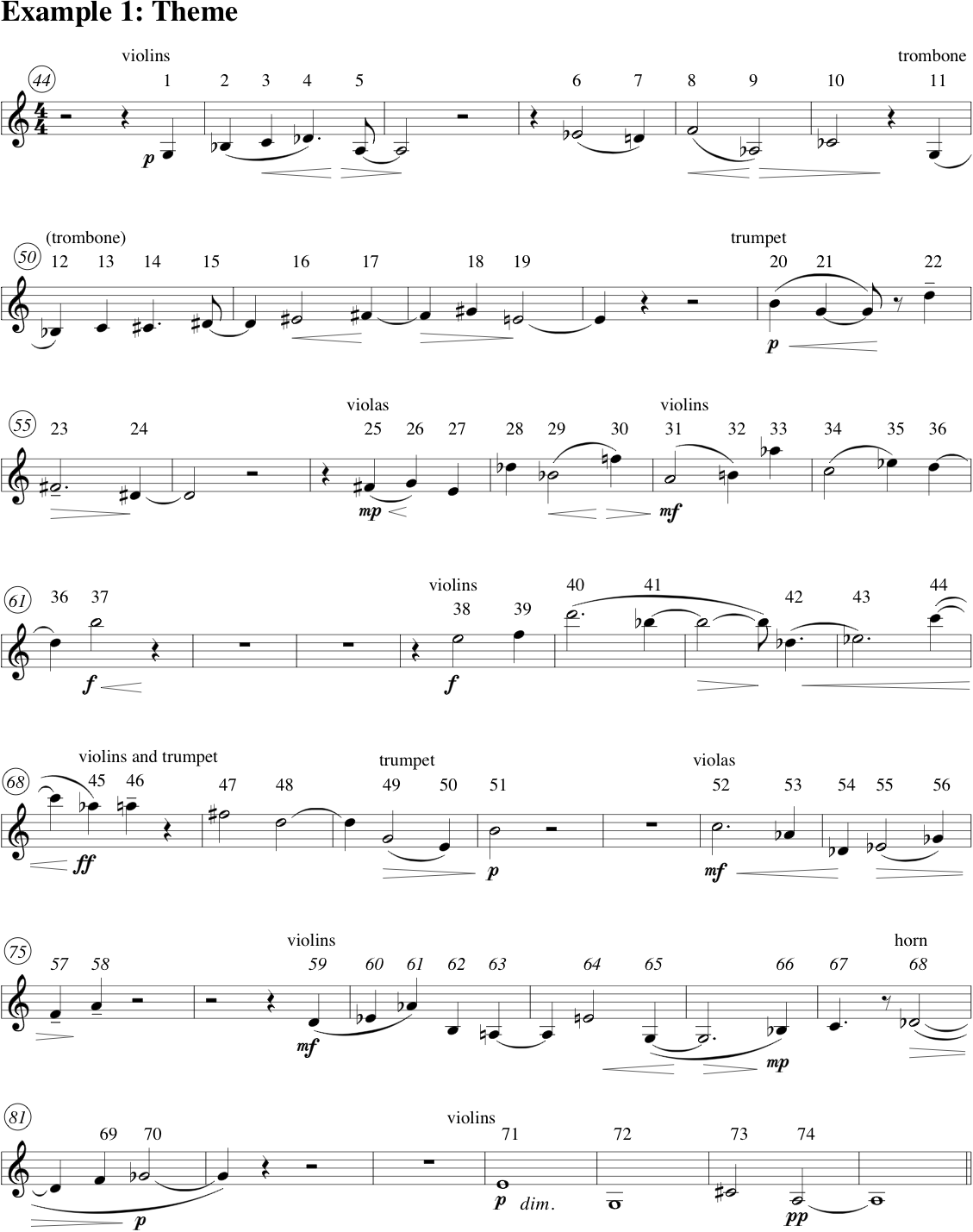

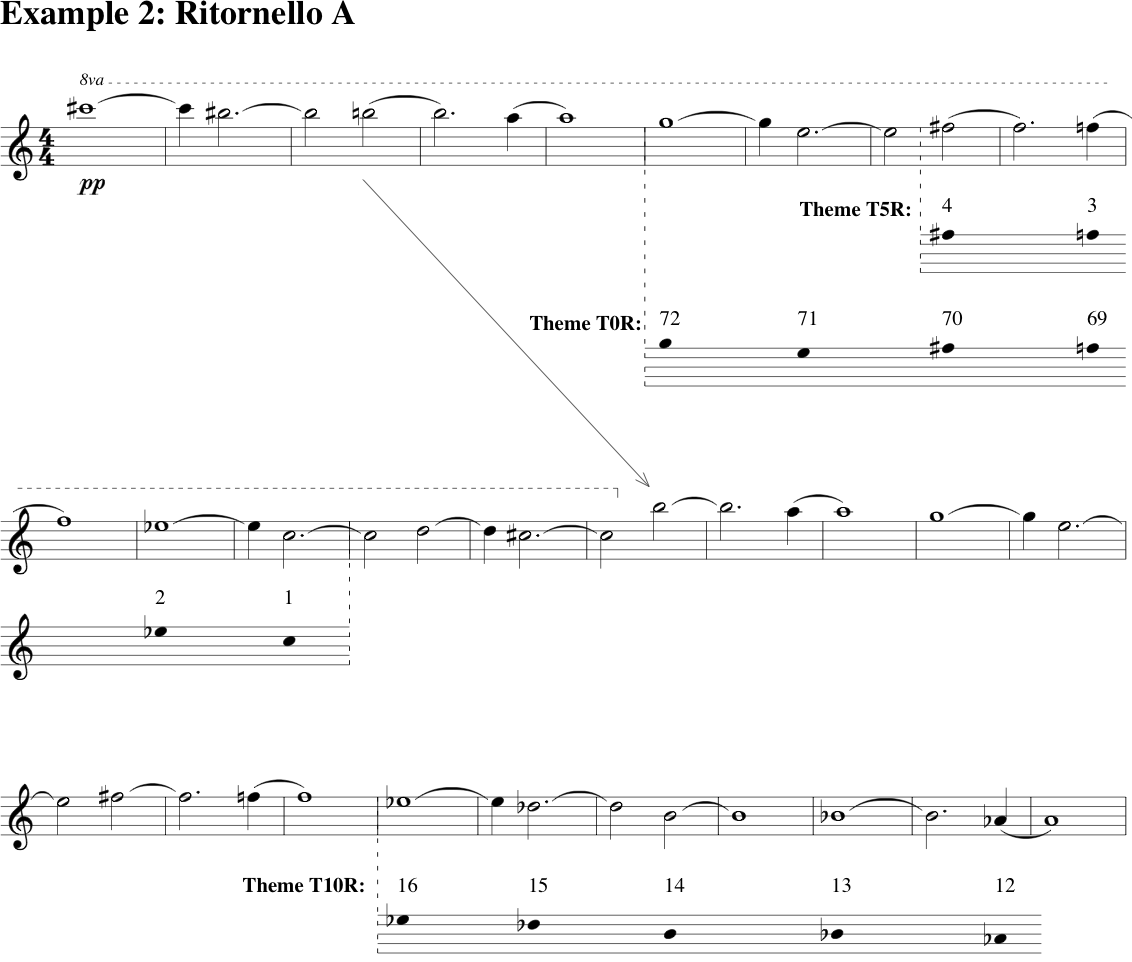

[ 4 ] By means of examples taken from several of the Variations I hope to show how Carter transforms the main theme from a “solid and obvious” object into a source of infinitely mutable and often not clearly identifiable fragmentary transformations. As Carter himself has pointed out, and as many authors have elaborated, the Variations are based not just on a theme, but on three primary ideas: the Theme, shown in Example 1, and two recurring figures shown in Examples 2 and 3 that, following David Schiff (Schiff 1998Schiff, David. 1998. The Music of Elliott Carter. Revised second edn. London: Faber; Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press., 278-290), I will call Ritornello A and Ritornello B.(3)Orin Moe identifies two further primary ideas which he labels simply “chords” and “scherzo rhythm.” The precise enumeration of basic ideas is less important than his observation that much of the work can be viewed as an interplay among “character complexes,” stylistic qualities (like lyricism, scherzo rhythms or chords) abstracted from specific musical events and capable of functioning independently (Moe 1982, 12). Ritornello A accompanies the theme at a very slow tempo, and accelerates each time it appears in the work. Ritornello B forms the climax of the work’s introduction and decelerates with each later iteration. Rather than embellishing the theme in the variations or using it as a primary source of clearly identifiable motives, Carter inverts the priority of primary and secondary layers of the texture, reserving the most explicit references to prior material – that is, the moments that are developmental in the traditional sense – for the ritornelli, while displaying an astonishing range of techniques for disguising the theme’s identity in its later manifestations. The result is that the underlying ideas projected by the evolution of the ritornelli over the course of the whole work – constant and endless acceleration and deceleration – become its unifying ideas, while the relatively few explicit references to the theme gradually acquire either a forlorn or a hyperdramatic aspect, as though lamenting or protesting its increasing irrelevance.

Audio Example 1

Elliott Carter, Variations for Orchestra, mm. 1-52

[ 5 ] These three generative ideas are certainly distinctive enough in their initial appearances. The Ritornelli articulate extremes in several textural dimensions that are mediated by the theme. The rhythms of Ritornelli A and B consist entirely of equal pulses, which in the first case are very slow and in the second very fast. The rhythm of the theme, on the other hand, is built on a clearly maintained, but irregularly grouped, moderate pulse. Orchestrationally, the theme again occupies the middle ground; it features individual choirs from the orchestra, mainly alternating the strings and brass, while Ritornello B is scored as a tutti and Ritornello A is played by two solo violins. The theme’s essentially lyrical character is conveyed by its restriction to a registral span only slightly greater than that of a single voice, while the ritornelli both extend well beyond any vocal range; Ritornello B ascends from very low to very high and Ritornello A descends from very high to very low.

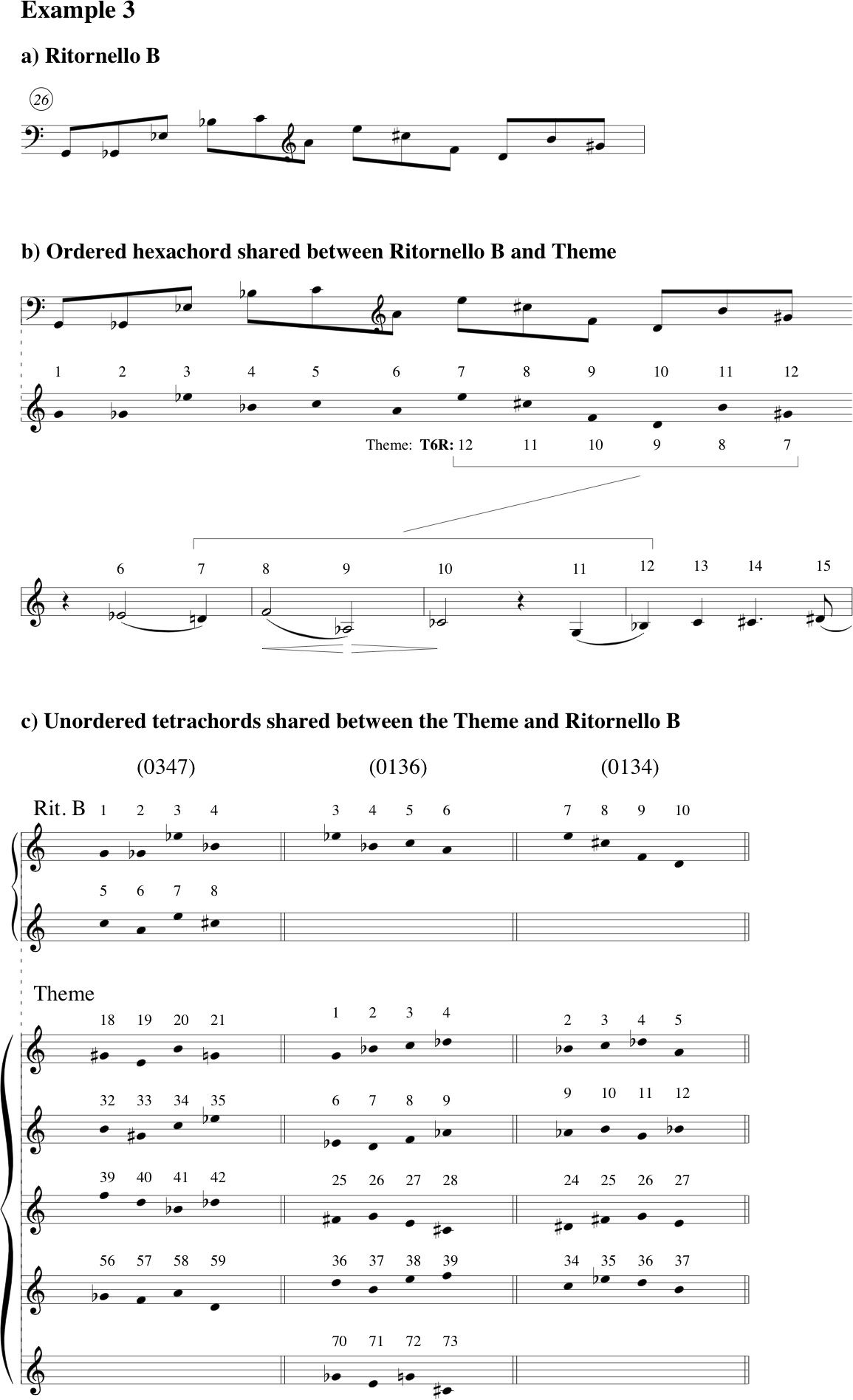

[ 6 ] If these three basic ideas represent starkly differentiated orchestral textures, intervallically the picture is more complicated. The theme and Ritornello B share an emphasis on major and minor thirds (ic 4 and 3), as distinct from Ritornello A’s emphasis on stepwise motion (ic 1 and 2). As shown in Example 3, Ritornello B shares not just intervallic proclivities but several unordered tetrachords and even an ordered six-note segment with the theme. Example 3b shows that the last six notes of Ritornello B are a transposed retrograde of notes 7-12 of the theme. Ritornello A shares fewer collections with the theme, but among them are four-note ordered segments from the beginning and near the end of the theme, as shown in Example 2.

[ 7 ] Moreover, as Example 3c implies, the theme is internally redundant.(4)Moe 1982, Beckstrom 1983 and Schiff 1998 all emphasize this aspect of the theme. See for example Schiff 1998, 280. The example shows which notes of Ritornello B and the theme express the shared tetrachords (0347), (0136) and (0134). David Schiff describes such recurring collections as unifying devices, but at the same time observes that much of the treatment of the theme in the course of the Variations is quasi-serial.(5)Stewart 1973 is an early, brief but telling exploration of serial ordering in the Variations. For an authoritative discussion of twelve-tone structures in later works of Carter, see Mead 1995. This quite accurate description reveals problems of identity built into the very premises of the work. The theme’s referential series of intervals is, first of all, very long – 74 notes in the case of the theme – and second, quite redundant. This means that references to it that retain, in serial fashion, only intervallic sequences and not rhythm, timbre, or often even melodic contour, are particularly difficult to associate with any specific fragment of the theme. The ambiguous intervallic structure is reinforced by the theme’s rhythms, which are vaguely alike from phrase to phrase – steadily flowing quarter and half notes, at times mildly syncopated, but without anything so distinctive as an occasional dotted rhythm, triplet or grace note. My reading of the whole work depends on this comparative lack of clear motivic hooks in the theme. Although at the work’s outset the rhetoric is extremely traditional, with an unstable, agitato introduction followed by a relaxed, flowing theme, the theme’s fuzziness is exploited immediately in the first variation to throw us off any potential trail of clear motivic references. Audio Example 2 presents the final phrases of the theme and the beginning of the first variation (measures 76-98).

Audio Example 2

Elliott Carter, Variations for Orchestra, mm. 76-98

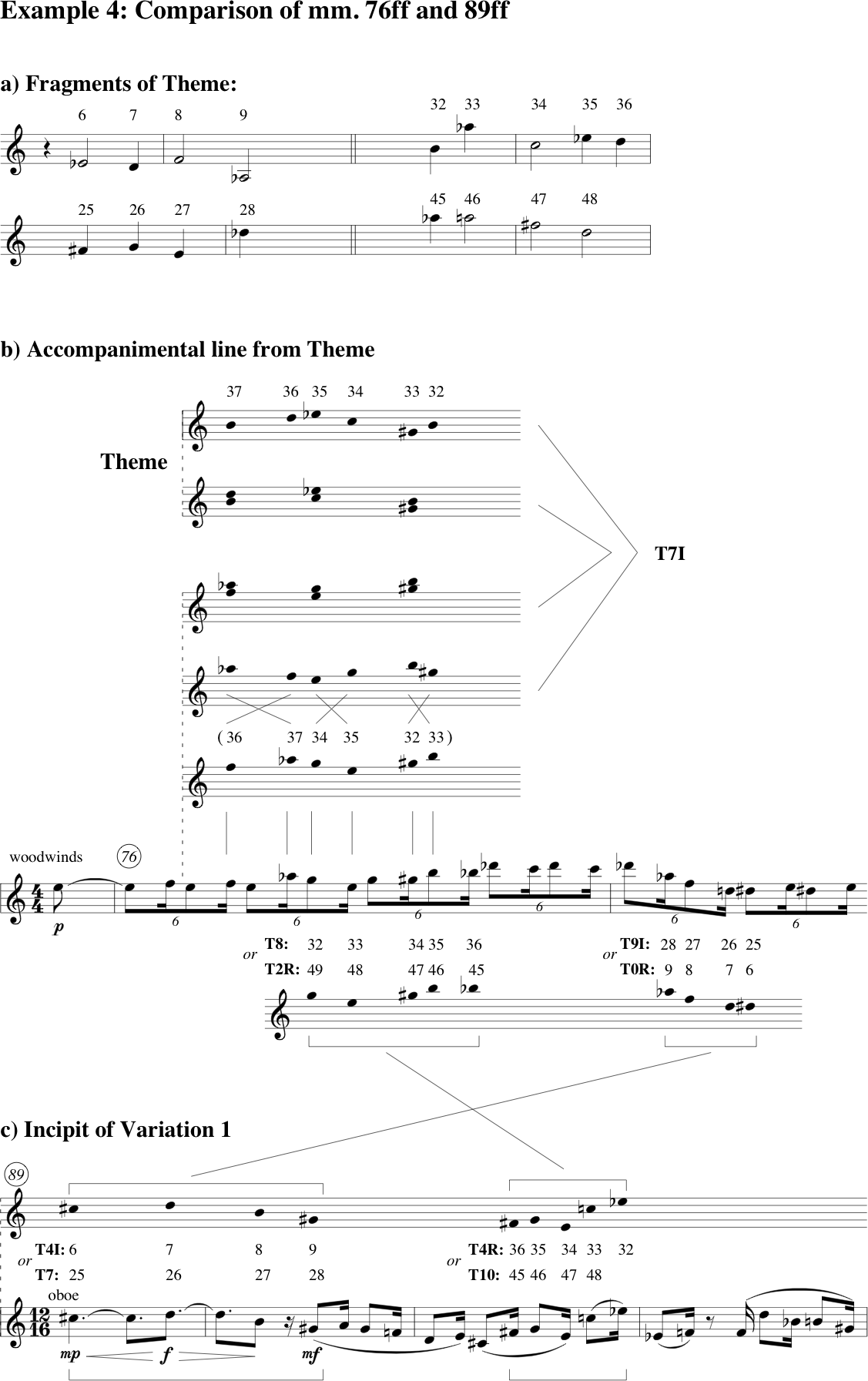

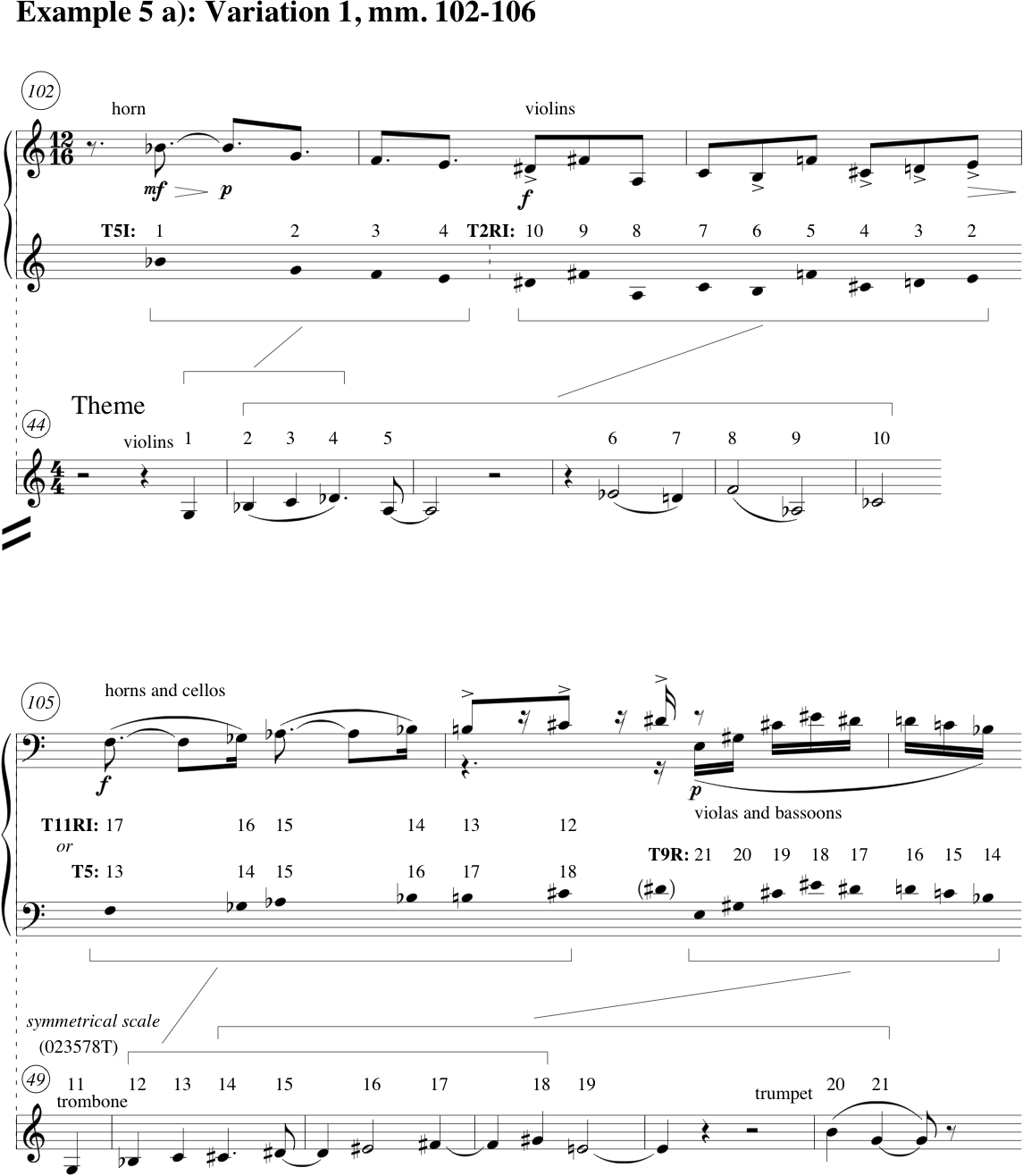

[ 8 ] The first variation begins with a flowing woodwind figure that has been anticipated in an accompanimental line in the theme itself. Example 4 compares the triplet line from the opening of Variation 1 with the first appearance of such figuration in measures 76ff.(6)Since the rhythm referred to here maintains an identity based on triple groupings of sixteenth-notes, I refer to it loosely as “triplets” even though at times the rhythm is notated as sextuplets (as in the woodwinds in mm. 76-78) and at other times in the triple groupings of a compound meter (as in the woodwinds in mm. 89ff.). Both lines contain references to the theme, or successions of notes that echo thematic fragments. But these segments are not particularly emphasized in either line and seem to result from a generalized reliance on similar tetrachords – tetrachords heavily seeded with ic 3 and 4 – rather than from any kind of direct motivic derivation. Certainly the opening of Variation 1 refers to and develops the accompanimental texture of measures 76ff. I want to emphasize this very conventional motivic association because it contrasts so strongly with the treatment of the theme itself in Variation 1. It is not until measure 102 that I at least have been able to identify sustained references to the theme. Beginning in that measure the theme unfolds phrase by phrase, but in extremely altered form (shown in Example 5), alternating inverted and retrograde-inverted segments, and including in measure 105 a fragment that could be read as either a transposition or a retrograde inversion. The texture reflects this instability, as thematic phrases shift between quick, flowing triple rhythms and interruptive slower attacks in harp and solo violins (beginning in m. 109). In the staves below the melodic line I show the basic successions of pitches and how they are related to thematic fragments. Notice that the woodwind triplets from the outset of Variation 1 reappear in this passage. Any sense that this passage is primarily made up of references to the theme is undermined by the stronger impression that these figures are part of a motivic chain originating not in the theme, but in the flowing accompanimental triplets of measures 76ff. The theme sneaks into this texture incognito.

[ 9 ] One of the oddest features of Variation 1 is its interrupted momentum. It seems initially to be based on the classical model of variations as embodying typical figuration patterns. At the outset of Variation 1 one may anticipate a triplet variation, to be followed by another characterized by an equally well-defined and recognizable texture. However, within a few phrases the impetus of the Variation’s opening is interrupted by hesitant gestures that eventually absorb and defuse its energy (mm. 109, 113 and 125).

[ 10 ] I suggest that the music here enacts a process of recognition, or rather of déjà vu – that is, the feeling of recognizing something whose precise identity remains inaccessible to the conscious mind. As the flowing triplet accompanimental figure absorbs more and more elements of the theme itself, the music starts to reflect the theme’s original pace and mood. To the extent that the theme has a signature motive, it is probably the rising series of four notes that opens it. The four-note groups of falling notes in mm. 109ff. are not inversions of the theme’s actual opening, but they do share its minor third (i3) – inverted into a major 6th (i9) – and above all its contour and pace. The surreptitious entrance of the theme in inversion in measure 102 initiates a series of events that gradually unravels the prevailing triplet motion and replaces it with the series of questioning pauses. The uncertainty of these pauses is reinforced by another resonance with earlier events: while their contour and intervallic content echo the theme, the use of harp and solo violins in the descending gestures initiated in m. 109 recalls Ritornello A.

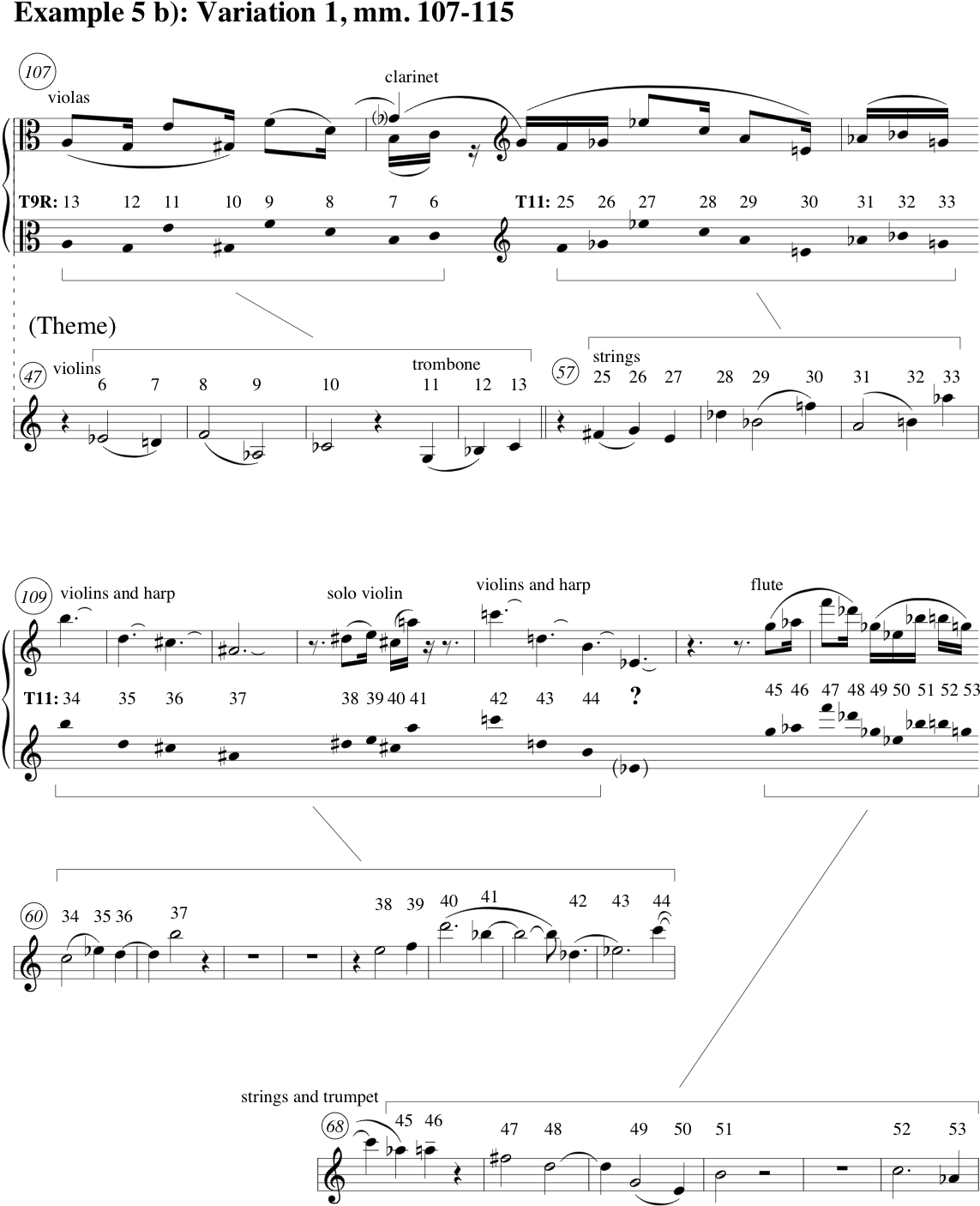

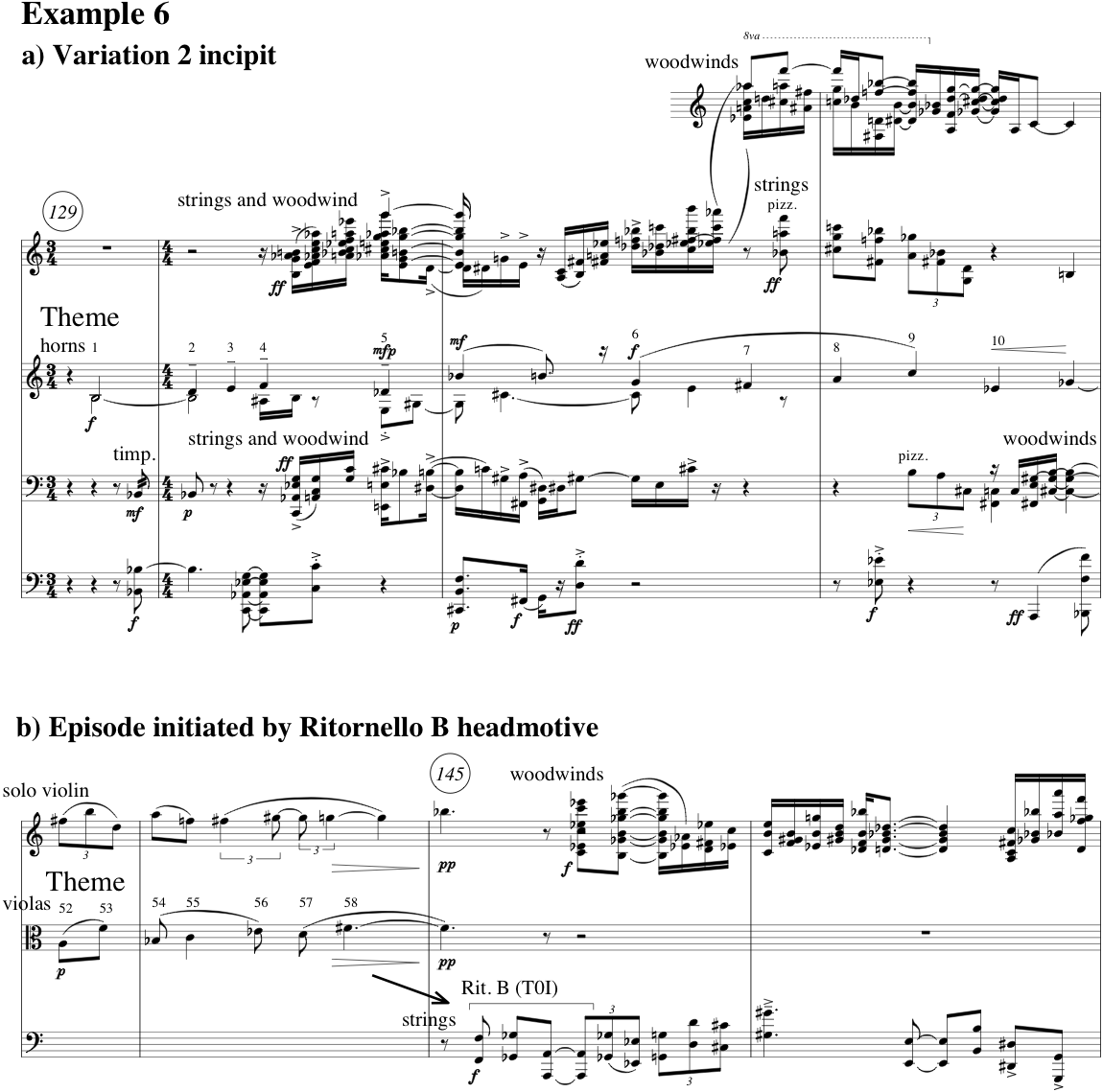

[ 11 ] The first variation, then, seems not so much to elaborate the theme as to consign it to the status of a submerged memory. The second variation functions as a large-scale answer to the questioning first variation, confirming the underground status of the theme, which is now (at least initially) restored to something like its original pace, register, and note sequence, but acts as a cantus firmus buried in an avalanche of other material.(7)“Sounded against [the theme] are imitations at different speeds, which compress or expand the intervals of the theme. These imitations themselves give rise to dense elaborations.” (Schiff 1998, 285). The overall texture at times is so dense that the thematic derivations are largely obscured. Moe describes the material apart from the brass cantus firmus as “fragmentary ideas of Variation 1” (Moe 1982, 17); Beckstrom describes those layers as “very free multiple counterpoint” (Beckstrom 1983, 71). I don’t view these descriptions as mutually exclusive, but rather as indicative of the work’s referential ambiguity. In measures 129-144, the phrases of the theme unfold in order, occasionally peering through masses of angular counterpoint and sweeping woodwind figures but for the most part decidedly secondary to other layers of the texture. (The beginning of this passage is shown in Example 6a.) In measures 145-158 this measured progression is interrupted by an episode initiated by a motive that clearly refers to Ritornello B (See Example 6b) and based solely on the elaborative layers of the texture. (The theme resumes in m. 159 in the piccolo, where it functions as obbligato counterpoint to a statement of Ritornello A in the violins). However, the listener is unlikely to notice the temporary withdrawal of the theme in measures 145-158, because the focus throughout has been on the faster, more aggressive layers of figuration that here dominate to the exclusion of the theme – a kind of hypertrophied expression of the tendency already present in the original presentation of the theme to surround it with more arresting material.

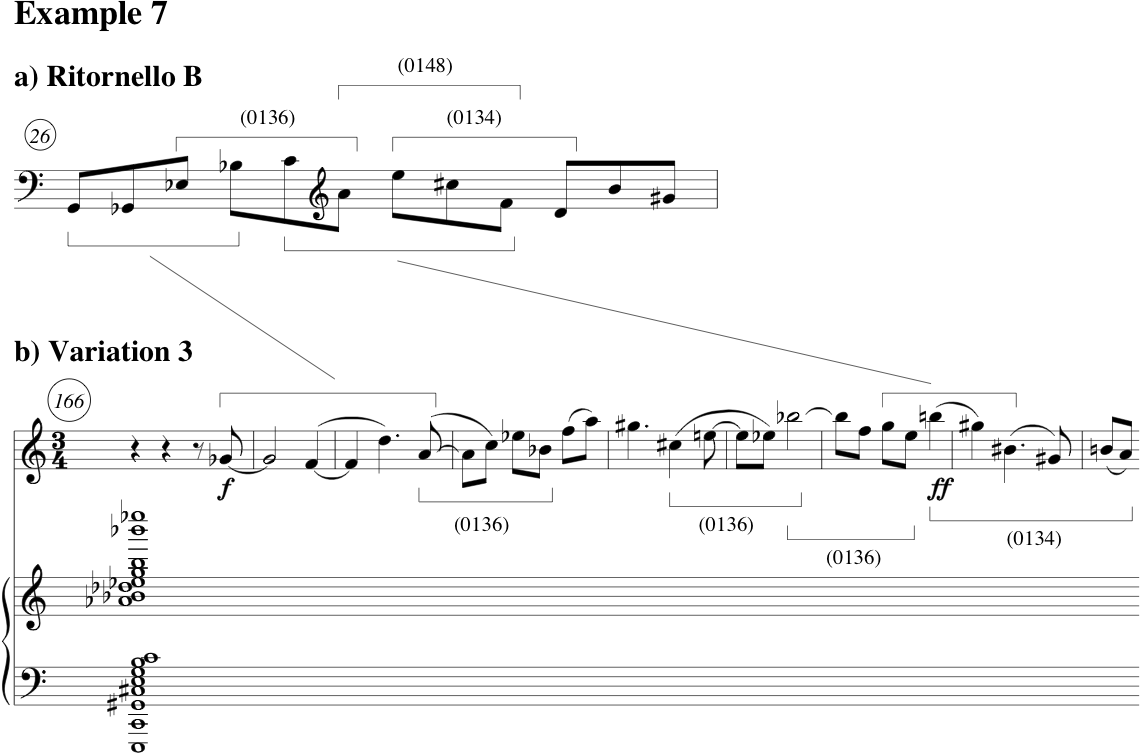

[ 12 ] If Variation 1 dismembers the theme and estranges the resulting fragments from their original context, associating them with an accompanimental layer of the original texture (the triplet motive), and Variation 2 buries the theme with elaborative material, then the outset of Variation 3 (shown in Example 7b reduced to three staves) promises unambiguously to restore its shattered identity. The smoke of Variation 2 clears and we have the simplest texture in the work so far: a single line in the violins with a sustained chord in the rest of the orchestra. Rhetorically this seems a moment of recovered orientation. However, despite the evocation of the original orchestral context of the theme, reproducing its slightly irregular rhythms based on a moderato pulse in the violins, the actual intervallic sequence (as shown in Example 7) bears a stronger resemblance to Ritornello B than to the theme, with the first two ordered tetrachords of Ritornello B and numerous unordered tetrachords reappearing in this melodic line.

[ 13 ] By invoking the pitch structure of Ritornello B in a context otherwise so clearly reminiscent of the theme, the tension between the expected identity of this motive as derived from the theme and its actual instantiation of Ritornello B is maximized. What is the function of this tension in the work?

[ 14 ] Consider the Variations to this point: in them we hear the gradual subsumption of the theme and everything it represents – a stable, unvarying pace; lyricism; and above all a potentially stable point of reference – into the orbit of a motive, Ritornello B, whose most essential characteristic is its decelerating speed with each reiteration. The thematicism of Carter’s middle-period works is being absorbed into a new language before our ears – one in which the idea even of a stable, unified ensemble pulse, much less of a referential motive, is disappearing. But the Variations do not simply occupy this new territory; they enter it step by step. And the first step is to call into question the possibility of secure reference to anything at all.

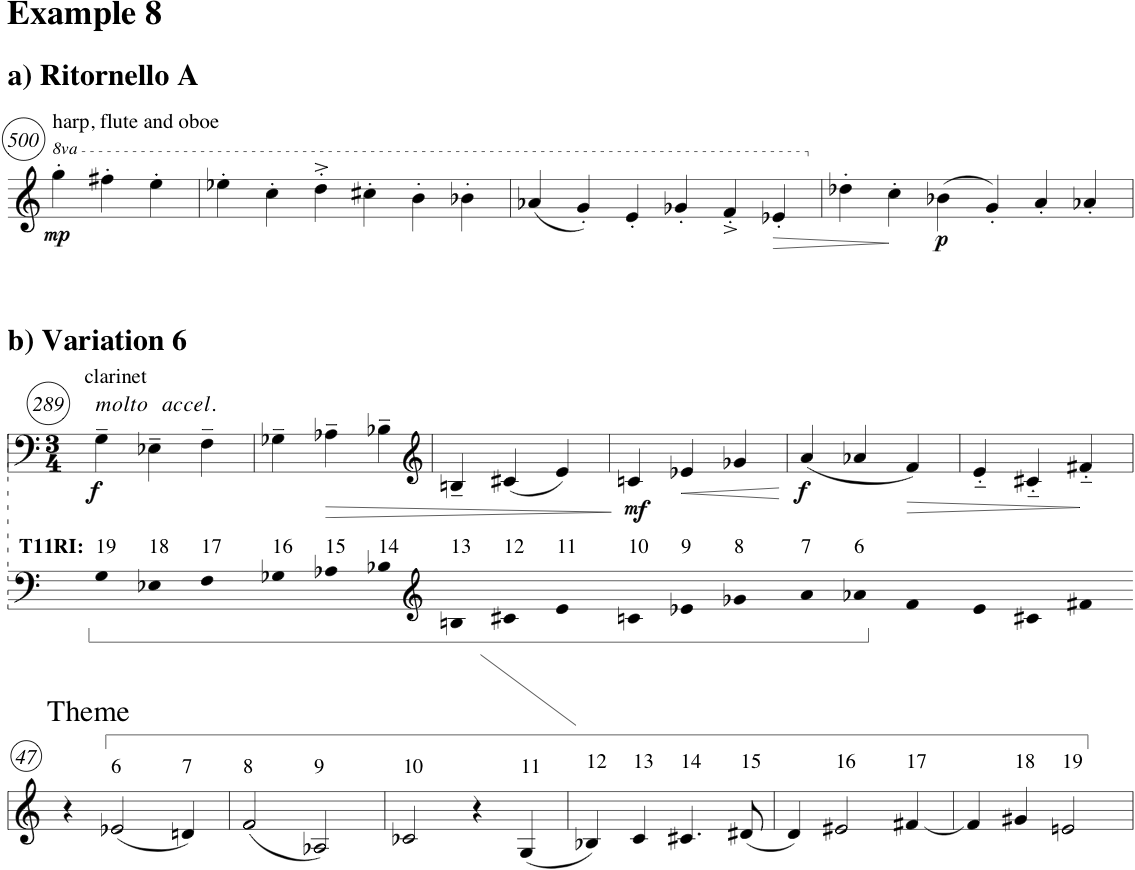

[ 15 ] That this is a disorienting stage in the process is reflected by the woozy obbligato viola line that initiates Variation 4. In this variation, the theme is represented in the thematic fragments that emerge in the oboe, which begin on note 70 of the theme and proceed in retrograde inversion. The central device of this celebrated variation is its chain of ritardandi, with each four-bar phrase intersecting the next at half tempo, suggesting a potentially infinite regression. This is balanced in Variation 6 by a similarly overlapping endless accelerando. As shown in Example 8b, the thematic fragment that initiates Variation 6 would again be almost impossible to associate with its origin in the theme, and instead is likely because of affinities in rhythm, contour and articulation to be heard as anticipating such later statements of Ritornello A as that shown in Example 8a.

[ 16 ] Through these few examples drawn from the first half of the work I hope to have given an idea of what I see as the central dialectic of the Variations: the systematic undermining of the theme’s role as explicitly referential and its replacement in this function by the two ritornelli, which ultimately embed all the work’s material in constantly shifting time scales.(8)Most studies of the Variations treat variations 7-9 as dominated by “subsidiary ideas,” as Orin Moe describes them (Moe 1982, 12). He claims that “the actual notes of the theme do not appear until the finale” (Moe 1982, 18). Moe however anticipates Whittall’s concept of late-modernist thematicism when despite the thematic absence he identifies a kind of recapitulatory quality in these variations: “The lyrical line is sustained from variation 7 through variation 9, with fragments from the first ritornello and the scherzo rhythm played off against it... One musical character, that of lyricism, has been allowed to dominate this set of variations, the longest period given to any expressive quality in the work. Since lyricism is a dominant aspect of the theme, these variations represent, in a way, a return of its spirit” (Moe 1982, 18). This view is consonant with others’, including Whittall’s, idea of the subsumption of concrete musical reference into a dialectic of musical characters that transcend the musical figure, motive or theme.

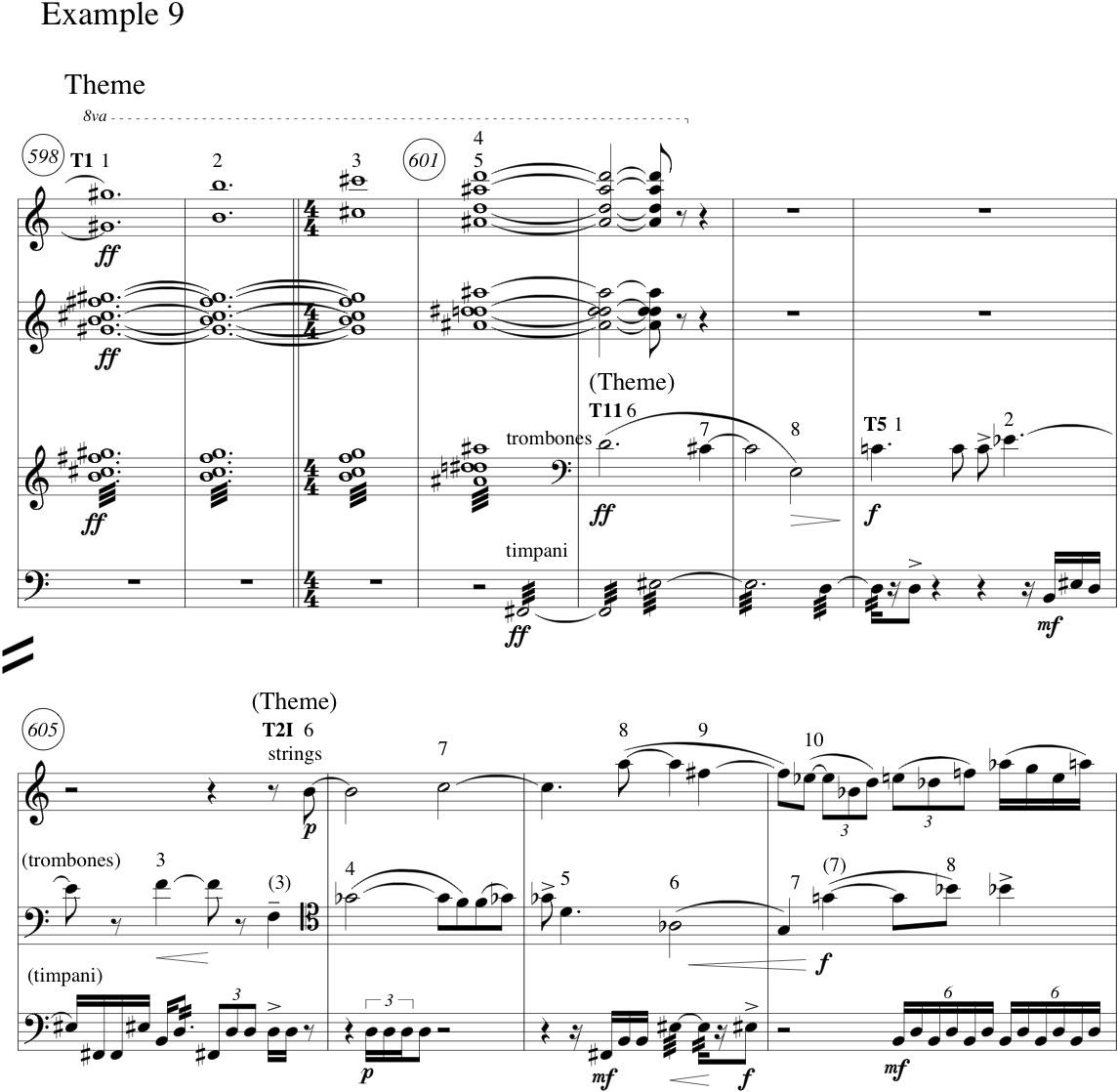

[ 17 ] The dramatic implications and the ultimate basis of my allegorical reading of the whole work will become apparent in a brief discussion of its ending. The finale (so designated by Carter, encompassing measures 470-639) reaches a climax in mm. 597-602 when the head motive of the theme reemerges in its most explicit statement since its original presentation (Example 9). This moment verges on the rhetoric of a Beethovenian triumphalism, but it is a hollow rhetoric and is dispelled on the fourth note of the theme by the dissonant chord that appears there (m. 601). What follows is a passage in which the theme is presented again, this time in an anguished recitative in the trombones, with apocalyptic interjections from the timpani, an extended statement that completely negates the overweening sense of conquest projected by the aborted return of the theme in measures 598-602. (Mm. 579 – 611 are presented in Sound Example 3.)

Audio Example 3

Elliott Carter, Variations for Orchestra, mm. 579-611

[ 18 ] The final evocation of the theme, following the desperate imprecations of the trombones and timpani, is in a completely contrasting mood. In measures 623-626 the last four notes of the theme appear in the violins and violas, clearly audible and unadorned, in what affects me as a profoundly nostalgic gesture. It is too late for the theme to resume the clarity, centrality or frankly robust lyricism of its first presentation. I hear this gesture as one of renunciation, a farewell to a lost world. It is surrounded by the slowest iteration yet of Ritornello B, beginning in the tuba in measure 623, and the fastest of Ritornello A, appearing in the woodwinds in measure 633. In this ending, the wrenching contradictions of the finale’s preceding assertions of the theme (the exaggeratedly buoyant climax undermined by the trombone’s tortured recitative) seem to be resolved as the theme’s last vestiges, and with them all it represents (lyricism and a human scale), give way to Ritornelli A and B, whose sweeping descents and ascents, accelerations and decelerations, are arrows pointing to the infinitely receding limits of space and time. The Romantic subject and the very foundations of music as Carter inherited it – motivic identity and the metric organization of rhythm – are, for Carter at least, permanently displaced by the hierarchy-free webs of mutual reference so characteristic of the postwar avant-garde.

Footnotes

1. For a nuanced discussion of a less explicit mode of thematicism in Carter’s later music, see Arnold Whittall 2012. Whitall argues against seeing “the special features of Carter’s late style... as contradicting all that had gone before” (p. 71) and posits that “it is a useful strategy to think of thematicism (in the traditional sense) as suspended – not eliminated – by the ‘abstract counterbalancing’ of diverse motivic elements – especially if ‘abstract’ can carry with it the idea of ordered materials deriving from unordered materials which imperceptibly control – up to a point – the process and progress of the music” (p. 66).

2. David Schiff (Schiff 1998) and Orin Moe (Moe 1982) have offered accounts of this work that inform my observations here. As Moe remarks, the Variations are “the last work of Carter to show an easily recognizable contact with the past and the first to reveal all the essential qualities of his mature style” (Moe 1982, 11).

3. Orin Moe identifies two further primary ideas which he labels simply “chords” and “scherzo rhythm.” The precise enumeration of basic ideas is less important than his observation that much of the work can be viewed as an interplay among “character complexes,” stylistic qualities (like lyricism, scherzo rhythms or chords) abstracted from specific musical events and capable of functioning independently (Moe 1982, 12).

4. Moe 1982, Beckstrom 1983 and Schiff 1998 all emphasize this aspect of the theme. See for example Schiff 1998, 280.

5. Stewart 1973 is an early, brief, but telling exploration of serial ordering in the Variations. For an authoritative discussion of twelve-tone structures in later works of Carter, see Mead 1995.

6. Since the rhythm referred to here maintains an identity based on triple groupings of sixteenth-notes, I refer to it loosely as “triplets” even though at times the rhythm is notated as sextuplets (as in the woodwinds in mm. 76-78) and at other times in the triple groupings of a compound meter (as in the woodwinds in mm. 89ff.).

7. “Sounded against [the theme] are imitations at different speeds, which compress or expand the intervals of the theme. These imitations themselves give rise to dense elaborations” (Schiff 1998, 285). The overall texture at times is so dense that the thematic derivations are largely obscured. Moe describes the material apart from the brass cantus firmus as “fragmentary ideas of Variation 1” (Moe 1982, 17); Beckstrom describes those layers as “very free multiple counterpoint” (Beckstrom 1983, 71). I don’t view these descriptions as mutually exclusive, but rather as indicative of the work’s referential ambiguity.

8. Most studies of the Variations treat variations 7-9 as dominated by “subsidiary ideas,” as Orin Moe describes them (Moe 1982, 12). He claims that “the actual notes of the theme do not appear until the finale” (Moe 1982, 18). Moe however anticipates Whittall’s concept of late-modernist thematicism when despite the thematic absence he identifies a kind of recapitulatory quality in these variations: “The lyrical line is sustained from variation 7 through variation 9, with fragments from the first ritornello and the scherzo rhythm played off against it. . . . One musical character, that of lyricism, has been allowed to dominate this set of variations, the longest period given to any expressive quality in the work. Since lyricism is a dominant aspect of the theme, these variations represent, in a way, a return of its spirit” (Moe 1982, 18). This view is consonant with others’, including Whittall’s, idea of the subsumption of concrete musical reference into a dialectic of musical characters that transcend the musical figure, motive or theme.

Works Cited

Beckstrom, Robert Allen. 1983. “An Analysis of Elliott Carter’s Variations for Orchestra (1955).” Vol. 1 of Ph.D. diss., University of California at Los Angeles.

Bernard, Jonathan W. 1995. “Elliott Carter and the Modern Meaning of Time.” The Musical Quarterly 79, no. 4: 644-682.

Mead, Andrew. 1995. “Twelve-Tone Composition and the Music of Elliott Carter.” In Concert Music, Rock, and Jazz since 1945; Essays and Analytical Studies. Ed. Elizabeth West Marvin and Richard Hermann. Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Moe, Orin. 1982. “The Music of Elliott Carter.” College Music Symposium 22, no. 1: 7-31.

Schiff, David. 1998. The Music of Elliott Carter. Revised second edn. London: Faber; Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Stewart, Robert. 1973. “Serial Aspects of Elliott Carter’s Variations for Orchestra.” Music Review 34, no. 1: 62-65.

Whittall, Arnold. 2012. “The search for order: Carter’s Symphonia and late-modern thematicism.” In Elliott Carter Studies. Ed. Marguerite Boland and John Link. Cambridge University Press, pp. 57-79.